A few weeks ago, I was out shopping in SoHo when I was gripped by the sensation that everything was about to go horribly wrong. I am not a stranger to such feelings, so I did what I normally do in such circumstances. I leapt to a pet explanation.

“There must be something in my life that I’m worried about but haven’t dealt with.” I sat down on the therapy couch in my mind.

“Maybe it’s just my shopping alarm going off?” I usually have about an hour where I can shop with enthusiasm, but after that some kind of internal alarm goes off and I start to get irritable. But no, it was too strong an emotion to be my shopping alarm.

That’s when the montage of potential issues started rolling faster.

“Work?” No, things were actually pretty good.

“Something in my relationships?” Nope.

“Maybe something to do with family?” Well, there’s always something going on with family but nothing unusual.

With no revelations at hand, I retreated to my apartment, ate an orange, and prepared to take a nap. My kingdom for naps and oranges.

As I drifted off to sleep, I attempted to assuage my rising anxiety. It had been a good week. I was productive, my inbox was clean, and my energy levels seemed higher than usual courtesy of a low carb diet I'd just started. Still, I couldn't help but wonder: What part of my psyche had pressed the panic button and why?

The next day I found a plausible answer in an unexpected place, my friend’s muffin-filled mouth.

“I thought I was going crazy,” I told him as we sat at coffee together.

“That sounds rough,” he said, offering a piece of his breakfast as consolation.

I waved him off. “I’m trying to go low carb,” I said. I showed him the continuous glucose monitor I’d been wearing to help me track my blood sugar levels.

“How long ago did you cut out carbs?” he asked.

“A little over a week,” I said.

“Sounds like carb flu,” he said. “It’s what happens when you cut out carbs completely. You’re not going crazy. It’s a form of withdrawal from sugar.”

“Oh.”

. . .

Everyone has pet explanations.

When we find a model of the world that works, we are tempted to apply it to every situation that comes up. Pet explanations make life simpler, and more understandable. They can make us feel more in control, and better equipped to handle our own lives. But, very often, they are wrong.

In the case of my aborted shopping spree my pet explanation for my sense of dread was, “Every emotion must have some kind of psychological cause.” Though that explanation has often been true, it wasn’t that day. The right explanation turned out to be physiological. My emotions were out of whack, but the real culprit was lack of carbs.

The complicated reality is that what produces a feeling or behavior in me at one time is not necessarily what produces it another time. I might be focused today because I’m on a tight deadline, and I might be focused tomorrow because I turned off notifications on my phone, or because I’m feeling deeply connected to the importance of my work, or because I tried a new productivity hack

But regardless of the cause, I’m tempted to return to a pet explanation to explain what I’m experiencing. The funny thing about pet explanations is that they’re all probably right about certain things, for certain people, in certain situations. The place where they get into trouble is that they can sometimes blind us to what’s actually going on. (And they become memes—more about signaling in-group status than understanding the world.)

So why do we even keep using pet explanations in the first place? Why can’t we just figure out what’s actually going on?

It turns out it’s complicated.

. . .

In the book Behave, neuroendocrinologist and all-around Superorganizers Patron Saint, Robert Sapolsky attempts to explain why humans behave the way they do. Why are we sometimes violent? Why are we sometimes generous?

In order to understand a behavior, Sapolsky argues that we have to understand the interconnected systems that give rise to it. We humans have many interacting systems.

First, there’s the immediate environment, which is stimulating your nervous system. Second, there’s the internal condition of your nervous system itself—whether it’s in a heightened state of alertness, or in soporific slumber. Third, there’s the environment you’ve been in over the last several hours and days, which has primed your endocrine system and created a context in your brain that makes particular behaviors more likely. Fourth, there’s the way your childhood has shaped your brain, and body which dictates how your endocrine system operates and what features of the environment might trigger reactions in you. But it doesn’t stop there. This goes on and on forever. Totally unpacking the causal chain of a behavior requires a trip through the rise and fall of civilizations, through the evolution of human consciousness, and toward the beginning of the universe.

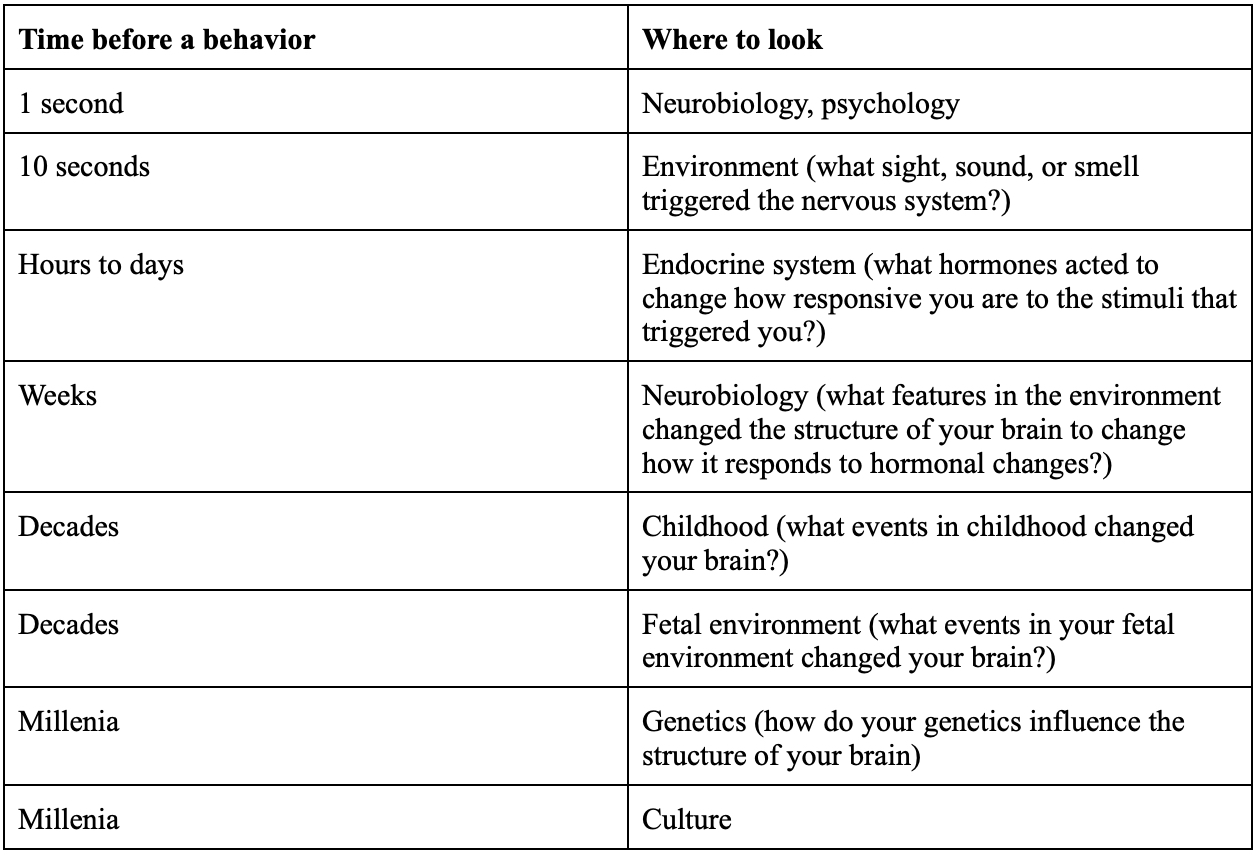

Sapolsky helps us understand this by putting every factor that gives rise to a behavior on a timeline that looks something like this:

This list is obviously non-exhaustive, but it should give you some sense of how complicated things get when you try to explain your own behavior.The key thing to understand is that all of these explanations are linked. They are contained within one another like Matryoshka dolls. If you invoke psychology to explain a behavior you’re explicitly invoking neurobiology, and evolution, and genetics, and the science of fetal development.

This all indicates why pet explanations are necessary. We need to untangle the world from itself, to slice the causal chain up into manageable chunks so that we can understand and predict it. Pet explanations are really just pattern recognition.

This can be extraordinarily useful when we face a new situation that is similar to ones we’ve faced in the past. Unfortunately, pattern-derived thinking makes fools of us when we’re facing situations we’ve never faced before. And, just like what happened to me on my bad day in SoHo, it’s often hard to know whether what we’re facing is familiar—or just seems familiar on the surface.

So what do we do when our pet explanations fail?

. . .

When our pet explanations can’t account for what’s happening to us, the best thing to do is to learn how to expand our search of the explanation space.

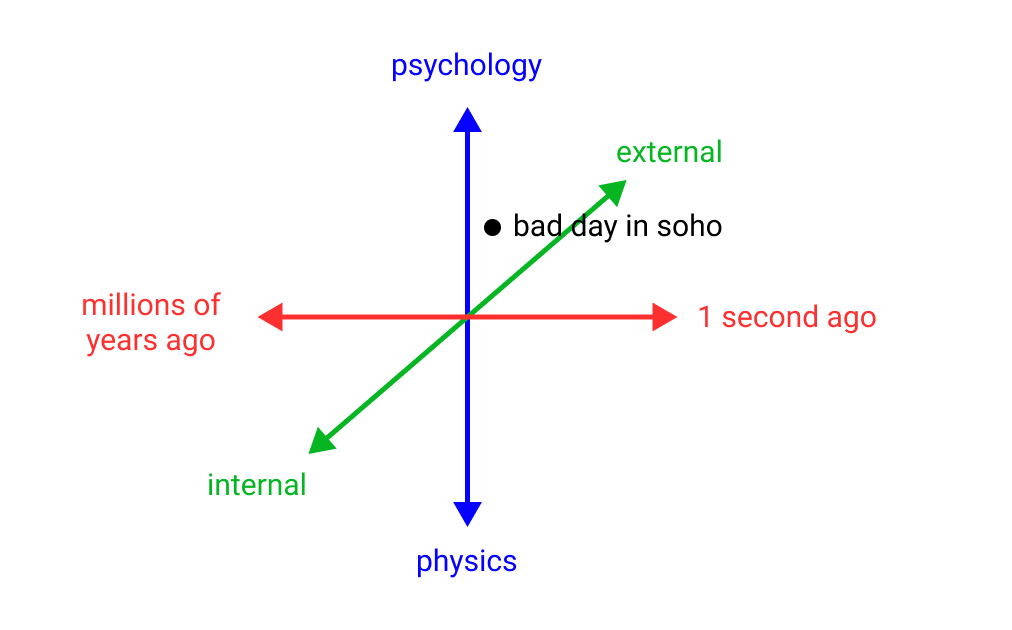

We can do this by mapping it along a few common axes like time, or internal cause vs. external cause, and then deliberately move around on each axis to generate new explanations. When we do this we’ll begin to see how our explanations usually bias our idea of what’s going on, and where broadening them might help.

For example, when I was thinking about why I was feeling so anxious in SoHo my explanation was, “There must be something in my life that I’m worried about but haven’t dealt with.”

This explanation is from a short time ago, and it’s external. It’s mind-focused rather than body focused. And I expressed my explanation at a high level—in terms of qualitative descriptions and psychology—instead of at a low level like biology or neuroscience.

If we plotted it out on a graph it might look something like this:

I wasn’t wrong about everything, but I was in the wrong quadrant of the graph. What I missed was that if I flipped my mind-focused explanation to a body-focused one, I would’ve been able to more skillfully navigate the situation that I found myself in.

Seeing things on a graph this way helps us see how much space there is to look for different explanations—and how little of it we actually use.

Now, I’m not advocating that anyone should graph things out like this in real-time. But it can be a useful exercise to do on yourself if you find that you’re consistently having trouble with problems that come up in your life related to productivity and emotional state.

Here are some questions that might help you get started:

Are your explanations usually from a short time ago or a long time ago?

Are your explanations usually internal or external?

If your explanations are internal, are they usually about the mind or the body?

At what levels of abstraction can you express your explanations? Low-level or high-level?

But these are just starter questions. There are infinitely many axes to experiment with—and the point is to broaden your search space until you find something that works for you.

. . .

Here’s the key lesson from my bad day in New York: What we want to do is learn to cultivate flexibility. We want to be able to see the interconnected nature of all of our experience, and to know where our explanations for that experience tend to cluster.

It also helps to notice when those pet explanations aren’t working, and have the courage to look underneath them. If we do that we can broaden what we’re willing to experiment with in order to better understand and move through our lives.

When we find only explanations that conform to our experience, we cease to acknowledge that things change. Our psychology changes. Our bodies change. Our circumstances change. Sometimes we are aware of those changes and sometimes we are not. What epistemic humility does is release us from pet explanations, granting us access to a broader selection of ideas and behavior.

It grants us the freedom to experiment in service of seeing what works.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!