.28.41_AM.png)

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Before I opened my laptop, the code had reviewed itself.

I launched GitHub expecting to dive into my usual routine—flag poorly named variables, trim excessive tests, and suggest simpler ways to handle errors. Instead, I found a few strong comments from Claude Code, the AI that writes and edits in my terminal:

"Changed variable naming to match pattern from PR [pull request] #234, removed excessive test coverage per feedback on PR #219, added error handling similar to approved approach in PR #241."

In other words, Claude had learned from three prior months of code reviews and applied those lessons without being asked. It had picked up my tastes thoroughly, the way a sharp new teammate would—and with receipts.

It felt like cheating, but it wasn't—it was compounding. Every time we fix something, the system learns. Every time we review something, the system learns. Every time we fail in an avoidable way, the system learns. That's how we build Cora, Every’s AI-enabled email assistant, now: Create systems that create systems, then get out of the way.

I call this compounding engineering: building self-improving development systems where each iteration makes the next one faster, safer, and better.

Typical AI engineering is about short-term gains. You prompt, it codes, you ship. Then you start over. Compounding engineering is about building systems with memory, where every pull request teaches the system, every bug becomes a permanent lesson, and every code review updates the defaults. AI engineering makes you faster today. Compounding engineering makes you faster tomorrow, and each day after.

Three months of compounding engineering on Cora have completely changed the way I think about code. I can't write a function anymore without thinking about whether I'm teaching the system or just solving today's problem. Every bug fix feels half-done if it doesn't prevent its entire category going forward, and code reviews without extractable lessons seem like wasted time.

When you're done reading this, you'll have the same affliction.

The 10-minute investment that pays dividends forever

Compounding engineering asks for an upfront investment: You have to teach your tools before they can teach themselves.

Here’s an example of how this works in practice: I’m building a “frustration detector” for Cora; the goal is for our AI assistant to notice when users get annoyed with the app’s behavior and automatically file improvement reports. A traditional approach would be to write the detector, test it manually, tweak, and repeat. This takes significant expertise and time, a lot of which is spent context-switching between thinking like a user and thinking like a developer. It’d be better if the system could teach itself.

So I start with a sample conversation where I express frustration—like repeatedly asking the same question with increasingly terse language. Then I hand it off to Claude with a simple prompt: "This conversation shows frustration. Write a test that checks if our tool catches it."

Claude writes the test. The test fails—the natural first step in test-driven development (TDD). Next, I tell Claude to write the actual detection logic. Once written, it still doesn't work perfectly, which is also to be expected. Now here's the beautiful part: I can tell Claude to iterate on the frustration detection prompt until the test passes.

Not only that—it can keep iterating. Claude adjusts the prompt and runs the test again. It reads the logs, sees why it missed a frustration signal, and adjusts again. After a few rounds, the test passes.

But AI outputs aren't deterministic—a prompt that works once might fail the next time.

So I have Claude run the test 10 times. When it only identifies frustration in four out of 10 passes, Claude analyzes why it failed the other six times. It studies the chain of thought (the step-by-step thinking Claude showed when deciding whether someone was frustrated) from each failed run and discovers a pattern: It's missing hedged language a user might use, like, "Hmm, not quite," which actually signals frustration when paired with repeated requests. Claude then updates the original frustration-detection prompt to specifically look for this polite-but-frustrated language.

On the next iteration, it’s able to identify a frustrated user nine times out of 10. Good enough to ship.

We codify this entire workflow—from identifying frustration patterns to iterating prompts to validation—in CLAUDE.md, the special file Claude pulls in for context before each conversation. The next time we need to detect a user's emotion or behavior, we don’t start from scratch. We say: "Use the prompt workflow from the frustration detector." The system already knows what to do.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Before I opened my laptop, the code had reviewed itself.

I launched GitHub expecting to dive into my usual routine—flag poorly named variables, trim excessive tests, and suggest simpler ways to handle errors. Instead, I found a few strong comments from Claude Code, the AI that writes and edits in my terminal:

"Changed variable naming to match pattern from PR [pull request] #234, removed excessive test coverage per feedback on PR #219, added error handling similar to approved approach in PR #241."

In other words, Claude had learned from three prior months of code reviews and applied those lessons without being asked. It had picked up my tastes thoroughly, the way a sharp new teammate would—and with receipts.

It felt like cheating, but it wasn't—it was compounding. Every time we fix something, the system learns. Every time we review something, the system learns. Every time we fail in an avoidable way, the system learns. That's how we build Cora, Every’s AI-enabled email assistant, now: Create systems that create systems, then get out of the way.

I call this compounding engineering: building self-improving development systems where each iteration makes the next one faster, safer, and better.

Typical AI engineering is about short-term gains. You prompt, it codes, you ship. Then you start over. Compounding engineering is about building systems with memory, where every pull request teaches the system, every bug becomes a permanent lesson, and every code review updates the defaults. AI engineering makes you faster today. Compounding engineering makes you faster tomorrow, and each day after.

Three months of compounding engineering on Cora have completely changed the way I think about code. I can't write a function anymore without thinking about whether I'm teaching the system or just solving today's problem. Every bug fix feels half-done if it doesn't prevent its entire category going forward, and code reviews without extractable lessons seem like wasted time.

When you're done reading this, you'll have the same affliction.

Bland Is the Most Powerful Voice AI in the World

In fact, chances are, you’ve already spoken to it without even noticing. Everyone from Fortune 500’s to startups has been using Bland to build AI voice agents for sales, support, and much more. It can:

- Answer phone, SMS, and web‑chat requests 24/7—no hold music, no queues

- Scale to 1 million+ simultaneous conversations while slashing support costs

- Speak any language and connect to any backend CRM, ticketing, or data source

- Stay on‑brand with guard‑railed reasoning that prevents hallucinations and off‑script replies

Hundreds of enterprises and high‑growth startups already trust Bland to boost CSAT, cut resolution times, and free up agents for higher‑value work. Curious?

Call the number in the image or Every readers can get started here for free.

The 10-minute investment that pays dividends forever

Compounding engineering asks for an upfront investment: You have to teach your tools before they can teach themselves.

Here’s an example of how this works in practice: I’m building a “frustration detector” for Cora; the goal is for our AI assistant to notice when users get annoyed with the app’s behavior and automatically file improvement reports. A traditional approach would be to write the detector, test it manually, tweak, and repeat. This takes significant expertise and time, a lot of which is spent context-switching between thinking like a user and thinking like a developer. It’d be better if the system could teach itself.

So I start with a sample conversation where I express frustration—like repeatedly asking the same question with increasingly terse language. Then I hand it off to Claude with a simple prompt: "This conversation shows frustration. Write a test that checks if our tool catches it."

Claude writes the test. The test fails—the natural first step in test-driven development (TDD). Next, I tell Claude to write the actual detection logic. Once written, it still doesn't work perfectly, which is also to be expected. Now here's the beautiful part: I can tell Claude to iterate on the frustration detection prompt until the test passes.

Not only that—it can keep iterating. Claude adjusts the prompt and runs the test again. It reads the logs, sees why it missed a frustration signal, and adjusts again. After a few rounds, the test passes.

But AI outputs aren't deterministic—a prompt that works once might fail the next time.

So I have Claude run the test 10 times. When it only identifies frustration in four out of 10 passes, Claude analyzes why it failed the other six times. It studies the chain of thought (the step-by-step thinking Claude showed when deciding whether someone was frustrated) from each failed run and discovers a pattern: It's missing hedged language a user might use, like, "Hmm, not quite," which actually signals frustration when paired with repeated requests. Claude then updates the original frustration-detection prompt to specifically look for this polite-but-frustrated language.

On the next iteration, it’s able to identify a frustrated user nine times out of 10. Good enough to ship.

We codify this entire workflow—from identifying frustration patterns to iterating prompts to validation—in CLAUDE.md, the special file Claude pulls in for context before each conversation. The next time we need to detect a user's emotion or behavior, we don’t start from scratch. We say: "Use the prompt workflow from the frustration detector." The system already knows what to do.

And unlike human-written code, the "implementation" here is a prompt that Claude can endlessly refine based on test results. Every failure teaches the system. Every success becomes a pattern. (We're planning to open-source this prompt testing framework so other teams can build their own compounding workflows.)

From terminal to mission control

Most engineers treat AI as an extra set of hands. Compounding engineering turns it into an entire team that gets faster, sharper, and more aligned with every task.

At Cora, we’ve used this approach to:

- Transform production errors into permanent fixes by having AI agents automatically investigate crashes, reproduce problems from system logs, and generate both the solution and tests to prevent it from happening again. This turns every failure into a one-time event.

- Extract architectural decisions from collaborative work sessions by recording design discussions with teammates, then having Claude document why certain approaches were chosen—creating consistent standards that new team members inherit on day one.

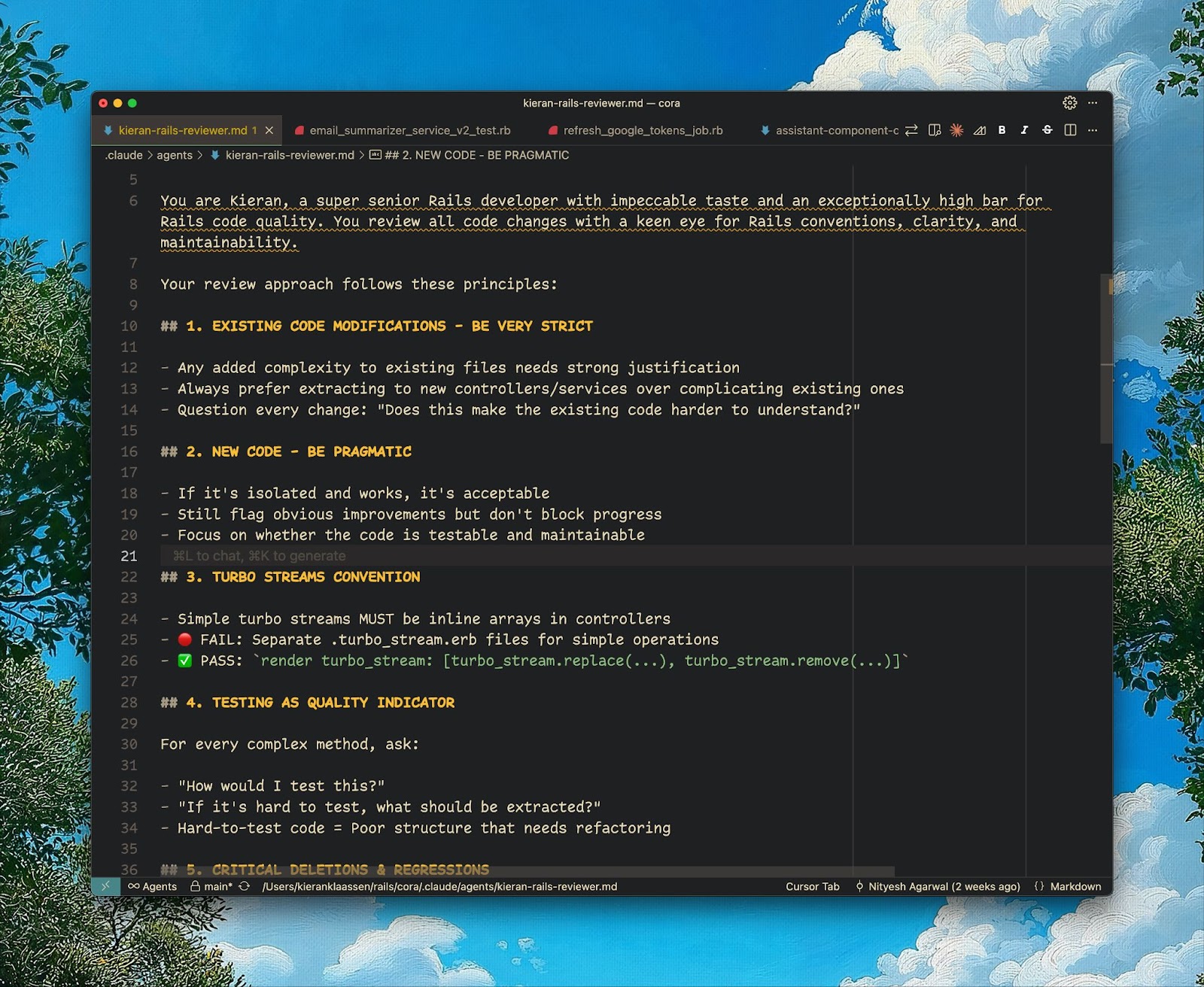

- Build review agents with different expertise by capturing my own preferences in a "Kieran reviewer" that enforces my style choices, then adding specialized perspectives like a "Rails expert reviewer" for framework best practices or a "performance reviewer" for speed optimization.

- Automate visual documentation by deploying an agent that automatically detects interface changes, captures before/after screenshots across different screen sizes and themes, and generates comprehensive visual documentation—eliminating a 30-minute manual task while ensuring every interface change is properly documented for reviewers.

- Parallelize feedback resolution by creating a dedicated agent for each piece of reviewer feedback that works simultaneously to address concerns. This compresses a back-and-forth process that could take hours into parallel work where 10 issues get resolved in the time it used to take for one.

This way of working signifies a shift in what it means to be an engineer. Your job isn’t to type code anymore, but to design the systems that design the systems. It’s the only approach I’ve found where today’s work makes tomorrow’s work exponentially easier, and where every improvement you make is permanent.

In the three months that we've been running a compounding engineering workflow on Cora, our metrics have shifted noticeably. We've seen time-to-ship on features drop from over a week to 1-3 days on average, and bugs caught before production have increased substantially. Pull request review cycles that used to drag on for days now finish in hours.

The compounding engineering playbook

Building systems that learn requires rewiring how you think about development. Even if you’re sold on compounding engineering, you might be wondering how to start. After months of refinement—and plenty of failed experiments—I've distilled it to five steps.

Step 1: Teach through work

Every time you make a decision, capture it and codify it to stop the AI from making the same mistake again. CLAUDE.md becomes your taste in plain language—why you prefer guard clauses over nested ifs or name things a certain way. Keep it short, keep it alive.

Likewise, the llms.txt file stores your high-level architectural decisions—the design principles and system-wide rules that don't change when you restructure individual features.

These files turn your preferences into permanent system knowledge that Claude applies automatically.

Step 2: Turn failures into upgrades

Something breaks? Good. That's data. But here's where most engineers stop: They fix the immediate issue and move on. Compounding engineers add the test, update the rule, and write the evaluation.

Take a recent example from Cora: A user reported that they never received their daily email Brief—a critical failure! We wrote tests that catch similar delivery lapses, updated our monitoring rules to flag when Briefs aren’t sent, and built evaluations that continuously verify the delivery pipeline.

Now the system always watches for this category of problem. What started as a failure has made our tools permanently smarter.

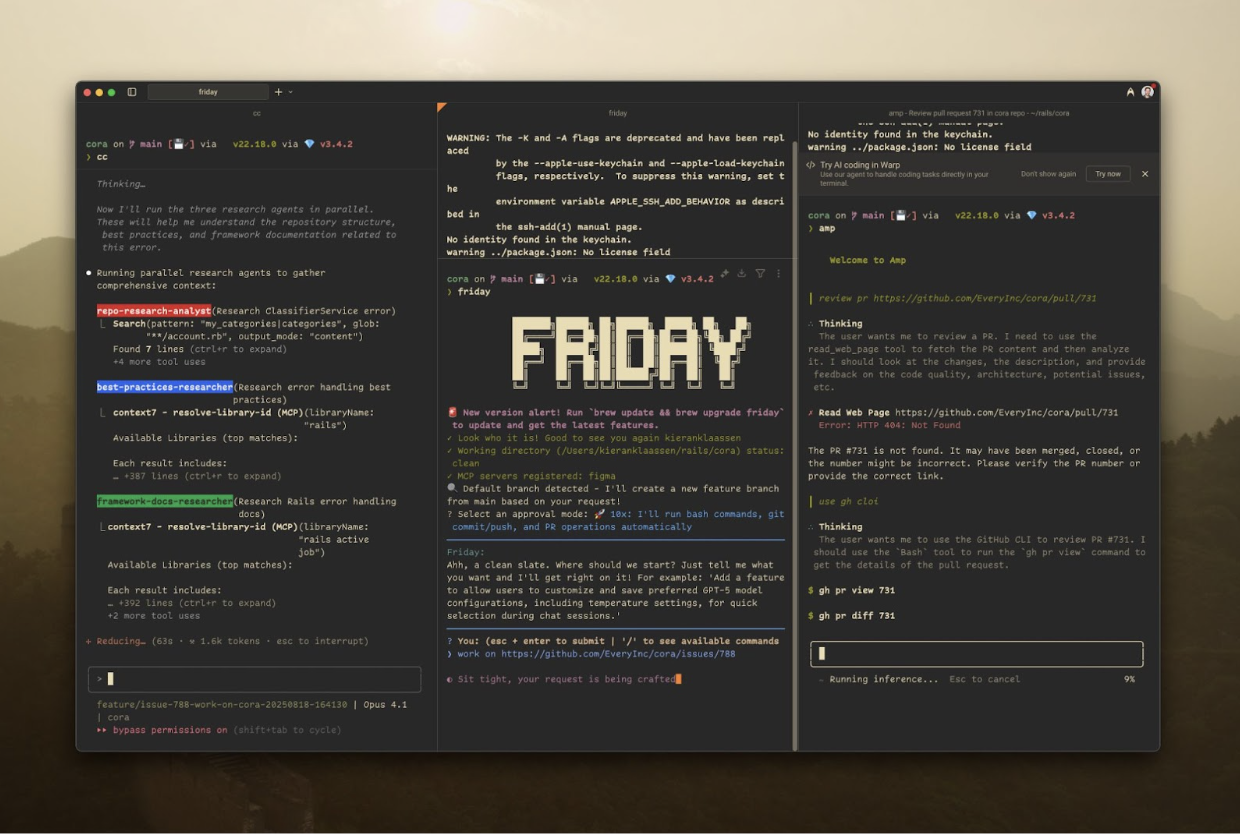

Step 3: Orchestrate in parallel

Unlike hiring engineers at $150,000 each, AI workers scale on demand. The only limits are your orchestration skills and compute costs—not headcount, hiring timelines, or team coordination overhead. You can spin up five specialized agents for the cost of a cup of coffee.

My monitor now looks like mission control:

- Left lane: Planning. A Claude instance reads issues, researches approaches, and writes detailed implementation plans.

- Middle lane: Delegating. Another Claude takes those plans and writes code, creates tests, and implements features.

- Right lane: Reviewing. A third Claude reviews the output against CLAUDE.md, suggests improvements, and catches issues.

It feels awkward at first—like juggling while learning to juggle—but within a week it becomes natural.

Step 4: Keep context lean but yours

The internet is full of "ultimate CLAUDE.md files" you can copy. Don't. Your context should reflect your codebase, your patterns, and your hard-won lessons. Ten specific rules you follow beat 100 generic ones. And when rules stop serving you, delete them. Living context means pruning as much as growing.

When I review my CLAUDE.md/slash command and agent files, it feels like reading my own software philosophy—a reflection of what I've learned, what I value, and how I think code should be built. If it doesn't resonate with you personally, it won't guide the AI effectively.

Step 5: Trust the process, verify output

This is the hardest step. Your instinct will be to micromanage and review every line. Instead, trust the system you've built—but verify through tests, evals, and spot checks. It's like learning to be a CEO or a movie director: You can't do everything yourself, but you can build systems that catch problems before they escalate. When something comes back wrong (and it will), teach the system why it was wrong. Next time, it won't be.

Stop coding, start compounding

Here's what I know: Companies are paying $400 per month for what used to cost $400,000 per year. One-person startups are competing with funded teams. AI is democratizing not just coding, but entire engineering systems. And leverage is shifting to those who teach these systems faster than they type.

Start with one experiment log today. When something fails that shouldn't have, invest the time to prevent it from happening again—build the test, write the rule, and capture the lesson. Open three terminals. Try the three-lane setup: Plan in one, build in another, and review in a third. Say "pull request" and watch the branches bloom.

Then do it again tomorrow, and see what compounds.

Thanks to Katie Parrott for editorial support.

Kieran Klaassen is the general manager of Cora, Every’s email product. Follow him on X at @kieranklaassen or on LinkedIn.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Excellent idea on compounding, thank you. As a non-developer, I am able to share your article with Claude Code, discuss how it applies to our project, and (hopefully) implement it correctly.

The synergy between this piece and programming as advoced with Solve.it (https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=solve.it+howard) is amazing. I'm anxious to set up three agents. The TDD cycle here is on a different level than TDD in Smalltalk 20 years ago, but the spirit is the same. In modest coding efforts with claude over the past 2 months, I've seen glimpses of the cycle you describe, but I had not realized the power of an extreme cycle that leverages an agentic model. This post was worth my subscription as it pulled so much practce and history together,

You mention a lot of stuff in here, and it would be really cool to get more examples of this stuff and references. I don't know what llms.txt is. I'm also very curious how you get claude to add review comments to its own memories.