Hello Every readers! This is part three of our ongoing series Rethinking Resilience with three-time founder and executive coach Jason Shen.

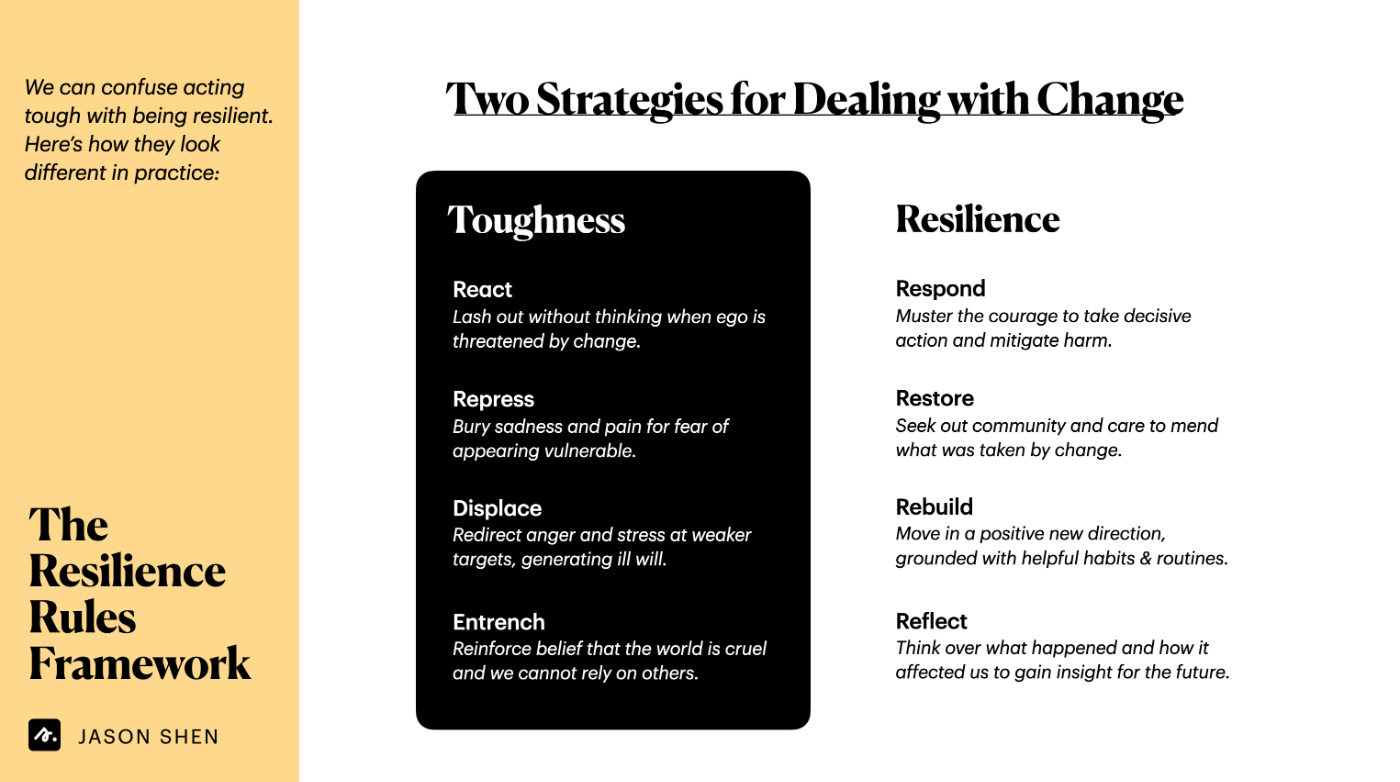

In this week's installment, Jason is examining one of the most persistent ideas when it comes to resilience: that the best way through any tough situation is to tough it out—to "man up" and fight your way through. We've all heard the saying: "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." But how effective is "toughness" as a resilience strategy, really?

If you missed parts one and two of Rethinking Resilience, you can find them here:

- How to Cultivate Resilience: A Four Part Framework

- Oh Shit, You're Going Through a Reorg

Here's Jason!

When I was eight years old, after years of scrimping and saving, my immigrant parents put a down payment on our first house. I started fourth grade at a new school and quickly learned that my new classmates seemed openly disrespectful to teachers and liked to mimic pro wrestling moves on each other (and anyone nearby). They seemed to hate me for the way I looked and the way I loved to read; I was called “chink” and “four eyes” and occasionally got jumped after school. This went on for years. At one point, my parents even considered pulling me out of public school.

But I stayed long enough for a couple of things to make a difference in how I was treated: I finally talked back to one of my bullies during recess and didn’t back down from the fight that ensued, and I hit puberty in 7th grade. My years of gymnastics training put some muscle on my body—and I got contacts.

When I was going through them, I mostly reasoned that my struggles in school were just part of the typical skinny nerd experience. But in my adulthood, I’ve realized that growing up as an Asian American male meant learning to overcompensate for a perceived lack of masculinity due to my ethnic background—speaking and acting more aggressively than I otherwise would like to, in order to project strength. In my early twenties I ran a blog called “The Art of Ass-Kicking” and made every effort to project a fearless, give-no-fucks attitude.

Now in my thirties, I’ve stepped back from that mentality and am settling into a more healthy relationship with my gender and how others perceive me. I’ve learned to see strength differently.

When we’re going through a period of adversity or change—be it disagreeable coworkers, a health challenge, or a period of unemployment—we’re often told to “toughen up.” In tech, we see it in the folks who seek to emulate Steve Jobs or Linus Torvald’s scathing criticism and harsh language in the name of “ruthless honesty.” We see it in the adoration of Elon Musk, who told his first wife he was an “alpha” and thus his needs would always supersede hers.

Hello Every readers! This is part three of our ongoing series Rethinking Resilience with three-time founder and executive coach Jason Shen.

In this week's installment, Jason is examining one of the most persistent ideas when it comes to resilience: that the best way through any tough situation is to tough it out—to "man up" and fight your way through. We've all heard the saying: "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." But how effective is "toughness" as a resilience strategy, really?

If you missed parts one and two of Rethinking Resilience, you can find them here:

Here's Jason!

When I was eight years old, after years of scrimping and saving, my immigrant parents put a down payment on our first house. I started fourth grade at a new school and quickly learned that my new classmates seemed openly disrespectful to teachers and liked to mimic pro wrestling moves on each other (and anyone nearby). They seemed to hate me for the way I looked and the way I loved to read; I was called “chink” and “four eyes” and occasionally got jumped after school. This went on for years. At one point, my parents even considered pulling me out of public school.

But I stayed long enough for a couple of things to make a difference in how I was treated: I finally talked back to one of my bullies during recess and didn’t back down from the fight that ensued, and I hit puberty in 7th grade. My years of gymnastics training put some muscle on my body—and I got contacts.

When I was going through them, I mostly reasoned that my struggles in school were just part of the typical skinny nerd experience. But in my adulthood, I’ve realized that growing up as an Asian American male meant learning to overcompensate for a perceived lack of masculinity due to my ethnic background—speaking and acting more aggressively than I otherwise would like to, in order to project strength. In my early twenties I ran a blog called “The Art of Ass-Kicking” and made every effort to project a fearless, give-no-fucks attitude.

Now in my thirties, I’ve stepped back from that mentality and am settling into a more healthy relationship with my gender and how others perceive me. I’ve learned to see strength differently.

When we’re going through a period of adversity or change—be it disagreeable coworkers, a health challenge, or a period of unemployment—we’re often told to “toughen up.” In tech, we see it in the folks who seek to emulate Steve Jobs or Linus Torvald’s scathing criticism and harsh language in the name of “ruthless honesty.” We see it in the adoration of Elon Musk, who told his first wife he was an “alpha” and thus his needs would always supersede hers.

Picture this:

- An overworked senior engineer tells a new grad “suck it up and don’t be a bitch” when they express concern about crushing deadlines

- A cutthroat, cover-your-ass workplace where execs yell at directors, who yell at managers, who yell at individual contributors, in vicious cascade of harassment and displacement of pain and feelings of powerlessness.

The philosophy of toughness tells us that the world is a cold, cruel place, so we too must be cold and cruel to survive in it. It demands that when you feel powerless or out of control, you must exercise power over others, and seek to control them.

Part of my goal with Rethinking Resilience is to debunk harmful myths that lead us away from living and working with purpose and hold us back from meaningful progress. And the idea that we should be able to just “tough it out” through any setback is one of the most pernicious and harmful myths of all.

Social scientists have reached consensus on how traditional ideas of “toughness”, which often get tangled up in gender norms, can harm more than they help. In late 2018, the American Psychological Association (APA) completed a decade-long project to issue guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men which focused on the specific challenges this population can face. They note the disproportionate rate of suspension and expulsion among male students, higher rates of suicide attempts resulting in fatality, substance abuse, incarceration, and early mortality as well as struggles with relationships, and decreased rates of seeking help for mental and physical health issues.

The guidelines laid out a framework for what many researchers have collectively termed “traditional masculinity”:

“Although there are differences in masculinity ideologies, there is a particular constellation of standards that have held sway over large segments of the population, including: anti-femininity, achievement, eschewal of the appearance of weakness, and adventure, risk, and violence.”

The more men adhered or agreed with these “standards” of masculinity, the more they engaged in unhealthy behaviors like heavy drinking and smoking, while ignoring things like preventative health care or seeking mental health resources.

These behaviors, as well as the standards they are coupled with, might appear to be what we think of as “tough”—working things out alone; not feeling (or at least not expressing) pain, uncertainty, or doubt; and dominating (perhaps “crushing”) any problem. “Tough times don’t last, tough people do.” Tackle the stress and hardship alone, without complaint, and bulldoze whoever you have to to achieve your goals.

All of us, regardless of gender identity, are bombarded with these kinds of messages, which perpetuate the idea that to be tough is to be strong. But when we act tough—when we focus on being dominant, being self-reliant, avoiding opportunities to be emotionally vulnerable and open by asking for help—we harm ourselves, and we become far less likely to help others [Note: In a survey of 10,000 American adults, researchers found that those who agreed with sexist beliefs including that men were biologically superior to women or that gender hierarchies ought to be maintained were “less likely to be worried about the coronavirus, less likely to engage in behaviors to protect themselves and others, less likely to support state and local government policies that aim to stem the spread of the disease, and finally, are more likely to get sick themselves”.].

[Note: In a survey of 10,000 American adults, researchers found that those who agreed with sexist beliefs including that men were biologically superior to women or that gender hierarchies ought to be maintained were “less likely to be worried about the coronavirus, less likely to engage in behaviors to protect themselves and others, less likely to support state and local government policies that aim to stem the spread of the disease, and finally, are more likely to get sick themselves”.].

Resistance and resilience can’t coexist. If toughness—defensive, closed-off, holding ground— is your only response to change, you lose the opportunity to learn. “Suck it up” isn’t a solution.

Returning to the earlier example of the stressed out senior engineer who snaps at the recent grad: this is a classic example of reacting in the moment and displacing aggression by blaming the new employee for being incompetent. Two actions that protect the ego in the moment and make the more tenured employee seem more intimidating, but do little to improve the situation for anyone.

Imagine if that senior engineer said, “To be honest, it’s been a hard couple of weeks for me too. Let’s gather some more data and present possible solutions to the eng manager.” These simple acts of resilience—restoring a sense of connection between the two team members through an admission of shared struggle and rebuilding with a constructive path forward—might actually lead to a more productive, and happier, engineering team!

Art Competition - Scotch and Bean #040From Captain America leading group therapy sessions in Avengers: Endgame to Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanianian decrying the toxicity of hustle culture and encouraging parental leave for fathers, I see encouraging signs across our society that we are slowly writing a new story for masculinity—one that downplays its more toxic elements, hopefully in order to make way for its strengths [Note: Psychologists Matt Englar-Carlson and Mark Kiselica developed a framework in 2010 for positive masculinity rooted in “strength, courage, bravery, valor, heroism, loyalty, and ‘generative fatherhood’” as a counterpoint to toxic masculinity.]. But the philosophy of toughness is a seductive one. It promises an emotional invincibility in the same way that a new credit card promises interest-free payments: you might feel pretty good for a while, but the bill always comes due.

[Note: Psychologists Matt Englar-Carlson and Mark Kiselica developed a framework in 2010 for positive masculinity rooted in “strength, courage, bravery, valor, heroism, loyalty, and ‘generative fatherhood’” as a counterpoint to toxic masculinity.]. But the philosophy of toughness is a seductive one. It promises an emotional invincibility in the same way that a new credit card promises interest-free payments: you might feel pretty good for a while, but the bill always comes due.

Living with resilience means accepting a more complicated view of the world, one without catchy slogans and risk-free guarantees. But when we choose to practice the skills of resilience, we are more likely to create good outcomes—for ourselves and others.

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Fantastic post, I've really been enjoying this series. Thank you, Jason!