Hello, Every readers! We're excited to introduce our new series, Rethinking Resilience.

The past few years have been challenging, to put it mildly. From supply chain problems to inflation, layoffs to a once-in-a-generation pandemic, we've all been navigating conditions that have left many of us feeling deflated and depleted. And that makes the idea of resilience more relevant than ever.

Over the next few weeks, three-time founder and executive coach Jason Shen is going to take us on a journey through the concept of resilience: where it comes from, how to develop it, and some of the misconceptions that might stand in the way of us cultivating a more resilient self. We hope this series equips you with the tools and the inspiration to take on the setbacks in your own life.

Stay tuned for future installments of Rethinking Resilience, coming to an inbox near you every Monday.

We'll let Jason take it from here!

Hi, I’m Jason. I’m a three-time startup founder and executive coach. My last company was acquired by Meta, where I currently lead product for Public Groups on Facebook. In my off-hours, I maintain a small coaching practice helping tech leaders to move through adversity and build things that matter.

In business, change represents both an opportunity and a threat. For the established players and incumbents, a change in consumer behavior, distribution platforms, and marketplace dynamics means their accumulated advantages are waning. For new entrants and innovators, change means an opening has emerged, where with nimbleness and agility they can find a foothold and grow.

In the last two years, I’ve developed a framework for cultivating resilience. From serial entrepreneurship and product management, to my years as an NCAA athlete and growing up a first-generation immigrant, I've endured a ton of change in many domains of my life. I've got stories to share, from fighting a baseless copyright infringement case to seeing my startup’s bank account drop below zero during a fundraising period. Layoffs, reorgs, hypergrowth, burnout, financial stress, illness, pandemics, supply chain upheaval and more—life comes at us fast and we can’t always see change coming. But we can build our capacity to handle change and uncertainty.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll tell stories, answer questions, and share practical strategies to help you overcome the hurdles in your life, and help others too. Because while we can’t always stop the downpour, we should be ready to lead our people—and deliver ourselves—to higher ground.

Here’s how.

Defining Resilience

Let’s start with some definitions. “Resilience” was first used in the physical sciences to describe a material's ability to absorb energy and return to its original shape after being deformed. In this definition, rubber has a really high degree of resilience. You can pull and bend and compress rubber, and it will generally return back to its original form. It springs back.

But even rubber isn't infinitely resilient. If you stretch rubber enough or apply enough pressure, it will tear and not return to its original form. Having a high degree of resilience does not make you invulnerable, it makes you less likely to tear.

For living beings like you and me, consider the windsurfer. To be successful as a windsurfer you have to be able to adapt. When the water current shifts or the winds change, the surfer has to adjust their body’s posture and how they’re holding the sail in order to navigate through. When our lives hit some turbulence, we have to be able to ride the bumpy parts.

The definition I use for resilience is the ability to adapt effectively in the face of adversity and change. Most of us can adapt at least a little to a small amount of change. But the bigger the change or challenge, the harder it is to adapt. Cultivating resilience means building the tools and habits of mind to scale your ability to adapt.

The Three Myths of Resilience

Before we get into how we can cultivate resilience, I do want to spend some time on what I consider some of the myths or false beliefs about resilience. These are things that we have to unlearn if we are going to be successful in adapting to change.

Resilience is not a trait or a resource—it’s a skill.

Many people make the mistake of seeing resilience as a kind of inborn trait. One that you inherit, like eye color or freckles or height. While there may be some aspects of resilience that are inherited(inherent optimism, overall energy levels), your intentional mindset and proactive behavior towards change matters more.

It’s also not a resource like savings in your bank account, where you can just save up resilience credits and then spend it when you need it. Instead, think of resilience as a skill. More specifically, a set of skills that you can learn, practice, and improve. I will never be as good at shooting three-pointers as Steph Curry, but with training, I sure as hell can get a lot better than I am now. So it is with resilience.

Resilience does not mean being self-reliant—it means relying on and being reliable to others.

The second myth that I want to debunk is this idea of self-reliance. That resilient people do it all themselves. They’re independent, they don't need anybody else. That could not be further from the truth. Any organization, any person, any community that is resilient is one where people are coming together, where there is outside support, where there is shared contribution toward a shared future.

We have to let go of this idea that if someone was really tough, they could do it on their own—it’s just not true, and never has been. Don't do it alone. Don't try to be a tough guy.

Resilience isn’t just about sucking it up and powering through. It requires building relationships, give and take, contributing to the greater good, and asking for help. The dream of living off the land, alone from everyone else is an idealized myth that’s rooted in the rapacious expansion of this nation (a topic I’ll explore in my next piece). It’s not an easy thing to let go of, but it needs to be dismantled for a mindset that values mutual aid and collaboration.

Resilience is not just thinking and planning ahead of time—it requires flexibility and feelings of uncertainty.

Finally, being resilient doesn’t mean purely planning and anticipating every problem before it happens. Some people try to control every variable to prevent bad things from happening. Account for every risk. Bring extra supplies and leave buffer time on the schedule. Create financial forecasts. Have safety protocols.

Of course these efforts can reduce the headache from known problems. But our world is too complex to account for every contingency. A policy change from a big tech company throws an entire industry off balance, resulting in layoffs, market fluctuations, and new opportunities to emerge. An investigative news story leads to the resignation of a senior leader, creating a power vacuum that veterans and emerging players jockey to fill. The more everyone tries to plan everything, the more unexpected results trigger a shift in outcomes.

Resilience is a process. In software, we now focus more on continuous deployment and monitoring rather than super comprehensive test suites and Q&A. It’s not that those latter things aren’t important, but it’s even more effective—and possible—to ship new code and be able to roll back quickly if needed, rather than anticipate every potential problem.

This mentality of overplanning and overanalyzing is also flawed because it treats everything like a mental puzzle to be solved. There’s a lot about resilience that’s emotional in nature. Being able to parse through your feelings, expressing those feelings (especially the uncomfortable ones) to people around you, asking for help, developing compassion for your mistakes and forgiving others: these require a different kind of effort. For many people, emotional awareness and vulnerability may be foreign and scary, but they are essential to resilience.

The Four Skills of Resilience

This framework is designed to help anyone experiencing uncertainty, adversity, and change. It’s drawn from my own experiences as a serial entrepreneur, a product leader, and an executive coach working with innovative leaders in turbulent times.

So while this framework applies in any system or context, it was designed for those seeking to navigate disruptive change in order to bring new products, stories, and ideas into the world. The goal is to help you move forward with greater clarity and stronger wellbeing. In a future post, I’ll show you how to apply each of these skills in the specific context of a reorg—something you’re likely to experience in the years ahead, if you haven’t already...

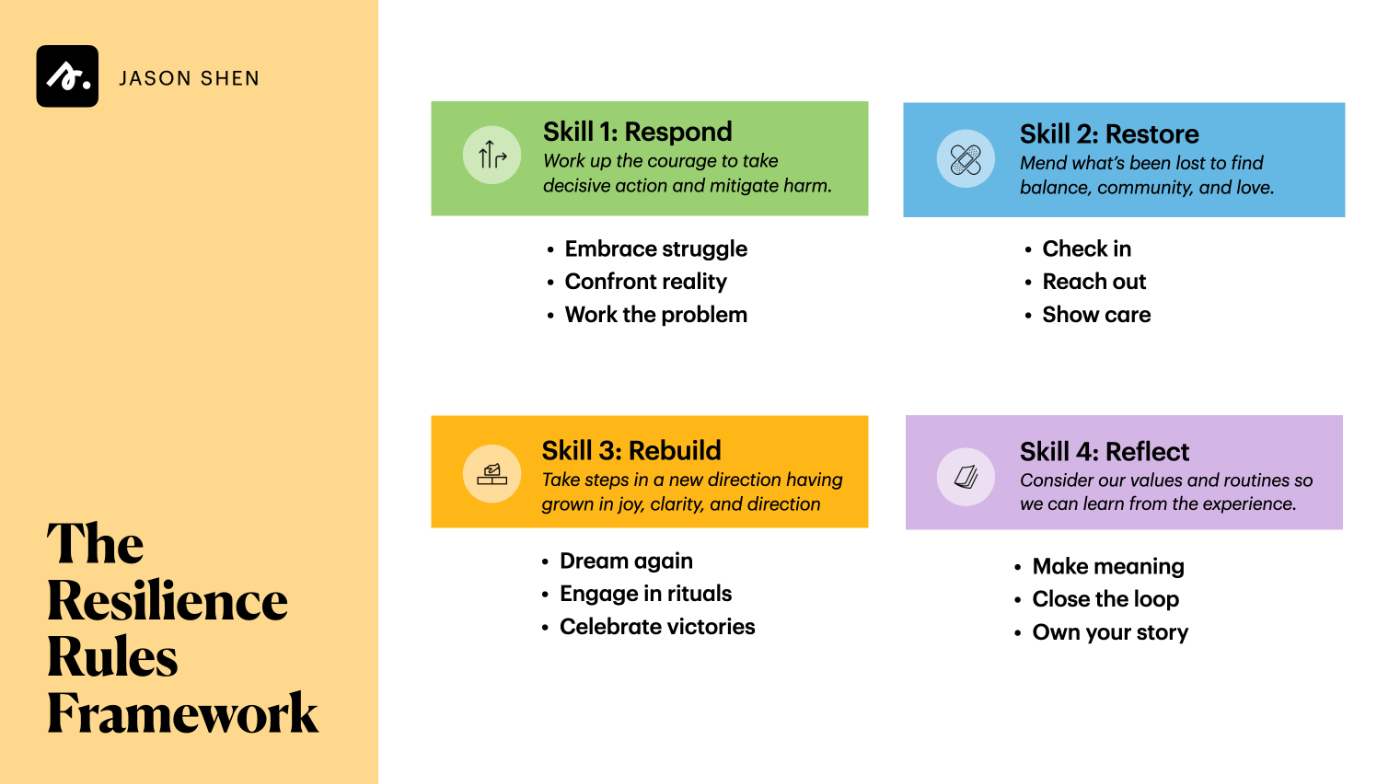

Resilience is a set of four primary skills: respond, restore, reflect, rebuild. As you may have noticed, resilience and each of its four skills start with the prefix “re,” which has its roots in the Latin for “back,” “again,” “against,” and “anew,” and can be traced to the Proto-European “wret,” meaning “to turn.” Because the heart of resilience is confronting setbacks, obstacles, and changes that push you off your path, forcing you to begin again.

While I’ve labeled them as a sequence from 1 through 4, they are not strictly speaking a step-by-step process. Depending on what kind of change you’re experiencing and where you find yourself, you may find more value starting at Reflect before going to Respond, or something else. But if you’re wondering how to begin, you can go ahead and follow this order until you’re able to adapt these skills to your specific circumstance and needs.

Skill 1: Respond

In early 2020, my startup Midgame was poised to present an exciting vision of our voice-enabled gaming assistant to the world at a Betaworks-sponsored Demo Day when COVID lockdowns began. The fundraising landscape changed instantly and we realized our vision was not going to be fundable. Within a week, we had responded to this massive external shift and started working on new concepts geared towards a quarantined world. Those ideas didn’t pan out but it led to our eventual acquisition.

The first skill is to respond to the new circumstances of change. It makes some sense, right? Responding is when you’re first encountering the fact that your world is not the same as it was, and that things are different in little and big ways.

There are three rules for responding to change:

Embrace the struggle. The first powerful step is accepting the reality of change—we're always going to be living with it, through it, and in it. When we accept change, we ready ourselves for its arrival; when we deny the inevitability of change, we leave ourselves flat footed.

Change can cause stress and discomfort even if we know it’s coming. But embracing this can help us see the possibility of our own growth. If you think back to your own moments of personal growth, they probably came during or after periods of intense stress and struggle. This isn’t to say all hardship leads to gain, but desiring to never experience stress is both unrealistic and unwise. It can keep us from seeing the many good things that can come with change.

Confront reality. This next rule is about seeing clearly. This requires collecting accurate and relevant data about your situation, observing things closely, and getting a fresh perspective on your problems. We are easily blinded by delusions and avoidance of the real issues, and in order to respond to change, we have to truly understand and make sense of what we are dealing with.

In the face of a rapidly declining memory chip business, Intel cofounders Gordon Moore and Andy Grove faced the very real prospect of being fired and replaced by the board. They asked themselves "Why can't we just do what the new CEO would do?" They laid off a third of their workforce (7,000 employees) and chose to double down on the nascent CPU business. Their decision to confront reality enabled Intel to survive when its competitors did not and lead the world in microprocessor manufacturing even to this day.

Work the problem. Take decisive action to prevent further harm. A ship captain knows there are things you can control—like how we hoist our sails and where we direct the rudder—and things we can’t—like the weather or the water conditions. An executive works the problem by focusing on the levers in their control, like their strategy and how well they execute, while letting go of the rest, like their short-term press coverage and stock price. During the ill-fated Apollo 13 crisis, NASA flight commander Gene Kranz used the mantra “work the problem” to focus mission control teams on solving the most urgent issues methodically in order to save the crew.

Skill 2: Restore

In my third year of collegiate gymnastics, I dislocated my knee in a double-twisting vault landing gone horribly wrong. I had to undergo multiple reconstructive surgeries, spent months in crutches and over a year in physical therapy. But eventually I returned to competition and we ultimately won an NCAA championship in my final season. Everyone understands that physical setbacks require time and support to heal, but we often don’t give ourselves that same grace when it comes to professional, social, or emotional challenges.

The second skill of resilience is to restore what change has altered. To mend what’s been lost through community and care.

Check in. This strategy is all about getting in touch with your emotions and internal experiences, and, if you’re a leader, with the experiences of the people you lead. How are you really doing? What has change thrown out of balance? What needs are no longer being met?

In all of my startups, I would regularly have “heart-to-heart” conversations with my cofounders about how we were feeling, outside of the day to day commitments of the business. This allowed us to support each other and avoid excessive founder conflict that business professor Noam Wasserman claims to tank 65% of high potential startups.

Scotch & Bean #038 - Finding Peace (by Jason Shen)

Reach out. This is about connecting with your larger community for dialogue and support. It could be to commiserate, ask for help, or share feedback on something that’s bothering you. It means admitting you need others and refusing the false call of “total independence.”

For many high achievers, asking for help might feel like admitting failure. But when you look past the headlines and fawning profile pieces, every successful person has benefited from an entire community of collaborators, benefactors, and friends. Social psychologist Heidi Grant writes in Harvard Business Review that “your performance, development, and career progression depend more than ever on your seeking out the advice, referrals, and resources you need,”, noting that more than ¾’s of the help co-workers give each other come from direct requests.

Show care. The third rule of restoring is offering kindness and compassion to yourself and the people around you. Showing care can mean really listening when someone comes to you with a problem. It means trying to see things from someone else’s perspective when you disagree. And it means forgiving yourself for mistakes and failures (an act that has been shown to reduce cortisol levels and increase life satisfaction).

It’s important to appreciate giving to others not just in a reciprocity kind of way—helping only because they helped you. It’s often the other way around. Even when you feel like you yourself have very little, helping others lets you know you have value and worth to share. It takes your mind off your own problems and can be a great form of relief and rejuvenation.

Skill 3: Rebuild

As I’ll share later on in this newsletter, I was once sued by a notorious copyright troll and forced to pay out a spurious five-figure settlement. I had to ask for a personal loan from several close friends to even make the payment. But once I put the matter behind me, I had the headspace to explore new ideas, like launching a paid cohort-based program with a designer who would later become my wife.

In the third skill of resilience, we begin again with a new understanding of ourselves and our aspirations. We start moving forward with joy and purpose, appreciating every step along the way.

Dream again. Change often takes away not just something from our present, but from our future. When your team gets reorganized or your project gets canceled, your hopes for the future are dashed and you have to find a new source of hope. In recovering from my gymnastics knee injury, I had to accept that I could not perform at the level I once could, and gave up my dream of representing the US in international competition.

This strategy asks us to mourn and let go of those old dreams, and find new areas of passion and excitement to carry us into the future. We have to develop a vision for something new. This might not happen overnight, but it is crucial to moving past the change.

Engage in ritual. This strategy is really about activating the power of behavior to shape our identity. Kursat Ozenc, a lecturer at Stanford University on organization and culture, writes that rituals can be a powerful strategy in facilitating change because they produce "intangible benefits of shared purpose, a sense of meaning, and community bonds.”

After a difficult situation, people and teams often seek to move through a meaningful set of actions to find closure and move forward: a funeral, an all-hands, a team dinner. And outside of those big one-off moments, daily rituals and practices can help us feel more grounded, prepared, and intentional about our life.

Celebrate victories. Sometimes when we have a big setback, we can feel like we're just behind where we used to be, and it can be hard to find the joy in that. Early on, progress towards our new dream can feel so small, like starting a fire, we have to nurture that flame. Research by Teresa Amabile has found that a sense of consistent progress is one of the important ways to nurture the inner work lives of creative professionals.

“The more positive a person’s mood on a given day, the more creative thinking he did the next day—and, to some extent, the day after that—even taking into account his moods on those later days,” writes Dr. Amabile in her book The Progress Principle. By seeking out and securing small wins, we can coax that kindling dream into a roaring bonfire. And by finding ways to bring joy, gratitude, and celebrations into our lives, we can keep that momentum going.

Skill 4: Reflect

For over a decade, I have taken time to reflect on and publish lessons that I learned about myself, my work, and the world. This has become a ritual (see above) that lets me mark another passing year while enabling me to be more skillful on what I do. This past year I shared 12 ideas, including “being successful does not necessarily feel good.” and “well-told stories are unreasonably persuasive”.

When our world changes, we must change with it. This means taking the time to consider and update even our most important values, beliefs, and systems so that we can learn from this experience.

Make meaning. One of the gifts of change is that it shows us what really matters in our lives. To experience stress is to feel discomfort when something you care about is at stake. We can decide that maybe this thing—getting a promotion at work, or being proven right about something—isn’t that important after all, and that can help us let go of some stress. Or we can decide that this thing really does matter to us, and in fact we should be putting even more effort and focus into this important matter so we can keep moving it forward.

Students who choose “bigger than self” goals are more curious, hopeful, caring, grateful, and excited compared to those who choose self-focused goals. When psychologists ask people to describe and share stories about how they lived up to their deepest values, they’re able to endure stress and hardship better.

Close the loop. Our bodies maintain a complex set of systems—oxygen, blood sugar, thermoregulation—all operated through a series of feedback loops that keep things in balance. Air Force strategist John Boyd taught pilots to use the OODA loop to combat a threat: observe, orient, decide, act. The idea was to take rapid action and study how your action changed the situation so that you could gain an advantage. Closing the loop means absorbing that new information, those lessons, and incorporating them back into your work. Often, change reveals a weakness in your system: a tightness in your left knee, an overexposure of a stock portfolio in a single industry, a single point of failure in a technical platform. Developing fail-safes and backup mechanisms ensure that these valuable lessons are not lost.

Own your story. We will inevitably be asked about our journey, our struggles, our past failures or errors. And so learning to tell that story to ourselves, our peers, strangers, and outside observers is the final strategy for resilience. Stories that ring true and reflect what matters to us can help us feel more empowered, build trust among those who are getting to know us, and position us to take on our new dream with confidence and purpose.

The Tradeoffs to Resilience

We’ve covered the key benefits of cultivating resilience, but it’s not a panacea. Just like any quality—speed, power, reliability, accuracy—investing effort in improving it means spending less elsewhere. There can be real downsides to making yourself, your team, and your organization more resilient to consider.

- Fewer massive upsides: Resilience requires, in part, spreading yourself out. Resilience means creating contingency options, setting aside additional resources in reserve, and not putting all your eggs in one basket. A balanced stock portfolio is less likely to lose money than throwing your cash in a meme stock, but it’s also less likely to go to the moon and bring you massive gains overnight. Resilience prioritizes downside protection over upside maximization.

- Reduced speed: To act with resilience can mean to take a bit longer to evaluate a situation and prepare ahead of taking action. Resilient entities rarely are the first-movers. A team focused on resilience may operate at a slower pace and miss out on some opportunities compared to those who prioritize “moving fast” or going “all in.”

- Release of control: A resilient mindset is one that understands not everything can be controlled and that calculated risks can go wrong. To operate with resilience is to be okay with failing or ending up in an unexpected or unplanned outcome. This lack of control and feeling of uncertainty can be uncomfortable for some who would rather have a tighter grip on the situation.

These drawbacks are real. But in a world characterized by increasing change and volatility, I have no doubt that building resilience would bring significant benefits for nearly everyone.

The past few years have felt like an avalanche of unrelenting change. The pandemic, the wildfires, the national reckoning on race, continued gun violence, increased polarization. There is no going back to the way things were before. Time only moves in one direction

But even as we mourn the world we’ve lost, we can use the skills of resilience to write our comeback story. Never forget that our species is endlessly adaptive. We’ve learned to live in nearly any climate and geography on Earth, feed off a diverse array of flora and fauna, cohabitate in a variety of lifestyles and cultures, and have scaled societies through devices and services that would appear as complete magic for those living just a few generations before us.

Resilience runs in our veins, and together we can cultivate that power to face whatever comes next. Over the next few weeks, I’ll share strategies, stories, and research that shows how to do just that.

Jason

PS - Let’s start a conversation. Reply to this email with one resilience-related question or challenge you’d love to get my thoughts on. And if you’re part of the Every Discord, you can DM directly!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This is really clear, thoughtful, interesting and helpful. Thanks for the great post!

Hi Jason, thank you for the detailed post. I’d like to hear your opinion on “owning your stories”. How do you ensure that the story you tell yourself is objective, by that I mean you take account for what gone wrong but not leave the burden entirely on yourself?