The moment that kicked off one of the most stressful 48 hours of my life began with a simple question over the phone.

“This is the Financial Crimes Division of the FBI. Are you aware you owe back taxes?”

It was March of 2017. I was working at Etsy, and the company had flown me and a coworker to California for a workshop hosted by Dan Ariely, a psychology professor at Duke. It was one of those early flights where you get off the plane and it’s still mid-day. The sun was shining and it felt a little surreal, like, “Why is it still so bright out?” I was tired, time-warped, 3,000 miles from where I’d been that morning in San Francisco, and waiting for a train when I got this strange call.

The Financial Crimes Division? I told myself this had to be fake. I’m just a regular guy! The caller seemed to anticipate my skepticism and instructed me to Google the number he was calling from. Sure enough, the search result for the number said “FBI.”

My heart dropped. I still held the lease to the address they mentioned, so maybe something had been sent there from the government that I’d missed. It felt totally plausible.

The voice on the phone said they had the ability to reach local law enforcement to arrest me if I didn’t cooperate, and even pulled the Caller ID trick on me a second time with the SFPD’s number to “prove it.” They said I needed to pay off my back taxes immediately. After the flight and in my dazed state, the last thing I wanted was for the police to show up at this workshop and arrest me. I was alone, I was scared, and I panicked. My brain shut down and I went into solution mode—just do as they say and this will all be over. That’s exactly what they told me.

For the next two days they continued to call me, a couple of guys from the same number. I could hear background noise on the calls; one speaker sounded East Asian, the other South Asian. They would vacillate between encouragement and threat. “You’re doing great, just keep doing what we say and you’ll be fine, this will be over soon.” Then they’d turn aggressive: “Do you want to be arrested? Is that what you want?”

Some photos from the workshop that I can barely remember

I was supposed to be learning how to apply behavioral psychology principles to product management alongside other product managers and startup founders, but I could barely pay attention. The man on the phone kept telling me not to tell anyone what was going on. Over and over they’d say, “Don’t tell or it’ll get worse.” It scared me even more—were things so bad that I could implicate someone else in my apparent financial crimes? They got me to buy Apple gift cards and give them the numbers, to reveal my credit card information and up my limits. They would threaten me, then extract information from me so that they gained real leverage. They raised the amounts they wanted, and I kept giving. It’ll all be over soon, they said, and said, and said.

After a couple of days of ducking out of the workshop to take their calls, I was in a car crossing the Golden Gate headed to a regional FBI office where someone could officially absolve me of my alleged sins, still on the phone. When it became clear that the traffic would cause me to miss the appointment, they told me the office would call me back to reschedule but that I was good.

At first, I felt relief—I’d done it! I’d made the scary FBI calls go away, even if it cost me a small fortune. But when the rescheduling call never came, that relief turned to dread. A sinking feeling came over me.

Oh my God, this was all fake, wasn’t it?

Those noises in the background of the calls? This was just a call center. The FBI threatening me and telling me to stay silent? This wasn’t a gangster movie! Suddenly everything became clear—how they manipulated me, played on my deepest fears and desires. I went into damage control, canceling cards, begging the customer service teams of my credit cards to forgive some of the payment, and trying to get in touch with the companies I’d bought gift cards from to recover any funds I could. I filed police reports with the city of San Francisco, whose police department told me I needed to file with the NYPD ostensibly because that’s where I now lived. My local police precinct in turn told me they couldn’t do anything because I was in San Francisco when it happened. I brought the total damage from $18,000 down to $12,000—nearly two months of my take-home pay.

I eventually confided in my girlfriend, now my wife. I was afraid she would shame or blame me for making such a stupid mistake. To my everlasting gratitude, she didn’t. Her biggest question was, “Why didn’t you call me when it was happening?”

The answer, of course, was that I was horribly embarrassed. While it was happening I just wanted to fix it, and afterwards I wanted to fix what I thought was my fixing it. What I realize now is how tactical all that was, the way the scammers switched from kind to cruel, pure manipulation. It was incredible to think that the workshop I was at with Professor Ariely was about how to help people make good decisions using positive psychology.

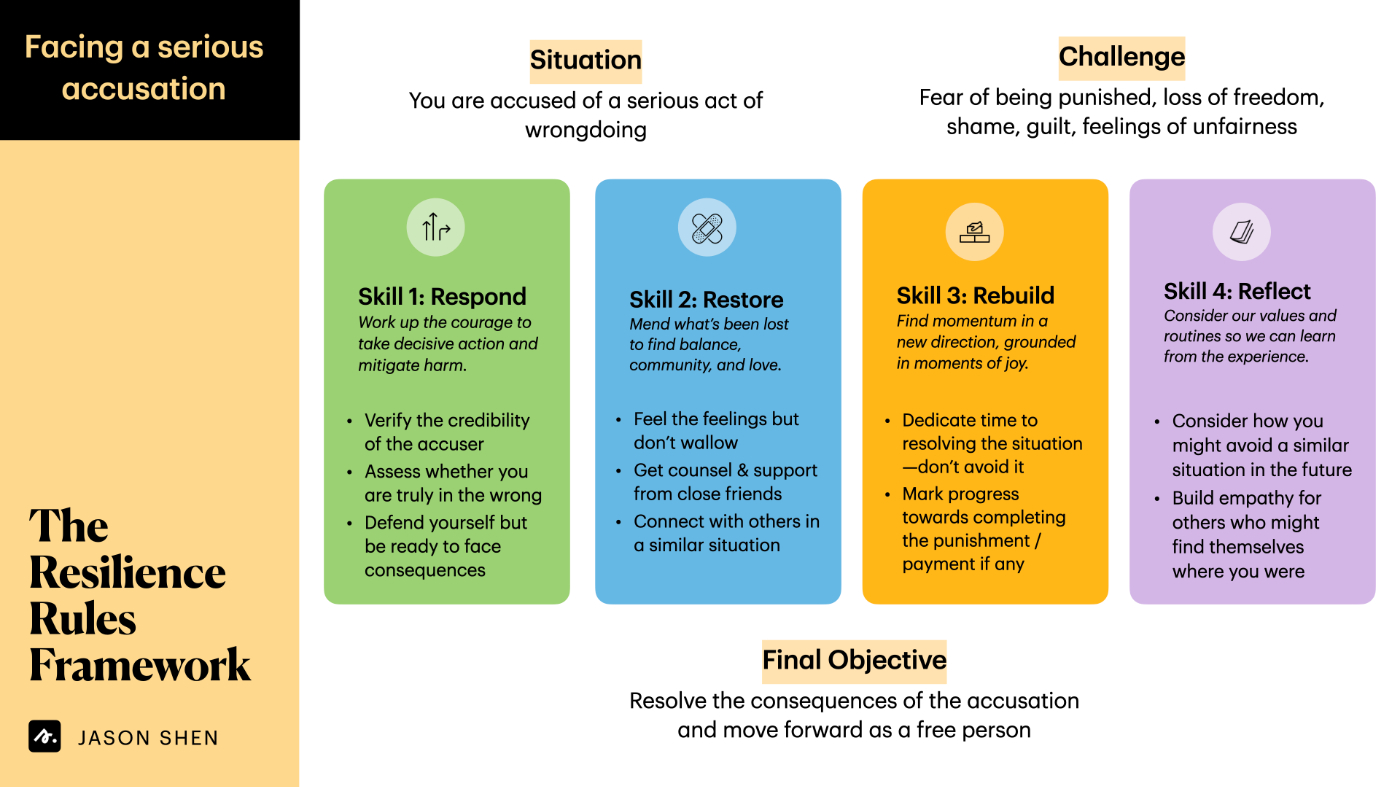

It took me much longer to understand why I was so powerfully manipulated by these obvious fraudsters. As a resilience coach, one of the most important things I can offer my clients is the space to unpack their shame and fear in a safe place. It’s through those countless sessions that I developed the resilience framework that I shared at the start of this mini-series.

While I think I moved through the first three skills—responding in the moment of the crisis, restoring my financial assets after losing the money, and rebuilding my confidence and mentality to unknown callers—I’m only now completing the final step of reflecting on the experience.

In order to write this piece, I had to re-examine two other traumatic events that happened earlier in my life. And in doing so I finally understood how I became so susceptible to this credit card scam.

. . .

When I was in college, I was arrested for driving a golf cart after I’d been drinking. I was on crutches at the time, going five miles an hour on an empty road on campus headed back to my dorm. I was charged with a DUI. I was sentenced to six weekends of “hard labor” in lieu of jail time, my license was suspended, I had to go to a rehabilitation class for alcoholics, and I was put on probation at my new job working for Stanford’s student newspaper. The degree I was supposed to receive several weeks from now would be withheld for a quarter. I’m not trying to shirk responsibility—I did get behind a wheel after too many drinks—but it felt like the punishment didn’t fit the crime.

I share this story not because I feel resentful, but to explain how this formative experience showed me what it felt like to be powerless. I remember thinking, “I’ve tried so hard to be a good person, so why am I being treated like a lawless criminal?”

I would have happily walked home if I didn’t have mobility issues, but in the end I chose to take a risk, one that could have hurt others. There’s a reason why drunk driving laws exist: 32% of fatal crashes at night involve intoxicated drivers. Yes, I wasn’t swerving, no one got hurt—but in terms of the law, this one was clear-cut. Still, I didn’t think I deserved such heavy punishment. To have to confess to my father. To have to face my peers and colleagues with this mark on my life, to have this on my record as a misdemeanor. It didn’t feel fair. I felt alone. I felt violated. I felt helpless. Once you’re caught up in the justice system, there is very little you can do. There is no escape button. And there might be no recourse at all.

Then there was the lawsuit.

A few years later, my ego a bit tender but my sense of the world still fundamentally positive, I started writing online. A piece I’d put on my blog got picked up by Hacker News and went viral—a first for me. The piece centered on an inspirational quote by a swim coach that I had come across years ago as an NCAA athlete, about how success required unusual effort.

I shared the 32-word quote with attribution to the author and explained what its message meant to me. I would go on to have several other popular blog posts and decided to organize a collection of my essays and sell them as a Kindle ebook on Amazon. I decided to title my book the same as the one written by the swim coach. Titles aren’t copyrightable, which is why there are dozens of songs on Spotify called “Secrets.”

I figured I wouldn’t be confusing anyone—his book was old, paperback only, and written for swimmers—while mine was newly published, digital only, and written for people in tech. Plus I had a different subtitle. It never occurred to me that my use of the title and the quotation would be anything other than homage, or inspiration—a jumping-off point, not something I was passing off as my own. In my view, I had done nothing wrong.

The author disagreed. A year later I received a cease-and-desist letter indicating I owed him royalties for reprinting his work and needed to pay him $1 for every view the article had received online—a sum that would come to more than $35,000.

I ignored it—wouldn’t you? This had to be spam, or a joke, or otherwise something I could and should disregard. There are a lot of crazy people out there in the world. It was 32 words from a book that appeared out of print on Amazon.

Ignoring the letter did not work. Some months later, I was served with papers in front of all my colleagues while at work. The author was officially suing me in the State of Texas.

I sought counsel from several lawyers, eventually hiring someone who had previously represented Microsoft in intellectual property cases. We tried to make the case that my book was covered under “fair use,” but the Texas judge assigned to our case wasn’t willing to toss the case without a trial: we would have to resolve the matter in court or settle.

A trial could take years and rack up legal fees of $100,000 or more, fees that might not be reimbursed even in the case of a win. Every day this case dragged on, I was shelling more money out of my meager savings as a recent grad to fight a case that in the best scenario would result in my not owing him any fines. My lawyer told me to settle. Eventually I did, taking down the blog post and withdrawing the book, promising to not disparage him (which is why I have to be so vague in this piece), and paying him $40,000 on top of the $10,000 I had paid my lawyer.

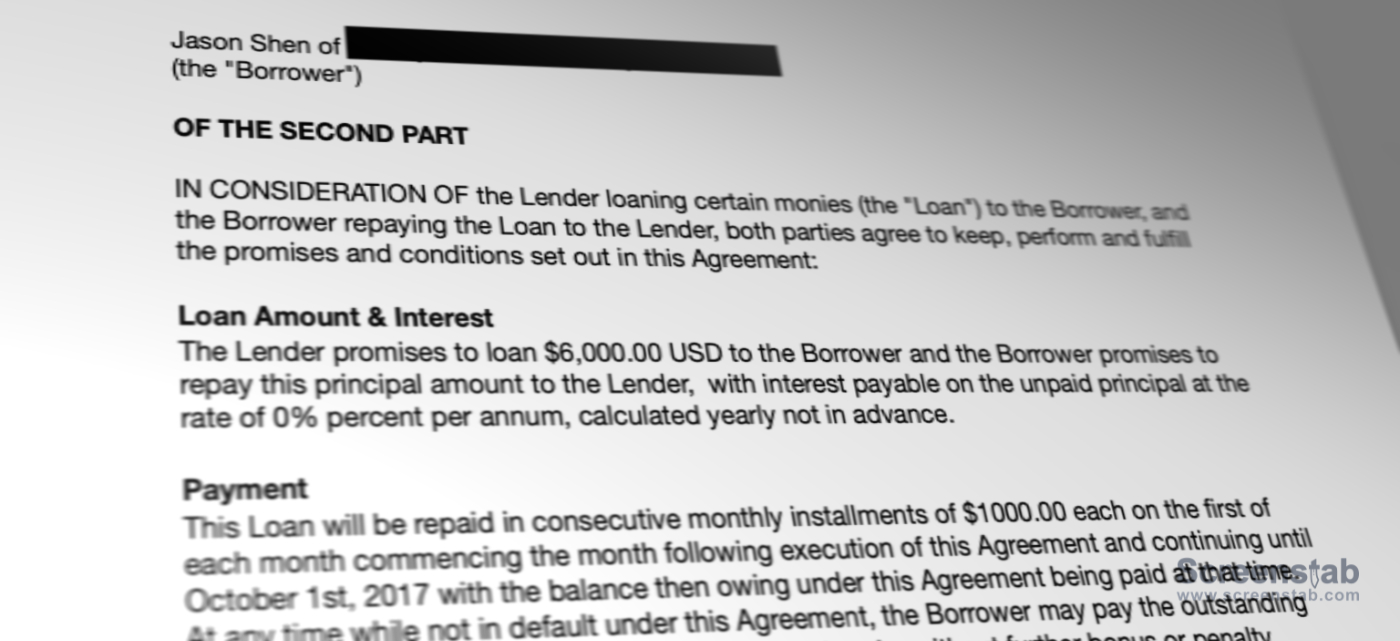

I was lucky not to have student loans thanks to an athletic scholarship and a lifetime of scrimping and saving by my immigrant parents. But I definitely didn’t have 50 grand lying around, either. I ended up working out a payment plan as part of the settlement and asking four close friends to lend me thousands of dollars each.

The personal loan agreements I drew up with several friends

To my horror, the man then sued dozens of others who had “stolen” his quote for motivational posters: gym teachers, ice skating instructors, a school district had to pay this man thousands to settle. I already felt shame for being, in my own eyes, too afraid to keep fighting. Now my settlement was being weaponized to bully and extract payment from others.

The process I went through was drawn out, painful, and impossible to understand. It wasn’t satisfying for me to call him an “evil guy,” but no amount of reasoning could help me understand why he had pursued me so doggedly. It appeared to be as simple as greed, injured pride, and the desire for revenge over someone who he felt had hurt him. There was nowhere for me to run. I had neglected to take the threat seriously, and months later, I was stuck in a process I could not reverse. I paid and tried to move on, my sense of safety in this world violated.

. . .

So I had once been accused of breaking the law, and it was real, and I learned that if a fine is to be paid, you have to pay it. When I was sued, I learned that the more you resist, the worse it ends up being. The world that I’d understood in childhood, the one my parents raised me in, the one where things made sense and actions had appropriate consequences, that world had been utterly destroyed by the time the “FBI” ever called me on that sunny day in San Francisco.

Because of these experiences, I felt that everything could be a threat. For years after this I lived in a state of fear. I remember telling my executive coach that I often felt like I was “waiting for the other shoe to drop.” So when the fake threat about owing back taxes appeared from the “FBI,” I saw it as real, and I wanted it to end. I had been vulnerable and targeted in the past and lost a lot. This time, I was scared, and I thought I knew what to do: just pay and move on with your life. It was a trauma response.

I wasn’t alone: in 2017, Indian police arrested a man who allegedly defrauded 15,000 Americans of millions of dollars, using the exact claims of “IRS back taxes” that caught me. Nearly half of all Americans have been subject to some kind of credit card fraud, amounting to $8 billion in aggregate, with cases rising since the pandemic began.

The thing is, and I understand this only now, I was in a state of panic. Because of what had happened to me in the past, when I got this phone call, I wanted an exit button to press, and it didn’t exist. So I panicked. It felt like anything I would do to resist would potentially create new problems and consequences that I wasn’t prepared to face. To me, paying was the path of least resistance, the way to wake up from the nightmare.

Recognizing that adverse events affect all of us in a different way, I tried to incorporate a variety of strategies into my resilience framework. Instead of telling everyone to “stand your ground no matter what” or “never give up, never give in”, I use more pragmatic suggestions like confront reality (part of Respond), or check in (part of Restore), which help you avoid that state of panic that might cause you to lay yourself at someone’s feet and unintentionally hurt yourself. Getting scammed taught me a valuable lesson in dealing with a crisis—there’s always time to pause, think, and share.

My Resilience Rules Framework

I realize now, too, that in that panic, my cognitive function shut down—which is what happens when you’re scared. I can’t blame myself for not thinking more clearly. When you’re facing a threat, your brain doesn’t have the same ability to function as it would when you’re safe, just as it can’t work the same way when you’re hungry as when you are fed. If I had been more aware of that then, I could have avoided reacting immediately, slept on it, and then reached out for help, knowing intellectually that my brain was not functioning well. If you’re panicking, you can’t think your way out of the problem. That “pause” can be the first step in the resilience framework. Most problems don’t snowball immediately; you usually have a little bit of time to assess and make a plan. Whenever you can, take the time you have before responding to a problem, and in that time you can reach out for help as well.

Processing those past experiences would certainly have helped me avoid this one. This also influenced the development of my resilience framework: if you’re going through a hard experience, and you let it happen, and you don’t understand and take the steps to take control of your life narrative, you continue to be victimized by those experiences. That’s why part of the resilience rules is to reflect—not just in the moment, but also afterwards, and to reach out to help from others—family, friends, a therapist or coach—to process experiences you don’t understand.

It’s akin to healing a physical injury. Why would you run on a sprained ankle? You’re going to put yourself in a position to hurt your other ankle, or your knee, and recovery just got that much harder. This is why we need to process trauma and hardship instead of burying it as soon as the active experience is over. Because the trauma from my experiences had fundamentally changed my worldview and sense of self, I was primed to buy into the phone call and believe that I needed to atone for some perceived wrongdoing. My trauma put me in a place of panic, and that panic blinded me to what was happening.

My wife grew up with a more cynical worldview than me. This makes her far less likely to get scammed like I did because she was warned by her parents to be skeptical of everything—that people are always out to get you. I’m more open to the potential of human goodness, and while she might be savvier than I am, sometimes I fear that she misses some of the goodness that I see. I don’t want these stories to change my fundamental nature. The resilience framework that comes out of these experiences is about how to face negative events and face change with, perhaps, an open palm instead of a closed fist.

Still, the most important thing I’ve learned about resilience I learned from my wife: what she wished more than anything wasn’t that I had made smarter choices, but that I had come to her with my problem. Telling your story, asking your questions, revealing your struggle—this is ultimately the most important part of resilience. It is almost never the wrong decision to share—even if it’s just a journal entry with yourself or a single trusted confidante. Let your secret lose its power, and let someone else in to help you carry the burden. They may even have the secret to banish the load.

This piece was written by Jason Shen, as told to Rachel Jepsen.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!