What does 1930s Iowa corn have to do with ChatGPT? More than you’d think. Lewis Kallow, a writer who partners with startup founders on content strategy, traces a through line from skeptical farmers to today’s fastest-growing AI products, revealing why great ideas get rejected and what finally makes them spread. His takeaway: In an age of commoditized code and saturated channels, understanding how trust travels through communities may be your last competitive edge.—Kate Lee

Join us tomorrow for a live, hands-on workshop with the team building Cursor, one of the most powerful AI coding tools available. Free for subscribers.

In 1933, the state of Iowa was facing catastrophe. Decades of outdated farming practices had left the state’s crops weak and vulnerable. Fifty percent of the year’s harvest was already rotting in the field due to a market crash, and severe dust storms were threatening to turn an economic disaster into a wholesale agricultural apocalypse.

Then, hope arrived: “hybrid corn,” a miraculous new seed capable of producing healthy crops that were easy to harvest and could thrive even in drought.

But after a year of expensive sales campaigns and educational pushes, officials were baffled. While 70 percent of Iowa’s farmers knew about hybrid corn, less than 1 percent had adopted this perfect solution.

“A man doesn’t just try anything new right away,” one farmer reasoned.

As insane as this example seems, rejection is in fact the norm for great, new ideas, even when people are aware of the benefits.

Take the seatbelt. By the mid-70s, 91 percent of U.S. drivers knew it saved lives, yet only 11 percent actually wore one.

AI may seem like the exception to this rule; ChatGPT exploded to 1 million users in just five days. But OpenAI had been trying to sell GPT 3.5 to executives for months with no success, and despite the model’s power, quarterly revenue was only $15 million.

ChatGPT succeeded because OpenAI finally understood sociology—the same sociology that was essential for the eventual adoption of hybrid corn, the seatbelt, and almost every great idea that eventually gained widespread popularity.

Recent research has cracked the code on what these sociological forces are. I’ll explain how these dynamics determine whether humans decide to embrace something new, how they relate to winning trust within a community, and how you can harness them to drive adoption for your own business.

AI has made it faster than ever to build and market products, and the channels we’ve long relied on are saturated. Harnessing the power of trust and community is the one of the last remaining ways for builders and creators to secure a competitive edge.

Executing an AI-first strategy with Box

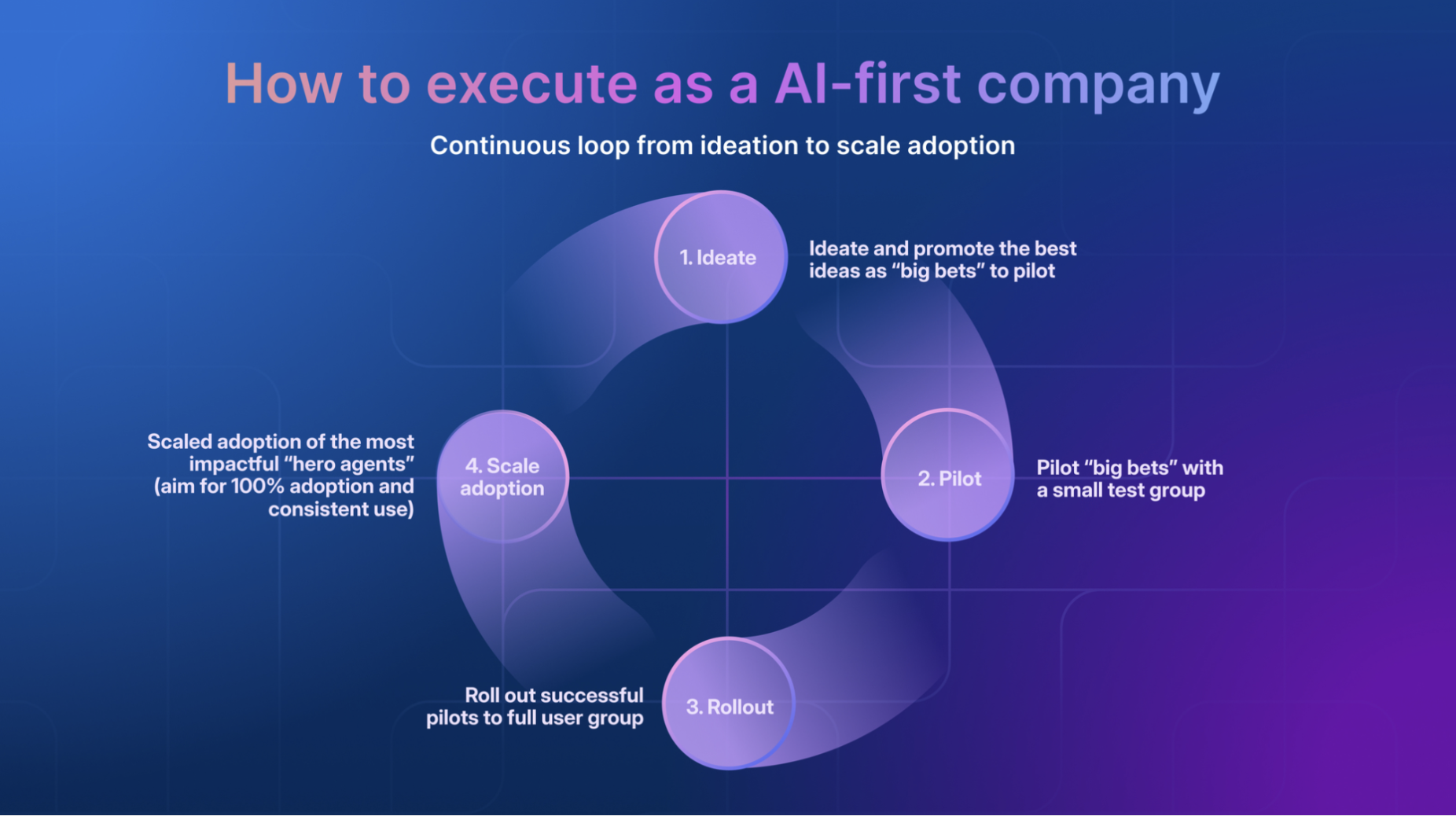

Box, the leading intelligent content management company, is breaking down how it structures experiments, frameworks for AI principles, and more in its “Executing AI-First” series. In it, you’ll discover how to turn a raw idea into a strategic AI powerhouse, and get a step-by-step playbook for empowering teams to thrive in the era of AI. You’ll learn:

- How Box approached becoming AI-first through its value realization strategy

- How to deploy agents with an Ideate>Pilot>Rollout>Scale plan

- How to identify and empower AI managers

- How to measure what matters by tracking AI agent impact

Dive into Box’s “Executing AI-First” series and follow along for actionable insights and downloadable templates.

Low risk is viral. High risk is social.

Iowa’s corn conundrum puzzled scientists for the better part of the 20th century, but a review published in Nature Communications in 2024 uncovered the secret after more than 90 years by doing a broad analysis of the research to that point.

“The key insight,” the researchers write, “lies in the fundamental distinction between simple and complex contagions.”

A simple contagion is defined by low risk. Think of a funny viral cat video—free to consume, easy to share, and socially safe. You only need to watch it once to decide to send it to your friend. When the risk is clearly low, “a single exposure to an agent can be sufficient for transmission to occur.”

Complex contagions, on the other hand, are ideas that “require individuals to make a substantial personal investment due to the costs or risks involved, including reputational or social risks, personal risks, and personal effort.” Will this expensive corn seed actually grow? Is this new software worth the time to learn? Will I look foolish for wearing this seatbelt?

When the risk of adoption is high, a single recommendation is rarely enough to move us; we need social reinforcement—to see others using it—before we decide to take the plunge. This explains Iowa’s farmers: They were reluctant to embrace this risky new idea after a single visit from a salesperson, because no other farmers in their trusted network were recommending it. They weren’t ignorant; they were cautious.

We embrace complex contagions based on norms, not knowledge. So where do you find an environment in which people can be exposed to your new idea by multiple different others?

Density before distribution

This was the challenge that the founders of Airbnb faced in 2008.

Despite receiving national news coverage for a viral cereal box stunt, the site was making $800 in revenue per month. The founders were contemplating giving up. After all, if no one uses your product after national news coverage, will they ever?

Staying in a stranger’s house is a risky behavior that defied the social norms of the day—the perfect example of a complex contagion. One news broadcast was not enough to convince people.

So they flew to New York City to meet around 30 hosts in person. The founders took them for beers, 10 people at a time, and stayed in touch after returning to California. They turned those few users into evangelists, and Airbnb finally took off.

These beer meetings created the specific network structure required for a complex contagion to spread. Social scientists call these structures “wide bridges.”

A wide bridge is where you have multiple points of interaction with a complex contagion—you hear about it from several different contacts. The more contacts who recommend something, the wider the bridge.

These bridges are widest inside tight-knit communities where individuals have a large number of overlapping mutual connections. If you can convince even a small subsection of a narrow community to adopt your idea—whether it’s an office, an online forum, or a pickleball club—then a magical cascade can unfold. As your small subsection pings other members multiple times about the new idea, they gradually convert each member until they take over the whole group.

This pattern extends to the most advanced technology of our time.

One hundred and thirty-five thousand people visited ChatGPT on its launch day. They weren’t random internet users. They were AI safety researchers, Silicon Valley developers, and machine learning experts who had been following OpenAI’s progress for a long time. These groups had spent years forming wide bridges in passionate physical and online communities. The people who initially propelled ChatGPT to millions by the end of the first week were embedded in remarkably fertile networks.

This is exactly how many of the biggest winners in AI have emerged. Midjourney didn’t launch with a Superbowl ad; the company started on a Discord server. The CEO of Jasper AI, an early winner in AI-powered marketing, admitted that the company’s primary growth strategy was posting templates in a Facebook group for marketers. Meeting transcription tool Granola started by targeting venture capitalists.

This is the same mechanism that solved our hybrid corn conundrum. Farmers didn’t adopt the seed because a scientist told them to; they adopted it once they saw their trusted neighbors succeed with it (who those early adopters were exactly will be revealed shortly).

The sociology of complex contagions is the dark matter of product adoption. It all hinges on community, and finding the right individuals in those communities to become champions of a new, daring idea or technology, which brings us to three questions:

- Which community should you target?

- Who within that community should you approach first?

- How do you convince them to take the risk?

Let’s tackle each of those one by one.

1. Which community should you target?

If complex contagions require wide bridges to cross, then your first job is to find the right canyon to span.

Some founders know their community from the start.

When a consultant asked Strava co-founder Mark Gainey to describe his target audience, Gainey pointed to a nearby table at the cafe where they were: four cyclists in tight Lycra outfits sipping espressos after a ride.

The consultant’s eyes widened. “When I ask entrepreneurs that question, nine out of 10 times they point to everybody in the Starbucks,” she said. “They say, ‘The great news is that anybody is a target.’ What you just told me is that it’s those four people, and you can go have a conversation with them and really understand their needs.”

These were what Gainey termed “MAMILs” (Middle-Aged Men In Lycra)—a narrow subsection of the passionate “top third” of athletes who loved having access to data about their performance using tools such as smart watches.

Instead of spending money on advertising, the founders met the MAMILs in their habitat: cycling races. They stood at the finish line and helped them upload their data to Strava. In doing so, the team learned that cyclists wanted to know if they were faster than their friends up specific hills. That insight led to the invention of Segments and Leaderboards, two quintessential features on Strava to this day.

By targeting the MAMILs, Gainey created a dense, interconnected cluster where the signal could bounce back and forth, creating the wide bridge necessary for the behavior to stick and spread—for trust to travel.

You won’t always find the right community on the first try. Pinterest’s founders initially courted the Silicon Valley tech crowd before realizing their true wide bridge was Midwestern female craft bloggers. The founders of Character.ai were taken by surprise when their platform was overrun by passionate fandom communities. You won’t always pick the right canyon first, but specificity is the only way to anchor a bridge.

Once you have identified your community, you face a second, critical question: Who within that community should you talk to first?

2. Who do you approach?

Our instinct is usually to look for the person with the most status, the president of the homeowners’ association or the most popular person in the room. Iowa proves this instinct wrong.

Researchers of the hybrid corn study wanted to know what made the early adopters special. Was it their personality, their financial situation, or perhaps their social standing?

They found a significant difference between those who embraced hybrid corn early versus later, but it wasn’t what you might expect. Being a “leader” in the community—someone who held office in a local organization—had no relationship to being a leader in adopting the new corn seed.

The researchers found that the fastest adopters were decades younger than the most resistant, better educated, and read more. But the biggest difference was in their social habits. The fast adopters simply showed up in more places, more often. They belonged to three times as many organizations, took more trips to the “big city” (Des Moines), and were more likely to attend movies, athletic events, and other recreation. They were the most active participants in their community.

This suggests that the people we want to connect with first are those who are most receptive to new ideas and most socially active—a finding that is still being replicated to this day.

A 2016 study from researchers at Princeton, Rutgers, and Yale universities showed the same dynamics in the spread of social norms in 56 New Jersey middle schools. Specifically, they wanted to spread an idea notoriously unpopular with early teens: that bullying and conflict aren’t “cool” anymore.

Half of the schools were designated as a control group and went about their year as usual. In the other half, the researchers selected a “seed group” of 20 to 32 students in each school to become the public face against bullying by designing posters, creating hashtags, and handing out wristbands.

The results were impressive. In the schools with the seed groups, disciplinary reports for peer conflict dropped by an average of 30 percent. Some seed groups were more successful than others, and the success depended almost entirely on who was in it. They were not the most popular; rather, they were the ones who self-reported to have spent time with the highest number of other people. Like our early adopting farmers, they were the most socially active—the ones present in the most social interactions.

We can think of these people as “social dandelions.” Just as a dandelion is one of the most common and widely seen flowers, these students and farmers are the ones who are most present and visible to the most different people across the entire social ecosystem. In schools where the seed group had the highest proportion of social dandelions, the program reduced bullying by 60 percent—double the average.

This phenomenon played a pivotal role in the rise of one of the fastest-growing business software companies in history: Slack.

When Slack launched, it faced the classic “empty room” problem. A messaging app is only useful if everyone uses it, but no one wants to use it if they are the only one there. The typical solution to this problem is to sell to the CEO or the CIO and have them mandate the software.

But Slack realized that this approach often leads to zombie accounts—software that is purchased but never adopted. The company recognized that a large company is effectively a bundle of distinct communities—where the engineering team, the sales floor, and the marketing department all function as their own independent tribes. Their more sociologically savvy strategy was to target one of those communities at a time, ignite a fire there, and let it spread.

They chose engineering teams as their starting point. Why? Because in a modern software company, engineers are the “corporate dandelions.” They sit at the intersection of the org chart, constantly interacting with product managers about features, designers about user interface, and marketers about launch timelines. If you can get the engineers talking, you eventually get everyone talking.

Slack went even further and targeted a smaller subset of engineers: ”internal champions.”

As senior experience architect Min Young Lee defined it, they are the “visible point people who connect with colleagues on an empathetic level and can convince them that change is worth the hassle.” (Emphasis mine.)

When Slack scours an organization for these champions, they look for “informal leaders” who have the ”dedication” to show up—those who have the “time to participate” and “let others know of their role and availability”; who “represent the general user” rather than the executive suite; and who possess a “wide network” to spread the message.

Whether you call them dandelions or champions, the premise is the same: To spread a complex idea, you first need to win over the most socially present individuals. But even if you find the right community and identify the right dandelion within it, you still have one final hurdle to clear.

Even the most enthusiastic champion can’t spread an idea if the adoption cost is too high.

3. How do you convince them?

There is one final force that can kill your idea dead in its tracks: effort.

When OpenAI released GPT-3.5, the model was technically capable of almost everything ChatGPT can do today. But the simplest way to use it at the time was in the OpenAI Playground, a developer interface cluttered with intimidating settings such as “temperature” and “frequency penalties.” Worse, you had to carefully word your requests to get good results, and if you wanted it to chat like a helpful assistant, you had to set that up yourself.

But then OpenAI abstracted away the confusing technical settings, wrote the perfect prompt for the system, and packaged the same intelligence in a chat window that made it feel like texting a friend. The AI didn’t change, but the wrapper did. (Many commentators seemed to forget that ChatGPT was one of the original “AI wrapper” products—it was the final ingredient required to tip AI into the mainstream.)

This tactical removal of friction is everywhere in the AI landscape:

- AI image generator Midjourney launched directly inside Discord, an app millions already used. By making generations public, they allowed new users to learn by copying experts, lowering the adoption cost from “mastering complex parameters like --ar 16:9 alone” to “copying your peers.”

- AI code editor Cursor made AI-powered coding more easily accessible by putting an end to copy-pasting, allowing developers to review and accept changes directly in their files, and packaging it inside an interface they were already comfortable with using every day.

- AI meeting transcription tool Granola realized the biggest barrier to recording meetings wasn’t technical. It was the social awkwardness of a bot joining the call and announcing it was recording. By recording the audio directly from your computer, Granola remains invisible to the other party. They lowered the adoption cost from “apologizing for a bot” to “zero.”

From code to community

The code is a commodity. The distribution channels are saturated. As we move deeper into the age of AI, the bottleneck for success has shifted. It is no longer about who can build the best technology or buy the most ads.

The bottleneck is now sociology.

The founders and creators who will define the next generation are those who understand the invisible physics of how groups of people decide to trust something new. They are the ones who know how to identify a narrow community, spot the social dandelions within it, and lower the cost of adoption until saying “yes” feels like the most natural thing in the world.

These sociological skills are fast becoming one of the few remaining edges available to us. And unlike code or copy, AI cannot generate them for you.

Thanks to Eleanor Warnock for editorial support.

Lewis Kallow is the author of The Action Digest newsletter and a ghostwriter for industry-leading founders. He is currently developing a consumer AI product and can be reached via X or LinkedIn.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora. Dictate effortlessly with Monologue.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies

. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

For sponsorship opportunities, reach out to [email protected].

Help us scale the only subscription you need to stay at the edge of AI. Explore open roles at Every.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

very insightful!! offering some inspirations for me as a student majoring in social science to find my position in this AI era.

@yijialoveemma thanks for your feedback and good luck with your studies!