Learn to Write with AI

Every is hosting a live two-hour workshop on using AI for digital writing on March 1. You'll learn how to use AI as a creative tool to help you do the best writing of your life.

Curious? Become a subscriber and RSVP:

You know what it’s like when you’re in the zone at work: On some days, work feels easy, enjoyable, and satisfying. You move easily from task to task, challenges are fun to solve, and you have a sense of clarity that you’re working on exactly the right things.

Yet the same work on a different day can feel like a tedious, difficult grind. Each task feels like a burden, you keep getting distracted, and your incessant inner monologue criticizes everything you do.

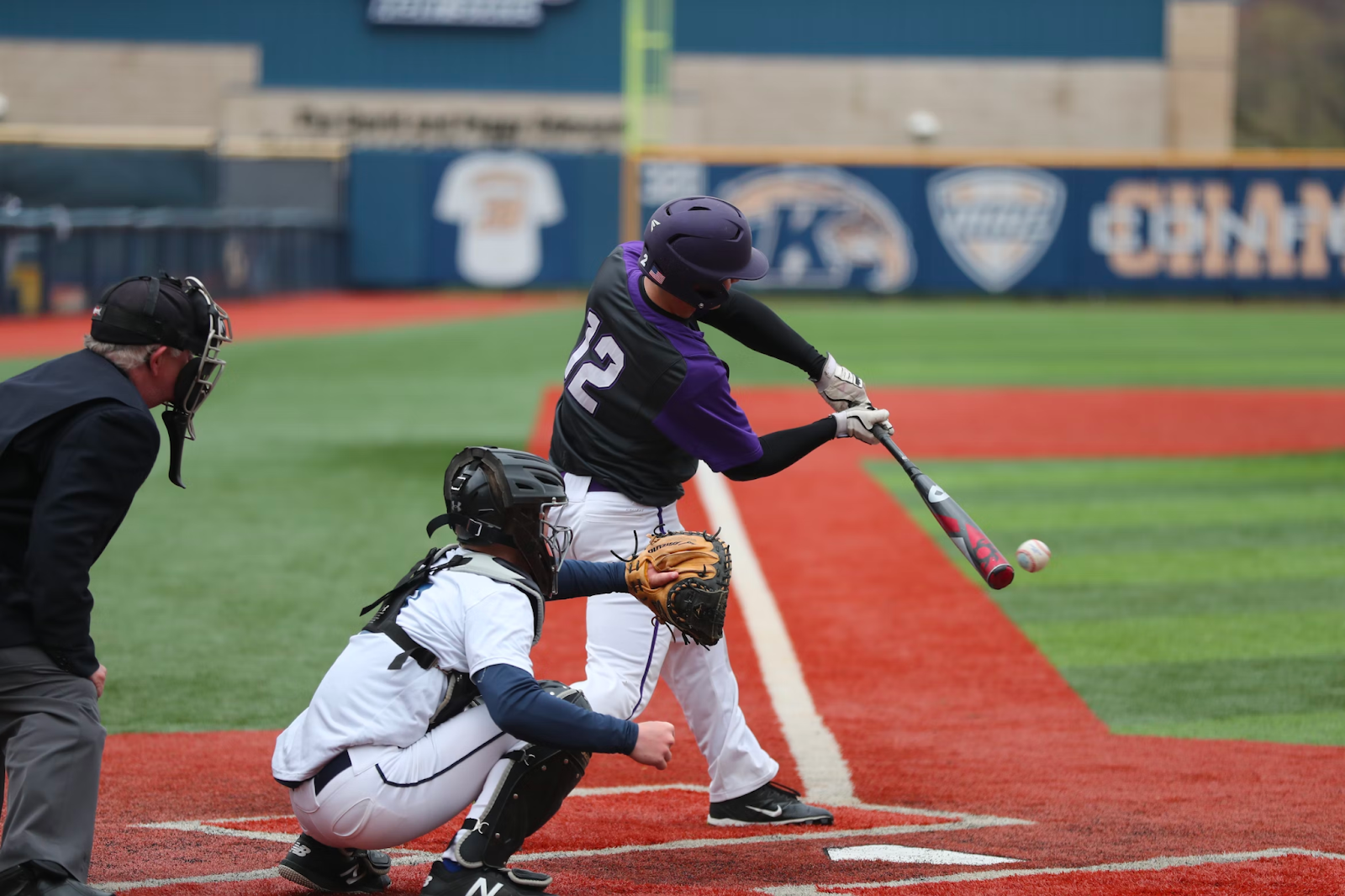

This phenomenon is similar to the experience of “choking” in a sports context. A baseball player might be on a great hitting streak when all of a sudden they lose their magic. They get caught up in their heads, trying harder and harder to get back whatever they had. But the more they try, the more anxious they get, and their performance continues to suffer.

In short, they have the capacity to access enormous skill and potential, but they get in their own way. The same process can show up for you while you’re working.

I’m going to explore perspectives and tools that will help inspire more of those easy days and fewer of the debilitating ones, drawing inspiration from W. Timothy Gallwey’s book The Inner Game of Work and from my own knowledge of the Alexander Technique, a kind of mindfulness practice that’s integrated into daily life.

It starts with noticing, and being more intentional about, what you’re paying attention to.

Focus affects your body and mind

Let’s play a game to illustrate the power of your focus.

First, notice somewhere in your body that catches your attention—do this before reading on. Keep noticing all the sensations from this place, like pressure, tension, and how good it feels.

Did your attention go somewhere that feels unpleasant—uncomfortable, tight, or painful—like your lower back, neck, or shoulders? If so, this is a common tendency. When I run this exercise in groups, most people report that the first thing they notice is discomfort. Even this small insight is telling: When left to its own devices, your mind may tend to orient toward pain or on problems that need solving, be they physical, mental, emotional, or anything else. While it’s an enormously useful function—we wouldn’t be where we are as a species without it—it may cause you to dwell on the negative more than is constructive.

Pick somewhere else in your body that feels uncomfortable. Keep noticing this place as you read this sentence, pause for a moment, and then notice the rest of your body. What has happened to your posture, your breathing, and the tension in your face and jaw? Many people report more generalized muscle tension, less natural movement in their bodies, and shallower even strained breathing. What about your thoughts and mood? Do you feel down? What would it be like to work like this?

Give yourself a quick shake, take a deep breath with a slow exhale, and let your attention drift to a new place in your body, somewhere that feels light, easy, and pleasant. It might be somewhere you don’t often notice, like a finger, a toe, or your tongue. Rest your attention in this new spot and let your body and mind respond, as if you’re being directed by this light and easy experience. Noticing the rest of your body again, how are your posture, breathing, and tension in your face and jaw? Many people report greater ease, slower breathing, more positive thoughts, and an enhanced mood.

Keep moving your attention between tight and easy places in your body and see what happens to the rest of your experience, both as you read the rest of this piece and throughout your day.

This effect—that what you pay attention to affects your mind and body more broadly—goes beyond noticing just positive and negative sensations in your body. Let’s look at some other things you might focus on that are relevant to work—and where they come from.

The two selves

In The Inner Game of Work, a sequel to his book The Inner Game of Tennis, Gallwey introduces two distinct parts of us, which he calls Self 1 and Self 2.

While coaching tennis players, Gallwey realized that most players were having an internal conversation with themselves that sounded like highly critical coaching: “Get your racket back early. Step into the ball. Follow through at the shoulders.” This was usually followed by a judgmental and negative evaluation of their performance: “That was a terrible shot! You have the worst backhand I’ve ever seen!”

When this exchange is viewed between coach and player, it makes some sense, although we might consider the coach harsh if they spoke to a client this way. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised if you had some teachers who communicated like this, or even your parents or other caregivers at times.

But what’s happening when this exchange takes place entirely within your own head? Who is giving these commands and judgments—and to whom?

Gallwey called the voice giving commands and judgments “Self 1” and the one receiving them “Self 2.” Self 1 is the internalized voice of the parent, the teacher, the critic—maybe even of the culture itself. It’s the voice that says, “Do this, don’t do that, be better at this, be afraid of that.” Most people have some understanding of Self 1, although many seem to fully identify with it and call it simply “me.”

Self 2 is the one that takes action in the world, like swinging the tennis racket, writing the report, or giving the presentation. Unlike the critical Self 1, the silent Self 2 is always present. As Gallwey puts it: “In my definition, Self 2 is the human being itself. It embodies all the inherent potential we were born with, including all capacities. It is the self we enjoyed as young children.” If you consider all the muscle movements and careful timing involved in hitting a ball moving through space, it becomes clear that you have no conscious idea how you do any of it—it seems to happen by itself. That’s Self 2.

Gallwey noticed in his tennis coaching that a player’s performance was superior—easier, more elegant, and more accurate—when the drill sergeant-like voice of Self 1 quieted down and allowed Self 2 to do its thing. Performance improved when internal interference in players’ natural mechanisms was reduced, which Gallwey summarized as performance = potential – interference. The aim is to allow the full potential of Self 2 to express itself not by trying to, but by minimizing interference from Self 1 and then just staying out of the way.

This isn’t as simple as it sounds, because there’s a trap. Self 1 is usually clever enough to realize what needs to happen but doesn’t have access to the right “move.” It knows that it needs to stop giving commands and issuing judgments, but the only way it can do so is by giving commands and judgments, which only compounds self-interference. The result is meta-narration, like, “I really just need to stop being so hard on myself,” which causes its own problems.

Nonjudgmental awareness is curative

The way out of this trap is achieved not by trying harder to fight Self 1, but by paying attention to the world in a curious, nonjudgmental way.

In each moment there is an array of things that you could focus on. For example, as I’m writing this essay, I notice that I have 15 minutes left of this pomodoro session. Here’s where I risk activating my Self 1. It might say that I’m not working quickly enough, I have other important things to do, or I’m not articulating my point clearly enough. These are all judgments.

Instead, I can take a step back, zoom out, and decide to notice the time as though it’s a factual, objective statement about the world: “There are 15 minutes left on the timer. How interesting.”

To convey the level of distance I’m instituting, I often advise my coaching clients to observe themselves and the world as if they are an alien anthropologist from the future. This alien doesn’t have any emotional investment in how quickly I write this essay. It doesn’t flinch when it sees the time. It just keeps a log of what’s happening in the world it’s exploring.

This kind of nonjudgmental awareness, Gallwey says, is itself curative. Awareness of the situation is enough to resolve problems, at least when it comes to our inner workings. The different roles of Self 1 and Self 2 are at the root of the effectiveness of awareness. Self 1 doesn’t do anything besides give orders and issue judgments—Self 2 swings the tennis racket. When Self 2 receives information about the task at hand, it takes action to resolve it. Layering on judgments about the problem and urging yourself to try harder to fix it interferes with Self 2’s capacity to do so.

Focus on critical variables

Nonjudgmental awareness is necessary to quiet the voice of Self 1, but you can also direct your focus toward factors that will help your Self 2 work as smoothly as possible. Gallwey calls these “critical variables.”

Critical variables are important things you could pay attention to that are relevant, even if indirectly, to the task at hand. Gallwey uses the example of driving a car, where the desired outcome is to get safely from A to B. You would pay attention to both external things—like the car’s speed, position, and the weather—and internal things, like your attitude, any distractions, and your own level of comfort. In a work context, critical variables might include your mental attitude, the intended outcomes of your work, how long a task is taking, or alternative choices you could make.

In the book, Gallwey talks about an experiment run with telephone operators in a customer service team within AT&T. These roles were important because they had exposure to customers; they were also stressful because they were fast-paced and closely monitored, and customers were often irritated. And the roles were boring because there was little new to learn beyond the initial training.

An intervention was developed to reduce operators’ stress and boredom while increasing their enjoyment on the job, but included nothing about directly improving customer satisfaction. The operators were asked to note the qualities they observed in their customers’ voices, like warmth, friendliness, or irritation. They were also trained to modulate these qualities in their own voices so they could respond with a greater range.

By choosing to focus on critical variables in the tones of customers and their own voices, operators’ stress and boredom decreased while their enjoyment increased. At the same time, reported customer satisfaction went up, even though nothing about the intervention aimed for this outcome. Performance improved because the operators were having more fun and trying less consciously to do a good job. Self 2 was allowed to perform without interference from Self 1, so the operators naturally performed better at responding to customer needs and were less easily upset by irritated callers.

Part of my own practice of this technique is to notice how much fun I’m having while engaged in an activity. This doesn’t mean that I am trying to have fun. I just tune into the physical and mental sensations and notice how strong, or absent, they are. If the voice of Self 1 says such things as “I should be having more fun” or “Why would you expect work to be fun?” my nonjudgmental alien anthropologist makes a note of that. My Self 2 can then naturally orient toward fun without my Self 1 interfering with it.

Unlocking Self 2 in your own life

If you want to access the easy focus of Self 2 in your own life, here is a guide to get you started.

First, place a reminder in a prominent place where you’re exploring this, like a sticky note on your screen. This may seem unnecessary, but one of the most challenging aspects of any mindfulness practice is remembering to do it in the first place. It’s easy to get caught up in the inner world of Self 1 and forget that you wanted to start noticing things differently.

Unwinding the interference that Self 1 creates requires you to notice it in a nonjudgmental way. Whenever you catch yourself ordering yourself around or judging your own performance, smile and think, “Ah, there goes Self 1 again,” or something similar. By bringing this level of nonjudgmental noticing to the existence of Self 1, you’ll naturally get more distance from it, and you’ll start to identify with it less.

Next, bring a relaxed focus to the critical variables involved in whatever it is that you’re doing. What factors are an important part of your work that, if improved, will lead to a better outcome? For example:

- How long does a particular task take?

- How aligned is a task with the project’s objectives?

- How are you using the available resources to achieve the outcome?

- How engaged are the people you’re working with?

- How engaged do you feel while working?

The answers to these questions shouldn’t be complex or difficult to answer. It can be as simple as writing down the time after a work session or noticing your own mood as you work—and all of it with an attitude of “Oh look, how interesting.” If you flinch at what you notice, notice the flinch and carry on.

As you settle into Self 2, widen your focus to see what else you notice, because other critical variables—like your level of enjoyment, the attitudes of others, or what you’re learning—may start to emerge. Part of Self 2’s capabilities is to bring relevant variables into conscious awareness, or as Gallwey puts it: “Self 2 is the inherent intelligence behind our selection of what to attend to.” The more you play with the ideas in this essay, the more you’ll come to trust that Self 2 knows what it’s doing without Self 1 bossing it around.

Finally, watch out for urges to change anything you notice about the critical variables, because this is where Self 1 sneaks back in. For example, if you see that you’re taking longer to finish a piece of work than you expected, and you experience fear, doubt, or self-judgment, gently notice it and decline any pressure you may feel to try to work faster—because this will just bring in interference from Self 1. Instead, bring other critical variables into your awareness, stay in that nonjudgmental space, and allow Self 2 to do the work with the ease that only it can provide.

Michael Ashcroft is a teacher of the Alexander Technique, coach, and writer with a background in energy technology innovation. You can read more of his work at michaelashcroft.org and expandingawareness.org.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!