Sponsored By: Sunsama

This essay is brought to you by Sunsama, your personal assistant for deep work.

All entrepreneurs want to know how to win. Investors all want to know how to pick winners. The issue is that no one can really agree how to do either.

Depending on who you talk to, you’ll hear different gospels espoused. Some are devotees of the cult of the founder. For such an adherent, there are entire publications all devoted to the study of successful people.

Simultaneously, there are those who prefer the magic of ⭐frameworks⭐. Their divine prophets are thinkers like Clayton Christensen and Michael Porter. This kind of thinking makes sense to me! Surely there is a “right way” to build a billion dollar company.

For many years, I felt like I was just on the cusp of understanding the secret. I was an archaeologist, digging through hundreds of books—company profiles, strategy theory, biographies of founders—to find the buried treasure of truth. I religiously read all the newsletters people told me to subscribe to, listened to the podcasts by all the greats, and tried to understand the “why” behind the headlines. I was driven by this deep hunger to understand.

Now, ~10 years into this journey, I have started to form a new thesis that runs somewhat contrary to existing methods of evaluation.

I would propose that the secret to building a successful technology company is culture-market fit. Culture-market fit (CMF) is that blissful intersection of an opportunity in the market with a culture that can execute on said opportunity. Allow me to clarify: CMF occurs when an organization matches with an opportunity, and the organization’s culture allows the right strategies and process to occur allowing them to capture said opportunity. Sometimes that will mean giving employees lots of freedom (Google), and sometimes that will mean micro-managing people (Amazon), but the important thing is that the culture cultivated correctly addresses the market opportunity. A company’s culture is a vibe, an ethos, that permeates every slide deck, every product decision, every analysis. When there is no clear right answer (which is always) the culture-market fit is what drives decisions.

Logging into work on Monday mornings can be overwhelming: as soon as you open your computer you are bombarded by Slack messages, e-mails, calendar invites, and work-related notifications.

Sunsama is here to change that. Thousands of ambitious professionals use it every day to get a focused view of everything they need to accomplish each day across every tool they use from Notion to Asana.

Stay focused, and end burnout with Sunsama:

Culture-market fit does not mean that the organization is hyper-aligned with customer interests, either. CMF is determined by crafting the internal culture that wins the external market. Sometimes that is aligned with customers, but sometimes it is also done through more…company-oriented decisions. Exxon and Chevron and nearly every Big Bank regularly screw over their customers but are still fiscally successful over an extended period. Some companies are motivated by ethos, some by greed, some by hubris, but all winners match their culture and incentives to the market they are serving. A market opportunity is where a business can extract the most long-term profits, not necessarily the one that gives customers the goods or services they would most prefer. Empowered founders are important and so are strategy planning sessions, but they are all cultural outputs.

If I am correct, then this framing has important implications for capital deployment inside of organizations and in which startups are best for funding. I want to emphasize something: I recognize how pie-in-the-sky, non-numeric this idea is. It is not as intellectually soothing as a perfectly crafted chart or spreadsheet. However, I’m increasingly convinced that businesses are made in the ugly, daily, poorly illuminated decisions. In those times, it isn’t spreadsheets that wins—it’s culture-market fit.

TL;DR

- Culture-market fit is more important than product-market fit because it precludes any product decision

- Culture is the deep understanding of your customers, the people you hire to serve those customers, and the approach those individuals use to serve customers

- Having CMF means that your organization’s design, product, and operating mandate match the market opportunity

Culture-market fit > Product-market fit

For every successful deployment of a strategy theory working or a founder archetype succeeding, I can find an equally successful strategy or founder taking the exact opposite approach. This conundrum is at the heart of the problem.

Take product-market fit, for example. If you were to ask 50 people what product-market fit is you would get 50 different answers. As with everything in startup linguistics, it is more handwavy than definitionally firm. Roughly speaking, it is when the product you have made resonates deeply with the customers you are targeting. This resonance can manifest itself in accelerated revenue growth, customer demand, etc.

Allow me to offer 3 examples of PMF, all of which took entirely different paths to get there:

- Figma (acquired for ~$20B) spent 4 years building their product before publicly launching. Product was made via a whiteboard session.

- The Apple 1 came to be almost magically. Wozniak said that after attending a hobbyist computer club meeting “this whole vision of a personal computer just popped into my head.” Within a few months, he completed the prototype entirely on his own. Jobs sold 50 of those computers before he even had made anything more than a prototype.

- Superhuman (an email client) took 3 years before the founder would believe that they had product-market fit. Interestingly he said, “We found pockets of PMF with specific segments of founders, managers, executives and business development professionals. Once we recognized this, we were able to focus the entire company on serving that narrow segment better than anybody else.”

These stories are compelling to me because they all represent radically different methods of building winners. Figma was a turtle, hiding in its shell while it tinkered. Apple, a stroke of genius. Superhuman, a steady grind upwards. Every startup success story has a point of PMF, but all of them took a different path to get there. PMF matters but it is the output, not the input of success.

Additionally, ask yourself—when did Facebook achieve product market fit? There have been so many moments where the company stared death in the face and decided to double down. Was PMF achieved when they went from Hot or Not to Facebook? When they launched the newsfeed? Or maybe it was Sheryl Sandberg expanding the ad product? International expansion? The switch to mobile? The Instagram acquisition? All of these moves were somewhat data-driven but ultimately came down to something more instinctual. This same questions can be asked of Microsoft—was it Windows? Office? Xbox? Azure?

Even when a company achieves initial product-market fit there are a litany of things that can kill it. In those moments of danger, an executive will perform an analysis but a clear consensus is unlikely. It is rare that the answer is obvious. But even in the circumstances where the answer is obvious, the winner of the market share race will be the one who best executes on the opportunity.

The secret ingredient in all these circumstances is something deeper and more mysterious: what I’m calling culture market-fit.

Culture-market fit examples

After I left Substack, I had so many people ask me what made the company different. Why was it successful when there were so many failed tech companies that tried to serve writers? The answer is simple: they were the first competitor in their market that had writers in their DNA. Whether it was refusing to call their sales motion a sales team (writers typically hate being sold things) or starting most discussions with some variation of “What you are reading?”, they worked really hard to ensure that a writer ethos permeated the company. The team understood what made writers tick and simultaneously identified a gap in the market that their product could fill. The intellectually lazy way to describe this is customer obsession, but it's more nuanced than that.

When discussing the products we create, we usually classify them in terms of problems. The thinking is that customers hire a product to accomplish a job, which is sorta true. Of course people want products to do a certain thing for them, but there are all these layers of social signaling and implied cultural understanding that go into the purchase experience. Let’s compare two seemingly simple examples.

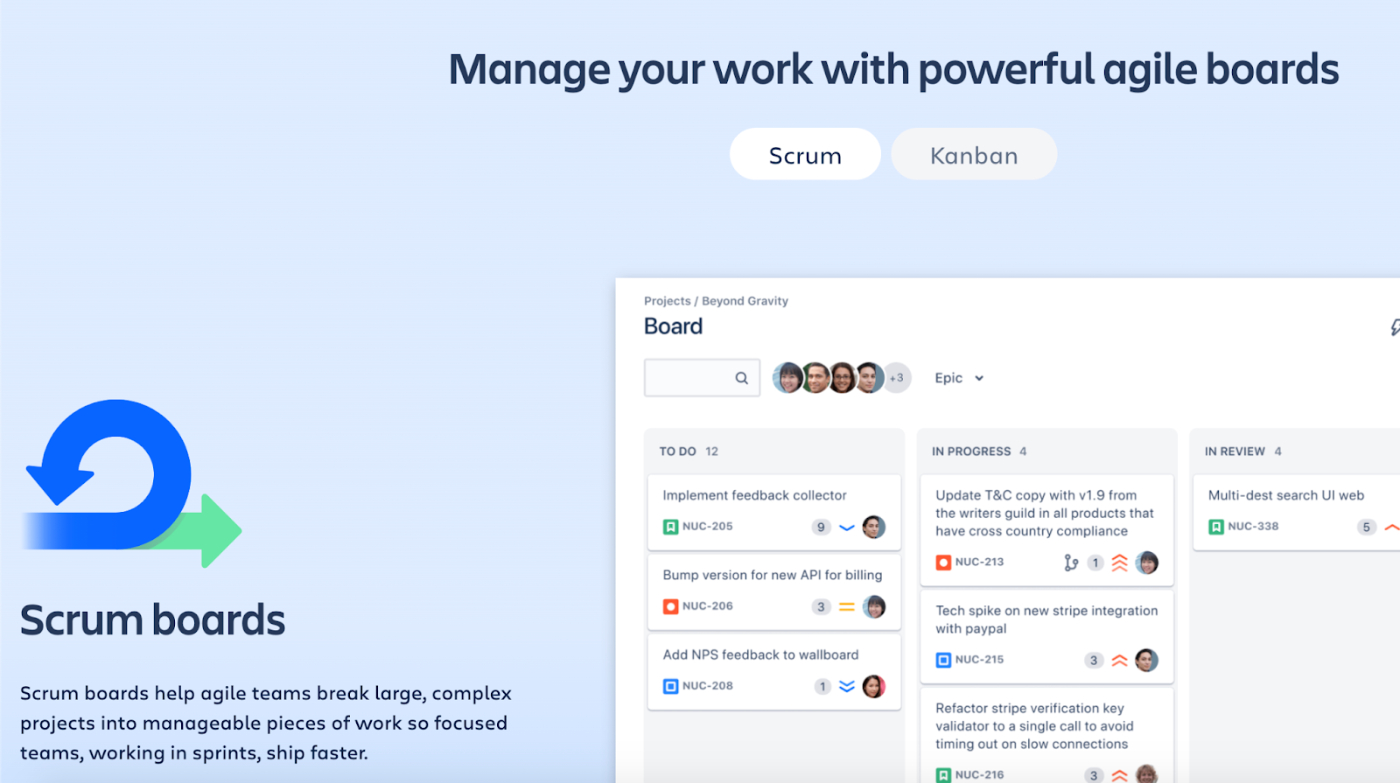

Software engineers have pretty much been stuck to Jira for tracking their development process forever. The landing page for Jira looks like this:

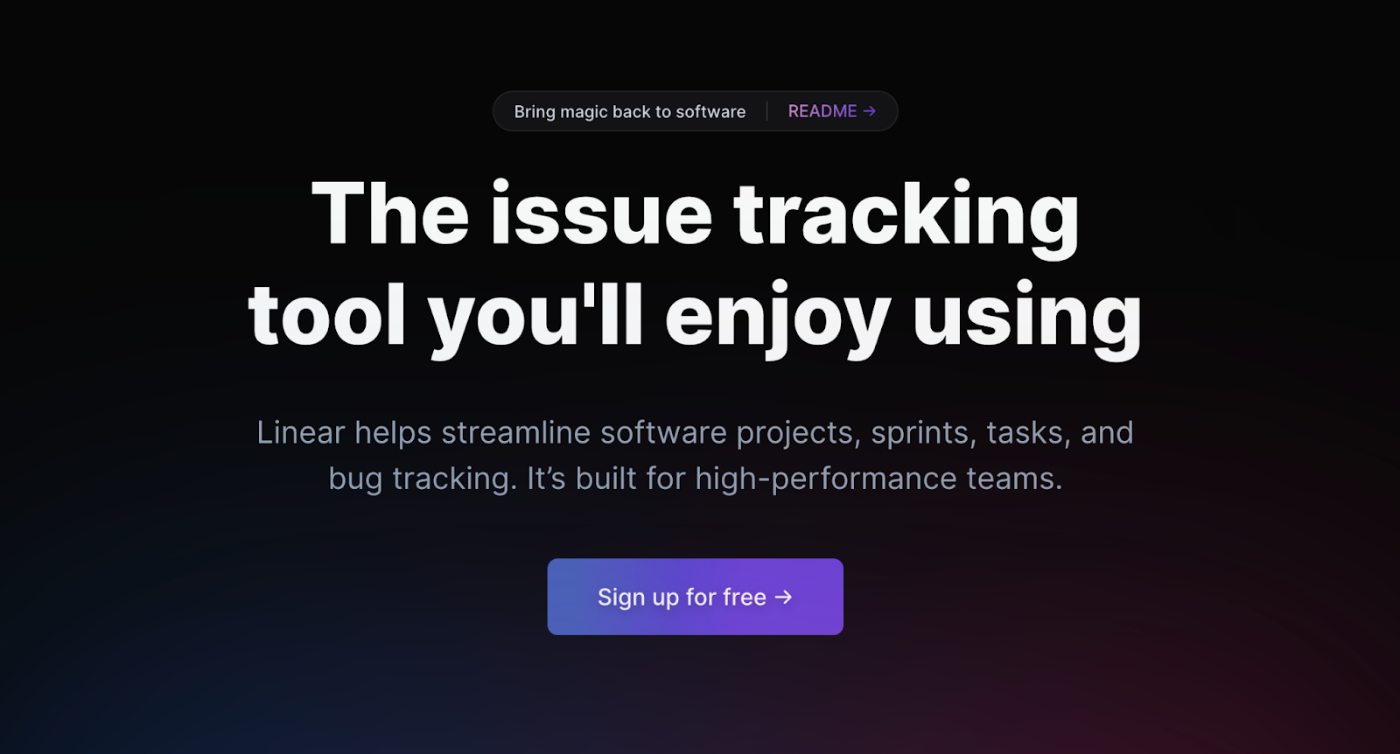

Generic, semi-boring, but usable. Compare it to this from Linear, a Jira competitor I like.

As you scroll down the page there are fun animations that only a software developer would notice. The page is in dark mode and gets straight to the point. They point you towards an essay espousing the magic of software.

I am not saying that Linear’s approach is the best way to approach landing pages. Most companies would be better off with the Jira approach. However, Linear knows exactly who they are serving and puts in all these signals to developers that resonate with them. It is the same story with what features they display. Linear focuses on the things that matter for their customers: speed, hotkeys, and dark mode.

Jira talks about project management methodologies (yuck).

Keep in mind this is for some of the most boring use cases on the planet! Even B2B software has these ethos baked in.

This manifests itself in staffing too. Linear’s team is built, from top to bottom, with people who come from top-shelf engineering cultures. Jira has a random assortment of people, who I am sure are wonderful, but don’t match similar obsessions and pedigree.

Culture-market fit also occurs in cases where the team has little in common with their customers, but they just have the right personalities to win the market. Case in point is Uber. There was absolutely nothing original about Uber’s strategy. Lyft did peer-to-peer rideshares first. Doordash and Grubhub popularized gig economy food delivery. Even autonomous driving was first done by Google. Nothing at Uber was wholly original. However, the market did not reward originality or alignment! It rewarded cruelty, malice, and a will to dominate the market. Travis Kalinck built an organization that incubated sexism and sometimes behaved despicably. He also built the fastest growing startup ever. There was a match between the product they built and the open space in the market. Note: There are many great people at Uber, but I don’t think the characterization of the company as a hard-charging and rough place is unfair.

Culture-market fit in practice

Let’s say you buy the idea that the secret to growing a business is CMF. How do you predict it? How do you measure it?

Culture-market fit is signified by two things happening simultaneously:

- An organization has an operational set of ethos that determines how decisions are made and incentivized

- That ethos puts the correct executives and strategies in place

To correctly measure CMF, it is easiest to work backwards from step 2. The most obvious sign of CMF is retroactive. If X company is already a fiscal success then clearly they already have CMF. The more interesting question is how to measure CMF before there are other signs of success. This is where you see the cult of the founder and the cult of the framework wage their ideological battle. These conflicts are ultimately fights between methods of pattern recognition. If you are a strategist who has seen a certain vein of startups succeed, you’ll get a sense of how these feel and be able to invest accordingly.

I’ve always loved the story of Masa investing in Alibaba as an example of this. From an article I wrote in December of last year,

“When Jack Ma pitched Masayoshi Son in 2000 for an investment in his fledgling ecommerce site Alibaba, “He had no business plan, zero revenue,” Son said in a later interview. “But his eyes were very strong. I could tell from the way he talked, he has charisma, he has leadership.” This is very clearly a stupid investment thesis. Saying you got lost in someone’s eyes and gave them 20 million dollars would cause most limited partners to panic. Despite the dumbness, or perhaps because of it, that investment returned 4,500% when Alibaba went public at a $90B valuation. The stake ballooned up to $150B in value at one point—not bad for simply swimming in the depths of Jack Ma’s irises.”

The practice of building and investing in businesses is learning all of the frameworks, studying all the founders, and learning when to disregard all of those previous lessons. This is part of the reason why young founders can sometimes generate outsized results—they don’t know what they don’t know and stumble through blind luck/genius into a novel opportunity.

An organization searching to create CMF has to evaluate what type of cultural personality will win the market. There’s only so much you can learn in the abstract because cultures can’t be learned the same way you can learn a specific fact or skill, they have to be participated in and absorbed. There is a magic feeling that happens with CMF. The task is to see if you can capture it.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!