PepsiCo — the $180 billion conglomerate that owns a wide assortment of food and drink brands — is feeling the coronavirus recession. People aren't buying their products in restaurants. They're not buying them in movie theaters. Same thing at stadiums, bars, and airports. Q2 is not looking great.

And so, to make up for it, they’re starting a startup. The goal is to sell snacks online, and just this week, they launched two new websites: Snacks.com and PantryShop.com.

These might not seem like a big deal, but actually it’s a huge step in PepsiCo’s larger plan to own the relationship with their customers. They’re capitalizing on the current environment to accelerate the timeline.

“But wait,” you might say, “Why would they want to start a DTC startup? I thought DTC startups that sell low-value items like snacks usually had terrible margins?”

Usually, you’d be right. But PepsiCo has some unique advantages that other startups don't have, which might make this a good idea for them. To assess their strategy, let’s first explain how these new websites work, then compare them to what DTC startups typically do, and finally explore how PepsiCo can avoid the problems DTC startups usually face.

How PepsiCo’s new websites work

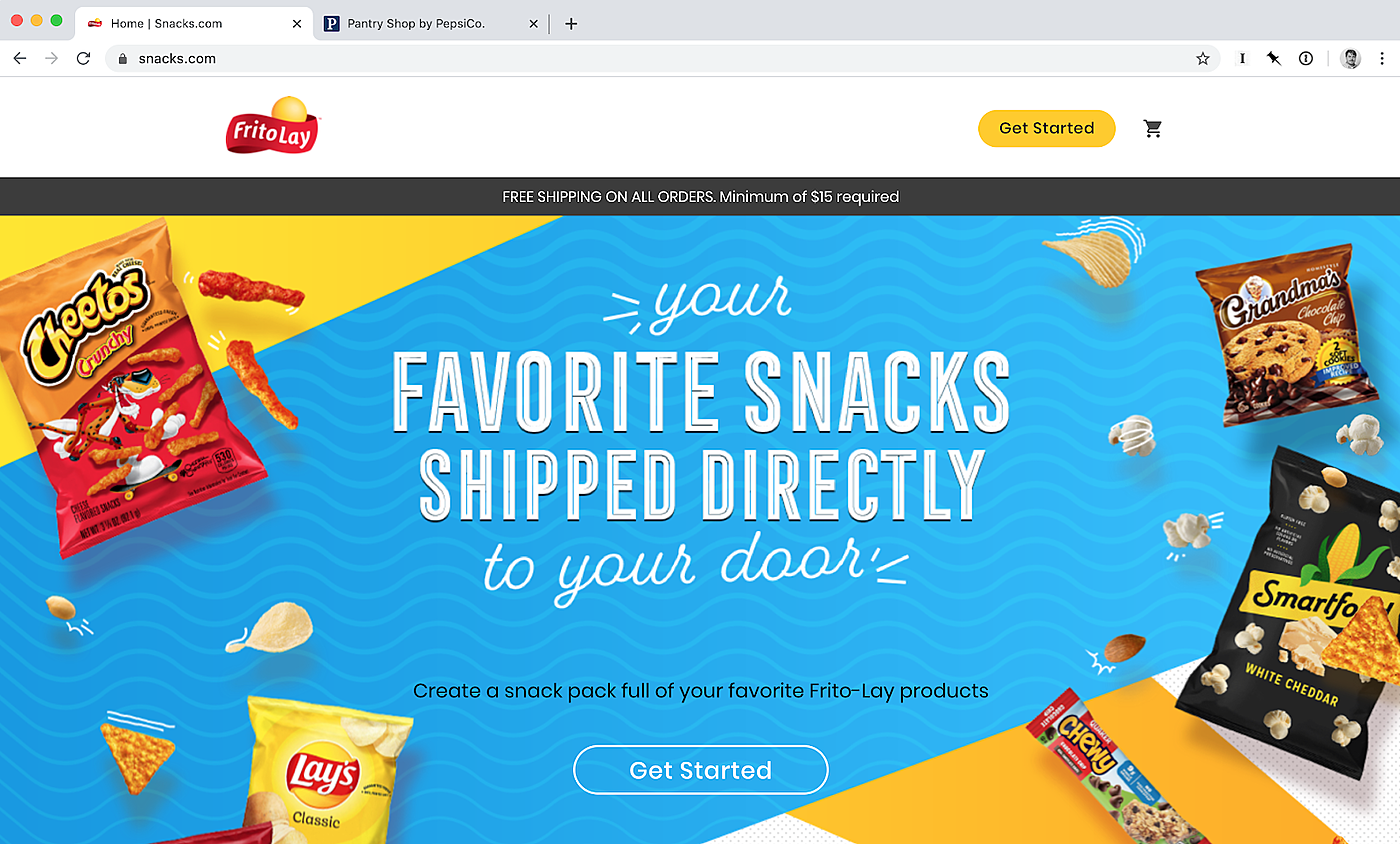

At Snacks.com, customers can select from over 100 Frito-Lay branded products (such as Lay's and Cheetos) to fill a “snack pack,” with free shipping on orders over $15.

Fun fact: PepsiCo has owned the “snacks.com” domain for over two decades, and spun up the website in 30 days because of the quarantine.

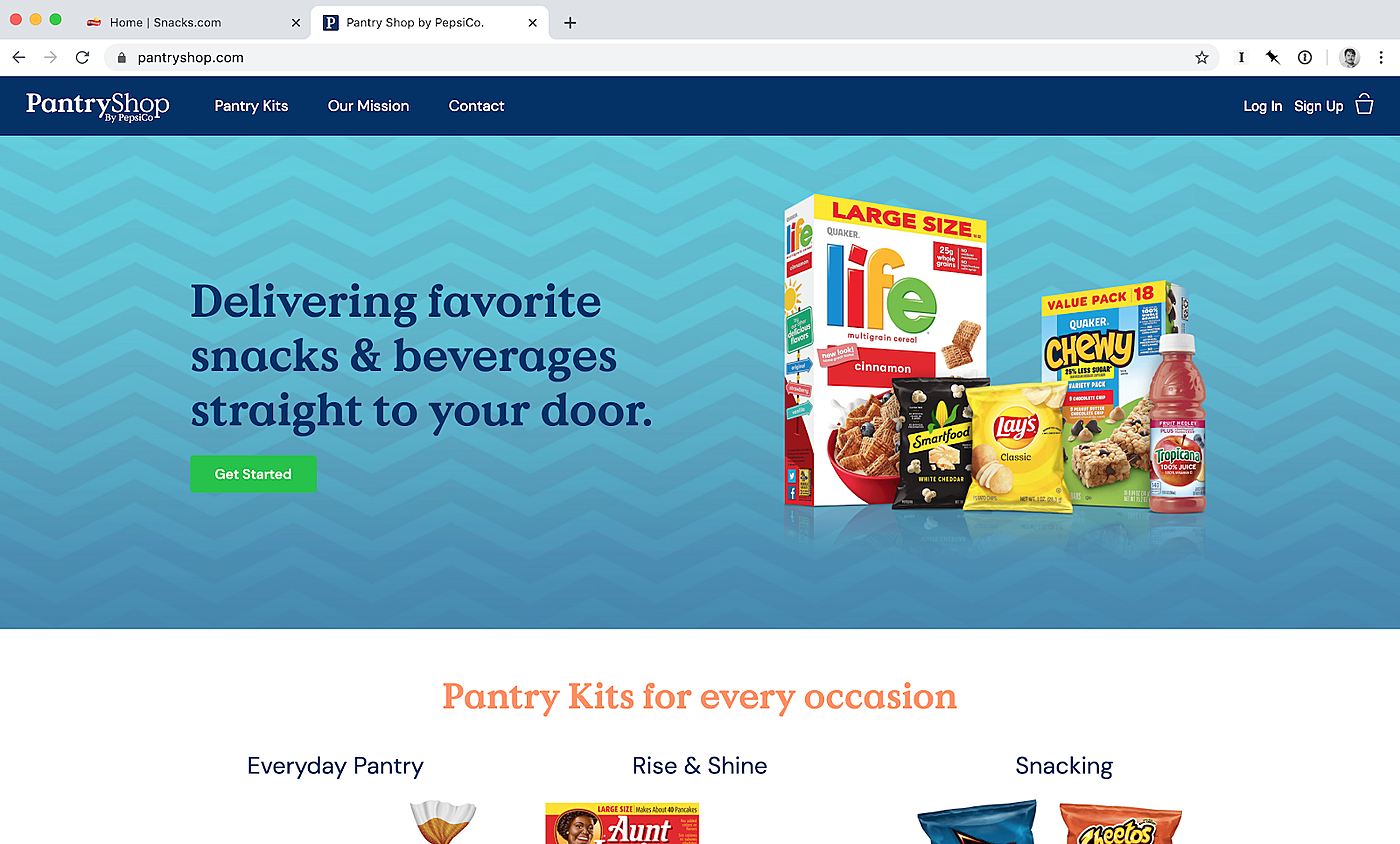

PantryShop.com sells specialized bundles of products centered around a category. For example, they have a bundle called "Rise & Shine" which includes Quaker oatmeal, Tropicana juice and Aunt Jemima pancake mix.

You might be wondering why they bothered to build these as two sites instead of one. And it’s a good question. I guess they have some theory that it’ll be easier to market them if they’re targeted to a very specific “job to be done.” But honestly, it doesn’t feel intuitive to me.

But let’s take a step back. Overall, was it a smart move to build these websites?

We think yes.

Why DTC startups often struggle with gross margins

Most DTC food & beverage startups have a cold start problem.

People don’t want to buy a giant box of food they’re unfamiliar with. I mean, what if you don’t like it? But if you try to ship one product at a time, you’ll get crushed by fulfillment costs. An 8 oz bag of chips might be priced at three or four dollars, but the packaging and shipping expenses will more than double the price. If you try to sell a bag of chips for $8 that people can get at the grocery store for $3, nobody will buy it.

So there’s a double-bind.* You can either force customers to buy in bulk (and discourage new customers from trying your product), or you can let people buy a single serving, and either eat the fulfillment cost and lose money, or pass it on to customers and lose sales.

*A “double-bind” is basically a type of trade-off, except all paths suck.

The best way around this problem is to find a way to generate high average order values (AOV). This way, the fulfillment cost is a much smaller percentage of the total sale. The idea is that when you're spending $100 on a big purchase, you don't notice the $4 shipping charge as much. It also gives brands room to offer “free” shipping and hide it in the overall item price.

This is why almost all successful DTC startups have emerged from categories that either naturally have high AOV (Warby Parker, Casper, Allbirds) or bundle low-priced consumables together to increase their AOV (Hello Fresh, BarkBox, Iris Nova).

Food DTC startups struggle with this. They’ll often resort to tactics like handing out samples at trade shows, and negotiating with grocery buyers to earn coveted in-store shelf placements.

And these hacks can sometimes work, but it causes them to miss out on the benefits of launching their products on the internet: customer data, rapid iteration, and having a direct relationship with their customers.

Basically, there’s a lot of friction holding these businesses back from their potential.

PepsiCo’s Advantage

PepsiCo avoids these problems because of two things: their vast distribution network and their expansive portfolio of established brands.

PepsiCo is uniquely able to offer fast and cost effective shipping because of their distribution infrastructure. They have one of the largest warehouse footprints, and they claim that they’ll be able to deliver a majority of orders in two days or less. Pretty good, if they can pull it off!

Additionally, through their vast portfolio of well-known brands, PepsiCo can nudge customers towards high order values. PantryShop.com sells seven bundles of three to six products each for $29.95 or $49.95. Snacks.com sells over 100 products (250 by the end of the month) and includes free shipping for orders over $15. This high AOV is key to solving the fulfillment cost problem that most DTC food startups face.

So yeah, we think this is a smart move. It might seem boring, but when you’re a multinational conglomerate, boring profitability is much better than interesting failures. Selling their regular products on the internet is a lot smarter strategy than other companies that have tried to be overly fancy about it.

For example, part of Nike’s recent success comes from doubling down on simple, boring DTC. They started investing in eCommerce in 2006 and hired an ex-eBay CEO to run the business. They invested in making their website a seamless experience and used the data to inform their retail strategy. Now almost a third of their revenue comes from DTC.

Their competitor Under Armour, on the other hand, spent over $700m purchasing three fitness apps and tried to move into a new category: connected fitness. It was a brand new business model (subscriptions & advertising) and introduced technology to an apparel company. Fancy! But growth in the “connected fitness” segment slowed shortly after the acquisition, and it’s one of the reasons Under Armour’s stock has fallen since their IPO.

Nike vs Under Armour is not a perfect analogy for the market PepsiCo is in, but it's wise to remember that multi-billion dollar public companies aren't great at taking the kind of risky bets that venture capitalists take.

Instead, they juice every penny they can out of existing products, and that’s exactly what PepsiCo is doing. They have the brand marketing. They have the fulfillment network. They have the products. It’s much easier for them to add another way for customers to buy their stuff than to create new stuff for customers to buy.

First contact

These new websites also offer something new for Pepsi: the chance to collect data on consumer behavior.

Until now, PepsiCo has had little opportunity to directly observe customers. But now, if this website gains steam, they’ll be able to make contact with their customers in a way that’s never been possible before.

They’ll be able to learn the answers to questions, like: What are customers putting in their carts, then abandoning before checkout? How much time are customers browsing certain product pages? What are those customers’ emails?

They can also use this data to run various marketing campaigns to customers. They can more easily upsell and resell. They can personalize emails and websites to maximize conversion. It might even be able to inform Pepsi on brick and mortar problems like their retail assortment and R&D roadmap.

For startups, this is table stakes. But for a big brand operating in the physical world, this customer data is a whole new world.

Who knows what they’ll be able to do with it?

Will it work?

It seems like it genuinely might work.

When you combine their distribution network with the loyalty and familiarity many people feel towards PepsiCo’s brands, it’s not crazy to imagine that a decent number of people may choose to purchase direct from the source on PepsiCo’s new websites.

On the other hand, buying stuff on the internet from a new provider is always a bit of a pain. You have to learn to trust it. You have to type in your credit card and address. In order to do this, there has to be a real incentive.

If you really want a dozen bags of Hot Cheetos, you can buy them on Amazon. The experience is nowhere near as polished as Snacks.com, but it’s the default. And that’s a challenging thing to compete with.

If PepsiCo’s new websites are to succeed, it won’t be because of a silver bullet. There isn’t one killer feature that will convince consumers to switch en masse. Instead, they’ll need a lot of lead bullets. They’ll need to execute extremely well on the basics like marketing, user experience, and customer service.

Whether a multinational conglomerate like PepsiCo is capable of doing that remains to be seen.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!