This is a chapter-by-chapter summary of Mastering The Market Cycle, a book written in 2016 by legendary investor Howard Marks. I’m reading this book in May 2022 because, for the first time in my career, the technology industry is entering a serious down cycle. As an entrepreneur there’s not a ton to do other than play it safe and try to remain profitable, but intellectually it’s interesting to me. And as an investor I would love to make the most of this time.

This obviously informs my agenda in reading this book, and will therefore shape the information I choose to highlight and what I choose to exclude. Specifically, I want to see if this book can help answer the following questions:

- How long is the current down cycle going to last?

- How far down will the market go?

- What causes down cycles?

Many people will tell you these questions are unanswerable. You hear it all the time: “it’s impossible to time the market and you shouldn’t try.” But this book basically argues that while you can’t predict with 100% certainty when the market is going to rise and fall, you can significantly improve your odds of making good investments with some sense of timing.

It might seem foolish, but Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Bill Gurley, and Ray Dalio all blurbed his book, and seem to think it’s smart. Plus, the proof is in the pudding: according to his Wikipedia page, Marks’ investments have averaged 19% compound annual return over the long run, which is pretty great. He attributes much of this to understanding what part of the market cycle he is in and adjusting his investment strategy accordingly.

So let’s go through each chapter of the book and summarize the main arguments. I’ll provide some of my own color commentary as we go along, too.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Why Study Cycles

- 2. The Nature of Cycles

- 3. The Regularity of Cycles

- 4. The Economic Cycle

- 5. Government Involvement with the Economic Cycle

- 6. The Cycle in Profits

- 7. The Pendulum of Investor Psychology

- 8. The Cycle in Attitudes Toward Risk

- 9. The Credit Cycle

- 10. The Distressed Debt Cycle

- 11. The Real Estate Cycle

- 12. Putting It All Together — The Market Cycle

- 13. How to Cope with Market Cycles

- 14. Cycle Positioning

- 15. Limits on Coping

- 16. The Cycle in Success

- 17. The Future of Cycles

- 18. The Essence of Cycles

- Afterword

Introduction

It’s useful for investors to understand how cycles work and to develop a sense for where we are in the current cycle, because it allows them to position their portfolio for what’s next.

Patterns are a natural part of nature. Some are easy to predict, like seasons and tides. Market cycles are harder to predict because they depend on human psychology. But if you pay close attention you can use them to your advantage, rather than suffer from the chaos they can cause.

Nathan’s Note:

- I wish he had more stories here of actual decisions he faced in his career and how he used his sense of cycle timing to make the call. Did he make bad calls in his career that were formative learning experiences? Were there any particular triumphs he’s most proud of? This is all very abstract and impersonal.

1. Why Study Cycles

Imagine a jar with 100 balls in it, some black and some white. Investing is like sticking your hand in the jar and betting what color you’re going to get.

If you don’t know anything about what’s inside the jar, you probably want to be fairly careful betting. But if you happen to know that there are 70 black balls and 30 white balls, then if you keep betting on black, you’re bound to make money over time—as long as someone is willing to take the other side of the bet.

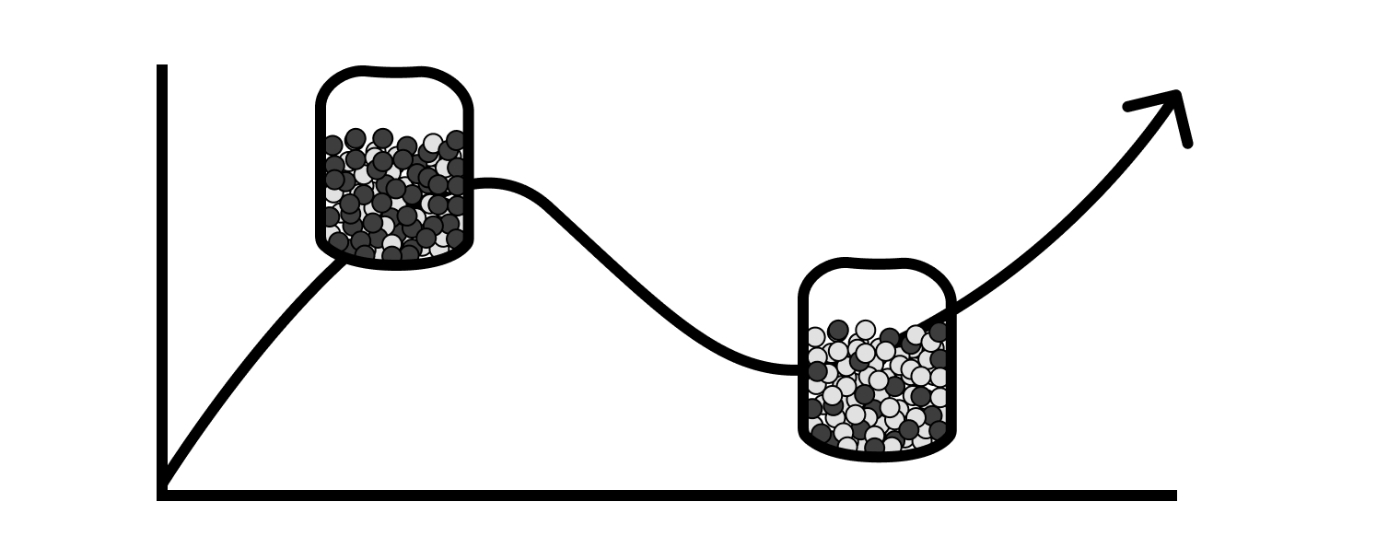

When markets are in a downcycle or upcycle, the jar is skewed in one direction or another. Investors are making bets regardless, but it is helpful to know the odds are stacked against them in some circumstances and towards them in others.

Just because you have improved odds doesn’t guarantee any particular outcome. But it does make it more likely, which is the best we can do while investing in an unknowable future.

The average investor doesn’t know much about cycles, hasn’t been around long enough to have significant personal experience with them, doesn’t read financial history to learn about them, and thus is adversely affected by cycles.

Nathan’s Notes:

- The interesting thing about investing is the balls you pull out of the jar aren’t just black or white binary outcomes—your investments sometimes can return 1000x or more, and sometimes go to zero.

- Of course the “1000x” style of investing is unique to early stage startups. Marks made his money on distressed debt, where you make a risky loan to a big company and charge interest rates somewhere between 5 and 10%.

- Perhaps market cycles matter less when you’re sticking your hand in a jar with 80% “go to zero” balls, 19% “modest return” balls, and 1% “return the fund” balls?

2. The Nature of Cycles

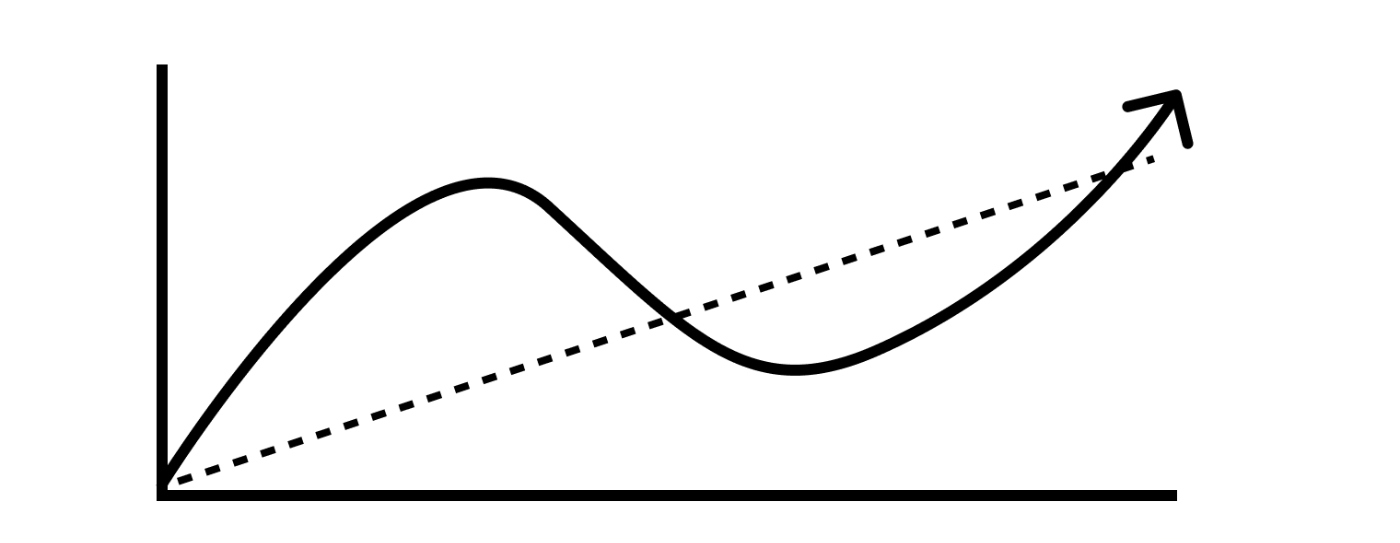

Market cycles revolve around some underlying secular trend, like GDP growth:

Cycles aren’t just a series of events that happen one after another. They are a chain of events linked by causality, where each causes the next, and is caused by what came before. Because the primary driver of ups and downs is overreaction in a positive or negative direction, which is based on human psychology, there will be no beginning or end to cycles.

Although the market cycle revolves around a midpoint, it doesn’t spend very much time there. Usually we are either in an upswing, where assets are overpriced, or a downswing, where assets are underpriced.

The further out we get above the midpoint, the more destructive the fall usually is. Some examples are the stock market crash of 1929, the flash crash of 1987, and the subprime loan bubble and financial crisis in 2008. More modest ups and downs are called “corrections”.

Sometimes, perhaps most of the time, the midpoint around which the cycle revolves is slanted upward. But there are significant differences between different situations. For example a fast-growing nation or industry will have a different shaped midpoint than a stagnant empire or aging conglomerate.

Nathan’s Notes:

- It’s fascinating how the market is constantly overreacting in a positive or negative direction, and very rarely underreacting or appropriately reacting.

- It makes sense because that’s generally what humans do: fixate on whatever information happens to be the most salient, and under-weight information outside our current frame.

- Curious if the idea of emotionally-driven market cycles is compatible with the efficient market hypothesis.

3. The Regularity of Cycles

Because cycles are driven primarily by fear and greed overreactions, it is hard to predict the duration of an upcycle or a downcycle. Millions of pieces of data and thousands of narratives combine chaotically to create human sentiment of financial decision makers.

But just because you can’t predict it exactly and just because the cycles are irregular doesn’t mean there is nothing to be learned about the subject. Even modest increases in odds can help significantly over time.

Nathan’s Notes:

- This chapter is frustrating because if you can’t know how long a cycle will last, it’s basically the same as not knowing where you are in a cycle, which means it’s highly questionable whether spending a lot of time thinking about it will actually help you improve your odds.

- I’m hoping this gets addressed in later chapters.

4. The Economic Cycle

Underlying the Market Cycle, which is driven by investors’ beliefs and expectations, is a somewhat less volatile system: the Economic Cycle. Some people also call this the Business Cycle. It is about real economic output, which is measured by GDP. The Market Cycle, by contrast, is measured by stock prices, interest rates, etc.

In the long run GDP tends to go up because it is a function of two variables that both themselves tend to go up over time: number of hours worked, and value of output produced per hour. The total number of hours worked increases as the population increases, and productivity per hour increases as technology advances. Of course, other factors like culture and government policy also make a big difference.

In the short run GDP can fluctuate based on many things. Some sectors might see huge growth based on new innovations. There can also be broad trends in consumer willingness to spend based on emotions like fear and joy.

When forecasting economic trends most people simply extrapolate from what’s currently happening. If the economy is growing, people tend to think it will keep growing. If we’re in a slowdown or recession, people assume things will get worse. But because those assumptions are widespread they tend to already be priced in, and difficult to profit off them. What’s valuable is to successfully forecast a diversion from the current trend. The trouble is, these predictions are usually wrong. And when they’re right it’s hard to know if it was just luck, or skill.

Nathan’s Notes:

- Marks doesn’t spend much time on it in this chapter, but the main thing that sticks out to me is how different industries and companies can be on different economic trajectories, and how important this is to understand.

- Like, the secular trend underlying growth of the internet is one of the most important phenomena in our lifetime to understand if you want to be a good investor, and it’s on a completely different trajectory than overall US GDP growth.

- It seems to me that it can be helpful to choose different levels of “zoom” for understanding the cycle risks any particular company faces: company economic cycle, industry economic cycle, country economic cycle, global economic cycle.

5. Government Involvement with the Economic Cycle

Because down-cycles are painful and up-cycles can lead to inflation (which ends up being painful), the government plays an active role in shaping the market cycle. It does so through two mechanisms: monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Monetary policy is set by the central bank: the Fed. They can buy or sell securities in order to make money more abundant or scarce in the financial system. Abundant money means cheap interest rates, more borrowing and spending, and has an overall stimulative effect. Scarce money means higher interest rates, less borrowing and spending, and often leads to down-cycles. (Nathan’s Note: I wrote about this in detail last week.)

Fiscal policy is set by all branches of government, and generally takes the form of increased spending (stimulus) during down-cycles. The original proponent of this sort of policy, Keynes, also proposed that during up-cycles the government could cool down the economy by running budget surpluses, but politicians pretty much never actually do that.

Nathan’s Note:

- It feels like Marks is holding out on us here. I would love to know how he incorporates this information practically into his investment decisions. Does he closely study the Fed? Does he talk to people who run big banks to get a sense of how interest rates might react to actions by the Fed? Come on, Mr. Marks. The people want to know!

6. The Cycle in Profits

Corporate profits are based on the economic cycle, but fluctuate more wildly. Some industries’ average profits follow the economic cycle closely (raw materials like metals and chemicals), others are mostly uncorrelated (haircuts), and others are inversely correlated (Costco memberships).

Businesses with high fixed costs and low variable costs will experience large swings in profitability based on changes in overall sales, while companies with low fixed costs and high variable costs will remain more or less equally profitable in good times or bad.

Also, businesses with high debt payment obligations tend to experience worse hits to profitability when revenue shrinks, as compared to companies financed mostly by equity investment.

There is a long tail of idiosyncratic events that also affect profitability: fads, wars, changes in technology, management blunders, management heroics, etc. These are complicated, but perhaps the most important is technology, which itself follows a lifecycle.

Nathan’s Notes:

- When I think about what determines a company’s profitability, I mostly think about how indispensable a role that company plays in the ecosystem. If counter-parties (customers, suppliers, etc) are easily able to go around the company without any issues, they won’t be very profitable. The opposite situation is basically the definition of “market power”.

- This is evaluated on a company-by-company basis, but market power is probably correlated across similar types of companies over time. For example major US automakers all experienced a decrease in market power as foriegn competitors gained ground in the US. Newspapers all over the world lost their power in the 2000s and 2010s.

- Perhaps part of tech’s current down-cycle is a narrative that many companies we thought had power and could easily get to profitability actually don’t, and can’t.

7. The Pendulum of Investor Psychology

Based on observations of the economic cycle, government influence on it, and resulting profits, investors form sentiments about the direction of the market. These sentiments are either dominated by fear or greed—the two opposing emotions are rarely in balance.

There are many pairs of opposite emotions that go along with each part of the cycle:

- optimism and pessimism

- euphoria and depression

- credulity and skepticism

Everyone feels these emotions, but the superior investor does their best to keep these emotions in balance at all times rather than swinging between one and another with the market.

When dominated by one set of emotions, information that fits the emotion is fixated on and information that doesn’t fit is ignored. Any room for interpretation tends to get skewed one way or another. Everything is capable of signaling either positive or negative outcomes.

Nathan’s Notes:

- In my experience this is extremely common knowledge. Of course, that doesn’t make it easy to put into practice in real life. The question is how?

- For me one of the most common and tempting mistakes is to be countercyclical “too soon”—which is the same as being wrong. If you insisted in 2015 that the market was too frothy and waited to invest, you’d have missed out on a 7-year bull run. The current correction we’re living through still isn’t enough to erase all those gains.

- Likewise, it’s obvious that we’re in a down-cycle at the moment (May 2022). But is now the right time to invest? The stock market could keep shrinking for years still. We just don’t know, and this chapter frustratingly doesn’t have much that helps us make the call.

8. The Cycle in Attitudes Towards Risk

Investing is basically bearing risk in pursuit of profit. The future is unknowable, but investing is about putting resources at stake based on the prediction that the future will unfold in a specific way. Therefore, how an investor manages risk is the primary determiner of their performance.

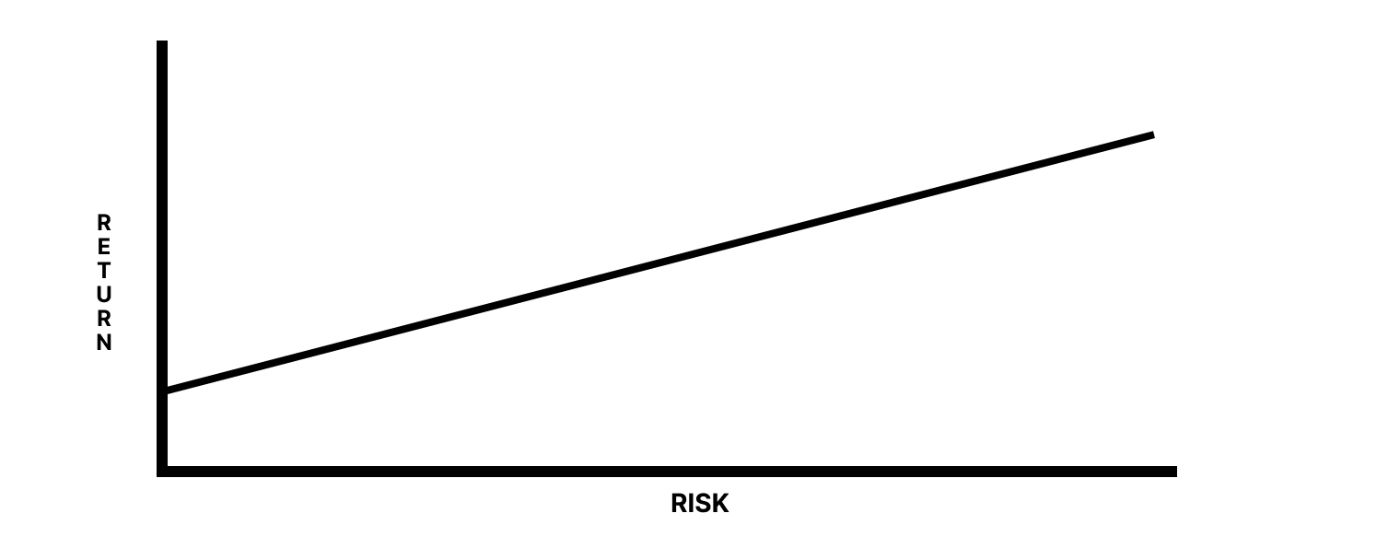

People say “high risk, high return” as if taking on more risk surely leads to greater returns, but this isn’t true. A better way of thinking about it is that investments that seem risky need to appear capable of producing high returns in order for anyone to want to make the bet, because people don’t like risk. This is why we see a positive correlation between risk and return.

In bull markets, people tend to become confident taking on a lot more risk, and the slope of the line flattens. This is exacerbated by the fact that investors need to compete with each other to stay in business, and it’s extremely difficult to decide to sit out a cycle when it seems like everyone else is making money. In order to stay in the market, they need to offer better and better terms, while taking on more and more risk.

Eventually it hits “the winner’s curse” where the investors winning deals end up in the worst positions. Once this becomes apparent, the market turns.

In bear markets, many investors refuse to bear any risk, which makes the rewards for those willing to do so abnormally high:

At this point in the book, Marks starts telling real stories from his actual experience investing, and it’s pure gold. There is too much rich detail to adequately summarize here, so if you’re interested you should buy the book and read this chapter. But I will leave you with the one that was most salient to me.

At the height of the subprime mortgage crisis Marks was in a tough situation with one of his investors where he was trying to get them to put in more capital so he could be in a good position if he got margin called, and as he described probable scenarios they kept asking “but what if it’s worse than that?” until it was fairly absurd. This conversation and the fear he detected was a primary signal to him that markets were irrationally risk averse, and now was a good time to take risk. He was unable to raise the needed capital from these investors so he put in the money personally, and it was one of the best investments he ever made.

The lesson? Skepticism is not the same as pessimism. When everyone is irrationally pessimistic, skeptical investors suspect there may be reason for optimism.

9. The Credit Cycle

Marks defines credit broadly as the ability of a company to raise money, in the form of debt or equity, to finance a business.

If the economic cycle is stable, and the profit cycle a bit less so, then the availability of credit swings wildly between “excessive” and “impossible” because of investor psychology and attitude toward risk discussed in previous chapters.

This is important to understand because the ability to grow is usually dependent on the availability of capital. When the credit window is shut, it can be difficult for many businesses to grow.

Anywhere you see a burst bubble, there is probably an overly permissive investor behind it. This happened with tech in 1999, real estate in 2007, and (Nathan’s Note) perhaps tech again in 2021.

The credit cycle is so important because it is capable of single-handedly driving the economy into a recession. This is what happened in the global financial crisis: there was no underlying economic cause, it was primarily created by a chain reaction inside the financial system.

Nathan’s Notes:

- In this chapter Marks also goes into significant detail about how the global financial crisis happened, and how at the bottom of the cycle forces were in place to cause a rebound.

10. The Distressed Debt Cycle

Marks is known for being one of the first large institutional investors to go into distressed debt. This is basically when you lend money to companies that are unlikely to repay it on time, and so the lenders end up with equity in the business. Their motto is “good company, bad balance sheet.”

Basically this is a specialized part of the credit cycle, described in the last chapter, that Marks has particular expertise in.

11. The Real Estate Cycle

Real estate has emotional up-cycles and down-cycles just like any other asset, but what makes it interesting and unique is the significant time lag involved in bringing new supply to market. Unlike issuing new debt or equity, it takes years in real estate between “let’s do it” and “the deal is done”, due to the difficulties in finding land, getting approvals, design, construction, etc.

Because of this, buildings that were initiated in up-cycles often reach the market in down-cycles, which makes the down-cycle even worse because new supply drives down prices even further. And then when things start heating up again, prices can skyrocket because it takes so long for new supply to be added.

12. Putting It All Together: The Market Cycle

(Note: I’m going to finish this in the next few days! I’ll include an update in my next email letting y’all know when it is done.)

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!