Two weeks ago I published my framework for doing market analysis, fusing the ideas of strategy legends Michael Porter, Clayton Christensen, and Hamilton Helmer. By far the most common request was to see a detailed example of how it works in practice. So today I have for you my analysis of the writing industry!

I picked this market because I’ve been working in the industry since 2015 (first with my startup Hardbound, then at Substack, and now Every) and at this point I know it fairly well. But I’m still learning every day, and in fact the process of doing this very analysis taught me a ton.

We’ll go through the following steps to figure out which businesses have sustainable market power in the writing industry, and why:

- Define the market. You can go as broad or narrow as you want, but what’s most important is that you nail down A) the job-to-be-done / use case, and B) the general product category that serves that use case.

- Identify the basis of competition. Why do consumers choose one product over another? What attributes are most important? Which are good enough, where no further improvement is felt? And which dimensions of product quality are felt to be lacking and in need of improvement?

- Map the value chain. What is the chain of activities that needs to be performed for raw resources to get translated into finished products? What companies are involved, and which activities do they control?

- Locate the position of power. Which activities in the value chain shape the end-user’s experience the most? These are the key activities that relate to the basis of competition. Which companies perform these activities? Who does it best?

- Trace the source of that power. Using Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers as our list of options (scale economies, network economies, counter-positioning, switching costs, branding, cornered resource, and process power) we’ll see which one has the biggest impact on the user experience, and therefore is the source of their power.

(If you want to learn more about this framework, read this.)

Ok, let’s get into it!

1. Defining “the writing industry”

For the purposes of this analysis, “the writing industry” is the group of businesses and people that perform the activities necessary to create articles and books.

Conventionally, most people would look at many of the fields I’m grouping together as separate, like the “newspaper industry” or the “book publishing industry” or the “magazine industry” or even the nascent “paid email newsletter industry.” But I am intentionally grouping them all together because it is my observation that most writers are willing to fluidly shift between formats depending on what is most lucrative, prestigious, and creatively interesting. And I think readers in most cases ultimately care most about the brain who created the words they love to spend time with, and care less whether they are seeing those words in print, on a kindle, or on their phone screen.

Of course there is no such thing as “the writing industry”—it’s a term I pretty much made up. But the redpill buddhist perspective is that all industry labels are ultimately just labels, but the labels and lines on the map are not the territory, and they can be useful or not depending on what you’re trying to do.

But I’m getting ahead of myself a bit. To get a truly useful industry definition, we need to nail down two things: the job-to-be-done we want to focus on, and the general product category. In this case the product category is simple: articles and books. But the job to be done is pretty complex.

Why do people read? What’s the job-to-be-done of writing? What problem does writing solve?

It’s an impossibly broad question, like asking what problem steel solves. You could say things like “steel’s job is to be a strong material with a bit of flexibility” or “writing’s job is to allow one person to receive stories, ideas, and information from another person in a way that is durable over time, easily compressed, scalably distributed, self-paced, and only requires one sense at a time (usually vision, sometimes hearing).”

This is an interesting rabbit-hole to go down, but it’s still way too broad. So let’s ask a slightly more narrow question: why do people read books and articles?

- To learn what is happening in parts of the world they care about

- To learn the history of things they care about

- To learn how a thing works, or how to do a thing

- To be entertained and absorbed in a story

- To wind down at the end of a long day

- Because a teacher made them

- Because a friend said it was good

- Because the cover at the bookstore caught their eye

- Because their friend (or enemy!) is mentioned in the article

- Because it reinforces a part of their identity they value

- Because the post went viral and they wanted to see what the fuss was about

Can we simplify this list any? I see two primary desires:

- Information

- Entertainment

Every written work has to have at least a little bit of both, in my opinion. And I’d actually go further and say that information and entertainment are two sides of the same coin. It is sort of weird to say, but I think when you feel entertained it’s the effect of certain arrangements of information.

As Marshall McLuhan said: “Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn't know the first thing about either.”

The reason comedy and romance novels and thrillers make us feel good (entertained) is because they arrange information in ways that activate certain centers of primal importance. Like, I think we like thrillers for the same reason we so often dream about scary or violent scenarios: they prepare us to survive in similar situations. And I think given the evolutionary importance of reproduction it should be obvious why romance and sex are so central to all forms of entertainment. Similarly, the best textbooks and academic papers feel incredibly entertaining to the right people, like they are unlocking the secrets of the universe.

Of course, doing this in a way that actually works and doesn’t feel cliché or dull is an incredibly difficult task. Great writing is rare. Which leads us to a very important problem inherent in the writing industry that the whole industry is structured around solving.

2. The basis of competition

The vast majority of writing you encounter is not going to contain any information or entertainment value that matters to you at all, but a lot of writing you encounter seems on the outside like it could be interesting. You can’t judge a book by its cover, but we have to decide based on something! It’s not like buying a poster, where you can assess the quality instantly just by looking. With writing you have to read it to know if it’s any good, but the cost of your energy and time makes it prohibitively expensive to do so. Therefore, we rely heavily on signals like who recommended it or where we saw it show up to assess if a written work is worth our time.

(An interesting aside: this problem is much worse with books than it is with essays, and much worse with essays than it is with news articles. With news, usually the headline tells you 90% of what you need to know, and the rest is elaboration.)

So a huge percentage of what makes writing successful comes down to establishing trust in a large audience that it’s going to be worth it. There are many different ways of doing this, but pretty much the whole industry revolves around this problem. Hence, it is the basis of competition.

- Newspapers try to establish credibility that their reporting is accurate

- Books get blurbed by famous people and authors go on talk shows

- Authors build brands around specific expertise in a specific subject matter, and when they stray from the genre it doesn’t go as well.

- Magazines have dominant editors that shape every creative decision in every story to fit a specific vibe

- Academics need to recruit more famous academics to vouch for their work

To really see how this works in practice, it helps to consider the past few books and articles you’ve read. How did you find them? What about them attracted your attention? How did you know they would be good? Were you right?

When you walk through the stories in your mind, another big part of the basis of competition becomes supremely important: distribution. You can’t read a book or article that you’ve never heard about in the first place! This is why bookstores were so important for so long, and why newspapers were much more profitable when they had expensive distribution monopolies in local metropolitan areas.

When you combine both forces from above, you get pretty good explanations for things that have happened recently in writing, like newsletters and Twitter threads. Newsletters are great because you own a direct relationship with your readers, who will probably like your next article if they liked your previous one. Twitter threads are great for reaching new readers, because a lot of people are on Twitter and you could go viral in a way that doesn’t really happen with web articles like it used to.

Once you understand this, it might help you predict what could come next.

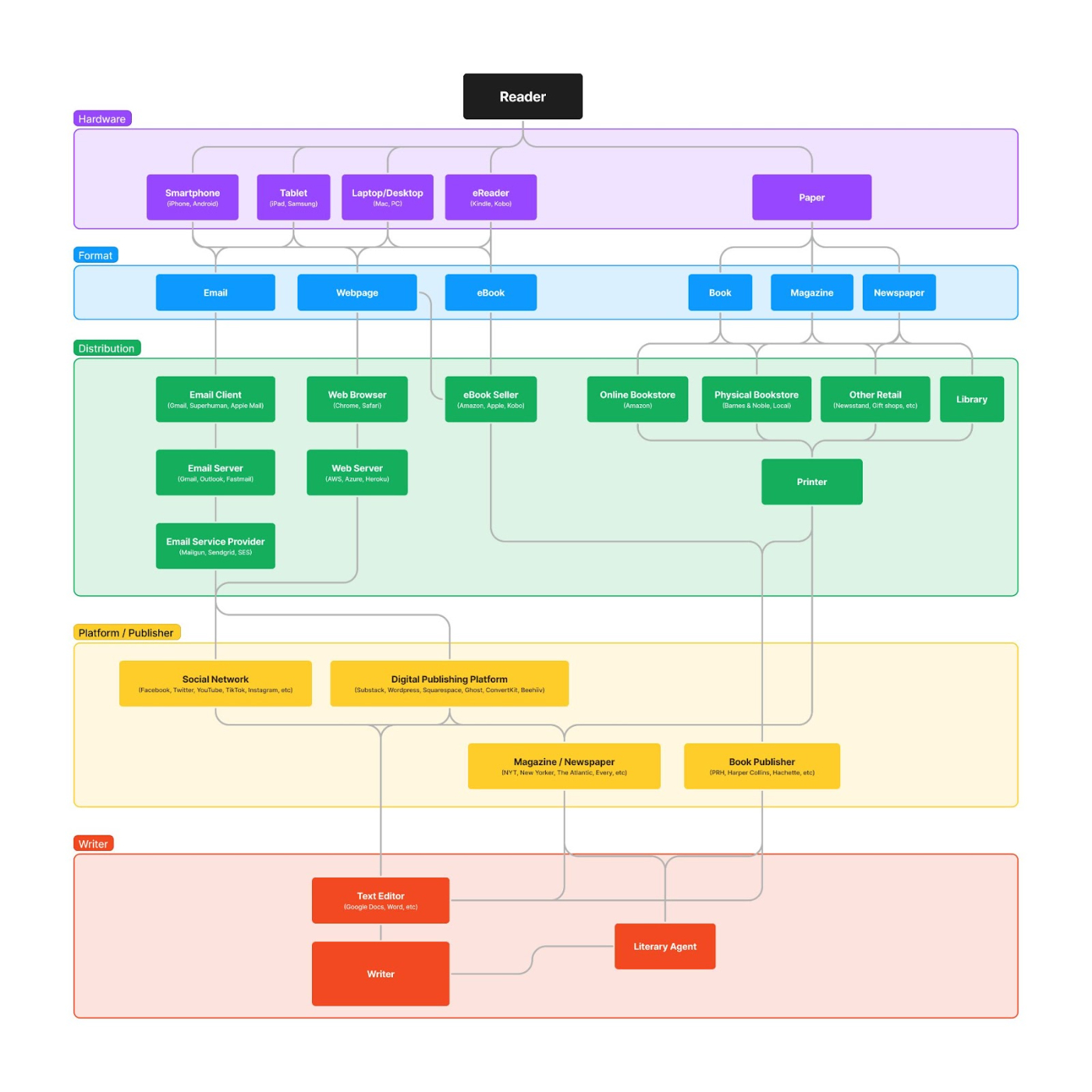

3. Mapping the writing value chain

What needs to happen in order for words to flow from writers to readers? What are the control points along the way? Who captures value?

These questions are more easily answered by a map than in prose.

(You can see a larger version of this image by clicking on it, or you can view the original Figma file here.)

This map simplifies an incredibly complex and non-linear process into a fairly simple representation, but the process of creating it is super useful. If I had more time I would love to layer in a few more pieces of information:

- Share of attention. For example, how much of readers’ time is spent on print vs digital, broadly? And within those broad categories, how much time is spent within each sub-category (e.g. book vs magazine, phone vs tablet, etc).

- Share of revenue. How much money is spent within each chain, and who takes a cut along the way? Who generates the most revenue? The most profit?

- Specific businesses. Right now I name categories of products (e.g. eReader) and list a few examples under some of the less self-explanatory ones, but it would be cool to have a list of businesses by market share. Basically, take the two metrics above (attention and revenue) and segment them not only by each box above, but each business competing within an individual box.

- Loops. This is a map of a dynamic system, so it’s important to model it as containing positive and negative feedback loops. For instance when a reader hears from a friend about a book and reads it, there’s some chance they’ll tell other friends, or follow the author on twitter, etc. But there are also other loops like if they choose to listen to an audiobook and enjoy it, they might be more likely to listen to audiobooks in the future.

One last thing to note before the next section: make a map of any industry and you’ll probably see a section similar to the left hand side of the green “distribution” layer. Everything that can get sent over the internet, will get sent over the internet. And the way it gets sent has to conform to the various standards and gatekeepers that control the way the web works. This is why large technology companies like Apple and Google have so much power.

4. Locating the position of power

Looking at the map above, what steps have the biggest impact on the basis of competition?

The number one thing is that box at the very bottom: writer. Some people are able to put down words that lots of people want to read, most of us do not. It’s useful to ask what activities or attributes make some writers more successful than others and to perhaps break apart the single box “writer” into a bunch of smaller boxes representing various activities.

For example:

- Having life experiences that people want to know about

- Spending a lot of time reading great stuff

- Becoming an expert on something

- Getting feedback from high-quality editors

- Establishing relationships with insider sources

- Spending a lot of time writing

- Publishing consistently (which is a distinct skill!)

- Developing a healthy emotional relationship to the highs and lows of writing

There’s a whole world of stuff in here, some more important than others. But my theory is that if you look at successful writers, they figure out a way to get a lot of these forces working in their favor.

Another layer of the value chain where a lot of power tends to accrue is the “Platform / Publisher” layer. These are important because they are the places readers tend to go directly for content, or they control access to those places. For instance if you want to publish news about something happening in the White House, you can instantly reach an international audience if the New York Times agrees to publish you. Of course you can also just go direct onto a social platform (and sometimes the information you have is so powerful or entertaining that it breaks out) but generally publishers help accelerate you. And the publishers themselves are often pretty reliant on open platforms to disseminate their writing, anyway, because hundreds of millions of people go there looking for writing every day.

There are some layers, however, that don’t command much power. For example text editors. People have attempted to make fancy software that helps writers, but so far it has not been easy to form a competitive advantage around. Google Docs and Microsoft Word are the state of the art, and they are simple, cheap, and made for many different use cases. There’s a long tail of apps for writers but none of them have significant power in the ecosystem.

Interestingly, this is not inevitable. For example in the music industry Pro Tools, Ableton, and Logic have a bit more power. It’s uncommon to use anything else and it costs a decent chunk of money because the software has a more direct impact on how the music sounds, and achieving a unique and high-quality sound really matters in music. These digital audio workstations also have extensive ecosystems of plugins, so they have a network effect. The closest thing I could think of that’s like a plugin for writing is Grammarly, but I’m pretty sure very few professional writers actually use that. Maybe AI-assisted writing tools will change this?

5. Tracing the source of that power

This is my favorite part. Let’s start with writers, then cover publishers and platforms.

What forces keep writers’ brands so powerful? I actually wrote about this in-depth in my most popular article ever, “Why Content is King.” I go through each of Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers and talk about the ways in which content and stories can create economic power structures that we typically associate with technology businesses: network effects, switching costs, economies of scale, etc. That article isn’t specific to writers, but everything a writer does fits into the framework I laid out in that article.

Here is a preview:

- Network effects—all else equal, it’s more valuable to read Malcom Gladwell than a random nonfiction author, because Malcom Gladwell’s ideas are in a lot of other people’s heads, and you want to understand and relate to those people and predict how they will behave.

- Economies of scale—Malcom Gladwell has a bigger budget than you to do research for his next book. (This one is far less powerful in writing than in other forms of storytelling like superhero movies.)

- Switching costs—Once you’re a fan of Malcom Gladwell, it’s easier to read more stuff by him. You become familiar with his work and bought into his worldview.

(There’s more in the post but this gives you a taste.)

The dynamic I am most interested in, though, is how people get started. The forces I just described keep people on top for a long time after their output slows or declines in quality. But what makes a writer take off?

A lot of people will just shrug and mumble something about talent, but I think it’s better to attempt to crack open the black box of success. To me, the biggest early force that affects writers careers is a specific form of “economies of scale”: becoming a full-time writer. It’s extremely hard to get to the point where you can write for a living. But once writing pays your bills, you can spend a lot more time doing it. This creates a feedback loop where you get better and grow your audience faster. I think the “make it to the point where you’re full time” thing accounts for a huge proportion of success. For example, Evan Armstrong over at Napkin Math has been on an absolute heater ever since he went full time this spring, and he’s only going to keep getting better from here! Once you make it past that point, the pool of peers to compete with gets dramatically smaller.

Anyway, how writers acquire power could be a whole book unto itself, so let’s turn our attention to platforms and publishers now haha :)

It’s no surprise that platforms are incredibly powerful when they have network effects. Not just for the writing industry, but for all industries. This is why Facebook has been one of the most powerful companies of the 21st century so far, and why even Twitter which is tiny in comparison still matters so much to so many different types of writers. But this is obvious, and I would like to focus more on the interaction between new publishing platforms (like Substack and Medium) and how they compete for supply of great writing with traditional publishers (like the New York Times and Penguin Random House).

Substack attracted more hype and high-caliber writers to go all-in than Medium did (although Medium has been great at getting public figures to publish free, casual content), but the number of professional writers who go direct to their audience on any of these platforms is tiny compared to the writers who choose to go through traditional publishers. And the momentum seems to have slowed down, if only temporarily. Why?

Publishers provide a few key services to writers that platforms like Substack haven’t been able to compete with (yet):

- Financing (economies of scale)

- Distribution to an audience (network effect)

- Brand prestige (brand / network effect)

- Editorial support (economies of scale)

- Legal support (economies of scale)

(Those are roughly in order of importance.)

Substack is growing faster than Medium because it’s done a better job serving the kind of writer that will generate significant readership and revenue, but the real prize is when they have an attractive enough proposition that the average professional writer decides they’d rather go direct on Substack than work with their publisher.

This is why Substack is so laser focused on building out a network effect where writers can get more readers by being on Substack. They are doing it with one hand tied behind their back, thanks to their anti-algorithm ideology, but so far it seems to be working well at least for top publications. Their big feature is one that lets publications recommend other publications, and it’s driving significant growth for writers. This is the kind of thing that could really eat away at the benefits of working at a traditional publisher.

This is also why Substack Pro—their means of offering financing—was such a big deal. Back in 2020 when Substack had a huge growth spurt with lots of high-profile writers coming onto the platform, a big contributing factor was that they got more aggressive offering big-name writers big upfront money to join.

Now that Medium has a new CEO, it will be interesting to see if they try to serve the same profile of writer, or if they have a different audience they are targeting. And will other platforms like ConvertKit or Beehiiv make any inroads? My take so far is “no” unless they work harder to chip away at the same types of value publishers offer.

It will be interesting to watch!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

are you writing said book about writers obtaining power?