Why Polarity Pays

The complicated social and financial incentives at the heart of online publishing

A blog post can move mountains. Prose, wielded correctly, is an explosive, world-changing energy. But, because writers are often constrained by the revenue and cost structures of a media business, they can only capture miniscule portions of that value. Writers are valued by society for their independence and good judgment, not for their ability to make money—and the ways in which writers make money are always somewhat suspect.

Therein lies the polarity in tech coverage: unabashed, reckless boosterism from tech bros and cruelly negative coverage from the traditional press.

We can explain away both the techno-utopian media and depressed, grumpy Slate articles by examining the incentives driving their respective businesses. Every single market force pushes writers toward starry-eyed optimism for sway, or toward jaded negativity for scale. These are the economics of tech writing. I’d like to think this publication has succeeded in the vanishing middle between these two gravitational fields, but that’s not an easy thing to do (and, as a result, has created a smaller business than if we were to embrace either of these extremes).

Tech companies continue to get richer, more powerful, and more ambitious—figuring out how to read the tea leaves about what they’re up to will give you an advantage in your life and career. Understand incentives and you’ll understand the world.

Incentivized polarity

The issue is this: Technology analysis is a shitty enterprise. A company that has to fight for every dollar of additional revenue struggles to hold the costly moral high ground.

When a media company makes something of value—say, a poignant or revelatory article, video, or podcast—it’ll be rewarded with social capital (trust, awards, inclusion) and with distribution (subscribers, readers, social media attention). Still, the economics of publishing on the web are so dreary, ever incentivizing gluts of free ad-subsidized extremes over well-researched and nuanced work, that it's hard to make much money even with a large audience.

However, in business media, there’s another option: Rather than scale, you can find a way to profit off equity. Cultivate favor with a small crowd of powerful people, and then find ways to get a piece of what they are building or investing in.

The two media archetypes are roughly this:

- Scale play: Write articles that are generally negative (if it bleeds, it leads) and only cover topics that have mass-market appeal. The general public is mostly interested in scandal as compared to progress. After all, there is a reason that true crime is the most popular podcast genre, not true-case studies on how I scaled my plumbing business. Everyone knows Adam Nuemann’s WeWork, but very few know the scientists who built the internet.

- Sway play: Write articles that appeal to your chosen audience of professionals. This means playing nice, cultivating sources, and glad-handing. In particular, if you’re not in the news business and don’t have the explicit mandate to get investigative scoops, you are gradually incentivized to be overly optimistic.

To be clear, I am not saying either of these options are morally corrupt or incorrect—I know great people employing both strategies. My point is that there are very real, very painful market forces impressed upon every person who writes online. The best media businesses cultivate a combination of revenue streams and social capital for their future benefit, but business media has the extremely tempting option of equity stakes.

The incentives are intensified when you switch from writing about publicly traded tech firms to private ones. For public companies, there are financial rewards for price discovery. Investors want to know the good and bad about a company’s business to determine whether a stock price is trading above or below true value. In private markets, there is no real way to profit off of a tech company’s demise, so there is no strong incentive to publish nuanced, net-negative analysis beyond a scale play.

However, positivity pays handsomely in private markets. You can get equity if the right founder or venture capitalist trusts you. And because business failure is only interesting in cases of outright scandal (like Theranos) rather than the more regular stuff like “the market was too small,” it is a distinctly sub-scale play, one that will be deemed uncouth by sway-play audiences because of the icky feeling of grave dancing.

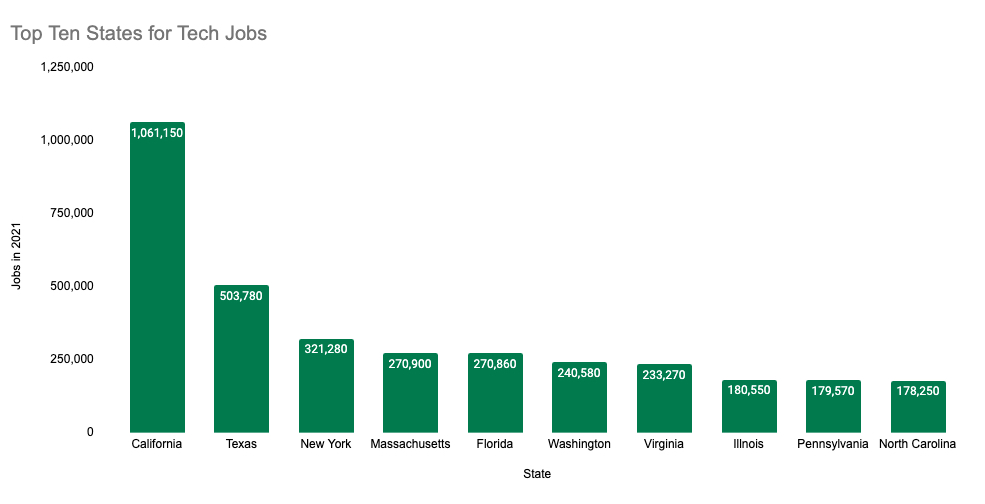

A scale play in tech media requires capturing a significant portion of the overall tech workforce (probably 3.5-6.5 million users depending on how you cut the data).

Every illustration/Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A sway play means you don’t have to worry about mass distribution as much. When you add together the roughly 54,000 venture-backed startups, 390 publicly traded tech companies, and 10,000 venture capitalists in the U.S. you get an audience of decision-makers around 100,000. Most crucially, you only need one of them to agree to some sort of equity product. It is power-law content: Invest once, publish forever. If your audience can stomach the conflicts of interest, it is a wonderful way to make money. Write positive coverage of the tech industry, become part of the in-group, and you’ll see rewards in terms of access to scoops, equity stakes, and additional responsibilities.

You either need to cheaply get virality to capture those 4 million tech workers or cultivate power with those 100,000 people. These dynamics are so powerful that unless you are a very famous analyst or a journalist organization focused on scoops, the end result is that many great tech writers end up as investors. Ray Dalio, founder of $124 billion hedge fund Bridgewater, started off his career writing a newsletter. Michael Moritz, one of Sequoia Capital’s former leaders and one of the greatest VCs of the last 40 years, was a Time magazine reporter prior to joining the investment firm. Shoot, it feels like half of former TechCrunch staff left journalism to work at VC funds.

'You’re right but I can’t say so'

I recently published a critical review of a16z general partner Chris Dixon’s book about crypto. I was as fair as I possibly could be—the piece was heavily researched and carefully considered. I read the book twice, had my facts checked by multiple crypto-minded friends, and felt confident in my conclusions. My argument was that while crypto has specific niche use cases, its promise has been greatly overstated, and properties inherent to the technology will mean it won’t live up to what Dixon believes. (Dixon, of course, is no neutral narrator either: He manages over $7 billion with investments in companies like Coinbase. He’s staked his career and reputation on the success of crypto.)

In private, the article struck a chord. One prominent crypto VC—who has a following 15 times larger than mine on X—messaged me to say, “I think you are right but I can’t say so because then I wouldn’t have a job.” In a sense, I achieved sway, but negative takes will never give me access to equity. (No one is saying, “Thanks for that blistering review, Evan. Have a chunk of my company!” And if they did say that, I’d have to wonder if they were simply trying to buy me off.)

However, because the article was long and nuanced, it didn’t go truly viral. I know this because I published a short and grumpy take on crypto two years ago, “Crypto’s Failed Promise,” that went nuclear. It was dumber, but it was topical. It has some analysis I’m not sure stands the test of time. And I grew my audience because of it, but maybe I traded some amount of reputation with people who would give me equity opportunities.

This is a problem that I—and the larger Every team—have grappled with for years now.

My personal goal has always been rigor first. I want to publish nuanced takes that don’t feature outlandish claims. Unfortunately, that isn’t a product that translates neatly into either sway nor scale. Most people care about quality analysis only if it directly benefits them, entertains them, or makes them money. I first started wrestling with this in 2022, in the performance review of myself I published:

“Perhaps the most surprising outcome of my analysis was that there was no relationship between how viral a post was and its accuracy. Some of my most intelligent, spooky-good analyses barely got read, while some of my dumbest takes got shared all over the world.

As far as I can tell, my pieces’ virality is driven by my ability to sound smart, not being smart. The post that sounds convincing and is written in an entertaining way will get more traction than a dull but accurate and intelligent take.”

Now that attention platforms like X and Google are sending publishers ever-less traffic, these observations are even more true. You have to be more extreme (in either direction) to drive virality.

To make this all more complicated, I’ve only discussed individual-level incentives. It gets way harder when you try to do it as a team.

Anyone who is smart enough to be good at tech writing could certainly make more money doing other things. Rejecting offers for more money and stability is easy when you are young, but the older and more experienced a team gets, the more tempting easier money becomes.

Our co-founder Nathan Baschez is a great example. He is an incredible writer who decided he would rather be building a venture-backed tech company. The same innate capabilities that made him a pro at writing high-quality analysis might make him far richer as a startup founder. (We are fully biased here and hope he crushes it.)

To get around the tech money temptation, we’ve tried structuring our roles differently than a traditional media company. We incubate software products and companies. (More on our next project soon.) Our team is also very lean, with just four full-time staffers—two writers, an editor, and a designer—so that as we scale, we can automate work with software and give ourselves raises.

On top of internal equity-building, we’ve also allowed team members to pursue adjacent projects that don’t neatly map onto writing. Dan is a scout for Sequoia Capital, and I’m involved with a venture firm called Indie. We haven’t raised a fund ourselves because 1.) we love writing and 2.) the incentives are complicated. But even this half-way path isn’t without ethical complications. For example: While I was writing a profile of a startup, Dan invested in it—but it was a coincidence since we never discussed it. Our solution is that I will disclose the conflict when I publish the story, but this sort of thing happens to us all the time. We’ve justified a cozier relationship with the companies and industries we cover—albeit with proper disclosures and transparency—because it allows for a more rigorous editorial product. Additionally, since everyone we publish comes from a background as operators or investors, conflicts of interest are part of our original value proposition!

Our team loves writing enough, and our traction is strong enough, that I think we can grow to a sufficient size that the opportunity cost won’t be overly painful. But no matter how big we get, we’ll never outgrow the market forces that dictate how all media companies find audiences on the web and interact with the entities they cover. We’ll always be stuck somewhere in the middle.

We believe in technology—we love it, in fact—but that never means we’ll turn a blind eye. We will cheer for startups to take down the big guys, but we won’t pull our punches if the truth needs to be spoken.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Appreciate the honesty and ethics

Goes to show the current state of the eyeball economy, even hard work hits a growth ceiling.

Great analysis

Thank you for actually reflecting on this stuff.

Thank you for the nuanced reflections. I used to work in financial publishing and witnessed several crossovers from journalism to investment banking, financial PR, and startups.