Sponsored By: Flatfile

There comes a time in every project that you’re tasked with implementing a CSV importer. With Flatfile, you no longer have to agonize over starting from scratch...again.

Slash time-to-value, onboard customers faster, and cut product churn with a 1-click data import experience from Flatfile:

- Cut hours off data cleaning and focus on growing your company.

- Import customer data in less than 60 seconds.

- Migrate data using stringent compliance standards

Since launching in 2018, Flatfile has onboarded data for over 1.5 million customers spanning 400+ of the best companies around the world. In just a few clicks, Flatfile intelligently imports, transforms, and validates your customers’ data, solving the most critical part of onboarding, in seconds.

I’m not a perfectionist, I’m too enlightened for that. But I am concerned with making things turn out great. Both performance-wise, and morally. I know you can’t achieve perfection, but you can asymptotically approach it. And that’s really all I’m after.

When the graph of my performance approaches the asymptote it’s like no other kind of high. When I’m pounding out words and they’re coming out right, or I’m making decisions and moving the pieces around on the chess board at Every and watching the numbers go up, or someone tells me I’m a good person or I did a good job. Ahhh, the best.

When that’s happening it’s like there’s an invisible string pulling me up by my heels, straightening my back, and puffing out my chest, so I’m gliding on tiptoes down the street. I’m proud, I’m special, I’m happy, I’m motivated. In short: I’m the shit.

My co-founder Nathan, though. He’s a perfectionist. You should see that man design a logo, or write a sentence. Agonizing over every little detail. Crushed when it doesn’t go right. I’ve been trying to help him with it. (May I remind you that I’m a Very Good Person—not yet Jesus, but approaching the asymptote!)

The thing is I haven’t been able to fix Nathan yet. Perfectionism is a tough nut to crack.

That’s why I got so excited when Dr. Clarissa Ong and Dr. Michael Twohig, the authors of The Anxious Perfectionist, reached out to me about their book. It’s about science-based tools for overcoming perfectionism, and so I suddenly had a perfect plan: Nathan could read the book, and then I could have him chat with the perfectionism people, and maybe he’d figure out how to chill out. I set up a call with all of us, but Nathan didn’t show up. (Classic perfectionistic avoidance.)

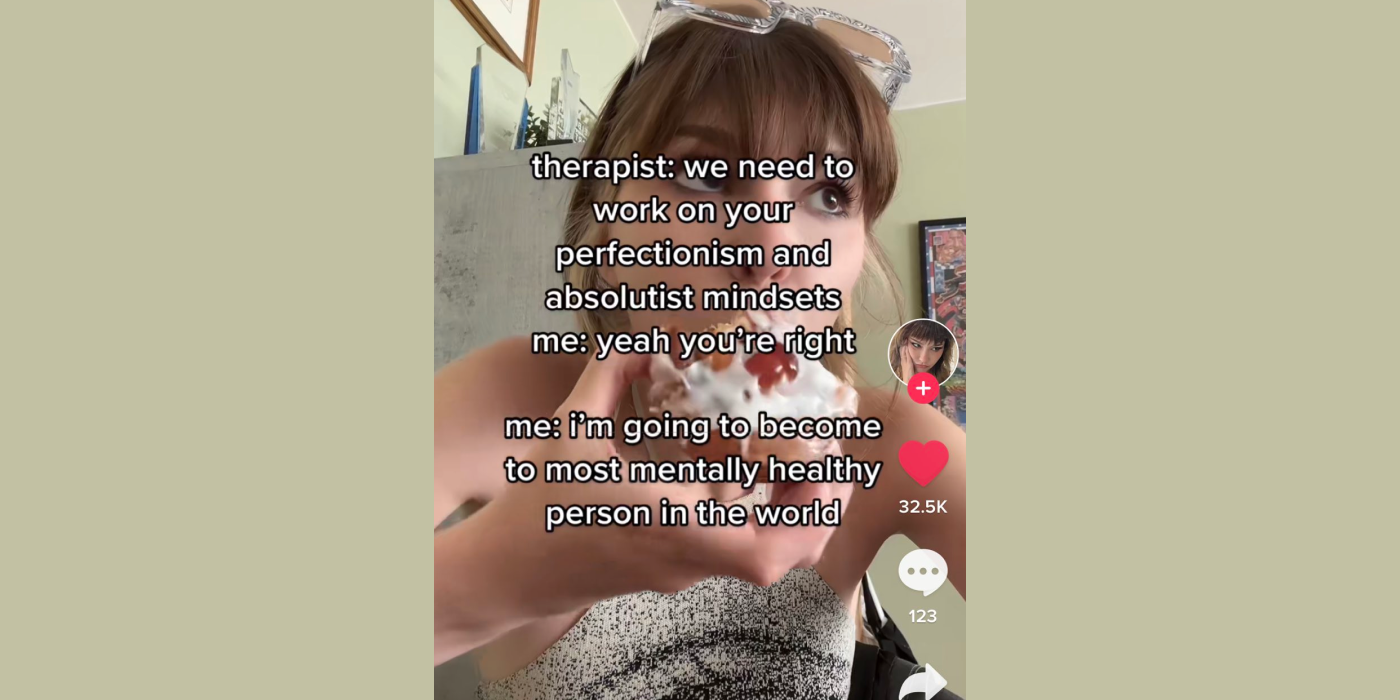

But I was on the call, so I started talking to them about perfectionism—you know, for the science of it all. And a lot of what they said sounded um familiar. I took one of the classic tests, the Frost Brief Perfectionism Scale, and scored a 32 out of a possible 40. And something began to dawn on me:

When it’s something I’m doing, perfectionism is just what’s called “doing a great job.” When someone else is doing it, it’s called perfectionism.

What I learned from Michael and Clarissa is that most people don’t really understand what perfectionism is. We think it’s about doing great work, and we wear it as a badge of honor to show how much we care. We don’t really want to give up on perfectionism, because we think that means giving up on the exact traits—like high motivation, and attention to detail—that make us awesome and make our work awesome.

I know how I got this way. I realized early on that if I jacked up the perceived costs of my mistakes I was much more likely to have the energy and drive to do more and better work. And I don’t think I’m alone:

But what I learned from Clarissa and Michael is that perfectionism doesn’t actually lead to better performance or work outcomes. Instead living with perfectionism creates avoidance behaviors like burnout and procrastination, induces extreme amounts of micromanagement, and often causes sufferers to miss the forest for the trees. It can sometimes even lead you to try to fix all of the flaws in your co-founder rather than looking deeply at yourself. (I am, of course, not speaking from personal experience here at all.)

What’s most interesting, though, is that working on perfectionism doesn’t mean giving up on doing great work. It’s not the wanting to do great work that’s the problem in perfectionism—it’s that people who suffer from it are extremely rigid about what good work looks like, and how it should be accomplished. The rigidity is the problem, not the desire to do great work.

If you can work on the rigidity, you can actually do more and better work—without suffering from the negative consequences of perfectionism.

This was a pretty big realization for me and so I wanted to go down the rabbit hole with it.

I wanted to understand: how do we do great work without falling into the trap of perfectionism? I asked Clarissa and Michael to co-write this article with me to help us answer that question. They’ll define what perfectionism is, and outline strategies that we can all use to work with our perfectionistic tendencies.

Let’s dive in!

What is perfectionism?

Perfectionism is the intersection between excessively—usually unrealistically—high standards and rigid adherence to those standards.

Usually, in perfectionism the standards are not the problem. The problem is the rigidity around those standards. The rigidity means it’s all or nothing, so we hyperfocus on achieving our impossible goals, only to burn out, neglect other responsibilities, avoid our goals altogether, or constantly feel miserable even when we’re objectively doing well.

Using this formula, rules + rigidity = perfectionism, we can usually distill perfectionism down to a set of rules we have in our heads, such as “I can’t compromise if I want to be successful,” “I need to do things the right way,” or, “If I don’t succeed, there’s no point.”

Often these rules are helpful. They can be motivating, and they point you in the direction of what you most value: doing great work. But the problem is following these rules rigidly all the time can have the opposite effect of their intended purpose: they end up moving you further away from the outcomes you’re striving so hard to attain.

The antidote to perfectionism is not getting rid of your rules—it’s understanding what they’re designed to help you achieve, noticing situations where they’re helpful versus hurting, and being flexible enough to follow them when they’re helpful and disregard them when they’re not.

The science supports it: we’ve conducted several studies that have found that the skills covered in this article enhance well-being and reduce the psychological symptoms present in perfectionism.

From rules to real life

Take a second to think about some of the rules you’re following around your work. What are a few that come to mind?

Here’s one that might resonate: “If I don’t completely pour myself into my work, it won’t be any good.” Or here’s another one: “If small details are off, it ruins the whole thing.” Or here’s another one: “No one else cares about the work as much as I do, so I have to work twice as hard to make sure things turn out okay.”

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!