I don’t understand Marshall McLuhan.

He’s the guy who wrote, “the medium is the message,” a phrase you may have invoked at meetings and parties, trying to sound worldly and intellectual. I have, too.

But the honest truth is, I don’t get him. And despite how many times I have heard it and even repeated it myself, I don’t know why, exactly, the medium is the “message” versus any other thing it could be.

I really feel like I should. The phrase, and the book it appears in Understanding Media, predicted much of the impact of the internet before the internet was even a thing. It’s a phrase about the future, coming from the past. And I feel like if I understood it better I might get something important about how to understand technology’s effect on the world—an understanding that I could apply to things I see all over, from Web3 to AI to what we’re building at Every.

McLuhan is referenced everywhere in media and in tech. Wired Magazine founder Kevin Kelly named McLuhan Wired’s “patron saint.” Elon Musk cribs him in memes. Heck, even my co-founder Nathan cites him a lot.

The problem is that the sentence, “the medium is the message” occurs inside of a book that doesn’t make any sense. Reading Understanding Media is like trying to climb a rock wall coated in petroleum jelly. I’ve attempted it a few times, but I keep slipping off and falling on my butt. The first page doesn’t make sense, so I skim to the second page to see if my hands can find a convenient grip. But I just can’t find anything that gets me off the ground. Instead I get slippery zingers like this one:

“As extension of man the chair is a specialist ablation of the posterior, a sort of ablative absolute of backside, whereas the couch extends the integral meaning.”

Anyway, at this point, I know you probably feel the same way. You’re probably feeling like Mr. McLuhan’s use of the English language is some sort of ablative absolute of the backside. I concur.

But it would be really awesome if I—we—did understand what “the medium is the message” actually means.

So I decided to try to break it down. To do that, I read the first two chapters of Understanding Media where the phrase is introduced. I’m going to tell you what they say in as few sentences as possible.

Ready to go snorkeling in the depths of Lake McLuhan? Here goes.

Technology is a way of extending ourselves: our bodies and our senses

Understanding Media says it’s a book about media, but it’s really about technology. In the book, “media”, rather than referring specifically to the press or a type of content, is just the plural of “medium”—which is used interchangeably with “technology”. McLuhan sees media like TV, newspapers, and books as a kind of technology, and so his analysis places them on the same continuum as things like lightbulbs and airplanes.

So the book is about understanding technology. To do that, McLuhan has to answer another question: what is technology? He thinks of technology as “extensions of man”—technology is a way of extending our senses and our physical bodies beyond their natural physical limits.

This is a very interesting idea. It means we can look at something like a cup or an airplane or a TV through a new lens: a way of extending our natural capabilities. A cup extends our hands to hold a substance that they weren’t built to hold. An airplane extends our ability to move, and allows us to move many times faster than our bodies were originally made for. A TV, in McLuhan’s parlance, extends our nervous system, and allows us to experience things we would have never come into contact with otherwise.

We’ve been inventing these kinds of extensions for at least a few thousand years, and using our extensions to create more advanced extensions. McLuhan sees this as having created an “explosion” of our abilities outward. We can do more things in the world, we can cover more ground, we are extending our bodies in massive and important ways.

But he thinks there was an important change when we moved from mechanical technologies like cups or planes to electric technologies like the telegraph, the telephone, TV, and the radio. (He would say the same thing about the internet, but this book was written before the internet was really a thing.)

“Electric” technology creates a hive mind: it hooks our consciousnesses up instantaneously to every other consciousness in the world

Where previous mechanical technology created an explosion of our abilities outward, McLuhan believes that electric technology creates an implosion inward. He calls it an implosion because it collapses the usual boundaries of time and space between our consciousness and the consciousness of others. It hooks our consciousness directly to the consciousness of everyone else in the world simultaneously. To McLuhan, it means that we are no longer separate, and we are continually exposed not only to other people, but to to our impacts on them:

“In the electric age, when our central nervous system is technologically extended to involve us in the whole of mankind and to incorporate the whole of mankind in us, we necessarily participate, in depth, in the consequences of our every action.”

This is kind of true! Telegraphs and telephones and cellphones and the internet mean we are instantly aware of things that have happened that relate to us, even if they happened hundreds or thousands of miles away.

(It’s worth wondering here: doesn’t the written word in books have much the same effect as electric technology? The answer to that question is a little bit more difficult to find. He does think there’s some similarity: “The printed word extended the minds and voices of men to reconstitute the human dialogue on a world scale that has bridged the ages.” But he also thinks printed books create a sort of detached culture of knowledge, what he calls being able to “act without reacting”, a kind of cold, uninvolved view of the world that is being disrupted by the heightened connection offered by electric technology. I can’t really get on board with what I understand of this, to be honest. But I don’t think it’s central to the point of this article.)

This broader point about the “implosion” created by electric technologies is actually very insightful given when it was put down on paper. Remember, McLuhan wrote this in 1964! Way before things like email and Slack and text messages became a thing. His ideas presage all of the conversations we’re having about our always-on, technology enabled work culture, and the impact of the internet on our mental and physical health.

That said, it’s probably not 100% right. I have quibbles with the idea that we necessarily “participate, in depth, in the consequences of our every action” through electric technologies. Connecting the world does not, by itself, get rid of hatred, misunderstanding, or divisions—and in fact often makes them worse.

I don’t think that’s what McLuhan is arguing for, however. He admits later in the book that no “technology could do anything but add itself on to what we already are.” So in his view, this level of heightened connection amplifies some of the good and some of the bad in human nature in different ways.

It’s at this point in the text where he gets to the bit we showed up to this whole party for: the medium is the message. Okay, here’s the sentence:

“In a culture like ours, long accustomed to splitting and dividing all things as a means of control, it is sometimes a bit of a shock to be reminded that, in operational and practical fact, the medium is the message.”

There’s a lot going on here, so let’s try to break it down.

The “message” of any medium is how it changes our relationships to each other and the world

In plain English, "the medium is the message" means that to understand technology we need to understand how it extends, accelerates, or impedes existing human behaviors and relationships.

What he means by the "message" is something more like the "impact" or the "meaning" of a new technology, rather than the actual messages it might carry. The medium is the message, because in his opinion, the biggest impact of a new technology comes from its ability to change the scale or pace of human life and when we analyze it we should do so with that in mind.

He says, “The railway did not introduce movement or transportation or wheel or road into human society, but it accelerated and enlarged the scale of previous human functions, creating totally new kinds of cities and new kinds of work and leisure. This happened whether the railway functioned in a tropical or northern environment, and is quite independent of the freight or content of the railway medium.”

This is very mind-bendy. What he’s saying is that the thing that really matters about technology is the thing that is usually invisible to us. And if we can learn to see what’s invisible—the medium rather than its contents—we can better understand and predict the impacts of that new technology.

For example, in the case of NFTs our behavior is changed significantly by the fact that NFTs accelerate and expand the scale of existing human behaviors like the coveting of scarce resources, or participation in group rituals and signaling. But our tendency is to focus more on “right-click save” gotchas, or the inherent quality (or lack thereof) of NFT art.

The next obvious question is, why is the medium usually invisible to us? Why do we focus on whether NFT art is good looking, rather than on how it enables status signaling through scarce digital resources. And the answer lies in the first part of the original quote: his reference to “splitting and dividing things as a means of control.” What does that actually mean?

What he’s saying is that what we normally do when we want to understand new technologies is to split them up into their component parts. It’s the analytical, scientific mindset that’s helped us produce everything from our knowledge of atoms to the internal combustion engine. We look past the medium and instead look to understand its contents, and in the case of a medium like Twitter or a TV or an iPhone its contents are its literal messages. To understand a TV broadcast we look at what the anchor says, or what the plot of the show is. On the internet we think about the latest TikTok dance meme, or the Bored Ape Yacht Club.

But, in the case of technology, McLuhan believes this reductionist tendency to split apart and look inside—to look only at the contents of a medium—is actually missing the point.

This is useful, because the contents of any new medium look silly at the beginning. It’s exactly why Twitter was written off early on. (Why would anyone want to know that I just ate a burrito?) But the contents of a medium often make invisible the potential impact of the medium itself on our lives and behavior.

And if we can learn to look at the medium too, we might be a lot better off.

But will we?

A few tentative conclusions

There’s definitely something interesting about this McLuhan guy. I like the idea of technology as an extension of ourselves, and that there’s something invisible to us about it. I like the idea that when we try to understand technology by looking inside of it, we’re actually missing the large ways in which it might actually impact our behavior, our relationships, and our lives.

It’s very difficult to put into practice though.

I can make references in this article to the ways that NFTs might “accelerate and expand the scale of existing human behaviors like the coveting of scarce resources”—but what is that really saying? Do I really believe it? I don't know. I think it’s mostly an easy way to be less skeptical of new technologies, to turn our attention away from their silly initial use cases, and instead look to their possible future. It’s a phrase that creates bias for optimism. Which is incredibly useful!

But if we want “the medium is the message” to be anything more than that, I think we might be a little bit disappointed. It’s a lot to expect a 50 year old maxim to be able to specifically predict the next 10-20 years.

It’s fascinating to get pulled in by McLuhan, to give in to the urge to unpack the esoteric mystery of his book, and to attempt to find the "genius" predictions hidden underneath. There is something to it, for sure.

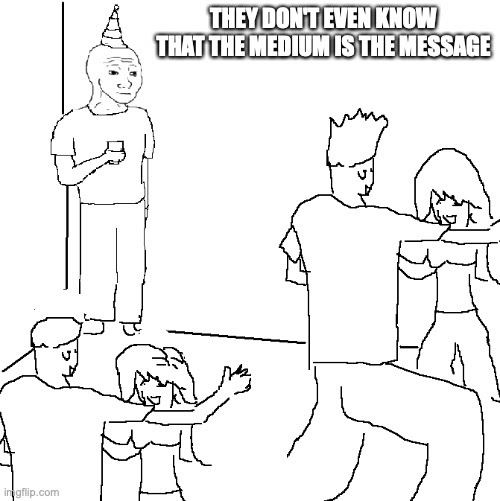

But the phrase "the medium is the message" is also, for me, still mostly a way to message in-group status as much as it is a way to actually understand what’s going on. It's a meme in its own right.

After a few days of reading, I found a small tool I can use to understand the world better. But in the end, it's mostly a good way to understand myself—my desire to look smart, to be part of a group, to be able to know and predict an unpredictable world.

What do you think? Did I miss something about McLuhan or this phrase? What does it mean to you? Leave a comment and let's discuss!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!