Sponsored By: MasterWorks

Why Are Bezos and These Billionaires Investing in This $3 Trillion Trend?

The global wealth of billionaires has soared 70% since the global health crisis began. Although billionaires have unlimited access to stocks, luxury homes and private equity, analysts believe investments in art could hand them their biggest payday.

According to the WSJ, “Art is among the hottest markets on earth”. Now, the ultra-wealthy are pouring money into this asset class.

Collectively, Steve Cohen, Bill Gates, and Jeff Bezos hold billions of dollars in art.

Here’s why:

- Contemporary Art prices outpaced the S&P 500 by 174% (1995-2020)

- Traditional inflation hedges by 4x when inflation is over 3%

- Global value of art expected to reach nearly $3T in under 5 years

With Masterworks.io, the $1B tech platform, you can invest in multimillion-dollar paintings by Warhol, Picasso, and Banksy, just like buying stocks online.

With over 270,000 members, Masterworks is off to the races.

Why not join them? Superorganizers Subscribers get priority access*.

*See important disclosure

The Good Place is one of my favorite shows. It’s about a woman who wakes up in heaven, but realizes she was sent there by mistake and must cover it up or risk being sent to hell. It’s hilarious, but it’s also dream TV for a philosophy nerd like me. The primary way that the main character tries to stay in heaven is to learn to be good, and she does that by being taught most of the major strains of moral philosophy in the West—from deontologicalism to utilitarianism to contractualism. (Hint about being “good” in this show: it’s complicated.)The philosophy content strikes an incredible balance: it’s both easy to understand, hilarious, and it’s right. I've always wondered how they do it.

That’s why I was so excited to sit down with Dr. Pamela Hieronymi. She’s a professor of moral philosophy at UCLA, and is the “consulting philosopher” on The Good Place. Yep, that’s right, when the characters are bantering about the finer points of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason she’s the one who’s in charge of making sure the banter is, well, accurate.

Dr. Hieronymi’s philosophy work centers on moral responsibility and free will. More specifically, she thinks mostly about the active/passive distinction: the difference between events that happen to us, and things that we do in the world.

There’s something deeply romantic to me about the idea of being a professional philosopher (which is maybe why I majored in it.) But there’s also something important about the tools and systems that philosophers like Hieronymi use to create and explain the complicated chains of logic and abstract reasoning necessary to make contributions in their field.

These kinds of thought processes are relevant to all of us, even if we're not explicitly doing philosophy. After all, a life of knowledge work is, to some degree, a life of the mind. And so there is a lot to learn from how the minds of philosophers navigate their work lives.

In this interview we talk about how Dr. Hieronymi keeps up her publishing pace, how she acquaints herself with new fields of study when she needs to get up to speed quickly, and what her writing process is. We dive into how a new philosophy paper is born, and how she shepherds it to completion.

Let’s dive in!

Dr. Hieronymi introduces herself.

My name is Dr. Pamela Hieronymi. I am a professor of philosophy at UCLA, where I started out immediately after getting my PhD from Harvard in 2000.

My subfield within philosophy is ethics, but within that my specialization is moral responsibility and free will. I like to think about the agency or control that we enjoy with respect to our own states of mind, and my driving interest is the active/passive distinction—the distinction between what we do, and what merely happens to us.

In my opinion, doing philosophy well is about giving a full hearing to all sides of a debate: doing your best to understand each conflicting point of view, what it has going for it, and where it goes wrong. The aim is to pull the truth out of each of those, add your own insights or creativity, and end up with somewhere you can stand.

Part of my job is to give back to philosophy by creating new writing—making my own contributions to the field. And to do that well, I have to stay current in my discipline and engage with new ideas. That means taking in huge amounts of information.

How I approach reading and absorbing information.

Some people in my field just devour the literature, and they are somehow able to hang onto what they’ve read in ways that are amazing to me—they can integrate their reading and build a massive structure in their minds.

I’m not like that, and I’ve stopped trying to make myself be like that—it’s just not how my mind works. So I’ve evolved some methods for how I approach reading and absorbing the information I need to stay up on developments in my field.

First off, some of the things that I have to do on a regular basis, just as part of my job, force me to keep up with a good bit of the current literature in philosophy. For example, I get asked to review publications for journals, and I read loads of applications for jobs and for grad school. That exposes me to a lot of work, without forcing me to make a reading task list for myself.

But for those times when I do have to deal with a list of reading I simply must get through, I’ve recently come across the ‘Pomodoro Method’. I think it’s hysterical that they actually call it a ‘method’, but I’ve started using it for reading—breaking down my reading into more manageable, relatively short time chunks—like doing reps in the gym. I find it really useful, and it makes reading less of a chore for me.

One of the toughest hills to climb in my field is when I have to familiarize myself with an area of inquiry that is entirely new territory for me. My approach to those situations is based on the fact that I realized early on that, for me, it’s essential to figure out—and fast—what the main intuitive problem is in that new area.

How I introduce myself to areas of thought that are new to me.

It’s rare that I branch out into a new area in philosophy, but when I do, I look for the work of scholars who give a really nice, clear statement of the essential problem.

I start out by searching in online databases for papers written in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, written by names I recognize. Chances are good that one of them will give a really good, succinct statement of the problem I’m trying to introduce myself to.

By the 1980s, philosophy had started to get a little too techie and folded back on itself. The publish-or-perish model in academia has had a really bad effect on writing in the field. But those older papers will give me what I need: a ‘cocktail party summary’ of a problem—one that would allow a person on the street to grasp the essential issue.

After I’ve digested that, what I do next is to sit down and think it all through on my own for a while. I need to figure it out for myself.

I have to chart my own mental path through new ideas.

If you picked up a calculus book and just read it from cover to cover, with a general feeling of understanding, the way you might read a biography—you wouldn’t actually learn any calculus. In order to do that, you have to work through all of the problems for yourself.

It’s the same with philosophy: I need to know where the intellectual obstacles, stumbling blocks, and puzzles are, and what shapes they take, by trying it out for myself. Only after I’ve done that will I go back to the wider literature and try to consume and understand it.

If I give myself time and space to familiarize myself with the topic, and develop some of my own opinions—now I’m interested. I know what I’m learning, and I know where to take it. I also know how to listen to people who disagree with me, or people who come up with different answers than I do.

A lot of other people seem to do it in the opposite direction—reading everything out there first and only then retreating to think on their own—but if I started out by trying to dive into all of the literature first, I’d be completely lost. Nothing would stick, and I wouldn’t learn anything.

In my work, each thing I do leads to the next one.

Here’s how I approach the writing process. The first thing I do is I make sure I always have something I’m working on. I try to always have at least one, if not two, works in progress which are about the size of a twenty-five-page paper.

I’m very grateful to be at the point in my career where this happens naturally. I’m often asked to speak or give colloquia—an academic conference or seminar—at various places. The very act of accepting those invitations gives me deadlines to work towards. In turn, those deadlines force me to figure out what I think about different things—and they give me the reason to commit work to paper.

When I’m in the process of putting together a paper, I never rush into writing prose. It takes self-discipline. It can be tempting to just jump in and start writing, but doing that can really hold you back from developing and exploring ideas the way you need to in philosophy.

If you do research in chemistry or neuroscience, you do your lab work and you collect the results. Then you think about your figures, develop the graphs and illustrations you want to use, and finally you write up your text around all of that.

Philosophy has something like those same stages, but it’s all done in prose. That can be very confusing, and extremely inefficient—when you start to write on a new project, it’s the ideas you need to get at, not their final presentation.

To make matters worse, if you’re not careful, you can end up fighting with the sentences and paragraphs you’re writing—they can get in the way and block you from getting to the actual structure of where your ideas should be going.

Everybody’s processes for writing are different, and I advise my students to use whatever methods work for them. Having said that, I think I have developed two unusual and useful strategies in my writing process, and I always share them with my students.

I take notes on my inner monologue as I compose my paper in my head.

When you start a new paper, you want some thesis that you're going to support, or some conclusion you're going to get to—then you want some arguments that will get you there.

I usually have at least an idea of the intellectual steps I think will get me to where I want to go. I’ll think, ‘If I had this axiom, and that premise, I think I could get to my conclusion…’

At this point, though, I don’t actually know those details yet—it’s way too early in the process. I have to take the time to think, testing and re-testing my path to a conclusion.

My method is to sit down and compose my paper—but only in my head. I’ll have a notebook out, but I don’t write down complete sentences yet—it’s more like I’m taking notes on a mental lecture I’m giving myself. I write down the main ideas and what is supporting them, and a general idea of how the arguments go, generating an outline on the page as I compose in my head.

When I get to the end of the paper I am writing in my head, I flip the page over, and start over. I do it again.

And then I do it again.

I’ll repeat the process until the outline I’m writing down doesn't change. My energy for writing creatively about philosophy comes in pretty short, hour to hour-and-a-half chunks. I might take three or four of those chunks to write and re-write an outline for a new paper.

Once it doesn't change—at least twice, maybe three times—then I feel like I'm finally ready to turn on the computer and start writing in prose.

After I go to prose, I make descriptive outlines of what I’ve written.

At some point in the process of writing the paper itself—after I have quite a bit of it composed in prose—there will inevitably come a point where I start to feel like I’m getting lost in my own text.

That’s when it’s time to take a hard look at the structure of the evolving piece.

My current way of doing this is by taking the text I already have, and working backwards from it to create an outline. I paste the entire text into a new document, formatted as an outline in my word processor, and then I just start carving away at it.

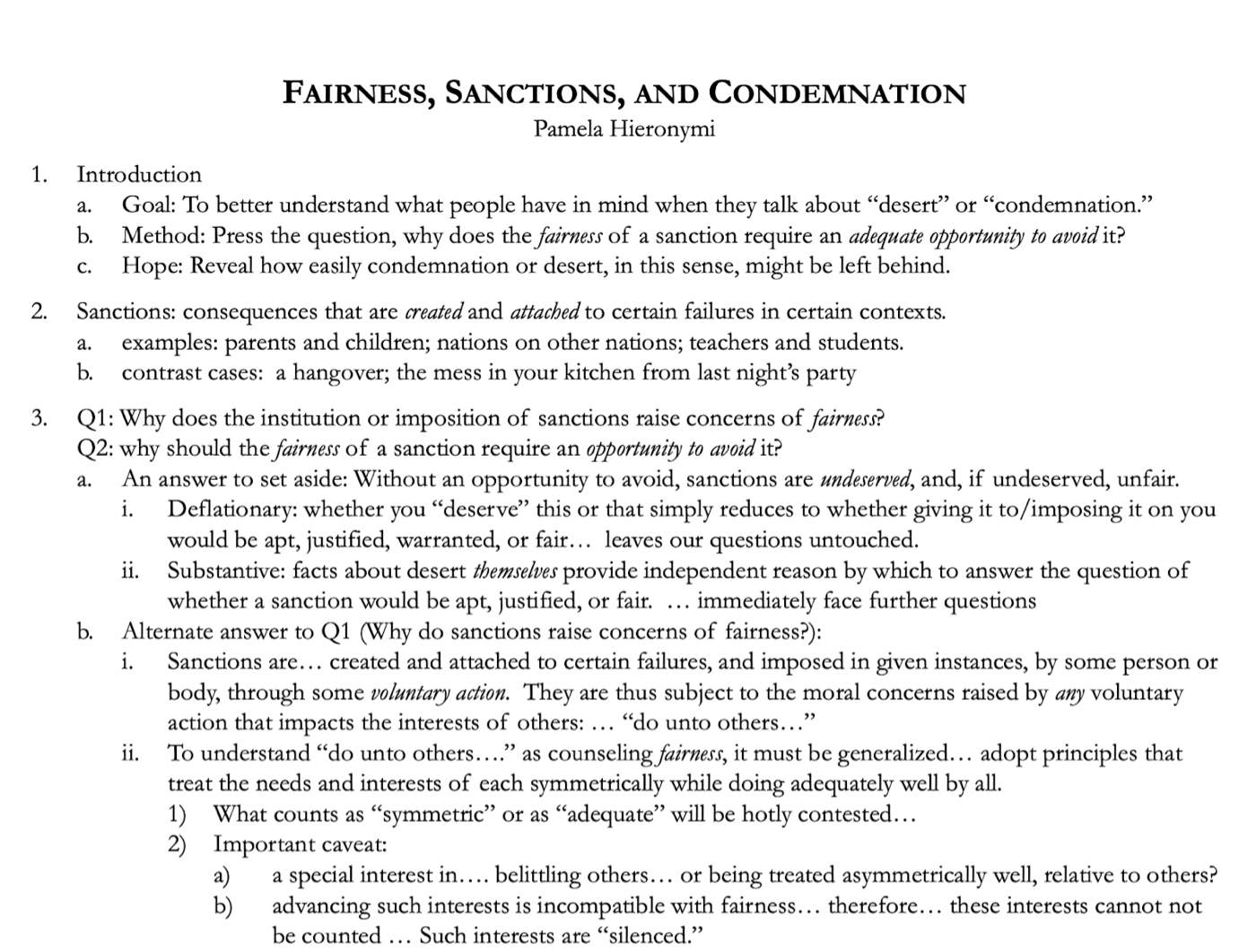

I delete excess stuff until I get down to a pretty dense outline—which will also serve as the handout I’ll use when I give a talk on the paper

That process allows me to see how the ideas are unfolding, what my main claims are, and where the main supports for my argument are. “What is this paragraph doing? Why is it here?” I can scrutinize the big picture and start to see where any major problems lie. I’ll move things around, delete unnecessary sections, and rephrase and reframe as necessary. This process of zooming into the detail of the prose and then out to the bigger structure really helps me to shake the ideas loose from the text, to make sure the text does justice to the ideas.

Only when that’s done will I move into the ‘journalist phase’—where I’ll go back and re-expand the clean, streamlined outline into a nice, polished final write-up in prose.

A Philosophy Book for the Road

Hey! Dan here again. If you're interested in reading more philosophy, one of the books that's cited in the show is What We Owe Each Other by T.M. Scanlon. It's a beast of a book, but an excellent example of how good contemporary moral philosophy can be. Check it out.

If you'd like to read something by Dr. Hieronymi check out, Freedom, Resentment, and the Metaphysics of Mortals. Or the papers on her personal site.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!