How Josh Kaufman Does Research

The author of The Personal MBA shares his process for finding answers hiding in plain sight

August 19, 2020 · Updated February 8, 2026

This piece was co-written by Dan Shipper and Natasha Frost.

For most of us, the world is full of questions.

For Josh Kaufman, it’s full of answers — if you know where to look.

His mission is to help his readers “upgrade the software in their brains” and he thinks that he can do that — not by discovering anything new — but by trawling through the vast academic literature that no one has time to read in search of the hidden nuggets of information that will be most useful to regular people.

He’s made a career out of it: turning esoteric research on everything from management to business strategy to learning into best-selling books like The Personal MBA and The First 20 Hours.

His job seems extremely fun: he has an unlimited book budget for himself, and he spends pretty much all of his time reading and writing. And over the years, he’s developed and improved a set of systems to help him conduct his research, find patterns, and churn out the books that he’s known for.

But it turns out that research isn’t just an academic exercise for Kaufman.

Ten years ago, he began struggling with a mystery disease — with a set of symptoms that completely mystified his doctors. Over the ensuing years he used the same research skills he built to write his books, to help track down and confirm a diagnosis — one that has helped to significantly relieve his symptoms.

So how does he find answers hiding in plain sight? Let’s dive to explore!

In this interview, we spoke about how he:

- Reads and processes so much research

- Uses two computers to make sure he can focus during his writing time

- Uses the “autofocus” system to manage his todo list

- Avoids burnout by varying the work he takes on

- Tracked down the diagnosis to a mystery illness that plagued him for years

Josh introduces himself

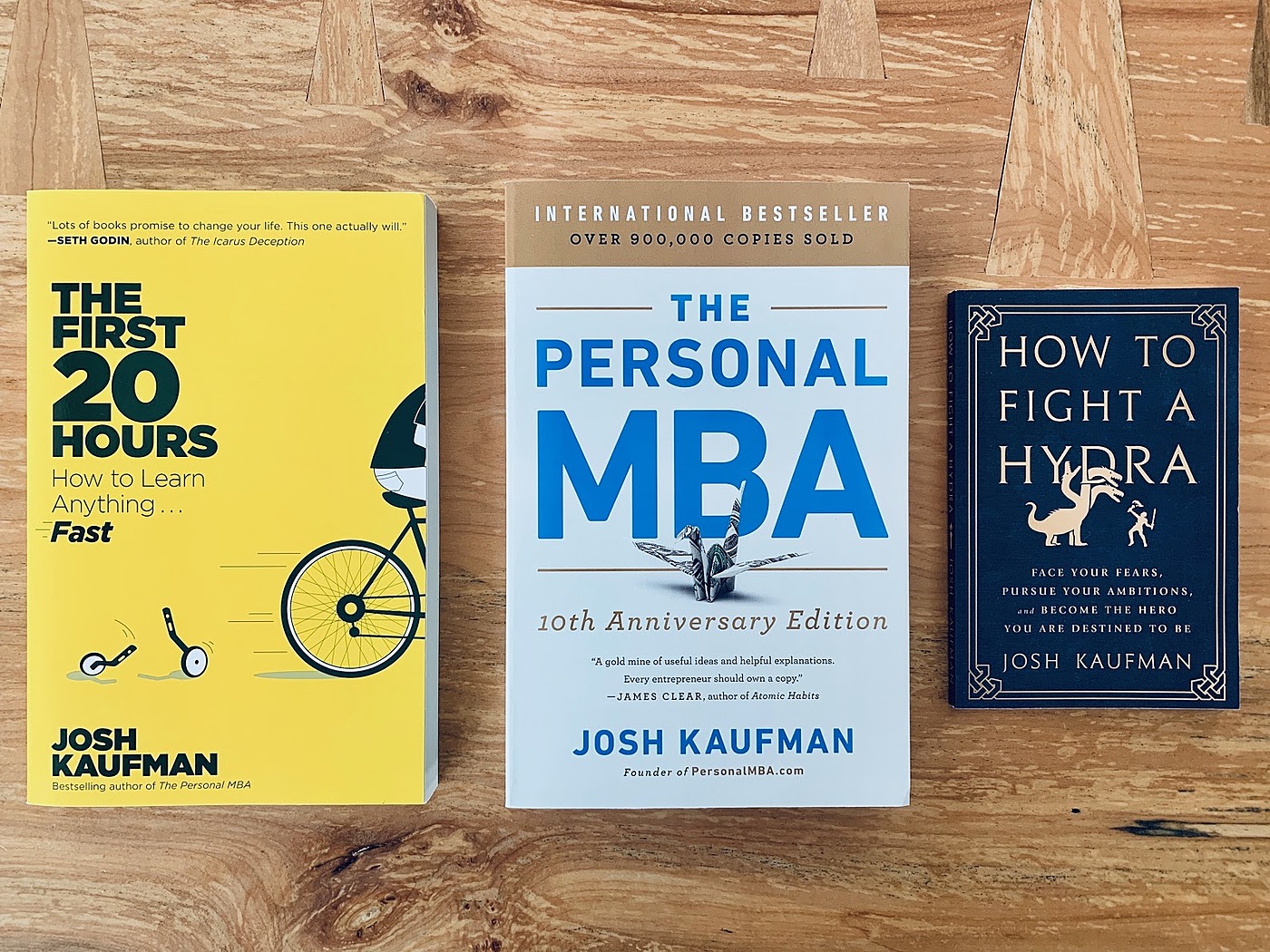

I write books about interesting and important topics that help people in their day-to-day personal and professional lives, including The Personal MBA, The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything… Fast!, and How to Fight a Hydra.

Before that I worked in brand management, product development, and marketing measurement for Procter & Gamble's Home Care division. I also advise business owners in industries from entertainment to healthcare.

These days, I am mostly working on practical and research-based approaches to making more money, getting more done, and enjoying daily life.

I hunt down insightful existing knowledge that people have forgotten or ignored

My job is to mine the literature in important areas of people’s lives to find more effective ways of solving or approaching problems that draw on this body of knowledge. The more reading I do, the more I’ve discovered that people aren’t typically paying attention to a huge corpus of pre-existing knowledge, often decades-old. I try to extract the best parts of it, and distill how people can apply that to their lives.

I like to think of it as upgrading the software in people’s brains. This means helping them to understand what they want, align their values and objectives, create a solid strategy to get it, and stop doing all things that get in the way of better results.

I read constantly, with rules for how I organize and digest different kinds of books

On any given day, I’ll spend as much as 75% of my time reading. Any book within the wheelhouse of things that I’m interested in exploring goes straight into the Amazon shopping cart and is on my doorstep in a day or two.

I have an unlimited book budget, and an overflowing library, as a result. When we lived in New York City, the walls of our 340-square-foot apartment were lined with books. When my wife and I built a new house, we put in massive, built-in bookshelves. Those books are sorted alphabetically, by title. In our kitchen, however, my wife likes to organise cookbooks by color, a minor crime against humanity.

I also have rules about how to read fiction versus non-fiction. I typically listen to fiction as an audiobook while washing the dishes or doing something else. But for nonfiction, I prefer sitting down with a physical copy to absorb the information.

I start every non-fiction read by scanning the entire book in 10 to 15 minutes, starting with the table of contents and index, to get a gist for the author’s argument and important concepts and themes that come through in headlines and call-outs. In my heaviest reading period, when I was putting together the Personal MBA reading list, I would preview 10 or 15 books a day this way.

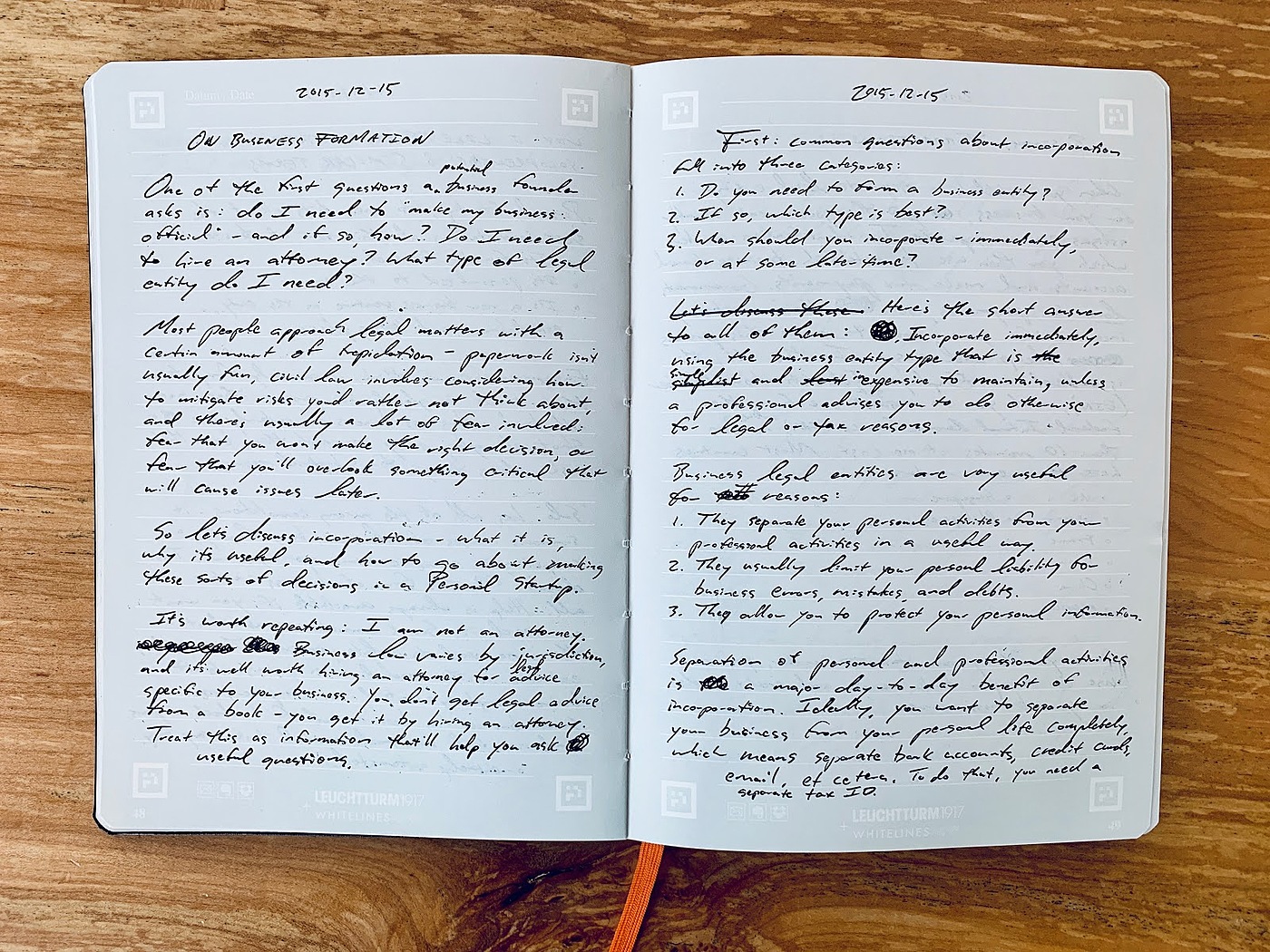

When reading physical books, I take handwritten notes to organize my thoughts

Another benefit of using physical books for my research is the handwritten notes I keep in notebooks, which form the backbone of my writing. I date every note I take and use them to check quotes or references. The system also helps me retain the information better. (Read more about that here.)

When I am really wrestling with a deep read of the text, I might write so much that I move to a small notebook or pile ideas into a few long-term research documents.

I often write the first draft of books and essays by hand. That may not seem efficient, but formulating abstract concepts across industries, markets, life situations, as I do, requires a mental workout with the material that I can only achieve on paper. I try to transcribe my drafts and notes as quickly as possible to make a backup, edit the text, and organize it into the overall structure of the finished work.

When it comes to online reading, I use electronic note-taking tools

I save the things I read online, too, in a digital research library. I’ve long used Evernote to clip the full text of articles I find and gather them in various digital notebooks, separated into categories for easy reference. I can full-text search everything that I've saved over the past decade, to find the citation really quickly. The combination of my physical library and my note-taking softwares act as a kind of external brain—in other words, my memory gets me to the original source of what I’ve read by searching my notebooks, Evernote, or Pinboard.

Recently I’ve been migrating this clip-taking to Pinboard, inspired by a Superorganizers post. Pinboard is much like Evernote, but allows you to tag clipped articles into multiple categories. Pinboard automatically saves a full-text version of each page you clip, so you can search and reference the text even if the website is removed or the page is no longer available.

I also use electronic tools to transition from reading and processing to drafting

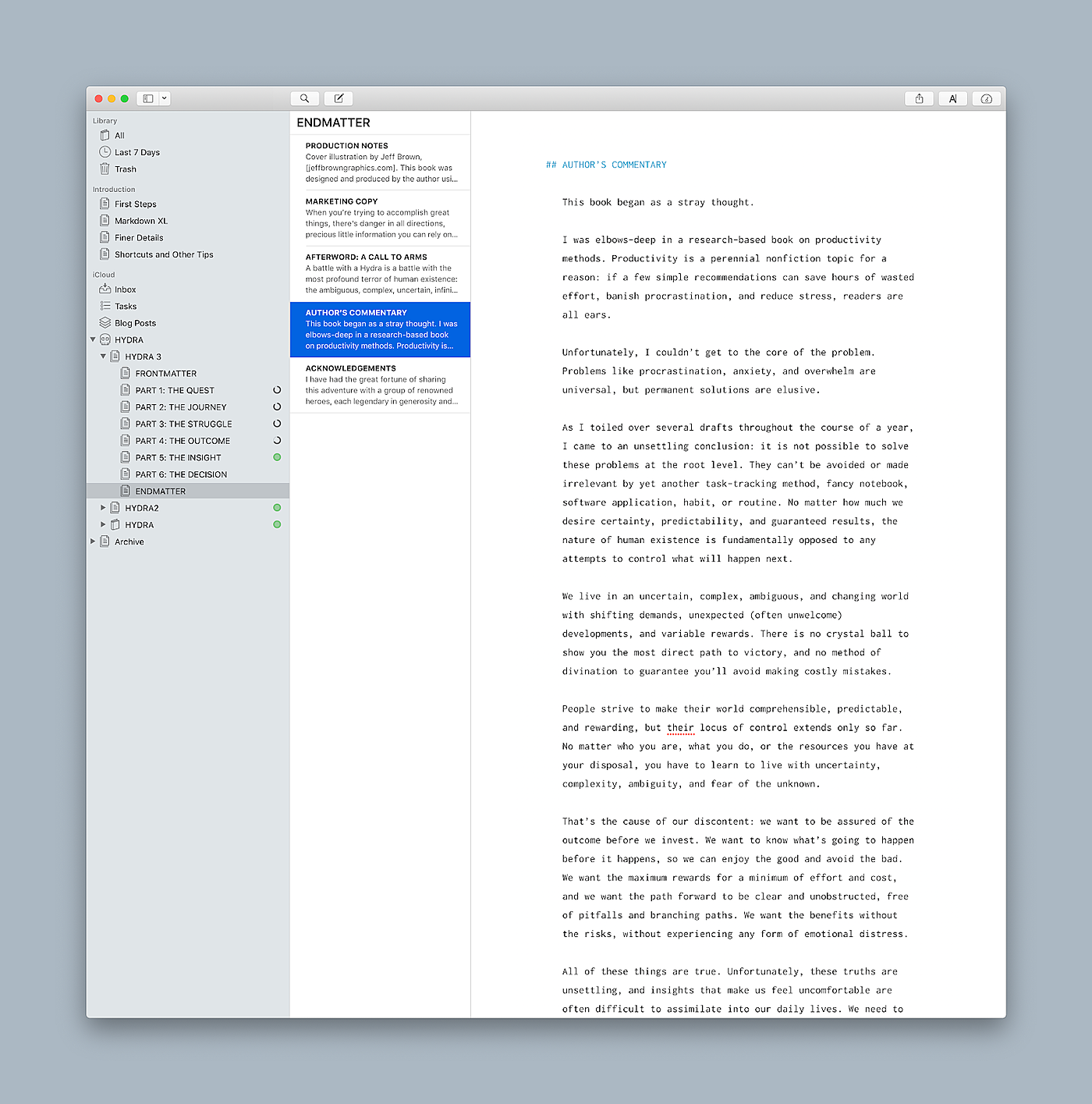

The drafting process is always the most painful part of writing for me. You have to synthesize a lot of disparate pieces of information and then translate their meaning for other people. To facilitate this process, I use a writing application called Ulysses for breaking information up into chunks I can easily move around. It uses numbered cards that you can rearrange or group.

I group my cards into the individual chapters, and keep an archive of the dead versions of my drafts. I'll just throw everything into whatever chapter format works for me, then go through multiple iterations until I get to the end result. It’s been a pretty consistent system for writing across my books. For The Personal MBA, Ulysses helped me transform my initial draft from a traditional longform nonfiction narration to one composed of many small chunks in organized chapters.

This is my Ulysses setup for How to Fight a Hydra. In the sidebar, you can see my three working drafts of the book. My archive of past projects is below the active title, so I can keep them out of sight and avoid cluttering the workspace.

If I’m not working with a large publisher, I have my own editing and publishing toolchain that I whipped up in Ruby, which turns Markdown manuscripts (a common formatting language for plain text documents) into finished PDFs in about 20 milliseconds.

Separating tasks across two computers helps me focus

To keep my writing process separate from the distractions of day-to-day life, I have two computers, one for writing, and one for everything else. I've learned over the years that my biggest enemy when it comes to writing productivity is the internet. It often feels like I’m trying to absorb every webpage on the internet through my eyeballs, and that's just draining. That’s why I have an office computer, with Safari, email, and everything else—and a writing computer with little beyond a word processor and software for focused tasks like screencasting and video calls.

My writing computer is as locked down as I can possibly make it. I even tried to uninstall Safari entirely, which was only marginally successful—it's built in there pretty deep. When I’m working on a writing project, I’ll sometimes find a point where my brain gets tired and I bring up Twitter, or something like it, just to have a mental break. Putting up as many barriers to that happening as possible is definitely a trick that I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of over the past decade plus.

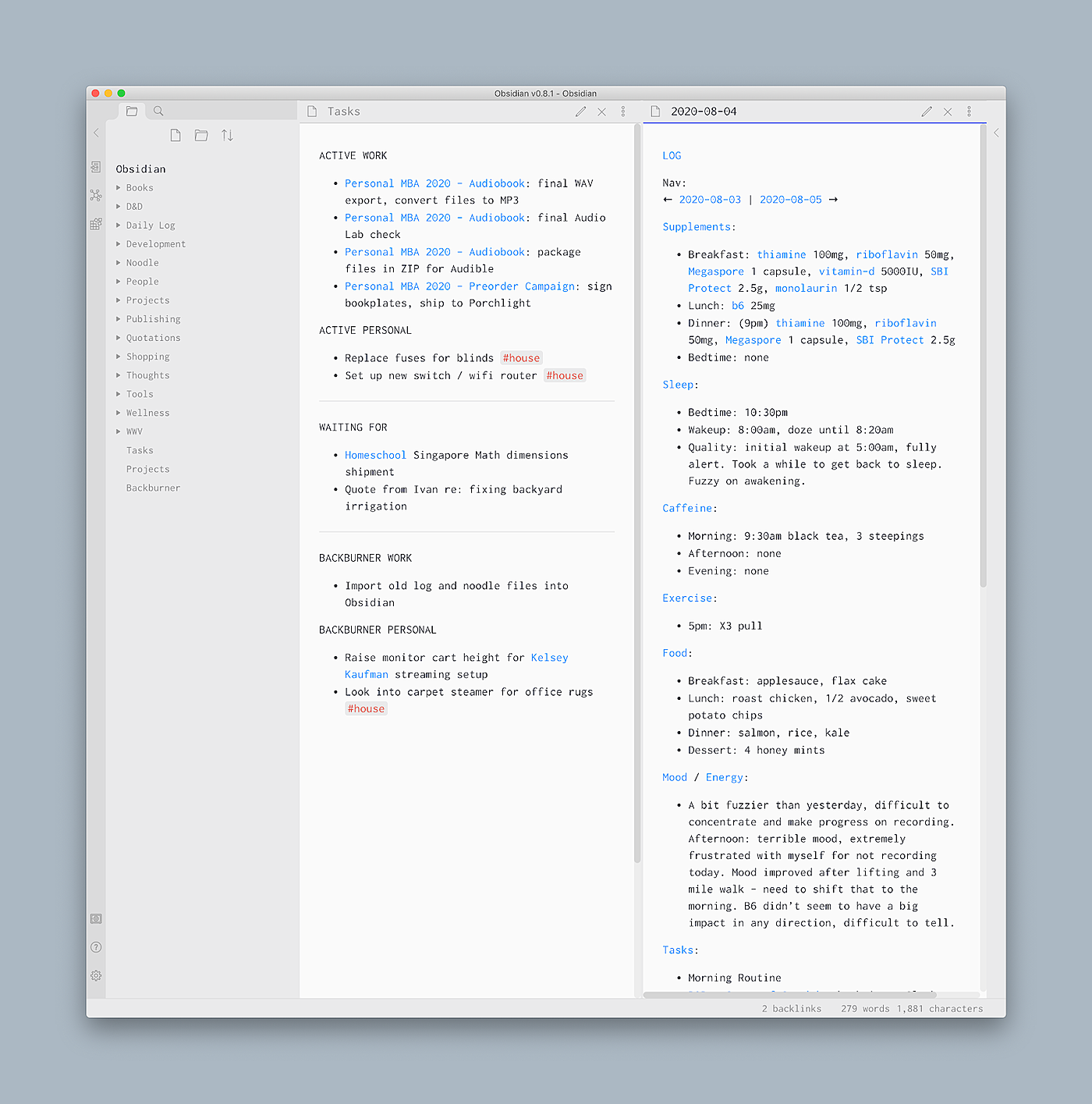

I use the autofocus system to help me get my tasks done

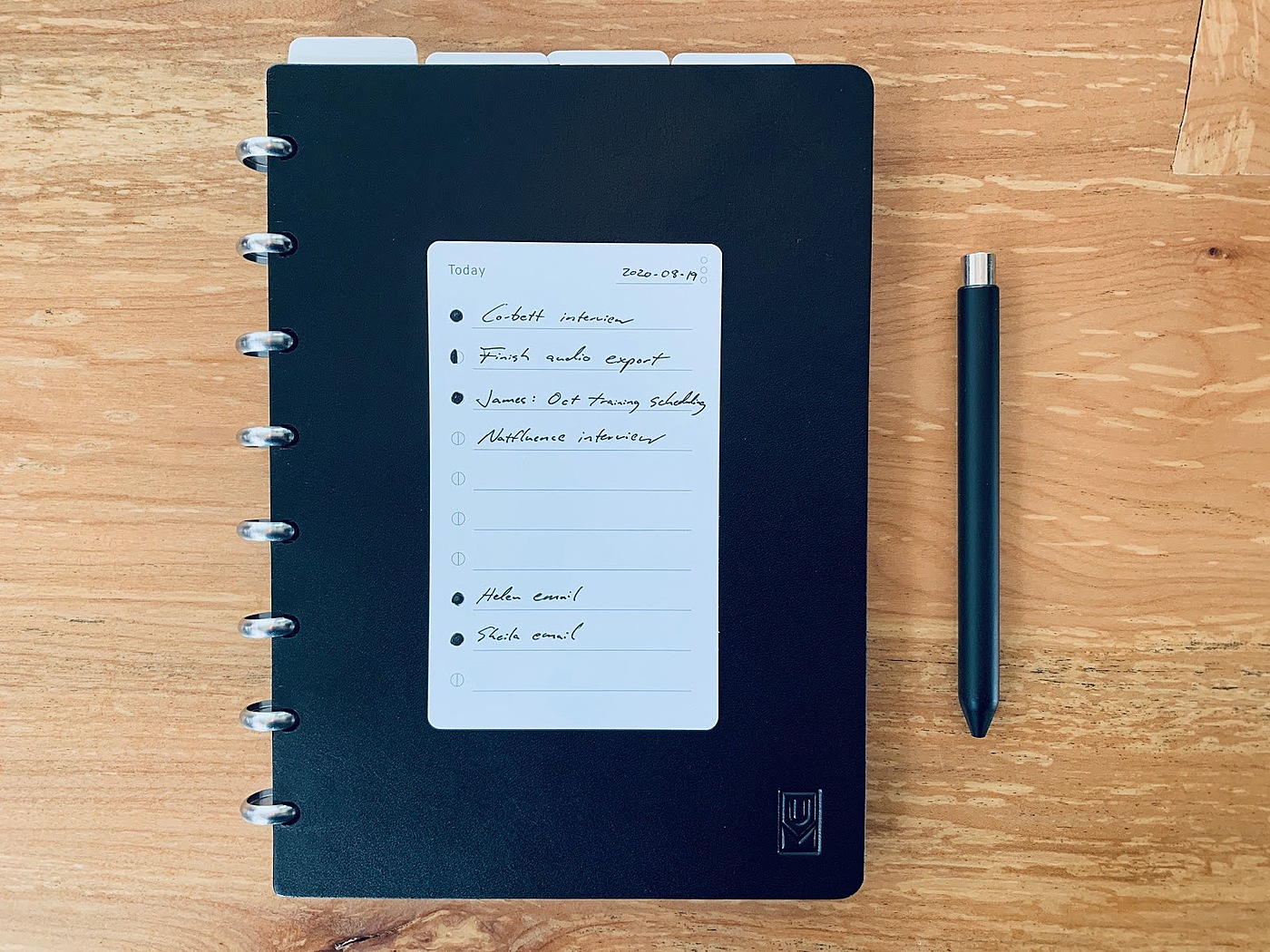

The problem with the classic to-do list is that it gets unmanageable. You can't find anything, things just keep adding to the bottom, you feel super exhausted and overwhelmed with all of the things that are yet undone. For years I’ve used the autofocus system of Mark Forster, a British time management author, to help me solve this.

The basic gist of the system is this: I keep a bulleted list of every task that comes up over time. I keep it as a text file on my computer. But you can use anything — it’s just a bulleted list. The list is long and disordered and most things aren’t done. Whenever something new comes up that I have to do I just append it to the end of the list and forget about it.

Then, every day I scan through that long list and pick out three or four things that I’m committing to doing that day. This is what I call my “today” list, and I keep it on a three-by-five note card that I carry around with me. The things on this notecard are the only things I need to worry about for the day—I can leave behind all of the other stuff on my plate.

If I get all of those things done, then great, I’ll just refer back to my bulleted list and add a couple more things to the notecard.

I keep a daily list of everything I get done, to reward myself and test my goals

Over the years, I’ve also kept a dailylog. Think of it as your “done” list, instead of your “to-do” list. The list is just bullet points—not what I planned to do, but what I actually did that day. It doesn’t matter if those things appeared on my to-do list at the beginning of the day. It’s where I put order numbers when I buy something online, where I log any sizable commit I make in programming, or feature I add to a project I’m working on.

It’s a good way to measure whether what you did is actually aligned with your goals and priorities: If not, you should probably change your approach. But it also gives you credit for things you did that you couldn’t plan for, like caring for a sick child. It may not reflect how the to-do list looked at the beginning of the day, but it’s still progress, along different parameters.

Finally, I keep a “noodle” file as my “want to come back to it later” file. It’s where I put notes for blog post ideas, my Dungeons and Dragons campaign, and so on.

Switching up the kind of work I do throughout the day helps avoid burnout

Staying productive in research and writing requires stepping away. Writing all day, every day, isn’t sustainable. If I were writing 24/7, I would get so burned out and depressed that my productivity would nosedive. I can focus on writing for 3-4 hours per day. After that, the quality of my work suffers.

Balancing different kinds of work can help people be more productive. You often hear stories of legendary people working 18 hours a day, every day. But often they were juggling many different things, which is good because different tasks require different kinds of mental energy. It’s much easier to work for that long if you’re bouncing between different types and modes of work.

Luckily, in my work life, the mental energy and focus that's required for research is very different from what's required for writing or programming. I find that when I shift between those modes of work—having a research project turned into a writing project, or taking a break from writing by doing a programming project—I create a flow that is much more constructive.

Signs my research process works: I used it to identify a mystery illness

The culmination of honing my research skills is the work I’ve done to diagnose and overcome my own health crisis. For over a decade, I’ve struggled with a mystery illness that left me exhausted and stumped my doctors. I finished the research process for a book, then found myself caught between exhaustion and severe fatigue, and barely able to sit down and write. My energy and mental capacity was extremely limited, and my usual standard of work was suddenly—full stop—not available.

I went to a series of doctors to try to figure out what was wrong, but no one could tell me what it was. It was a complete mystery.

That’s when I started researching.

I used PubMed, an excellent, searchable database of biomedical literature, to help me find any studies that were relevant to my condition. I also used DeepDyve, a great subscription service that basically gives you full access to thousands of academic journals, with a certain number of downloads every month. I’ve used it for every book that I've worked on, aside from How to Fight a Hydra.

The process took a long time. I spent many years researching, trying to form theories of what was happening to me, and then running experiments on myself to gather data.

I probably drove a lot of my doctors nuts, but it was really helpful to explore it from a data-driven perspective. I’d come to my doctor and say, “I have new data, I have a hypothesis based on this data, here are ways we can test them, this is my preference, is it a workable approach?”

I used the same kind of log for my medical research as I do for my book research. Any time I came across anything interesting I’d write it in my log with the date and use it to track down possibilities, form hypotheses, and come at it from a bunch of different angles. The goal was to gather as much information as possible.

Below is an example of my Daily Log and Task List which includes a combination of work information and health tracking data.

It took a long time, but it worked. We figured it out very recently, and I just started treatment. It turned out to be a rare inflammatory disorder.

When you have the flu or a really bad cold, your body tells you to curl up on the couch with a blanket and do as little as possible, to help it conserve energy to fight the infection. It’s a very well researched phenomenon known as “sickness behavior,” and very difficult to ignore when you have it.

My inflammatory disorder basically triggered that response 24/7. But when you take certain drugs and supplements that bring inflammation down, that stops happening, and I experienced a substantial improvement in energy. I’m not yet back to 100%, but I’m getting there, and it’s a huge quality-of-life improvement.

My personal life has taught me everything about the meaning of productivity

If productivity helped me solve my mystery illness, my mystery illness helped me better understand productivity.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve thought a lot about how productivity isn’t about checking everything off your to-do list—that’s an unwinnable race. It’s about deciding what's important to you, your values and priorities, then directing your time and energy at those things as much as possible. By the same token, you should minimize spending mental resources on things that aren’t important to you.

My mystery illness put a stop to my poor work habits. Adjusting required a psychological and emotional shift: My 500 mile-long to-do list had to be whittled down according to what my body could tolerate. In turn, I’ve changed my thinking from “how do I get through this massive list of things” to “what’s the best way I can invest my energy, capacity, and attention today.”

Another event contributed to this shift in productivity: Ten days after The Personal MBA came out, my daughter was born. I had to stop being a night person, who would collapse after writing until 3am, get a few hours of sleep, and do it all over again. With kids in the picture, that schedule is non-functional in every way.

These two very personal changes in my life revealed why I do what I do. The first is to help people learn things that will improve their lives in some way. The other reason I do this is because it helps me spend time with my family: Kelsey, Lela, and Nathan. If I’m short-changing that, I'm short-changing a huge priority in my life, and that's not okay.

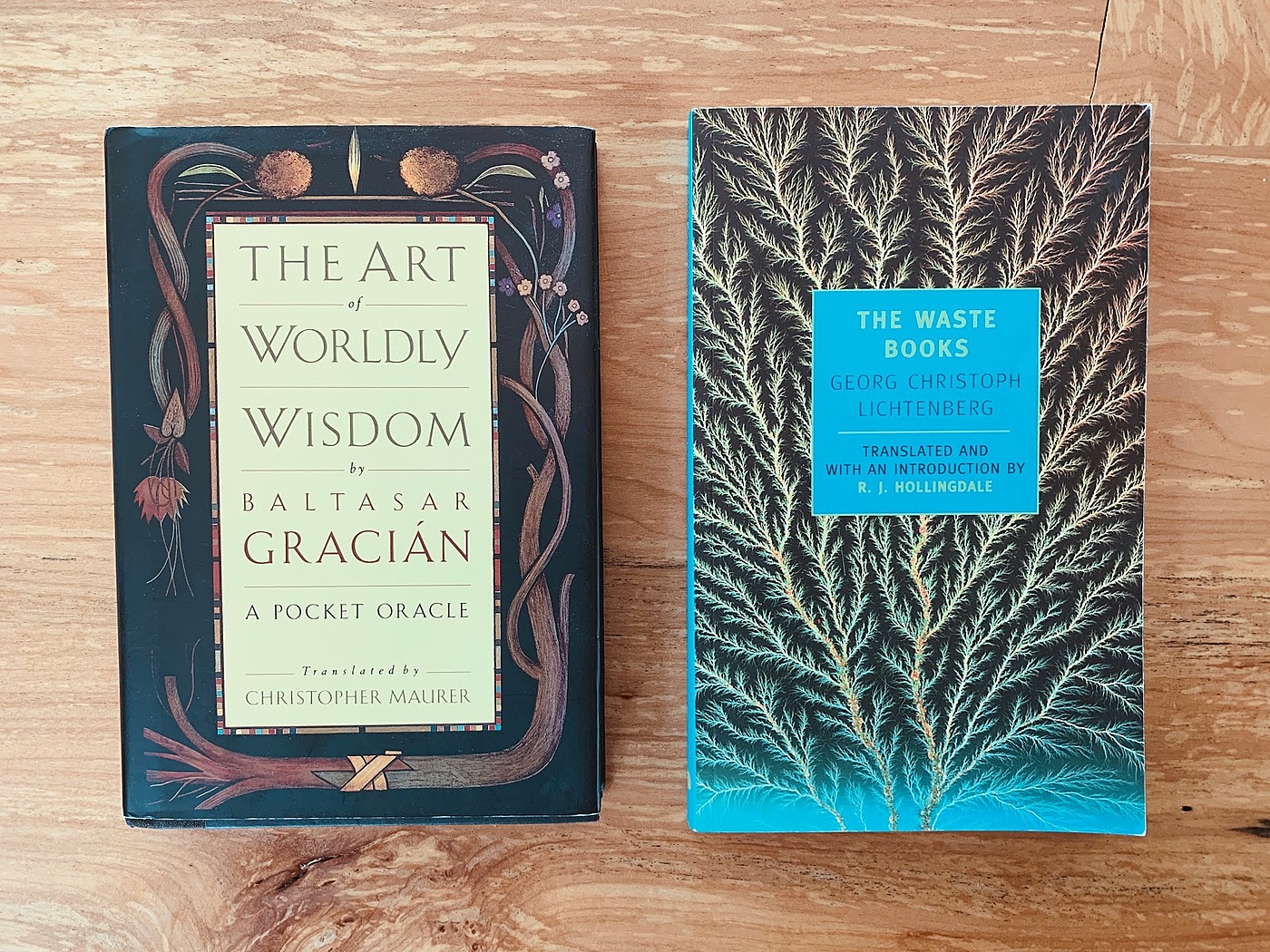

A Book Recommendation

When I just want to sit down and read something short and thought-provoking, there are two books that I keep coming back to. The first is The Art of Worldly Wisdom, by the 17th-century Spanish Jesuit priest Baltasar Gracián y Morales. It’s a very thoughtful, perceptive study of humanity that’s truly fascinating.

As a companion book, or series of books, I love The Waste Books, by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, an 18th-century German physicist. Similarly, it’s someone writing primarily for himself, making observations about how the world works and reflecting on his personal experiences, with a philosophical “this is how to do it better” bent.

This piece was edited by Roya Wolverson.

What did you think of this article?

NEW for You: Means of Creation

The Everything bundle welcomed a new newsletter today! It’s called Means of Creation and it’s all about the passion economy.

It’s a weekly talk-show where Li Jin and Nathan Baschez interview a guest to unpack the passion economy. Bundle members can watch and ask questions live as well as read breakdowns from the show as a newsletter.

Want to make this interview more actionable? Consider becoming a Superorganizers member through the Everything Bundle:

We’re striving to make Superorganizers Premium everything you need to live a productive life.

When you become a member you’ll get:

Superorganizers comes as a bundle, so when you subscribe you also get access to 4 other paid newsletters: Divinations, Praxis, Napkin Math, and Means of Creation.

Can’t afford a subscription for any reason? Send us an email and we’ll work something out!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!