Sponsored By: Graft

This essay is brought to you by Graft Workplace Search. Sick of spending valuable time searching for the right information? You're not alone. Employees lose nearly 20% of their time on this task, amounting to over 9 hours each week. But with Graft Workplace Search, your team can stop wasting time. Click below to learn how!

David Perrell will be a guest on Dan’s podcast, How Do You Use ChatGPT?, in early 2024. As a prelude, we’re re-publishing this illuminating interview with him about his writing process. —Kate

How do you find something interesting to write about? Put another way, how do you make your writing interesting? David Perell knows.

If the internet is a great online game, Perell is one of its grand warlocks. He’s fashioned a career as “The Writing Guy,” writing essays, building a popular podcast, and creating the premier course on writing on the internet, Write of Passage.

To make his writing interesting, he relies on an ingredient known as surprise. He wraps surprise into each sentence of his essays. He gathers it by constant searching, and he searches by echolocation. He throws out his verbal candidates in conversations and on Twitter at a prodigious, unrestrained clip. He’s looking for ideas and ways of expressing them that raise eyebrows, that generate so many reactions they can’t be ignored.

Perell is a small investor in Every, so it should be said I have reason to be impressed by him. But it’s not just me—Perell is deeply influential. If you read this article closely, you’ll hear echoes of David’s system in the approaches of other writers like James Clear and Robin Sloan. There is much about it that I—we—can learn from.

In this interview, we trace the birth of his mammoth essays from start to finish. We discuss how he gathers bits of surprise—from books, podcasts, strangers—in his notetaking system, Evernote.

We hear how he tries his ideas out in conversation—with friends, with students in his course, with random people he meets at parties. How he tweets them—irreverently, intuitively, instinctually off-schedule, whatever comes to mind. And we see how the ones that stick and stand out become his building blocks. When he sits down to write an essay, he has the raw ingredient of surprise at his fingertips, and his task is to harness it to express a larger idea.

When Perell writes, he’s “looking for the simplicity on the far side of complexity.” In this interview, we trace how he finds it. Let’s dive in.

Sick of spending your valuable time searching for the right information?

You're not alone. Employees spend nearly 20% of their time hunting for internal information according to a McKinsey report. On average, that’s 9.3 hours per week!

Designed to function like a Google search for your company's knowledge, Graft Workplace Search integrates effortlessly with your team's diverse tools and applications, including Slack, email platforms, internal databases, and more.

With Graft Workplace Search you can:

- Spend less time finding information, and more time ideating, creating, and innovating.

- Remove roadblocks to internal insights that would otherwise obstruct cross-functional collaboration.

- Cultivate a culture where answers empower employees rather than one where questions lead to dead ends.

Explore how you can leverage workplace search to boost productivity, fuel innovation, and drive better team outcomes, one search at a time.

Using live conversation to cull and test out ideas

I'm David Perell, and I'm a writer, a podcast host, and the creator of a writing school called Write of Passage.

Before I write my essays, I talk through them live in conversation. As I talk, I pay attention to how people react. Are they confused? Bored? Am I saying something insightful, or surprising?

These aren’t formal interactions that require structure or preparation. Instead, I’m talking casually with people in my life whose judgment I trust. These are people I feel comfortable sparring with, whether over a meal, on the phone when I’m out on a walk, or even on my podcast. It can be a family member, an old friend, a co-worker, or someone I click with at a dinner party. I devote a lot of time to cultivating these connections because they’re people who know how to push my thinking. And they usually exhibit two qualities: a sense for what’s interesting and an ability to ask revealing questions.

I listen for a few things in their responses. I have an acronym to help me keep track: CRIBS, which stands for confusing, repeated, interesting, boring, and surprising. When an idea I have is confusing, repeating (something I or someone else has said before), or boring, I move away from it and focus on other lines of thinking. When people find something I say interesting or surprising, I know to take that idea seriously and dig deeper to get to what’s insightful. This habit has become so ingrained that often I don’t even notice I’m doing it—I’ve trained myself to have a heightened sense of awareness of how people react.

Paul Graham likes to say that an essay should meander toward surprise. I take that to heart in my writing. I try to build up surprise, because surprise and insight and entertainment are all very tightly correlated. Surprise is also the fundamental axiom of Claude Shannon’s information theory. The more surprise in a message, the more information it contains.

Using Twitter to validate ideas

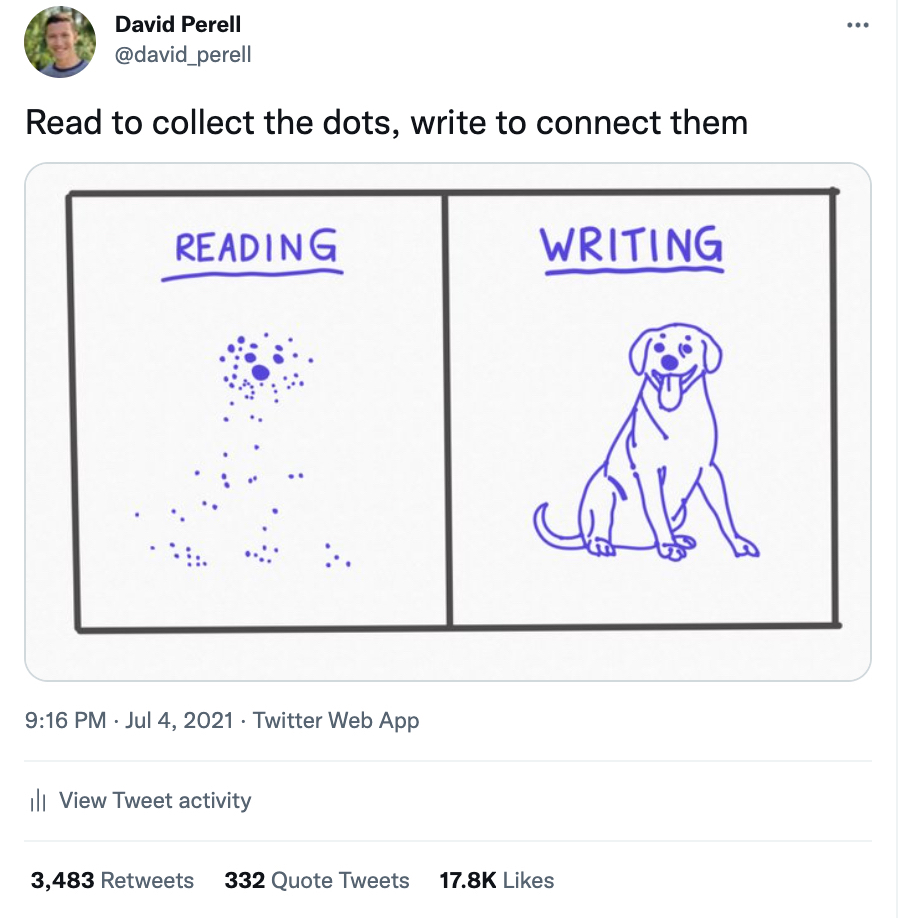

Twitter is another way for me to gauge people’s interest in ideas. Some writers are more measured in what they tweet and how they share their thinking. They might only share their finished work, or other published pieces they find interesting. I’m more playful and experimental with my tweets. I throw out all kinds of tidbits to see what resonates. It can be a quick chart, a drawing, or a simple writing tip I discover while sitting at the computer. The ideas behind the tweets may seem small or incomplete, but there is always a thread of insight that fits into my tapestry of ideas.

I pay a lot of attention to how people respond to these snippets of insight—even more so than when I tweet a long piece that’s taken me months to complete. It’s nice to get feedback about my larger essays after the fact, but it does less to guide my thinking about new ideas.

The snippets require less effort to produce, and I can immediately see if they pop. When something resonates, I might get hundreds of retweets, comments, and likes. In some ways, that makes Twitter a more powerful feedback loop than real-life conversations. Talking through ideas generates a trickle of questions and reactions, one person at a time. On Twitter, the response to ideas is immediate and plentiful.

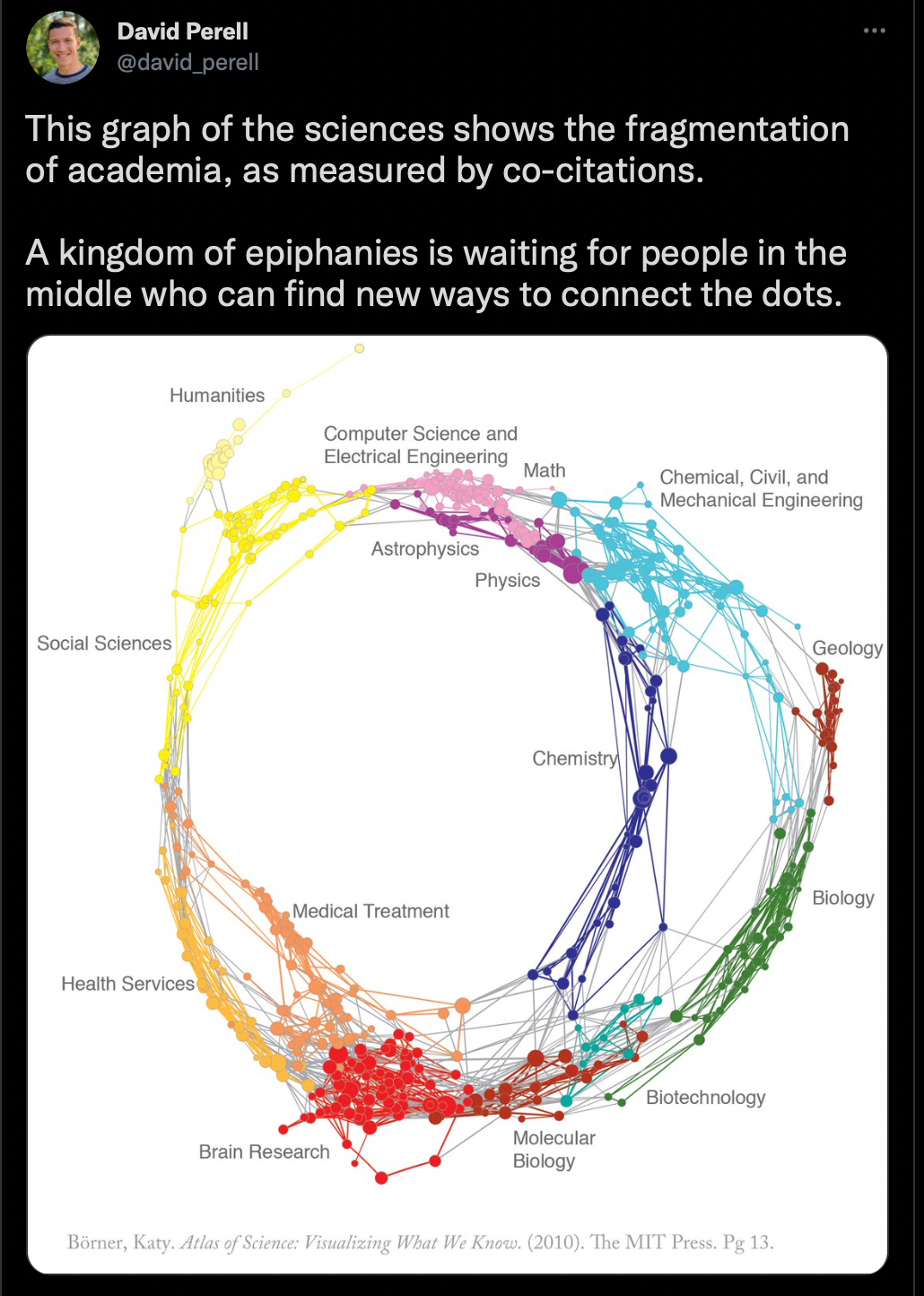

For example, I posted this graphic I found in my Evernote that explains the fragmentation of academia as measured by citations:

When I posted it, it popped—it got like 500 retweets. And I said, “You know what, I want to use this in some kind of future article—even though I don’t know what that’s going to be.”

It ended up in my ”People Driven Learning” essay. When I wrote it, I put it right at the top. And that worked really well.

Writing for 90 minutes every morning

At some point, I’ll realize that I have more good information than I could ever need about a topic to start writing. I usually have a sense of the essay I want to write, but actually putting the ideas on paper can be overwhelming. To overcome that feeling, I’ve established a strict writing routine.

Because I’m juggling a lot of projects between writing, podcasting, and my course, I have to be regimented and efficient with my time. Daily, I write first thing in the morning for 90 minutes, before I open email or check social media. I don’t have a word count I’m shooting for. I just focus on distraction-free writing. I like how Neil Gaiman puts it: "I think it’s really just a solid rule for writers. You don’t have to write. You have permission to not write, but you don’t have permission to do anything else.” Once my 90-minute timer goes off, I can stop writing whenever I want.

I always write on the computer at my desk with a big monitor. In the early stages of writing, I listen to big room house music or podcasts, like Group Therapy, to inspire ideas and get me into flow. When I’m editing, I’ll switch to more ambient music like deep house, which helps me relax and deepen my focus. For the final stages of my writing, I never listen to music.

I usually work on three or four essays at a time. That lends variety to my workload without spreading my efforts thin, which can be distracting and demotivating. I have to be excited about what I’m writing. If I’m forcing myself to write, then the idea is probably incomplete or not that interesting. You can waste a lot of time aimlessly researching and writing about a topic you feel iffy about. People can tell when writers are uninspired. The words feel hollow and the sentences feel lame. No matter how much rewriting or editing you do to try to improve it, in the end it usually falls flat. Because of that, I don’t have a content schedule. I just write what stirs my soul.

Sorting my notes into building blocks

For me, finding and testing out ideas is easy. Figuring out what to do with them is hard—so hard that if I’m not extremely organized about my writing process, I’ll end up with a crippling case of writer’s block.

To avoid this, I break my writing into finite chunks that make my essays feel more manageable. Sometimes, I’ll start by creating an outline to dump all my notes into. I create sections based on themes I pull from scanning all the information I’ve collected.

I think of these sections as LEGO blocks. Each one is like a mini essay that I can address without having to think about the rest. One by one, I condense information, expand on ideas, and cut what doesn’t work. As I work through each section, I discover and refine ideas that further my point.

When the blocks are completed, I figure out how they fit together. Not all of them do. I think of this process as a little bit like playing Sudoku. When you change one piece of the puzzle, you usually have to change the rest too. The whole puzzle needs to work together.

I end up with blocks of text at the bottom of my outline that don’t fit the narrative. If I’m wedded to those blocks, I’ll talk it out with people. If the blocks still don’t fit, I’ll save them in Evernote for future use.

I can’t claim that organizing the writing into LEGO blocks is the best solution for every writer or genre of writing. I just know that if I don’t use them, I can’t get through the work. Knowing that the ideas in my first draft don’t need to fit together perfectly helps me put ideas on paper. Once they’re on the page, no matter how messy they are, I can shape them into something I’m proud of.

Using drawings to help distinguish my essays

Words aren’t the only way I express ideas. Many of my essays feature drawings I create to capture essential points. The drawings have a particular style that helps distinguish the writing and elevate my thinking. Readers like them because they’re unusual and memorable.

I make these with an app called Concepts, and I create them on an iPad with an Apple Pencil. I pay attention to the colors I use to make each drawing recognizably mine. I use the same Purple (#5A44e4) to match the color of my website.

I want the drawings to look professional enough to show that I took some time on them, but playful enough to look human and relatable. I don’t want them to look too polished.

Writing is synthesizing complex thoughts

For me, writing is about finding the simple in the confusing and the elegant in the complicated. Technology has put an endless amount of information at our fingertips—it’s hard to know what to pay attention to. Good writing solves that problem. It takes the burden off the reader’s shoulders by whittling the complex down to the essential.

This isn’t an easy thing to do. You aren’t aiming for superficial ideas—you are trying to convey complex ideas simply and elegantly. That means wrestling with all the good ideas that are already out there to arrive at real insight. You accomplish that by absorbing a ton of information and stirring on ideas until they speak to you.

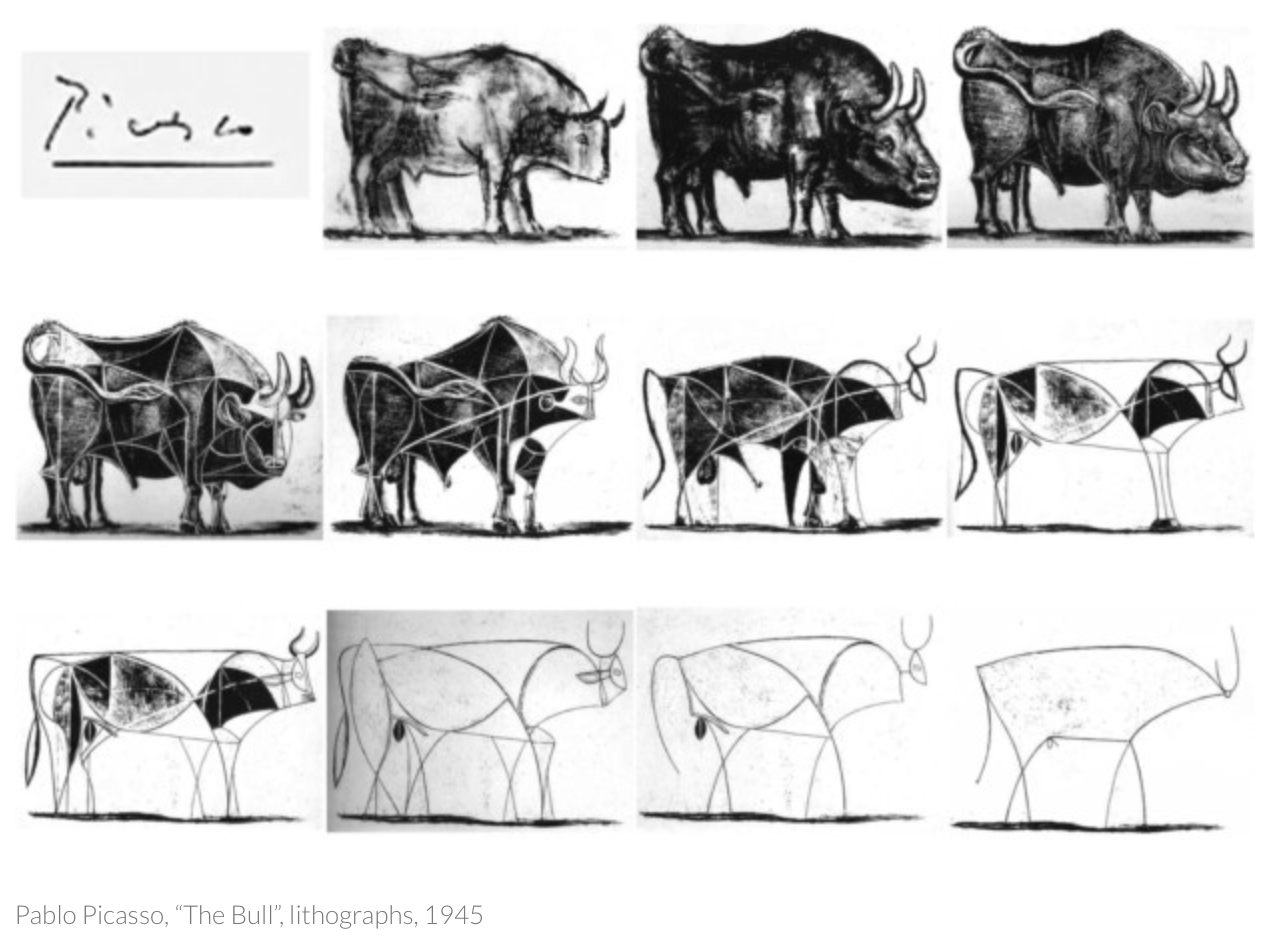

That’s when I start thinking about compression. Pablo Picasso’s iconic “Bull” sketches are a perfect illustration of this. In his series of 11 lithographs, Picasso adds more detail into each subsequent sketch of a bull. You see him expand on his own thinking. The first drawing is an intricate, realistic sketch of the bull. In the next two, he actually adds in more complexity. This is Picasso’s research phase.

As he sharpens the horns and adds shadow to the face, the bull becomes three-dimensional. He’s exploring possibilities and building on ideas. He’s shooting for more, not less. But there’s a point where he realizes it’s time to reverse course and rein the image in. He ends on a sparse but elegant rendering of the animal using just a few essential lines.

Where is that turning point for a writer? It comes to me late in my research process, when my head is so full of information that the urge to write overpowers me. My ideas may not be fully formulated, but I need to get them down on the page to know how to refine them. This is what Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. called the “simplicity on the far side of complexity.” I plow through several rounds of writing and editing to weed out the excess and focus my thinking. When the epiphany comes, I can’t help but write. It’s a magical feeling. It’s as if the idea becomes hyper-saturated, while the rest of the world goes black-and-white. And hopefully, by the end, I arrive at the essence of the bull.

Sharing ideas to create a virtuous cycle of connections and opportunities

When we reach the end—that essence of the bull—I’m always reminded of what draws me to this craft. It’s the intoxicating feeling of knowing that people will resonate with a good piece of writing. People worry a lot about the drawbacks of social media, but for a writer, its most salient feature is the ability to amplify good ideas. Under a long-time horizon, the internet is a meritocracy. The best stuff spreads. The better the essay, the more people will read, share, and talk about it.

This is so different from the experience budding writers used to have when learning the craft in school. You’d spend years pouring your time and effort into writing for a single person: your teacher. That’s nowhere near as exciting or rewarding as publishing your writing on the internet. So I’m not surprised when I hear people say they don’t like to write.

My writing is a beacon for new connections, ideas, and opportunities. Almost all my closest friends are people I’ve met on the internet. Reading somebody else’s writing is a great gauge of a person’s mind. It reveals how they think, what inspires them, and what they value.

Opportunities from writing crop up so often now that I’ve learned to think very carefully about which ones to pursue. I draw on Warren Buffett’s investing philosophy, which is to wait for the “fat pitch.” The stock market offers a world of enticing investment opportunities everyday, but you don’t want to jump on everything. Like a baseball player at the plate, you want to be selective about when you swing. When the right pitch comes, you should swing for the fences.

This post was co-written by Roya Wolverson.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This piece touched something in me. Insanely useful and inspirational! Thanks Dan, David, and Roya!