Imagine we found a way to turn stress on and off instantly without side effects.

Flick the switch on and you're Ken Lay sweating questions from the auditors. Flick the switch off and you're the Dalai Lama on vacation, baby.

If we discovered something like this, it would be pretty fucking cool. It might allow you to pursue a stressful career without exposing yourself to its negative side effects. It might allow you to have hard conversations with your partner without feeling overwhelmed and creating harmful negative loops that leave you both feeling worse. It might allow you to get on stage and give a presentation without feeling like you want to blow chunks.

It might literally prevent fights, bankruptcies, divorces, and wars. Because after all, the stress response is kind of like the Martin Shkreli of emotions: no one likes it. No one can defend it. It's just not that useful in modern society.

It was built to get us out of short-term physical danger millions of years ago. It wasn't intended to help us deal delicately with discovering that the dishwasher wasn't emptied after dinner last night. But it engages in the same way as it might if we found a lion in the sink rather than last night's cookware.

If I had the option to turn down my stress response in certain situations, I'd definitely take it.

That's why I was intrigued by Cove.

Cove is a gray wearable device that you put on your head. It reminds me of an Xbox Live headset without the mic, the Doritos, or the smell of teenage despair. It costs $490. It says that it can help you "conquer stress" and "sleep better."

In other words, it's trying to be the vision of the future we were just talking about. A way to turn down the stress response, to deal with the rigors of modern life better. And you don't need a pill, or therapy, or exercise, or meditation to do it—you just put the thing on your head and press a button and feel a little bit better.

Best of all, it says it's science-backed: "90% of Cove users experience better sleep and reduced stress after one month of daily use. These benefits have been validated by 4+ years of rigorous research, including independent studies at Brown University and the work of a leading researcher from Harvard Medical School."

90%! That's a big number. And I like the idea of rigorous independent research from Brown and Harvard.

After I came across it, I immediately wanted to find out more about this little device. But ye-gads! $490! That's a lot of dough. Fortunately, one of the best parts of being a Productivity Influencer(TM) is that the kind people at Cove were nice enough to send me one to review.

It came messengered from somewhere in Brooklyn in a matching Cove tote bag (nice!). Its box was Apple-inspired—a Cove-grey and green cube made of thick, matte cardboard that was slightly smooshed on one side.

I separated the Cove from its packaging and turned it on by pressing a button on the side. I paired it with my phone. I put it on my head and sat on my couch. I rubbed my knuckles and flexed my jaw to work out the TMJ that keeps them clenched.

The world wooshed and whirred around me as I pressed "Start" on the app. I prepared to conquer stress. Dalai Lama, eat your heart out!

.

The Cove works like this:

It has these large pads that sit flush with the bone-y part of your cranium right behind your ears. I don’t know what those things are called, probably something similar to whatever vaguely Latin words we’ve used to name the geological features on the dark side of the moon. The Deep Aural Mare, or the Montes Maxima Crania. Go ahead and touch your Montes Maxima Crania. Mine is a hard, solid bone that protrudes slightly toward the back of my ear.

That’s where the pads of the Cove sit, and they lie dormant until you turn it on. When you do, the pads start to vibrate in pulses. You can dial the strength of the pulses up and down using the app—up so high that the Cove makes your skull feel like you’re at the dentist for a nasty bit of carpentry, or down so low that the vibrations are barely perceptible at all. So low and smooth that they’re like little drips of water falling every so often into a cool, still lake.

You might imagine that with the Cove, as with everything else important in life, more is more. That if you really want to turn your stress response off you need to crank the intensity up to 12. But according to the manufacturer's instructions, the opposite is actually true.

The real way to dial in the Cove, and dial down your stress response, is to set the vibrations to be so low that you can barely feel them—but no lower. This is an intriguing thing to me, and it’s also sort of complicated to do.

I find that my sense of whether or not I can feel the vibrations varies very much based on context. If I’m looking to feel the vibrations, I’m more sensitive than if I’m concentrated on talking or doing some other task.

Do I need to feel the vibrations in order for it to be working? If I felt them at one point, but don’t feel them now is that a problem?

I really want to do this the “right” way, but the manufacturer provides no guidance about these sorts of philosophical questions. So I keep the Cove at 2 or 3 and keep my fingers crossed.

.

I felt better when I tried it for the first time. The vibrations produced a weird sort of flushed feeling in my face—like a blush but pleasant—that felt oddly relaxing, and protective. My stress, fear, and anxiety felt like they were on hold temporarily.

I felt a little sheepish at this. Am I just too suggestible? Or is this thing really on? But I also felt kind of awesome, like I had some weird quirky secret to a more relaxing life.

The first day, I wore it on calls, proudly showing off my Happiness Headband / personal cranium vibrator to skeptical onlookers. I explained the vibrations, and the way I was feeling.

But after a while it got uncomfortable. The headset itself is like a pair of over ear headphones: when worn for long periods that places it presses start to get sore. And the vibrations themselves started to get old. Like that feeling you get as a kid after the 10th Warhead. The first 9 are exciting, and new, and fun—but by the 10th your teeth feel brittle, your tongue is flopped pleadingly at the bottom of your mouth, and you’re reconsidering some of your choices.

I took off my happiness headset and resolved to try to understand what was going on. If this thing does work, why might that be? And if it doesn’t, why would I feel this way?

.

The science behind the Cove is simple: it stimulates your sense of affective touch to help you feel better when you’re stressed out.

Affective touch is the feeling of touch that gets activated when someone you know and trust touches you. In all sorts of animals, but especially in primates, this kind of experience can promote a sense of pleasure and well-being.

It makes good evolutionary sense! Animals that feel pleasure from affiliative social contact are more likely to have more of that contact, and thus to survive and reproduce than animals that don’t. So lucky us, most of us feel pleasure when we get touched. If you don’t, well, there’s always the pleasures of reading Continental philosophy.

I’m not saying that Schopenhauer never experienced affective touch, but I’m also not not saying that.

The interesting thing about your sense of touch is that it can be disaggregated into lots of different senses. You have receptors to know if the thing you’re touching is smooth or rough, if there’s lots of pressure or no pressure, if it’s sharp or blunt, if it’s hot or cold, and so on. Signals from the receptors get transmitted from the skin to the brain for processing. Your brain receives the signals (moderate temperature, medium pressure, soft) and decides, Skin, I’m touching skin, decides that’s good, and then releases oxytocin.

But it’s more complicated than that. There’s a special set of receptors called C-tactile afferents that are responsible (we think) for (at least in part) transmitting a positive affective valence of the touch experience to your brain. Basically what that means is when your CTAs get stimulated they’re not just telling your brain something like “there’s pressure here!” they’re also telling your brain “this feels kinda groovy!”. (Walker, et al., 2017)

There’s lots of hypotheses for why they’re built this way, but the most widely accepted one right now is that they’re responsible for picking up social touch—e.g. they’re responsible for telling you that you’re being touched by someone else that you like.

We don’t know this for sure of course, but there’s a lot of evidence for it: CTAs fire when your skin is touched slowly, without lots of pressure, with a neutral temperature, and the kind of touching that most stimulates CTAs is also the kind of touching that people report to be most pleasant in the lab.

All of those conditions are consistent with the idea that they’re used for social touch. But here’s where the plot thickens:

At least one study has found that this activation of CTAs is equally pleasant whether the thing that’s touching you is a human hand or something mechanical. In CT-optimized skin stroking delivered by hand or robot is comparable, the researchers found exactly that: when people were asked to rate the pleasantness of both human and mechanical touch that was designed to activate CTAs they consistently rated both as comparably pleasant.

And that’s where we circle back to the Cove. When the Cove’s pads sit on those bony bulges of skin behind your ears and vibrate, they’re theoretically activating your C-tactile afferents. That’s why Cove recommends that you set the vibrations to be just at the level where you can feel them and no higher. CTAs are sensitive little receptors, and if the vibration is too high they’ll stop activating.

When you activate those CTAs, it signals to your brain that you’re being touched by someone you love. And that’s going to feel pleasant.

To be clear: it’s not that this little plastic vibrator on your head is going to feel exactly like being touched by a human. You know the difference between being touched by a finger, or by a headset. It’s that your sense of touch has many different components, and one specific component is responsible for telling you whether or not the experience you are having is pleasurable and one you want more of. The Cove is specifically designed to activate that part of your touch experience, and therefore feel good.

The question is: is this actually what’s happening when the Cove vibrates?

Does the Cove stimulate affective touch?

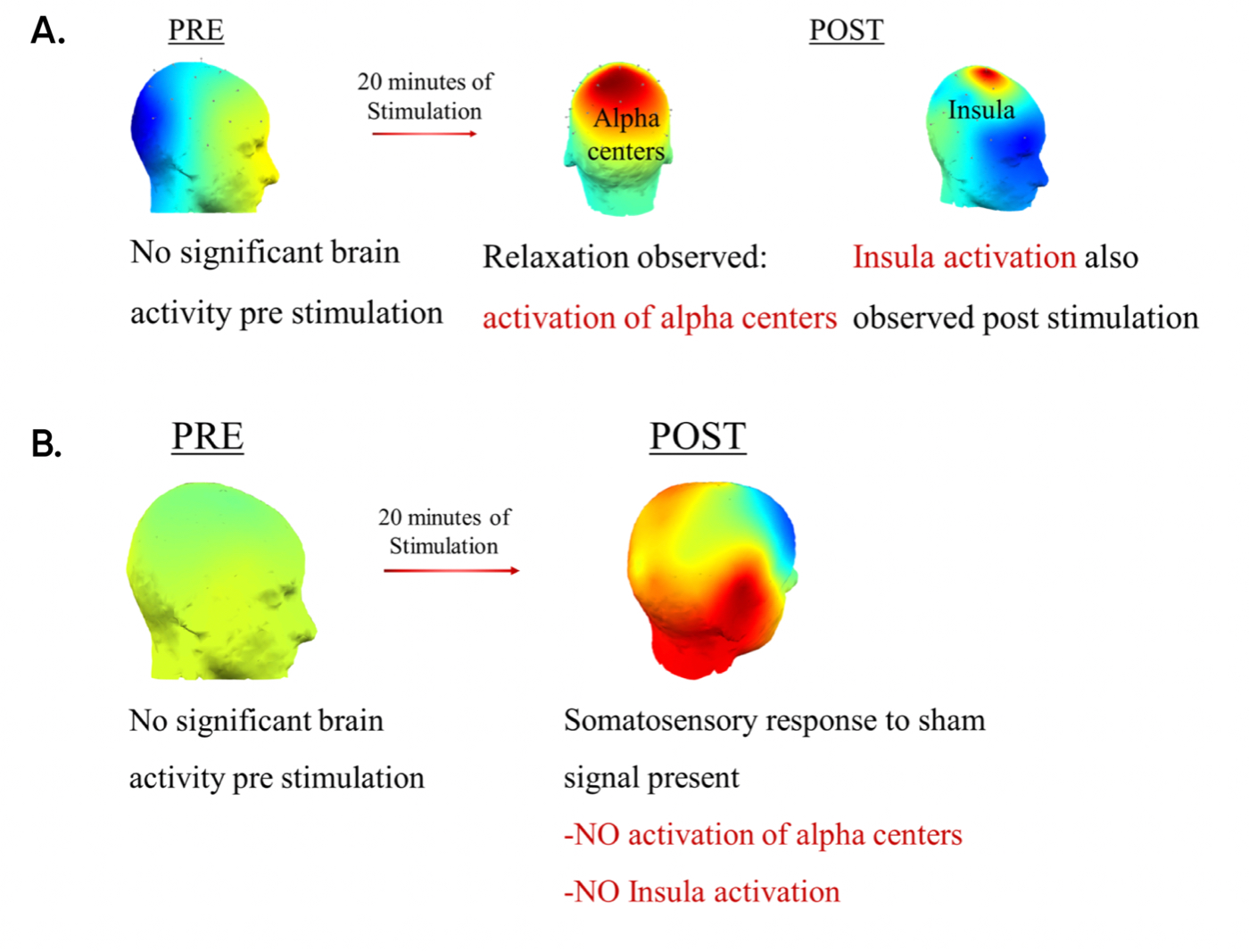

We know that the Cove is activating some touch receptors on your skin, but we don’t know that CTAs are being activated specifically. It’s actually really hard to know which nerves are getting activated from any particular stimulus so you need to infer activation in some other way. Cove’s way is to measure a pattern of electrical activity in your brain called “alpha waves” by using an EEG, and they also use self-reports of stress levels and sleep quality.

Based on my conversations with Cove, it sounds like they spent a long time trying out different vibrations, and they finally found patterns that seem to increase levels of alpha waves, and get test subjects to report it reduced their stress and improved their sleep.

Cove has a study summary on its website that says that over half of volunteers that tried the device show increased “activation of alpha centers” while volunteers who were subjected to a different set of vibrations did not:

There’s just one problem. In all my research, I’ve struggled to find any association between CTA activation and increased alpha waves in the brain. The closest I got was Wikipedia, which says alpha waves increase when we are in a state of “wakeful relaxation with closed eyes.” But then I found a study saying CTA activation (you know, the specific thing Cove talks about) is actually associated with lower alpha wave activation.

They do have other study summaries on their website. They did a test with a couple dozen people showing the Cove’s effect on stress and on sleep. But neither of the study summaries include data from controls so I find it hard to draw any conclusions about them. Basically in the studies it looks like they gave a bunch of people the device, and had them fill out questionnaires before and after that asked them about their stress levels. Many people, in response, said “I guess a little bit?”. But that’s not great evidence for much, in my opinion unless you can show that controls exposed to a placebo didn’t have the same reaction.

It’s actually pretty annoying. They talk about other studies on their website that have better designs—you know the ones done by Brown and Harvard—but they don’t share those. What they do share looks pretty shoddily done, and makes it hard to draw many conclusions.

So when it comes to CTA-specific claims, for now I give the Cove a big ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

All of this points to something important about devices like this: it’s just really hard to tell if something’s working, and if so how. The neuroscience is still really early, and it’s really difficult to study this stuff.

I’m extremely bullish on the category of devices like this. And I give Cove a lot of kudos for trying. It’s extremely hard to build a device like the one they’ve built, and I think in the years to come the science will be mature enough for the category to really help a lot of people.

But right now we’re flying blind when we build devices like this and try to explain why they appear to work, or not.

.

Okay, so let’s get down to brass tacks. Science aside, what was it like to use the Cove? It felt kind of like this:

When I was in college one of my friends scored a couple of small white pills with the Louis Vuitton logo on them.

We took the pills and fervently waited, hoping to go to a Basshunter concert as soon as they kicked in. Minutes passed, and we didn't feel much. A half an hour in, my friend Ronald (this is not actually their name) declared, "I think I feel something in my big toe."

We weren't high; but we weren't sure why. We thought maybe we needed more time to let it kick in, or maybe that dancing under strobe lights might help the situation. So we went to the concert feeling slightly giddier than we might have—but it was hard to tell if the giddiness was the pill, or the idea that we were on it.

That's kind of what using the Cove is like. It says it helps you "conquer stress" and "sleep better." And wearing it, I feel something—I think. But it's a little hard to tell whether it's a Ronald-ian "tingle in my big toe" from bum drugs, or it's actually the stress relief that I've been promised.

That doesn’t mean it’s bad! It’s almost certainly not going to harm you. If you, like me, feel stressed out a lot and are interested in gadgets that might be able to help, it’s a fun thing to try. But I also don’t find myself gravitating toward it too often. Every once in a while I’ll put it on when I’m sitting around the house—but it hasn’t become a regular routine.

My final conclusion is this:

Touch, as a general phenomenon, is incredibly helpful for managing stress. But activating CTAs is only a small part of touch. First, there are other receptors on the skin that are activated during social touch that are probably important to the experience beyond just CTAs. But second, there are a lot of contextual features of a touch experience (like who you’re with, and what the setting is) that are going to matter a lot for whether you experience stress release from it.

It’s pretty appealing to think that there are these magical joysticks on your skin that you can wiggle in a special way and automatically experience a reduction in stress. But even the literature on CTA activation doesn’t really say much about stress. It implies that when you’re sitting in a lab and a scientist moves a device at a certain speed across your arm it feels pleasant—but it doesn’t yet explore how that might affect your stress levels if, for example, there was also a lion or a product manager sitting uncaged in the room with you.

The truth is that your body is filled with different sensors to tell you what’s going on, and if you want to create maximum stress relief and pleasantness you’re probably going to want to stimulate more than just your CTAs.

Experiencing touch, in its entirety, is a little like listening to an entire orchestra play a symphony. There are many different instruments—violins, cellos, flutes—each playing different parts to create a rich and complex experience. On the other hand, just activating CTAs is a little like listening to 30 seconds of a violin solo on HitClips.

It just ain’t quite the same.

So, we still don’t have a switch we can flip to turn stress on and off. But as far as candidates for where we might find one, physical touch might be a good one to bet on—eventually. There is no silver bullet yet, so if you want to experiment with touch, it’s worth trying out all of the options.

Try the Cove. Or try a gravity blanket. Or getting a dog. Or getting a massage.

Or, more simply, just get a hug from someone you love. You’ll feel better, I promise.

I want to thank Cove for sending me a device to try out, and for spending time with me on the phone explaining the science and thinking behind it. It’s difficult and scary to build new things like this, and I’m glad people are trying. It gives me no pleasure to say that it didn’t quite work for me. I’m always willing / interested to review more science or try new versions of devices like this!

I am optimistic about the future of these kinds of devices, and I’ll be reviewing more of them over time. Got one you want me to try? Leave a comment!

If you’re interested in learning more about the science of affective touch I heartily recommend:

Affective Touch and The Neurophysiology of CT Afferents, edited by Olausson, Wessberg, Morrison, and McGlone.

Dr. Olausson was kind enough to read a draft of this piece to make sure I got my science right, and I deeply appreciate that. If you think I’ve gotten something wrong, please hit reply and let me know!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!