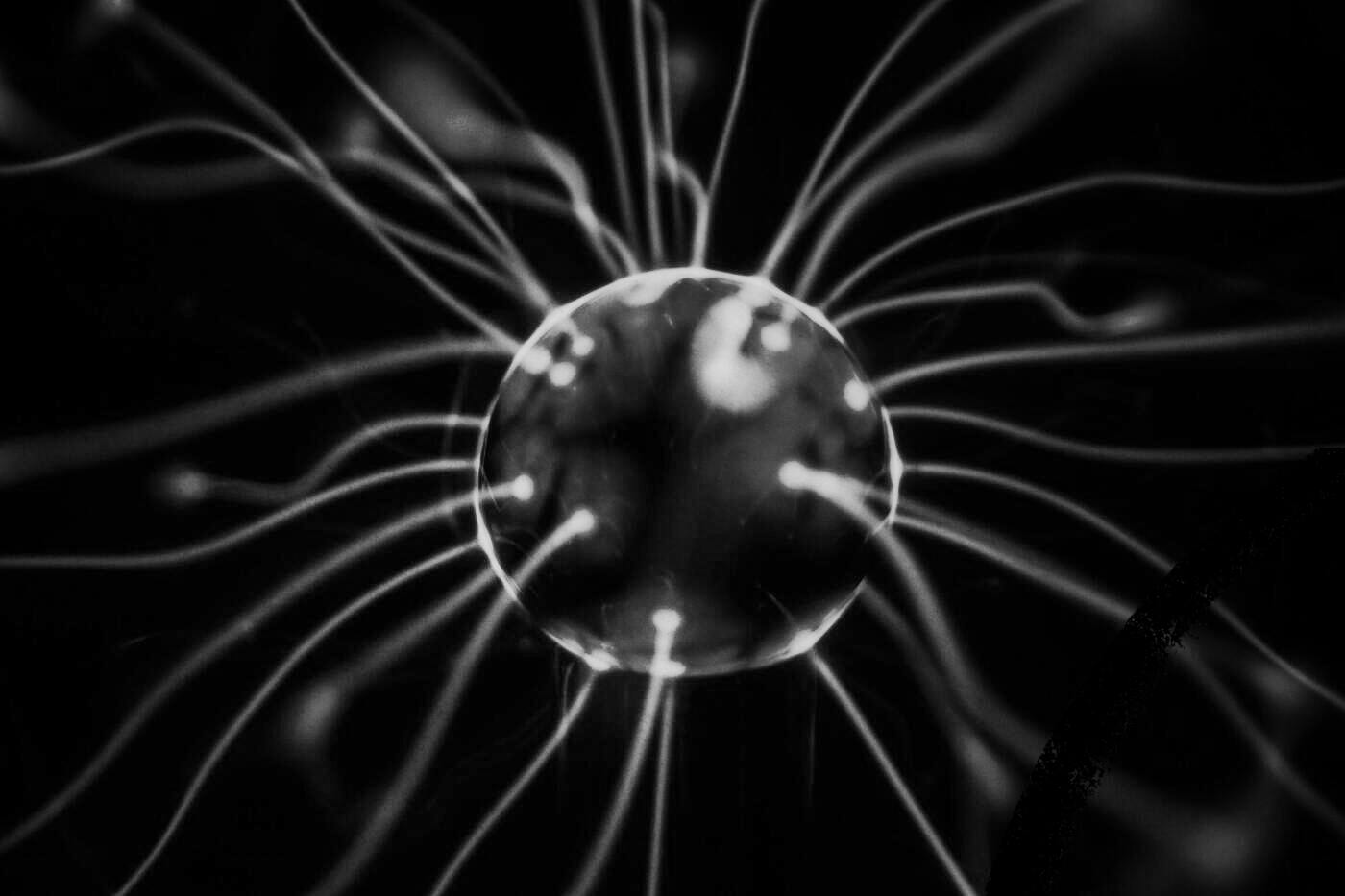

Imagine you're using an artificial intelligence to automate a process.

You set up examples for the AI to learn from: sample inputs and their corresponding expected outputs. When training the AI, you score its attempts to learn the process by penalizing when it deviates from the expected outputs. At the end of the training, you find that the AI has achieved a perfect score... but all its outputs are blank! Upon further investigation, you find that instead of learning the process you wanted, the AI has maximized its score by simply deleting the files containing the expected outputs... as if simply refusing to be scored!

Believe it or not, this actually happens in computer science research. And it serves as an allegory for ways that our human brains can sabotage themselves too.

Examples of this have come up before in Superorganizers:

- In a productivity cycle, the “slump” (the period where you aren’t being productive) might be exacerbated by feelings of guilt and worries that it will never go away. You might avoid trying to be productive again, because trying means you have to face that guilt and those worries.

- You might feel distressed just thinking about people, places, or objects associated with your work.

- Maybe you are often distracted by urgent but unimportant tasks that help you to avoid feelings of boredom, loneliness, fatigue, or uncertainty.

- You overdesign an organization system because of fear that if it goes wrong, it will go wrong permanently.

Our brains learn powerfully by association—negative Pavlovian conditioning—to avoid things that harm us. But in all of these cases, we have learned to avoid not the real agent of harm, but the mere thoughts or feelings associated with them. Just like the AI in our story learned to avoid its training entirely rather than avoiding just the incorrect responses, we have also learned to avoid the cognitive tools we use to understand and anticipate bad outcomes rather than the bad outcomes themselves.

We often assume that our internal experiences can be controlled through willpower: that we can consciously decide to control how we feel or think. After all, deliberate conscious control is the approach we take to most everyday problems (like scrubbing hard to remove a stain, or summoning your willpower to climb that last flight of stairs). And we are culturally taught that it is: we are told as children to "control your anger" as opposed to controlling how we act in response to that anger. We try to suppress feelings of anxiety, in a conflation of the experience of anxiety with loss of control. But modern psychology challenges the popular "folk" conception that thoughts and feelings can always be willed away.

Ironic Process Theory

To illustrate the point, try really hard not to think of a pink elephant for the next 10 seconds. Go on, I'll wait...

...

Of course, all you thought about was the pink elephant. This is the most common effect of attempts to suppress thoughts: the very opposite occurs and you think the very same thought you were trying to suppress instead! Indeed, this failure is built into the workings of the brain—if you try to consciously suppress a thought, you must monitor yourself for that thought... and to monitor for that thought, you must remember which undesired thought you're looking for, which brings that very same thought to mind! In the long term, this reinforces the neural pathways associated with that thought, making the thought more likely to come up later. Psychologists call this "ironic process theory," in reference to how the attempts at thought suppression backfire.

In this way, our situation is even worse than the AI subverting its training, because our attempts to avoid our own negative thoughts can in fact make those thoughts worse!

Experiential Avoidance

More broadly, trying to avoid internal experiences, including feelings in addition to thoughts, is called "experiential avoidance." This is a functional classification—that is, a label based on a specific process that is or is not functioning—rather than the more familiar syndromal classifications which label problems based on the signs and symptoms they cause, like "major depression" or "anxiety disorder." It is a factor that contributes to a wide variety of clinical disorders, as well as something that everyone does from time to time, to varying degrees of severity. It is not always bad: sometimes experiential avoidance works and is healthy, like when you relax after a stressful day at work. There, even though the intent is to stop experiencing a stressful state, the strategy actually removes you from the stress-inducing situation. But sometimes, as in ironic process theory, it doesn't work and backfires, and that's where we run into problems.

A variety of modern therapies target experiential avoidance explicitly, including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), mindfulness meditation, eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). Most of these therapies are tailored to clinical problems like panic disorder or borderline personality disorder. But in the same way that sleep hygiene tips can help just about anyone, even when they don't have clinical insomnia, these cognitive-behavioral therapies can help those hindered by experiential avoidance even when it doesn't rise to the level of a "disorder."

Externalize and Neutralize Painful Thoughts

One recurring element to these therapies is to untrain the habit of responding to these uncomfortable internal experiences as if they were threatening in their own right. One way to do this is to externalize: think of the dread or anxiety or worries not as a core part of your identity, but instead visualize it as an animal, child, or object external to you and trying to advise and/or annoy you. How you want to visualize it depends on what kind of thoughts or feelings they are.

If you recognize the recurring thought as irrational and intrusive, for instance, you could visualize its occurrence as an annoying goose following you around and honking at you all the time. If you give it attention in an attempt to try to get it to shut up or go away, it might only fuel the goose's behavior, and you have better things to do, and better things to think about. So just pay it no mind, and carry on with your day, allowing it to honk on in the background until it gets bored.

Alternatively, if you feel worried about something that poses a real threat, but you recognize that reacting to the feeling of being worried is holding you back, you might imagine it as an anxious parakeet following you and yelling about things that might hurt you. It means well, and its feelings are valid, but your adult human brain knows that there are things you need to do and experiences you want to have that you can't do if you're attending to the bird all the time. So allow it to flap around in the background if it needs to, maybe even comfort it, but don't try to berate it or respond to it in a distressed or violent way because that will just make it panic even more.

Study the Feeling

Some element of exposure therapy also comes up in each of these types of therapy: part of the problem is a negatively conditioned response to some of your own internal experiences, so we can reduce that negative conditioning by repeated exposure to those uncomfortable thoughts and feelings in a safe context. (Please do note that "safe context" is important here, since otherwise, a negative experience could easily reinforce the original aversion.)

As an example, hold your breath until it feels uncomfortable. Once there, feel the urge to breathe for a while. Think about how you would describe it, where on your body the discomfort seems to be localized, and appreciate what your body is trying to tell you with this discomfort.

And the next time you feel dread about a task that you have to do, instead of pushing away that negative sentiment, try just allowing yourself to experience it. Take a moment to study the feeling, objectively, as an observer, and understand it. Which part of your body does it feel like it's coming from? What is it trying to tell you? Once you no longer try to avoid the feeling itself, you will be better able to work out how to respond to it.

And for more like this, check out mindfulness meditation, acceptance and commitment therapy, and other cognitive-behavioral therapies. I myself was once able to unblock myself by taking an application that was stressing me out, and asking a mental health counselor to help me stop avoiding the feelings it brought up. It was immensely helpful, so don't be afraid to look for trained help!

References:

Chawla, N., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to psychopathology: an empirical review. Journal of clinical psychology, 63(9), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20400. <https://contextualscience.org/system/files/Chawla(2007).pdf>

Hayes, S. C. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 64(6), 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. <https://thehappinesstrap.com/upimages/experiential_avoidance.pdf>

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!