In The Future of Ebooks, I laid out a vision for what books could become in a world free of technological constraints. But the modern reality of publishing is decidedly less idealistic.

I’ve spent the past couple months immersed in the world of nonfiction book publishing, trying to deeply understand the state of the industry. I’ve read dozens of articles and books, spoken to experienced agents and editors, and authors ranging from New York Times bestsellers to self-published writers.

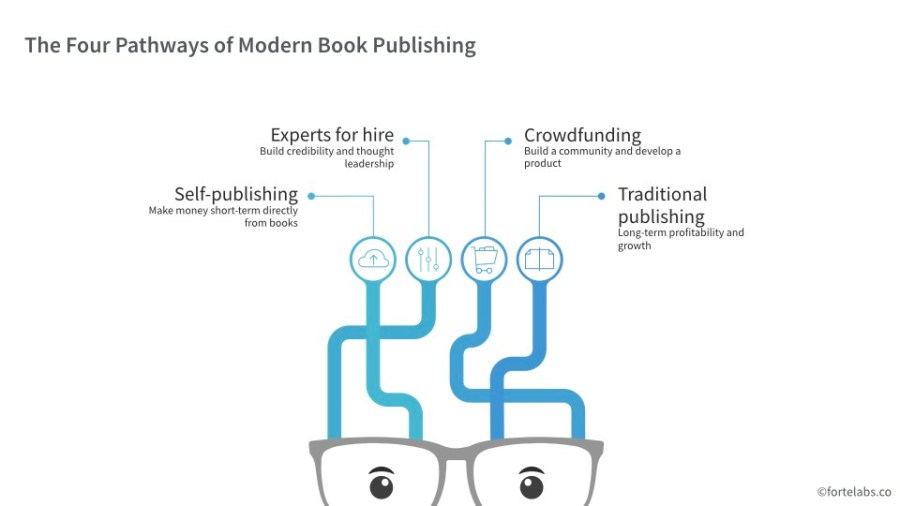

I’ve found that the choice between “traditional publishing” and “self-publishing” is not quite so simple. We are witnessing not just the fall of the former and rise of the latter, but a cornucopia explosion of different publishing options. These pathways intersect and overlap in many places, but I believe that four of them have emerged as the main options, serving distinct purposes and goals:

- Self-publishing: Make money short-term directly from books

- Experts for hire: Build credibility and thought leadership

- Crowdfunding: Build a community and develop a product

- Traditional publishing: Long-term profitability and growth

Let me briefly explain what each of these pathways entails, and then tell you which one I’ve chosen and why.

Self-publishing: Make money short-term directly from books

The rise of self-publishing has been swift, dramatic, and profound, putting a capability once requiring millions of dollars of continuous spending into the hands of anyone with a computer, internet connection, and bank account

The king of the self-publishing world is Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), a self-service web portal that handles everything from manuscript conversion, to configuring book listing pages, to tracking sales, to running promotions. All you have to do is upload a properly formatted Word document, decide on a cover image and listing details, and you can have your ebook on sale around the world within hours.

For this incredible service, KDP charges a dual royalty rate depending on the price you set for your ebook: if priced between $0–9.99, they take 30% of gross revenue; if priced $10 or higher, they take 65%. Which means that if you’re going to charge more than $9.99, you need to charge at least $20 to receive the same royalty payment of $7. I believe that Amazon’s strategy is to undercut the traditional $10-20 price range that most booksellers need to turn a profit, by pushing most of their self-published titles to be less than $10.

The main advantages of self-publishing are:

- Control over contents and appearance (vs. having to compromise with the needs and desires of editors, agents, and publishers)

- Speed to market (available for purchase on Kindle stores around the world within about 24 hours of uploading, vs. 6-18 months for traditional publishing)

- Higher royalty rate (35-70% vs. 10-15% in traditional publishing)

These are significant benefits when compared to the old world of scarce gatekeepers. Anyone can write a bunch of text and publish it as a book, which is a miracle of modern technology.

But I think in our rush to usher in a new world, we’ve somewhat exaggerated the benefits of self-publishing. What good is control if you don’t know what you’re doing? What good is speed to market if no one knows about it? What good is a higher royalty rate if few people buy?

Several years ago I downloaded a free ebook by James Clear in exchange for my email address, called Transform Your Habits. It contained most of his ideas and advice on habit formation and breaking bad habits, and yet self-published on Amazon it would have hardly made a ripple compared to his mega smash hit Atomic Habits. Sure, James benefitted from a few more years of research and writing. But I think the true difference is in the trial by fire he undertook in getting this book ready for a mainstream publisher.

The problem with self-publishing is that the success of the book rests entirely on your shoulders. You are responsible not only for the writing, but for the graphic design, the positioning, the partnerships, the marketing, and the promotion of the product over a long period of time. And the success of your self-published book depends just as much on these other activities as on the content itself.

It is possible to do all these things well (or well enough) and capture nearly all the profits from a breakout success. But the chances of doing so are exceedingly small. I’ve self-published four books over the last few years, and sold maybe a few hundred copies in that time. I’ve learned a lot from walking the self-publishing route a few times, but it’s time for something new.

Experts for hire: Build credibility and thought leadership

One of the greatest benefits for a published author is the boost to their credibility and authority that only “having a book” can provide. Demand for this form of social proof has inspired a vast market of “experts for hire.” These experts unbundle the functions of the traditional publishers and sell them piecemeal:

- Copyediting or ghostwriting

- Strategy and positioning

- Wholesale and retail distribution

- Online and traditional marketing and promotion

The main target of these specialists has been wannabe thought leaders: consultants, coaches, trainers, and other subject matter experts who want a book as a tangible symbol of their expertise. They’re much less concerned with making money directly from book sales, and more concerned with visibility and exposure for their existing work. They want something to put on their website, to hand out at conferences and events, and to send to potential clients. The biggest of these thought leaders even have a chance at making a bestseller list, and there are specialized consultants dedicated to clever and even illicit ways of making that happen.

Experts for hire are often freelancers or micro-agencies who specialize in one slice of the publishing value chain. Sometimes they even come together and “rebundle” the publishing stack, like Page Two Books, which manages the whole project from concept development and market analysis all the way to final printing and distribution, for $20,000–30,000. This all-inclusive offering can be very attractive to established experts who want to write a book without having to manage all the tiny details of the project.

There’s even an option for those who want a book without doing the writing themselves: ghostwriters. Once seen as shadowy figures who were expected to remain at least semi-anonymous, ghostwriters have now become a reputable profession like any other. Scribe Writing (formerly known as Book-in-a-Box and founded by successful self-published author Tucker Max) offers two packages at $36k and $100k that include a comprehensive process for interviewing an expert, recording and structuring their ideas, and writing the book based on that material.

This pathway obviously requires quite a bit of upfront investment. But for those willing to foot the bill, the “experts for hire” pathway provides a middle ground between the complete self-reliance of self-publishing, and the full-fledged traditional publishing route. It allows people with some money to spend to acquire just the expertise they need, capturing the low-hanging fruits of credibility that only a book can provide.

Although I might be willing to hire such experts, there is one thing they can’t offer me: mainstream exposure. They can offer their wisdom and advice, but ultimately I am the client and what I say goes. Although that is appealing from a creative control perspective, it also means I will continue to do things how I’ve always done them. If I really want to break out of my tiny niche of philosophical productivity geeks, I will need more than service providers. I need someone with skin in the game.

Crowdfunding: Build a community and develop a product

This one is a bit of an outlier, incorporating elements from the other three pathways. You get the total control of self-publishing, plus some of the funding that allows you to hire the experts you need, plus some of the validation that comes from traditional publishing (in the form of pre-orders).

Crowdfunding is basically a more structured and time-compressed way of building the popular groundswell that you would otherwise use a blog to create. Instead of a very slow, patient effort to build an audience over a long period of time, you supercharge the process with slick online marketing campaigns, urgent deadlines, impressive-sounding funding milestones, and prizes.

While attractive for many reasons – you get paid before the book is created and launch it to a waiting audience – it’s become clear in recent years that successful crowdfunding is really hard. The largest campaigns require a level of sustained effort comparable to starting a company, while even smaller campaigns for individual authors require a tremendous amount of work. Creating webpages and media kits, promoting and pushing the campaign, and of course, keeping track of and sending out numerous tiers of “perks” isn’t easy, and exist apart from the actual writing of the book. Experts can be hired to manage this process, but they aren’t cheap.

Crowdfunding is a viable pathway for those that have a longer term goal: to build a community around the book. While the campaign itself is unlikely to be very profitable with all the work required to run it, the long-term relationship with the community can make it worth it. This is why crowdfunding campaigns often lead to developing a “product line” of follow-up books (and related products) for the same audience, such as Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls 2.

The crowdfunding route has a lot of benefits, but I think I’m already past the stage where it makes the most sense. I already have a strong, loyal following that I know will be ready to buy on day one. And I already have a full-length manuscript of the book. I could stage a “bookwriting process” and pretend that I was using crowdfunds to develop the book, but that wouldn’t be genuine and would involve a lot of extraneous work I’m not willing to do.

Traditional publishing: Long-term profitability and growth

The paradox of modern publishing is that, the more traditional publishing shrinks, the more prestigious and coveted its blessing. The world of constantly self-promoting internet thought leaders has exploded so fast, that the imprint of a traditional publisher is more than ever a symbol of quality

Strangely, this makes the slowness and bureaucracy of these venerable institutions into competitive advantages: it is assumed that any book that makes it through so many rubber stamps and gatekeepers must be credible.

And in a way, this is true. Publishers may no longer be the gatekeepers for getting published at all. But they are still very much the gatekeepers of what makes it into the mainstream. Most people and institutions alike still make the decision about whether to buy and read a book not based on its merits, but on social proof. Traditional publishers are still the tastemakers that signal whether a book has been vetted.

Everything about the way they work is targeted toward a mainstream audience of book readers: the editing process seeks to make the language as accessible as possible; agents work to craft a proposal that aims for the largest share of the reading public; publishers buy books that tap into up-and-coming trends and movements. Their main capability is making bets on ideas that are just about ready to break out of a niche into the broader culture.

Most of the criticism of traditional publishing has centered around its unprofitability. And it is indeed unprofitable in the short term. From Tim Ferriss’ Definitive Resource List and How-To Guide to Book Publishing:

- Advances are small and declining: less than 6% of all reported deals get an advance of more than $100k (as of 2011, and it’s gone down since)

- Few books sell many copies: on average, fewer than 100 Hardcover Nonfiction Bestsellers in any year sell more than 100,000 copies, and usually only one or two top 1 million sold.

- Even for what does sell, the author doesn’t make much: for a hardcover book, authors typically receive a 10-15% royalty on cover price; for a trade paperback book, authors typically receive around half the royalty of a hard cover (7%)

- And there are other expenses: literary agents take between 10-20% of domestic, subsidiary, and foreign sales; some costs such as outside editors or online marketing consultants may be borne by the author

- Nonfiction books have an even tougher time: nonfiction books that deal with advice, how-to, political and a host of other prescriptive and practical matters (including some religion) are treated by the New York Times separately from all other non-fiction. They are given the shortest of all the lists, the 10-slot weekly “Advice/How-To” list, sometimes referred to as the “Mt. Everest of lists.” To make matters more confusing, the Times refuses to track eBook sales for all this “lesser” non-fiction

And it’s not that publishers are intentionally screwing over authors, either. Anecdotally, publishers actually lose money on about 80% of book advances. That is, the book never sells enough to cover even the cost of the advance. The publishing industry closely resembles the venture capital industry in this way: the profitable 20% has to cover their expenses for the losing 80%, plus hopefully turn a profit.

This is why traditional publishers aim so squarely for mainstream hits: their entire business model depends on “unicorns.” They are looking for the massive successes that create a long-term flow of consistent income far into the future. And they have a ruthless eye for this, looking most closely at:

- The stats and analytics behind your online following, including all websites, blogs, social media accounts, e-mail newsletters, regular online writing gigs, podcasts, videos, etc.

- Your offline following—speaking engagements, events, classes/teaching, city/regional presence, professional organization leadership roles and memberships, etc.

- Your presence in traditional media (regular gigs, features, any coverage you’ve received, etc.)

- Your network strength—reach to influencers or thought leaders, a prominent position at a major organization or business

- Sales of past books or self-published works

The thing is, mainstream success is just about the least sure thing that exists. It obviously depends on hundreds of other factors outside their control, and your control, and anyone’s control. It’s not a clear-cut financial return, like “70% royalty rate.” By working with a publisher, you are leaving a lot of value on the table to keep open just the slightest possibility of mainstream success.

But this isn’t as black-and-white a proposition as it seems. Both the proposal and the manuscript go through a process of simplification and distillation as editors and agents make the idea palatable to the decision makers at major publishers. That simplification process is inherently valuable even if it’s not a viral hit, and even if no publisher buys the book! The long-term success (and therefore profitability) of the BASB franchise depends on being able to make an impact outside my early adopter audience, and I see the traditional publishing route as a forcing function to make that happen.

I believe that this process – of translating my ideas into the language of a mainstream audience – is the most important thing I need. I’ve developed Building a Second Brain as an online course for a very nerdy, technical, engineering-centric audience. This has been perfect, giving me a solid foundation of logical, precise thinking under my feet. But at the same time, this has made some of my explanations almost indecipherable to outsiders.

It’s time to bring my ideas about digital note-taking, personal knowledge management, and “second brains” out of the tiny niche of early adopters, and into the mainstream of society. For that reason, I’ve chosen to take the most conservative, most traditional publishing route.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!