Editor’s preface: The future of work is uncertain as we move into a post-Covid world. We’re seeing the rise of new marketplaces for job placement, tailored to the unique needs of disparate industries. In this article, Every OG Adam Keesling explores the implications of this shift.

A vertical labor marketplace is an online platform that matches workers and employers. It’s not so different from “horizontal” labor marketplaces like Upwork or Fiverr, except that vertical labor marketplaces are built with unique features for particular industries. The way hospitals hire surgeons is very different from how local restaurant chains hire servers, which is also very different from how high-growth startups hire technology executives.

Traditionally, labor marketplaces solve “the matching problem.” Employers need tasks completed, and employees know how to do those tasks. So, match them. Vertical labor marketplaces will do this, but they will do more than just match employees. Expect these new marketplaces to also help employers track their candidates through the recruitment funnel, immediately issue credit cards to new employees that are only accepted at pre-approved vendors, process payroll in the same software system, and much more.

Vertical labor marketplaces will be one of the most compelling venture and growth equity investments over the next decade. If a vertical labor marketplace can solve a problem and make it past the initial phase of finding product-market fit, they develop into businesses with attractive characteristics. They typically have a clear path for growth, strong two-sided network effects, and natural operating leverage from building a technology platform. All things that make them incredible businesses to own.

But it’s not just investors that should pay attention to vertical labor marketplaces. Most people reading this will be participating in the labor market in one form or another. How should the proliferation of these digital labor marketplaces impact your career strategy? What is exciting about them as a participant, and what’s a bit scary about them?

In this post, I dive into the economical and technological trends that make vertical labor marketplaces exciting right now. Then, I do a deep dive into three vertical labor marketplaces that I think are particularly interesting (for investors, operators, and labor participants alike).

Let’s get into it.

Why vertical labor marketplaces are interesting right now

1. Workers are leaving jobs at historically high rates.

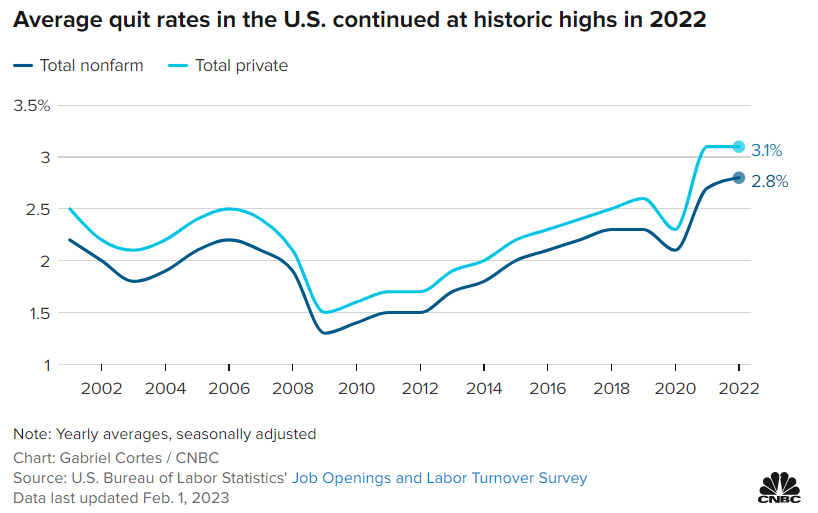

While labor was dramatically impacted by the pandemic, as we move into 2023 we are starting to see signs of what the new status quo will look like in the labor market. One thing has been clear: workers are leaving jobs at historically high rates. The “Great Resignation” was coined in 2021 after a record number of workers quit their job, but was surpassed in 2022 after another record-breaking number of people left jobs. This is a historically high number in both absolute resignations (50.5 million) in addition to average quit rates (3.1%).

SourceInterestingly, workers are often leaving to start at another job rather than leave the workforce entirely. Employers hired a record 76.4 million people in 2022, compared to only 16.8 million people laid off.

While some workers are leaving voluntarily, others are not. The difference tends to come down to industry dynamics. Zooming in on the technology sector, there are between 6 million and 9 million total workers depending on how you slice the data. In the past year the headlines have focused on layoffs as the industry experiences a pullback both in public equity valuations and venture capital funding. Around 93k tech workers were laid off in 2022 with an additional 130k losing their jobs just in the first quarter of 2023 (source). However the rest of the economy is booming with almost 1.1 million jobs added in this same first quarter.

2. Hybrid is becoming the steady state for knowledge workers.

Anyone reading this likely knows the knowledge worker Covid story: in 2020, almost every employer implemented a work-from-home policy. In 2021, companies started returning to their offices, and since then, they’ve been trying to figure out the optimal working policy. Employers are forced to balance employee productivity and happiness with things like competition for talent and different kinds of expenses (trading rent expense for off-site costs).

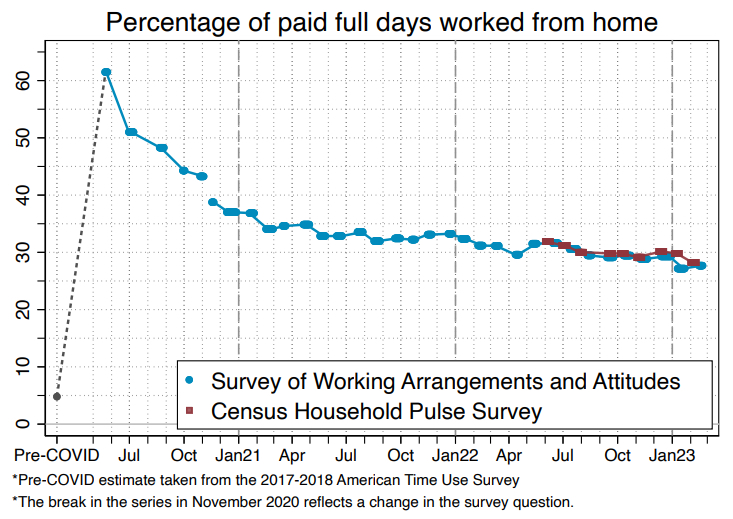

During the pandemic, workers were spending over 60% of their paid days working from home. Since then it’s been plateauing around 25-30%.

SourceThere are a few results from these trends. Local jobs have become national jobs, and national jobs have become international jobs. Increasingly, employers are willing to hire people outside of their local market. While some companies are explicit about outsourcing, others perform “pseudo layoffs” by forcing workers to come into the office. The idea is this: if you force workers to come back to the office, inevitably some of them won’t want to and will quit on their own will. Companies can hire cheaper labor overseas without having to lose face by laying off expensive US-based workers.

3. There are still vast labor shortages in many industries, and training is only one part of the problem.

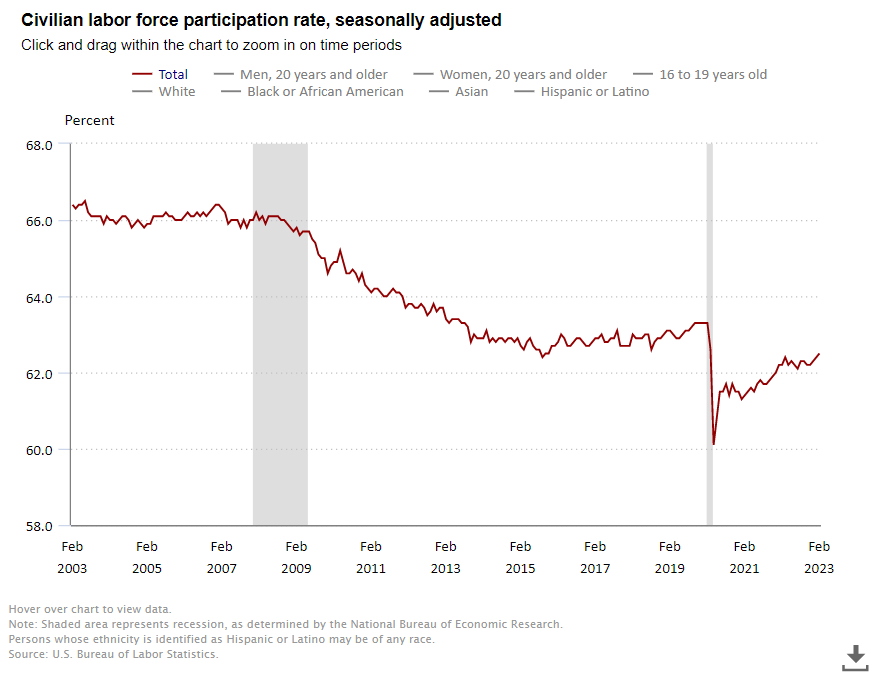

While many of the workers who resigned in the past few years found new jobs, a healthy minority left the workforce altogether. The labor participation rate is the lowest it’s been in 20 years.

SourceA lower labor participation rate has accelerated shortages in a number of industries. Just a few examples:

- Nursing. There are about 2.99 million nurses in the US (source), and depending on your source, in order to keep up with demand there would need to be about 50k new nurses added per year. Unfortunately, factors are stacked against meeting the demand. Around 100k nurses left the field after 2020 (often citing understaffing as a motive), the average age of a nurse is 52 (higher than the ~40 average age of an American worker), and nursing schools also face such a labor shortage that they’ve had to decline over 91k qualified applicants due to lack of staff.

- Agriculture. 10.9% of total US employment (22.2 million jobs) are related to the agriculture and food sectors, and yet for every two agriculture jobs there is one applicant. The amount of jobs in agriculture continues to grow and so does the labor shortage.

- Skilled Trades. Each year, 10k electricians retire and only 7k join the industry (source). A 2020 report predicted a shortage of 642k auto/diesel/collision technicians by 2024. Another 2022 study forecasted a shortage of 557k plumbers by 2027. Across the skilled trades, there’s a labor shortage driven largely by a generational shift away from the work.

One would think that during a labor shortage, training new workers would be the main issue, but oftentimes it’s a lot more nuanced than that. For example, in nursing, there’s also a shortage of demand for nursing school and a shortage of nursing school staff. The whole industry needs help. This is the case in many industries where training might be a problem but there are other problems that also need to be addressed.

Besides the macroeconomic labor shifts, new technological advances make it a relevant time to build a labor marketplace.

Embedded finance dramatically expands the revenue potential

One of the most exciting trends for growth-stage vertical labor marketplace businesses is the rise of embedded finance infrastructure. Embedded finance is the use of financial tools or services by a non-financial company; an example might be a consumer electronics shop offering personal insurance on a laptop at the point-of-sale.

In some ways, embedded finance is nothing new. For anyone who still watches TV, you’ll see Ford 0% financing commercials in between your programming. Ford offers its customers a banking product (lending) despite principally being in the business of selling cars and trucks. Other familiar examples include appliance financing and airline credit cards.

In other ways, embedded finance is something new. These days there are many more examples of non-financial companies offering financial products in digital interfaces. The best opportunity is when the user (a business or consumer) uses a digital product daily; this often creates the possibility to insert a financial product into the workflow.

Embedded finance makes it a lot easier for vertical labor marketplaces (and vertical software companies in general) to solve problems: initial wedge products are easier to build, and add-on products enable a single company to serve multiple needs. Instead of just a pure “matching” platform between workers and employers, you can imagine applicant tracking systems, benefits administration, compliance, payroll, payments, and other services that startups can now easily build.

Embedded finance products also enable vertical labor marketplaces to offer additional products (and thus grow into bigger companies themselves). For example, a labor marketplace might help a commercial HVAC servicing company hire technicians (and collect a fee for doing so). But they could also help the employer pay the technicians (payroll, payments) or easily issue credit cards (that are only accepted at pre-approved vendors) to the technician to pay for materials (issuing) without having to get approval from their manager. All of this could be done from the same software interface with all the data in one place.

The market size for embedded finance is already estimated at $20 billion, and (according to McKinsey) it’s expected to double over the next few years. Vertical labor marketplaces will work hand-in-hand with embedded finance companies to offer financial products to workers and employers.

Vertical labor marketplace examples

These types of companies are exciting for the reasons I’ve already talked about, but it clicked for me when I learned about specific use cases. Here are a few industries and startups I’m particularly excited about from an investor’s perspective.

Seso Labor (Agriculture)

For every two farm or farm-related jobs posted in the US, there is one applicant. It’s estimated that labor shortages contribute to $3.1B in rotted crops each year. While there are many problems that farmers face each day, labor is one of the largest.

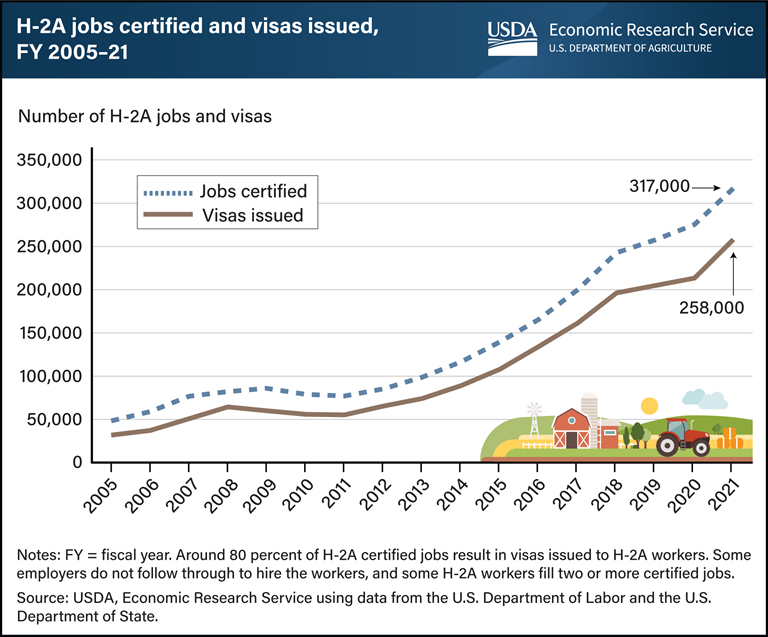

Perhaps my favorite company on this list, Seso is an agriculture technology company that provides labor software to farmers. Specifically, Seso helps farmers and workers with the H-2A visa application process. The H-2A visa is a visa that allows immigrants a temporary (up to 10 months) visa to work on a farm seasonally. The reason the visa exists is to allow farmers to legally employee immigrants when there aren’t enough US citizens to work agriculture jobs. It helps solve the shortage of American workers.

The H-2A visa has increased in popularity over the past several years. In 2005, there were fewer than 50,000 H-2A visas issued. In 2021 there were 317,000 H-2A visas issued.

Despite the popularity of the H-2A visa, there are many problems with the application process from both the employer and employee perspective.

In order to utilize the H-2A visa, employers must prove (and the Department of Labor must approve) that the employer tried and failed to recruit US workers. This requirement is to protect American workers — without the proof, farmers might be incentivized to hire immigrant workers for cheaper wages, thus crowding out American workers. The process is tremendously tedious. It has over 200 steps, takes 75 days and requires approval from three separate government bodies (source).

The workers also have problems. While salaries from the H-2A visa are often 10x what most workers would earn in their home country, the process hasn’t been easy to get these US agriculture jobs. Often predatory “labor contractors” will “help” workers (primarily from Mexico, which accounts for the vast majority of people using the H-2A visa) by connecting them with American farms but forcing them to pay a fee in the process. This leaves workers with debt going into the job.

Seso solves these problems by making it easier and cheaper for employers (up to 24% cheaper) to hire workers with the H-2A visa. It also makes it smoother for the worker: Seso provides a better solution than the labor contractors and doesn’t charge workers for the service.

Seso is founded by Michael Guirguis (CEO) and Jordan Taylor (Head of Product). The co-founders have relevant and complimentary backgrounds: Michael previously led operations for Yup.com (a tutoring service) and Jordan previously was Director of Product at Farmers Business Network (a high-growth eCommerce platform serving the agriculture industry). Seso has raised a total of $29.5 million and is backed by Index Ventures, Founders Fund, NFX and others.

Vivian (Nursing & Healthcare)

Formerly called NurseFly, Vivian is a labor marketplace focused on healthcare workers. The issues in the nursing labor marketplace are nearly endless: understaffing, a retiring workforce, and low nursing school enrollment all continue to industry-wide stress. But Vivian has been solving the problem through their marketplace. Workers can search and find jobs. Employers can post jobs, chat with candidates and view important information like past experience and certifications.

Vivian has flown under the radar relative to their success. In my opinion it’s because their capital structure hasn’t followed the typical venture path (aka they haven’t had a VC to sing their praises on the internet): they were founded in 2017 and sold to IAC for $15 million two years later. It wasn’t until April 2022 that they had another financing event, raising $60 million from Thoma Bravo.

The scale of the business is tremendous. From public information, it looks like they are still growing around 3x year-over-year off of a pretty large base.

I have no information about their revenue model, but even a 10% take rate would mean $150 million in revenue in 2022.

While Vivian started with travel nurses, their vision is to onboard each of the 18 million healthcare workers in the US and become the definitive “LinkedIn for healthcare”. If I had a growth equity fund, Vivian would’ve been at the very top of my investing wishlist. They check all the boxes: high growth, sticky platform, mission-critical for customers, marketplace dynamic with network effects, large market, high reinvestment runway (including growth through acquisitions), and a strong team. Expect to see an S-1 from Vivian in the next couple of years.

Workrise

Founded as RigUp in 2014, you can think of Workrise in the same vein as Vivian: a digital labor marketplace focused on a specific industry (in the case of Workrise, energy). Think of the benefits for each side of the marketplace. For energy companies, Workrise provides the same basic benefit as a labor contractor (a set number of workers for a project) but has additional benefits through the tech they provide. One customer noted a few of the most impactful things Workrise did: managing background checks, coordinating safety equipment and training, handling paperwork, managing workers’ hours and being responsive.

On the worker side, Workrise allows them to accumulate an online reputation through a profile that shows various credentials and past projects that they’ve worked on. A better user experience both through the online portal and (seemingly) strong customer service makes Workrise a preferred choice over legacy labor contractors.

Zooming out, the dynamics of the industry make it even more likely that an online labor marketplace like Workrise exists. Projects across the energy sector, from oil & gas to renewables, typically have a large upfront build / install expenditure followed by a maintenance period. The peak demand for labor, then, happens during the build / install phase (typically a few months at a time). Then, workers move onto the next project. This creates a natural opportunity for a platform to facilitate these frequent job changes and connect worker reputations over time.

Workrise is no small company. Workrise’s “gross revenue” grew from $300 million in 2018 to $900 million in 2020. However, it also hasn’t been without ups and downs. In 2020, they laid off a quarter of their workforce (citing industry slowdown due to Covid). They then raised more money and pushed into new verticals outside of energy. Then, more layoffs (up to 450) in 2022 as the company refocused back to energy (oil & gas and renewables).

Where does the company go from here? Workrise has a lot of room for growth. They have 5,000 workers on their platform out of an estimated 113,000 total oil & gas workers (not counting everything in renewables). Additionally, it’s not unreasonable to assume they could expand through acquisition. Oil & gas staffing is a fragmented industry with hundreds of small staffing agencies. To further grow on the employer side, it would make a lot of sense to buy those agencies (likely at a low multiple) and plug the demand into the Workrise platform.

(This acquisition through growth strategy, by the way, should be a common growth path for any labor marketplace that starts to achieve scale. Most existing staffing agency markets are similarly fragmented. It’s pretty straightforward to start a staffing business and so there are a lot of them. It can make more economic sense to just buy the existing contracts rather than trying to fight them in a sales or request for proposal (RFP) process.)

The path to liquidity is less clear for Workrise. Without further information on how gross transaction value turns into gross revenue turns into revenue turns into cash flow, it’s tough to get a gut check on the valuation. Two rounds of layoffs (and the CEO shifting to Chairman) likely means a few of the strategic bets didn’t pay off. That said, while layoffs are a bummer for employees, it can sometimes be the right move for the company.

Public companies to early-stage startups

I highlighted a few startups that are executing the vertical labor marketplace playbook. However, these represent a very small sample of what’s possible at the intersection of labor and technology. I barely talked about the knowledge worker class (which includes a number of promising startups), two prominent public digital labor marketplaces ($UPWK and $FVRR), and recent M&A activity (Karat acquired TripleByte just last month). Not to mention past generation successes in labor like LinkedIn.

I also didn’t mention the slew of early-stage startups tackling labor in a wide variety of verticals. There’s Greenwork (clean energy), Classet (construction), Seafair (shipping) and many, many more that have interesting takes on labor in their respective industries. While there are far too many for me to list here, Weekend Fund pulled together a much more comprehensive list of them here that you can check out.

What about you?

So how should you as a labor market participant, perhaps in the technology sector, think about the impact of labor marketplaces? There’s no doubt that more and more candidates will be hired through these platforms.

If you use a labor marketplace, use it early and often. If you decide to try out a labor marketplace for either freelance or full time work, join one that is early and be very active on it. There are two points here. First, use it early. This advice applies to more than just labor marketplaces, but if there’s a novel idea with a lot of traction, oftentimes the company will do a lot for its early users (for example, giving you discounts or giving you priority in a matching algorithm). They want to reward early users. Second, use it often. Even in a mature labor marketplace, there’s almost always a reputation mechanism. If you switch platforms, you lose the reputation and the benefits associated with it.

LinkedIn isn’t going anywhere (for better or worse). As discussed above, one of the best business characteristics of labor marketplaces is their network effects. LinkedIn has network effects as users benefit as more users are added to the platform. It’s not going anywhere. There are some sectors that don’t care about LinkedIn (and they likely never will) but the ones that do will continue to use it as a directory.

Specialization will make you stand out. The internet supports a barbell distribution for a lot of things, including workers. The barbell distribution is this: on one end, the big brands will win as they compete on cost, convenience and brand (think Amazon for consumer goods). On the other end, specialized niche providers will serve smaller pockets of demand. In these cases, the best strategy is to pick a niche and be the best in it. Since you as an individual will occupy the labor market, becoming a large brand isn’t an option. Instead, specialize. Don’t be a great software engineer; be the best Ruby on Rails software engineer who specializes in media websites.

While the future of work may or may not be different, how we find our jobs and who succeeds in the new marketplace certainly will be.

Adam Keesling currently helps funds and independent sponsors with diligence and financial modeling. If you want to discuss any of the ideas in his article, feel free to reach out to him on Twitter or email at adam [at] adamkeesling [dot] com.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I also looked into starting a vertical labor marketplace to solve the skilled labor shortage problem in clean energy trades. Part of that process included digging into Workrise and finding many examples of poor execution: https://buildinclimate.substack.com/p/addressing-the-skilled-labor-shortage