To embrace e-books is to embrace change, to accept that books are collections of words and ideas, to believe that the form factor of a book is not sacred.

For a book is “a written or printed work consisting of pages glued or sewn together,” according to the New Oxford American Dictionary. An e-book, meanwhile, is merely a collection of words in a file, a book only if you squint. It is words, one after another, with no permanence, no sense of length or depth aside from a scrollbar or reading percentage. It is impermanent, flexible, a reading jack-of-all-trades, the farthest thing possible from sewn pages.

E-books, if anything, have more in common with their earlier cousin, the scroll. As Tim Urban discovered when trying to find the optimal way to read his What’s Our Problem eBook, “The best e-book experience … is Apple Books > iPad > sepia > vertical scroll.” Nothing could be closer to a reincarnated scroll—perhaps a more fitting metaphor for electronic texts than the book.

E-books have always felt like they’re missing something. They’re lacking what Glenn Fleishman coined as “bookiness”: “The essence that makes someone feel like they’re using a book.” Bookiness is the heft, the aroma of paper and ink, the sensation of flipping through pages.

The harder e-books try to imitate a book—Apple Books’ paper-like page turn animations, Kindle’s estimated page numbers, and PDF documents’ faithful-to-print page layouts—the worse they feel. No amount of skeuomorphic animations and layout can make up for the slightly off-kilter feeling in e-books when the typography and margins are a bit off and page numbers change on a whim.

We made e-books in the image of books, and in a head-to-head competition on bookiness, the e-book will always come up short. “E-books are digital, but beyond that they’re not much different than books,” remarked tech analyst Ben Thompson in 2015, and maybe that’s been their problem all along.

What if we had it wrong? What if ideas weren’t meant to be bound between covers, locked away in inky, typeset pages? What if the book was only one stage in the evolution of knowledge storage, and now it’s time to reinvent the long-form text?

What if we start over, and remake the book in the image of technology?

From clay tablets to the tabula: tracing the evolution of books

If you step back in time, the book itself wasn’t invented in a single burst of inspiration. The history of books started, as so much of human history did, in Mesopotamia.

Paper had yet to be invented when humans began writing knowledge down to store it somewhere safe to forget. From Mesopotamia on, as early as 4000 BCE, our ancestors scratched their earliest ideas onto clay tablets.

“Tablets were for disposable text,” noted author Lev Grossman. You’d jot down ideas then pat the clay smooth to reuse it later. Monumental ideas could be preserved for posterity, if you wanted, by baking the clay to freeze ideas into stone. Everything else, you’d smooth out and start again tomorrow.

Then someone got the idea to put two clay tablets together to build the first book: the tabula.

Take two pieces of wood, hinged together with a clasp, and cover them with “blackened wax that could be inscribed with a bronze or iron stylus, one end of which was flat so the wax could be smoothed and written upon again,” relays James Grout in Encyclopaedia Romana, and you had a proto-notebook. You’d write and rewrite your ideas and calculations, before smoothing them into oblivion to start over again. It was an iterative update to clay tablets, enough to carry humans and their mobile writing needs into the Roman era.

The tabula was humanity’s first book, crafted in the image of the clay tablet.

Papyrus, parchment, paper, and low-end disruption

Humans innovate, as they’re wont to do, and the state-of-the-art in writing technology started moving on. By the time the tabula was invented (during the dawn of the Roman empire), there was another writing medium for the long-term storage of important ideas: Egyptian papyrus. Made from sheets of Nile reed pith, papyrus emerged around 2000 BCE. It “keeps a faithful witness of human deeds; it speaks of the past, and is the enemy of oblivion,” enthused Roman scholar Cassidorus. It wasn’t for everyday musings. It was for posterity, with lengthy texts rolled into scrolls.

Either a papyrus shortage or an export ban from Alexandria (of Library fame) prompted a switch starting around 200 BCE from papyrus to sheepskin parchment as a drop-in replacement for papyrus. It was a medium change, the iPhone-losing-the-home-button of ancient times. You still wrote the most important ideas and rolled them in scrolls, but now they were made of cheaper, more widely available sheepskin turned into parchment.

That medium change planted the seed for something new. Parchment was cheaper than imported papyrus. That marginal difference meant you could experiment with parchment and find new use cases for it beyond scrolls.

The book was one such use case. Someone in Rome got the bright idea to swap the wood and wax of the tabula with parchment, and invented the first actual notebook—at first, called a codex. A codex could contain as many pages as you wanted, now that you were no longer limited by weighty clay. “Stitched together and protected by a cover, the parchment notebook was used for accounts, notes, drafts, and letters,” writes Grout. This was for ordinary writing, the writing formerly done on clay tablets, not the lofty ideas reserved for scrolls.

The codex was an early example of what Clayton Christensen would call low-end disruption. Parchment was a “good-enough product”—cheaper and more widely available than papyrus, even if it didn’t afford as nice of a writing experience. Parchment changed the medium behind scrolls, then changed clay tabula into early books, before going up-market and changing publishing forever.

If humanity had only shifted the writing material from papyrus to parchment, the medium change would have merely lowered the price of the written word. It was the format shift—combining the innovations of the tabula with parchment into an early book—that changed everything.

The size made information portable, the cover added durability, the pages made information more available, and the parchment brought the price down. It was a virtuous cycle of innovation that brought us the first books.

Then came modern paper made from ordinary bark and wood, invented in China around the year 100 and imported to Europe through the Middle East, lowering the price of the writing medium again. Then came movable type and the printing press to produce full pages of text mechanically, automating the scribe’s job of handwriting books away and easing distribution. Standards grew out of necessity and artistry, with the dimensions of books being based on the original size of folded sheepskin parchment and the typography and margins slowly converging into the one true idea of what a book should be.

Even as books grew in popularity, they didn’t replace scrolls entirely. “Scrolls were the prestige format, used for important works only: sacred texts, legal documents, history, literature,” noted Grossman. Parchment retained that status well into modern times—when 13 British colonies chose revolution, they leaned on parchment’s permanence and authoritativeness to declare themselves the United States.

“New technology seldom eliminates old technology,” wrote Mark Kurlansky in his history of paper. “It only creates another alternative.”

It was the upstarts—the poets, the writers, the dreamers, those whom Steve Jobs would later fondly call “the crazy ones”—who embraced change and made the book take hold. “You, who wish my poems should be everywhere with you … buy these which the parchment confines in small pages. This copy of me [sic] one hand can grasp,” advertised Roman poet Marcus Valerius Martialis (better known as Martial) of his notebook-sized works.

The earliest Christian church also made the book its own, from around 70 CE, with its literature written in books, not scrolls. “The codex permitted longer texts, such as the Gospels, to be contained within a single volume and to be referred to more easily,” notes Grout in his history of the book neé codex. It likely didn’t hurt that books lent the Church the cachet of the new and innovative, moving beyond the stuffy scrolls favored by Greek and Hebrew temples alike.

The book wasn’t invented in a stroke or popularized overnight. It was distilled from clay tablets to hardcover tomes over centuries, promoted by the early adopters and improved by innovators. One page at a time, they made the book the primary information store for humanity, and over the two ensuing millennia, the book became a default. We write quick notes in notebooks, publish more disposable, fleeting ideas in newspapers and pamphlets (both codices by Roman standards, if not books by modern ones), and publish our most important ideas in books for preservation. Over 51 million books fill the Library of Congress today, the greatest store of humanity’s collective knowledge.

It’s hard to think that the book didn’t exist all along.

E-book inventors dreamed of ideas liberated from pages

Then the industrial age shifted into the information age, and doubt started to creep in. What if the book wasn’t the end-all of information storage? The earliest computers made humanity realize books might not be the final resting place for information after all.

“The Encyclopædia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox,” imagined Vannevar Bush in 1947. He contemplated how everyday life could be changed by the computers that helped win World War II—the British codebreaking Colossus computer and IBM’s punch-card accounting machines that aided the Manhattan Project.

“A special button transfers him immediately to the first page of the index,” Bush wrote, imagining an operator navigating a digital book’s mechanical interface. “Any given book of his library can thus be called up and consulted with far greater facility than if it were taken from a shelf.” Nearly five centuries after Gutenberg’s first printing press, Bush was dreaming up the e-book, and search was what would make his matchbox-book better.

A year later, Jesuit priest Roberto Busa decided to take up the challenge, digitalizing the works of 13th-century priest Thomas Aquinas, in what became the world’s first e-book. Seventy people labored over three decades to transcribe 10 million words into punch cards (the earliest way to store computer data, on holes punched into paper cards) and 1,500 kilometers of magnetic tape (the computing equivalent of cassette tapes, storing data magnetically at a far higher density than punch cards afforded).

A matchbox this was not (at first anyhow), until the march of progress reduced the volume to a couple CDs in the ’90s, then a single website powered by a 1.4GB database in 2005. But Busa’s goal was the same as Bush’s: to aid discovery, to unlock the ideas that previously had been bound between covers—not to simply read a book on a computer.

Busa sought to index the works of Aquinas, to find every instance of any specific word or phrase throughout the volumes. For that, a digitized book seemed the perfect disruption—not better than a book, but a companion to a book, a way to analyze its words, if not to read them in their entirety.

Busa and Bush were not alone in trying to rethink information storage. Psychologist J. C. R. Licklider was thinking along the same lines in 1965 as he dreamed of libraries of the future. “Books are bulky and heavy. They contain much more information than the reader can apprehend at any given moment, and the excess often hides the part he wants to see,” he wrote. “Except for use in consecutive reading—which is not the modal application in the domain of our study—books are not very good display devices.”

When these thinkers imagined a digital book—what we’d come to call an e-book—they dreamed of ideas liberated from pages. The book had perfected “consecutive reading,” the long read, the text in which you’d lose yourself. Yet that lengthiness and narrative didn’t aid in information storage, organization, and retrieval, something for which the then-new computers seemed ideally suited.

Along came Michael Hart, the founder of Project Gutenberg, perhaps the singularly most influential project in making e-books mainstream. Hart was gifted free university computing time in 1971, and decided to use that to digitalize the world’s libraries. “The greatest value created by computers would not be computing,” theorized Hart, “but would be the storage, retrieval, and searching of what was stored in our libraries.”

So Hart typed the Declaration of Independence into the University of Illinois’ Xerox Sigma V mainframe—a room-sized contraption that cost over $300,000 and could only store 3MB of data on its 5-foot-tall hard drive—then started typing up complete public-domain books and adding them to his budding digital library.

Project Gutenberg was founded on two of Hart’s principles: that “anything that can be entered into a computer can be reproduced indefinitely” and thus be free or nearly so, and that searching through books was as important as reading them.

The easiest-to-replicate and-search books would have to be standardized, readable by anyone with any software. That’s why books in the Project Gutenberg library—originally plain-text files, later rereleased as modern ePub e-books—are transcribed in “plain vanilla ASCII,” with only the raw text contained in the books. Even formatting is discarded, with italics and bold replaced by capitalized text.

Gutenberg e-books are the opposite of printed book norms. No one on the Gutenberg team carefully selects a typeface and formats the page margins and endnotes. These books are pure text.

That helped Hart’s vision stand the test of time. As technology evolved, Gutenberg books were able to adapt. If you read any out-of-copyright e-books today, there is a high chance it was first digitized by Project Gutenberg. (And, in fact, Gutenberg e-books helped train GPT!)

After the Gutenberg era, innovation picked up where digital books left off. Software was built to analyze the books, e-book reader apps formatted the digital text into nicer reader experiences, search engines indexed them, and vocalists recorded them into audiobooks.

It took a few decades for computers to become small enough, so people could carry them around and put them in their pockets and be able to read digital books anywhere. But the writing was on the wall. By the time the PalmPilot PDAs launched in 1997, Hart’s dream of having a free library—in your pocket, no less—was finally coming true. Commercial books weren’t far behind, with Simon & Schuster launching an e-book imprint in 1999, followed by an official Palm e-book store with over 5,000 titles in 2002.

Then came the Kindle in 2007, with a black-and-white paper-like screen to make e-books feel a bit more like print. Then came the iPad in 2010, launched with Steve Jobs showcasing how much nicer the reading experience could be on a digital tablet.

Suddenly e-books were everywhere and mainstream, the default way humanity was reading books. And yet, for all the innovation, e-books felt stuck in the past, “not much different than books,” as Ben Thompson opined. A Kindle book could never replicate the feeling of handpicking a hardcover book at a bookstore. Aside from Project Gutenberg’s free e-books, digital books often weren’t even cheaper than their print counterparts.

Was all that innovation, this time, for naught?

E-books' secret sauce = distribution and search

Along the way of commercializing digital books, with shiny new Kindles and iPads, it was easy to lose sight of what was truly disruptive about e-books: distribution and search.

Perhaps e-books are not all that different from books. Perhaps they’re worse, even, lacking that essential “bookiness.” Yet you can buy one on a whim, in the middle of the night, and start reading instantly—a distribution win that print books could never replicate. And you can search for anything in your books, the original benefit that Hart, Licklider, Busa, and Bush alike dreamed of.

While the other tech giants were perfecting the reading experience, making nicer software and gadgets for e-books, Google was one of the few companies that kept their eyes on the search value of digital books. In 2004, Google Books aimed to scan every book and journal—both in and out of copyright. Here, the goal wasn’t as much letting us read every book as it was more unlocking the ideas in the books by making every written word searchable.

Google Books’ scanned pages could be read page after page, if you’re determined. But that’s not the ideal use case. If anything, the best book pairing today would be a paper copy of a classic book alongside a phone or tablet with Google Books, Internet Archive, or Amazon’s Look Inside open. You could then lean on today’s digital tech to rapidly search the book you’re reading, and ancient tech (the book itself) to soak up the info in its raw form.

The thinkers and innovators who laid the groundwork for today’s e-book ecosystem all had the same goal in mind. Books, to them, were repositories of information. Search and replication were the goal, to unlock the ideas hidden in the pages. Fonts and formatting were secondary at best.

Reading on a screen isn’t (perhaps) better than on paper. No amount of animations or paper-like screens could replicate bookiness. Thus came the disillusion that e-books aren’t so different from books, that maybe we’re just as good going back to print.

Perhaps we’ll never make something better than a book. Humanity perfected books over centuries, and their tactile, inky pages are as close to perfect as the wheel or a spoon, a crucial human invention you can’t improve upon. But when you shed all of the baggage, when books are reduced to their words and nothing else, that’s when e-books can be something truly different and can come alive.

Which is what is happening with OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

They, being dead, yet speak: AI Dickens arrives

The innovation that has finally liberated humanity’s knowledge from pages started out as a project to build a friendly AI. What became today’s ChatGPT started out in 2015 as a project to “advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole,” a mission reminiscent of the dream behind Project Gutenberg. GPT wasn’t built as a new way to read e-books and didn’t set out to reinvent the book, yet it’s the greatest change to the book concept since a Roman put two clay tablets together into a tabula.

Today’s language-model AIs aren’t just a way to search through a book. They can read vast libraries of digital books, divine their meaning, and answer questions from the text using the author’s own words, rewritten years, centuries even, after they were first pinned.

Try opening ChatGPT or Bing Chat and asking it a question about a classic book. Moments later, you’ll get a summary of the book’s core ideas and thesis, as well as significant quotes. You can ask GPT to role-play as a book’s protagonist, acting like Sherlock helping you solve a mystery. It feels like something Sir Arthur Conan Doyle could have written himself.

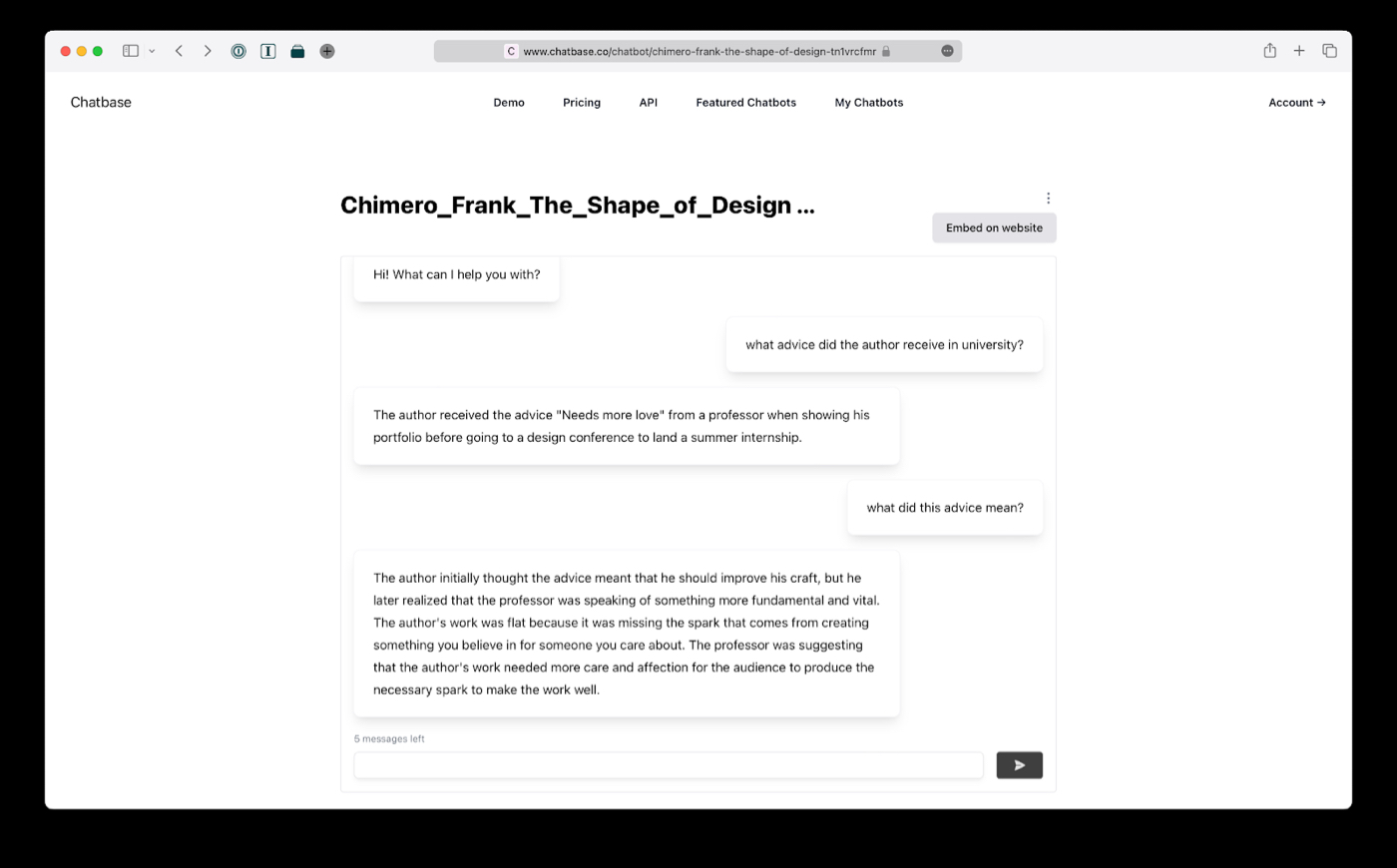

Caption: Hallucinations from a Chatbase bot trained on Frank Chimero’s The Shape of DesignIt’s far from perfect. AI still has far too many hallucinations to be fully reliable. Case in point, a Chatbase bot trained on Frank Chimero’s The Shape of Design listed 19 books when I asked it for every reference in the book. Its answers ranged from plausible options like The Design of Everyday Things to the Bible and Haruki Murakami novels (none which were actually quoted in the book). With AI today, you have to proceed with caution, but the tantalizing hint of the future is there.

That same faulty chatbot, though, was capable enough to summarize advice Chimero gave in his book and surmise what that advice meant. The AI couldn’t share a specific page, but it did guide me toward what to search. It’s a halting start at a research assistant that can help you learn more from a text while reading it.

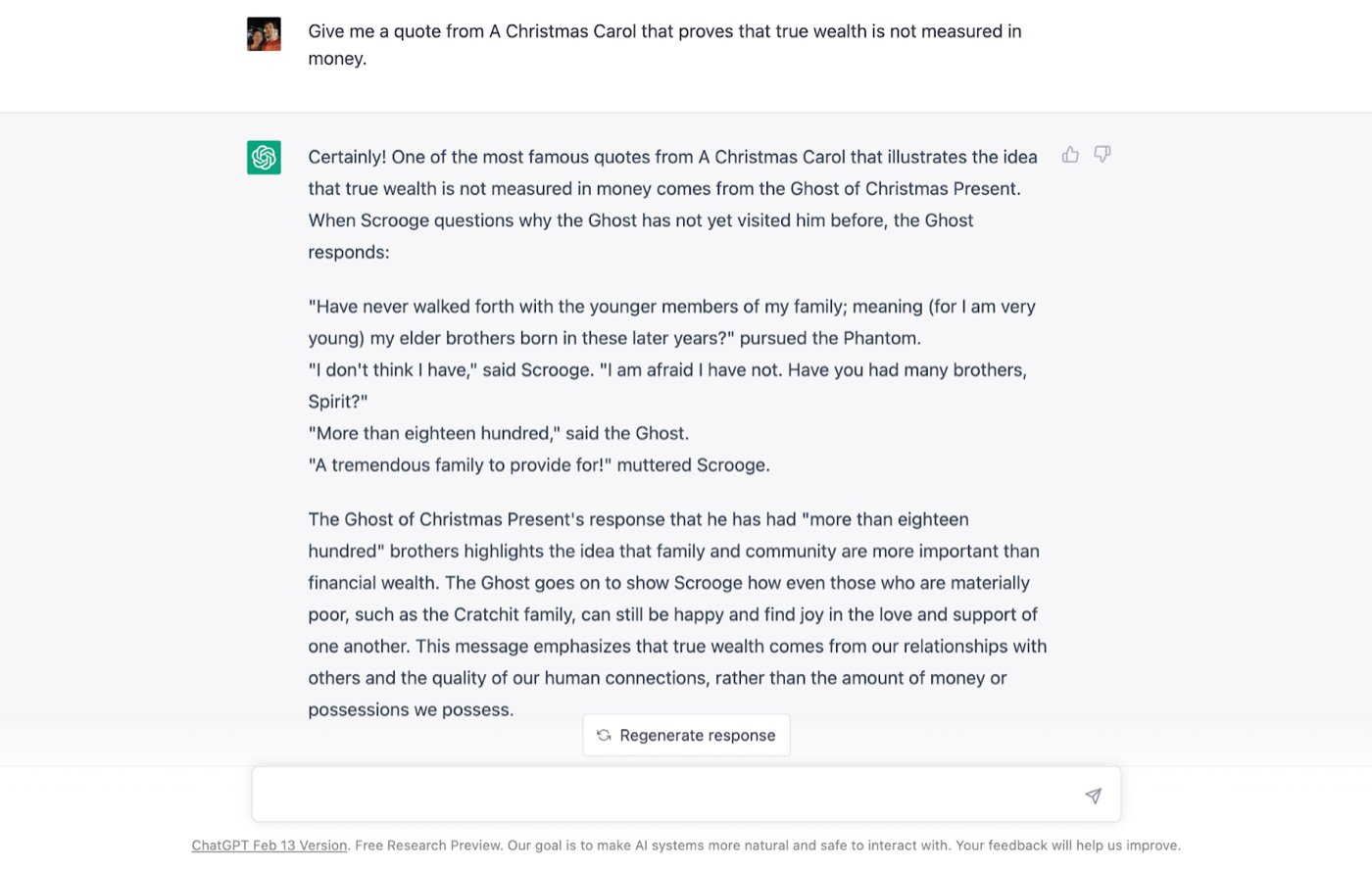

AI can surface words and phrases, but it still doesn’t truly understand what they mean. ChatGPT lacks the cultural clues often needed to divine meaning from books. For example, it misinterpreted a quote from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol about the Ghost of Christmas Present having “more than eighteen hundred” siblings to mean that family is more important than wealth, instead of the more literal interpretation that over 1,800 Christmases had passed since Dickens wrote the passage.

Yet, for all its faults, GPT let me talk to the mind of Charles Dickens, or at least the parts of it that were preserved on paper. Dickens is long gone, but his ghost still speaks, advising us on the nature of true wealth even while misunderstanding Dickens’ turns of speech.

Caption: Ghost Dickens as channeled through a ChatGPT mediumAI is the parchment-meets-tabula revolution of e-books. The first wave of parchment meant cheaper scrolls; the first wave of e-books meant cheaper books, along with perhaps easier sharing of key quotes you manually discover. The second wave married ideas from the clay tablets with parchment (giving us the notebook, then the codex, then the book). The current wave of e-books enabled search, then interactivity, then analysis—and AI has only just gotten started.

It’s only when we stripped books down to their pure words, to their essence of ideas, that we made something that’s not quite a book but is far more valuable than its paper ancestors.

Paper books were like vinyl records (to take one final analogy). You could generally figure out where a new song (or idea) started, place the needle on vinyl (or finger through the pages), and jump in midstream. You could start again later, but it’d be a bit hit-and-miss to find where you left off the previous time.

Today’s e-books are like cassette tapes. You’d start but could stop anytime to pick back up where you left off. Jumping around wasn’t so easy, but keeping going was. If anything, with cassettes, you had a better chance at restarting right where you left off listening than you did with, say, CDs.

E-books with AI are, to really stretch the analogy, the Spotify of books. They’re best chopped up, as bits of wisdom to navigate on their own.

“Even if our memory retains the content, it alters the words; but there discourse is stored in safety, to be heard forever with consistency,” continued Cassidorus’ praise of papyrus. For centuries, books have let those who “being dead yet speaketh,” as the Bible put it. However, for the longest time, the only way to get the author’s voice and ideas was to dedicate hours to reading all of it.

That, perhaps, is still the best way to retain the info, to make it a part of your mental model. And it’s why paper books won’t go away.

But e-books, now with search and AI-powered interactivity, have become more navigable than paper books. This flexibility let the book take over the scroll, and we may have just found the key innovative advantage that makes e-books more valuable than their print counterparts. We can chat with books and keep their authors’ voices alive far beyond the grave. E-books may be a poor version of books, but they’re infinitely better stores of knowledge.

Matthew Guay is co-founder of Pith & Pip, a content consultancy, and Reproof, an upcoming writing platform. Find him on Twitter.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I think an advantage of e-book and almost nobody recognize is the fact you can set the size of the page in order to read the same rate word/minutes. You can set the most confortable size to read quickest than a printable version. For non-fiction books that is an amazing feature.

@rsilvam I'd never thought of doing that—clever! I think my favorite thing is that I love highlighting e-books and then copying the quotes out on another device later. I hate messing up the pages of a print book, but have no such qualms with e-books.

@maguay I agree. Is one of my favorites features too. I have my kindle highlights linked with a Readwise account, so you can organize them better even export to another platform like Notion, etc. The taking note process is another topic that deserves a separate article, because has its own evolution process as the book itself.

This is really great article! I love it! The best article of this month.

Memo to myself: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=GEDK05Ko2yVhDGJM2KAv