How to Build a GPT-4 Chat Bot Course

We just re-launched our How To Build a GPT-4 Chatbot course taught by Dan Shipper!

It's an online cohort-based course that will teach you how to make your own GPT-4 based knowledge assistant in less than 30 days. It runs once a week for five weeks starting September 5th. It costs $2,000, but you can get a 15% discount if you are an Every paid subscriber. Want to learn to build in AI?

About 15 years ago, tech investors began pouring their money into a new business model: B2B subscriptions. It may not have been flashy, but it bore fruit: across many different problem areas, subscription software sold over the internet produced dominant new tech companies—like Shopify for selling products online and Zendesk for managing customer support. Even incumbents like Adobe and Microsoft rebuilt their businesses around these subscription models to unlock new growth.

Unlike most trends in tech that start on the consumer side and then migrate into B2B over time—think of mobile apps or great user experience design—the subscription model did the reverse. B2B subscription models started to take off after the IPO of Salesforce in 2004 and the launch of AWS in 2006, and then-startups like Shopify (founded in 2006), Dropbox (2007), Zendesk (2007), Asana (2008), and Slack (2009) grew quickly thereafter.

In the wake of those companies’ success, founders started adapting consumer software to subscription models, initially on the web and increasingly mobile-first after Apple’s App Store debuted in 2009. The breakout year for consumer subscription models was 2011, when Duolingo, and physical grooming and beauty product companies Dollar Shave Club and ipsy, respectively, were all founded; Spotify launched in the U.S.; Amazon introduced video for its Prime customers; and Netflix’s stock grew propulsively after a decade of mediocrity.

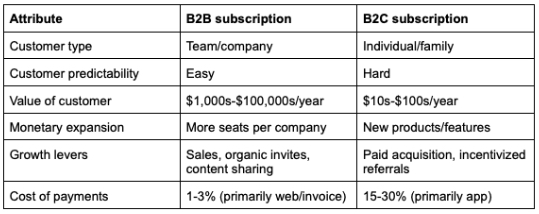

But while founders and venture capitalists would preach the gospel of predictable revenue and sustainable growth, outside of the big three—Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify—consumer companies have largely under-performed their B2B counterparts over time. This chart, which illustrates the differences between the two models, hints at why:

I was the chief product officer at Eventbrite, a business that launched its first B2B subscription product a couple years ago. I’m also a board member of Beek, a B2C subscription audiobook company, and I’ve advised many companies across both models. So I’ve had to confront their differences many times firsthand. I’ll dig into the reasons for the disparity in their performance, and then explain how to produce superior returns in the consumer subscription category.

Unlock the power of AI and learn to create your personal AI chatbot in just 30 days with our cohort-based course.

Here's what you'll learn:

- Master AI fundamentals like GPT-4, ChatGPT, vector databases, and LLM libraries

- Learn to build, code, and ship a versatile AI chatbot

- Enhance your writing, decision-making, and ideation with your AI assistant

What's included:

- Weekly live sessions and expert mentorship

- Access to our thriving AI community

- Hands-on projects and in-depth lessons

- Live Q&A sessions with industry experts

- A step-by-step roadmap to launch your AI assistant

- The chance to launch your chatbot to Every's 85,000 person audience

There are limited seats so sign up now to take advantage. Learn to build in AI—with AI in just 30 days!

The key feature of the B2B subscription business model

The pessimist would argue that the B2B subscription business isn’t that successful, either, and more so only looked good during a zero-interest-rate environment, when “seat growth” (i.e., companies expanding the use of a subscription product by buying more seats as they hired more employees) was a given for most of your customers. But the B2B subscription model has some durable advantages that will play out even in the weakest of markets compared to many other business models.

The average VC tweet storm or LinkedIn thinkfluencer will say that it’s all about predictable revenue, but that’s at too high a level to be instructive. Revenue isn’t that predictable; what does improve predictability is that your customers are more rational in their decision-making. You can evaluate which potential customers will become solid sources of revenue and generally won’t be surprised by their usage of a product, their growth of seats/plans, whether they’ll go out of business, etc. Most of these customers are sizable enough that the revenue from them creates sustainable growth levers, whether it be sales-, product-, or marketing-led growth—and sometimes a combination of the three.

More importantly, when customers do grow, they create a phenomenon known as net dollar retention. In any B2B subscription business, some customers will churn. But the ones that do retain tend to invest more in your product over time, growing revenue per customer in a way that covers more than the churn of other customers. In many new B2B subscription companies, their seats/usage are contracting for the first time due to fears of a recession, but outside of some bad years, net dollar retention will be a core feature of their growth model.

What’s different in consumer subscription?

Churn is higher, average revenue per customer lower, and net dollar retention non-existent

Consumers are not rational. It is hard to predict who will stop using your product and who will build habits around it. So, on average, churn in consumer subscription businesses is a lot higher.

In addition, the amount made per customer tends to be significantly lower as consumers have, on average, less spending power than businesses. And even when you effectively activate consumers into paying users who build habits, you don’t increase the amount of money you make from them over time outside of raising prices (like Spotify and Netflix just did). Net dollar retention, the best feature of a B2B subscription growth model, is not even present in a consumer subscription growth model.

The consumer subscription products that have been the most successful at scale have spent an incredible amount on content to prevent churn. These are companies like Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify. That amount of spend on content is usually not replicable for startups.

Payments are less optimized and more expensive

The margin structure of consumer businesses is hampered compared to their B2B counterparts because mobile apps are the most dominant product experience for consumers. App stores (primarily Apple’s) take a significant percentage of subscriptions purchased through them and prevent alternate forms of payment to avoid that tax.

To make matters worse, app stores are also much worse at collecting payments. One way growth teams of B2B companies help improve their companies’ performance is by addressing involuntary churn through payment failures. Not only is Apple not nearly as good at this as, say, payment companies like Stripe and Adyen, but because it controls the entire experience, your growth team cannot optimize the payment flow and retries to improve the payment failure rate. Fortunately, the stranglehold on in-app payments is starting to break, such that consumer companies can improve payment conversion on the mobile web while increasing margins at the same time—but it’s been a drag on an already difficult business model.

Customer acquisition is much harder, less scalable, and has fewer options

B2B subscriptions are sold to teams and companies at scale. Consumer subscriptions are sold to individuals and, at best, families. Think of buying Slack or Asana versus buying Calm or Duolingo. We already know that means that the average order value for the latter is lower, but there are also ramifications for customer acquisition loops: selling directly to users via a salesperson is out of the question due its cost as compared to the return of a subscription. Some of the viral and content loops in B2B subscription—like sharing a file, or inviting a coworker to collaborate or chat—aren’t possible in consumer products. This mainly leaves paid acquisition as the lever for growth.

Every company uses paid acquisition to target its best potential customers first, which usually creates a healthy payback period—i.e., the amount of time it takes a startup to recoup its marketing cost of a user with the profit they eventually make the company. But to scale, the company needs to target more and more customers who look less like the core customer over time. Those customers fare more poorly on every metric: ad response, conversion on the landing page into trials, conversion from trials to subscriptions, and retention after subscribing. This leads to predictable degradation in payback periods year over year until, eventually, you run out of people to acquire profitably and paid acquisition is no longer viable. And in the meantime, Apple decided to torpedo all the ways you track effectiveness of paid acquisition, too.

When I was an investor at Greylock and we were evaluating investing in the series A for meditation app Calm, the churn of users acquired via paid acquisition is what spooked us. At the time, Calm had only decent annual retention. We could model out a time in the future when it would be impossible for the company to grow based on its current numbers.

Today Calm is one of the few companies to improve its annual retention over time. It did so by pursuing one of the solutions I offer below.

How to overcome the systemic challenges of consumer subscription

Despite these inherent difficulties, there are solutions to these problems. Let’s dive into the best ways to mitigate these limitations and create big outcomes.

1. Leverage network effects to solve retention and acquisition issues

Network effects allow your core product experience to get better faster than the customers you acquire get worse. Subsequent generations of consumer subscription businesses create product experiences that improve over time either by leveraging the data of their users or by offloading content creation costs to suppliers. Duolingo has done a masterful job of retaining users in a space with normally high churn because its language lessons get better every day based on the feedback loop of its customer usage. We call that a data network effect. Spotify has exponentially more types of content (music, podcasts, video) and artists than when it launched, all of which attracts more listeners. That’s a cross-side network effect.

Startups like Beek and social reading app Fable continually add new content creators on their platforms who either improve the quantity of content available or aid in the discovery of existing content for consumers, which keeps them subscribed. Furthermore, those creators make money based on the app’s subscription revenue, so they become both promoters of the app and a significant source of low-cost acquisition. These companies can rely a lot less on paid acquisition, and some don’t even have it as part of the customer acquisition mix. There are many more opportunities to create multiplayer consumer experiences to drive low-cost acquisition and better subscription retention because your friends or family keep pulling you back into the app. These exist mostly in the games category today.

2. Go multi-product earlier in your lifecycle to make the product stickier and raise the price

It’s very hard for single-product solutions to maintain long-term retention without network effects. So if network effects don’t make sense for the type of product value you’re delivering, launching new products to better monetize your existing customers and open up new customer segments can ease the burden on customer acquisition, raise monetization rates, and increase retention all at the same time. Calm was able to scale its Sleep Stories product in a way that raised the retention rate of its meditation customer base as well as open up segments that were less interested in meditation. It turns out that selling a product solution for something people have to do everyday (sleep) has a much bigger market than a habit a small percent of the world does (meditation).

3. Open up less saturated acquisition channels

Most consumer subscription businesses treat their content as their proprietary secret sauce, keeping it under lock and key inside paid subscriptions. So that content isn’t doing all it can to attract new customers who are not even aware of your product.

Masterclass is a great example of a company that re-uses a lot of the amazing content it sells in its courses by repackaging it for search engines as a taste of what the full courses offer. A company that historically grew mostly via paid acquisition diversified its acquisition sources, brought down payback periods, and found new audiences. Spotify’s playlist sharing was a key growth driver in its early days as lists were shared among friends and publicly on the internet. Spotify and Hulu have also bundled their subscription models to find new audiences and improve retention for both products.

Thinking about new platforms as well as channels can work, too. Most subscription businesses start as apps, but the web opens up a new acquisition channel with significantly better margins because you don’t have to pay the in-app purchase tax. Many of the companies I’ve worked with have found ways to get conversion on the mobile web just as high as in-app over time, or at least use annual subscriptions to dramatically improve payback periods.

4. Start selling to businesses (you knew this was coming, right?)

This one is obvious, and basically the same suggestion as number three: creating a B2B offering allows you to target a new customer business with a new acquisition loop in sales that can acquire hundreds to thousands of people at the same time inside companies. Headspace and Calm have done a good job of expanding into this model from their consumer roots.

Be forewarned: these solutions aren’t a panacea, and they may not make a meaningful enough improvement to take your consumer subscription business beyond scale. Many of the companies I mentioned still may not succeed in the long term. I advise founders to think through these challenges and opportunities during the zero-to-one phase of building so that they’re not surprised at how hard things will be in the growth stage. Consumer subscription is a very hard business to scale toward a venture outcome, and you want every possible thing you can to be working for you because so much of the default business model works against you.

But when it works, the venture outcomes can be tremendous. Duolingo is worth $6 billion at the time of this writing, Spotify $33 billion, and Netflix $190 billion. Those numbers rival even the best B2B subscription companies—so keep building.

Casey Winters is a startup executive who most recently was the chief product officer at Eventbrite. He also serves as an advisor to, and a board member of, technology startups. This piece was originally published on his website.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Good read. I learned a lot.

"But while founders and venture capitalists would preach the gospel of predictable revenue and sustainable growth, outside of the big three—Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify—consumer companies have largely under-performed their B2B counterparts over time." - I didn't know this.

"Some of the viral and content loops in B2B subscription—like sharing a file, or inviting a coworker to collaborate or chat—aren’t possible in consumer products. This mainly leaves paid acquisition as the lever for growth." -> Why is this impossible?

My learnings: https://share.glasp.co/kei/?p=2NamroxVNpJRX58SuklK