Hello, Every readers! Today we're excited to bring you a piece by researcher and writer Lewis Kallow. Lewis believes that there is a lot that founders and operators can learn from elite athletes. For this piece, he looked at ultramarathon runner Courtney Dauwalter, who won a 240-mile ultramarathon through the desert in 2017. He unpacks the mindset that Courtney built in order to perform at her peak through the pain and exhaustion caused by the extreme conditions of the race. Plus, he discusses the science behind the tactics she used, and how you can apply it to your own life.

We hope you enjoy it!

Moab, Utah is a popular setting for sci-fi films. That’s probably because it literally looks like another planet. It’s home to giant red rock archways, gaping canyons, mysterious craters and plenty of dinosaur bones. It’s also the staging ground for one of the country’s toughest ultramarathons: the Moab 240.

The Moab is two hundred and forty desert miles of rocky mountain climbs and endless dirt roads. It can get as hot as 97°F (36°C) during the day and as cold as 15°F (-10°C) at night. The race takes the average competitor 90 hours to complete. It’s so long that the distance between two checkpoints can be more than an entire regular marathon’s length. Runners are regularly afflicted by sunburn, intense physical pain, crushing fatigue, and hallucinations, with some even reporting blindness.

And yet, in 2017, Courtney Dauwalter somehow made it look like a cakewalk. Not only did she win—she set the record for the race, and finished ten whole hours ahead of the next runner.

Stranger still, Courtney has no specific plan or training schedule. Not even a coach. She eats whatever she wants, including right before a race. Pre-competition meals have included pizza, waffles, and McDonald’s.

Now, obviously Courtney does train with high intensity and has an abundance of athletic talent. But perhaps the reason Courtney doesn’t need the fancy running gear or militant regimens is because she has something else that is critical for endurance: unstoppable mental resilience.

During her races, Courtney deploys a handful of mindset techniques that allow her to stay in charge of her mind and body for hundreds of miles. These same techniques are now being validated across new studies at the frontiers of psychological science.

They’re also universally applicable. Whether you’re running an ultramarathon or running a business, you somehow have to sustain your energy over long periods of time, deploy creative solutions to unexpected problems, and find a way to keep going when it all feels like too much.

The same tools Courtney relies on to out-will the desert sun can also help you hold the line during a tough project, conversation, or workout. So the plan for today is to break down four of Courtney’s tactics, explore the evidence behind why they work, and then give you some ideas for implementing them in your daily life so you can become a lean, mean, persevering machine.

I. Embrace the Pain

Your brain is hardwired to avoid pain and seek pleasure. This single drive is so powerful that it’s sculpted every aspect of the modern world. From our temperature controlled buildings, to our home delivered food, to our infinite libraries of entertainment beamed down from the sky, we’re now surrounded by miracles designed to make every aspect of our lives comfortable.

Courtney, however, has learned to completely flip this instinct on its head. What she craves is discomfort. When things get tough during a race, Courtney enters what she describes as the “pain cave”. She uses visualization to picture herself in a cave with a hardhat and chisel, and as she pushes through the pain of the run, she imagines chiseling tunnels through the rockface. Pain is gradually chipped away into progress as her cave gets bigger and bigger.

“I believe that when we go in the cave, we can work to make ourselves better, and when given the opportunity—I always go in.”

— Courtney Dauwalter

With this simple visualization technique, pain ceases to be something to avoid or simply tolerate, and instead becomes a welcome opportunity. Most of us arrive at the cave’s entrance with dread, but for Courtney, it’s where the real work begins. She has mastered the ability to take the discomfort associated with a goal and reframe it as a positive sign of growth.

Recent studies have confirmed that this strategy is a powerful driver of persistence and motivation. One such study was published in March 2022 by two of the world’s leading experts on motivation and goal pursuit: Kaitlin Woolley of Cornell University and Ayelet Fishbach of the University of Chicago.

The first of their five experiments took place across fifty-five improvisation classes at Chicago’s Second City—the comedy club and improv school that helped to train the likes of Steve Carell and Tina Fey.

When a group of budding improvisers were instructed to interpret any awkwardness or discomfort they experienced as a sign of progress, they suddenly persisted 44% longer than a control group. They were also judged as bolder risk takers by outside observers and reported higher feelings of progress after the class.

Trying to improvise on the spot with no preparation to a room full of strangers can be a deeply uncomfortable experience. But by encouraging the participants to see their discomfort as an indication of growth, they were able to stay in their real world pain caves for longer.

The same persistence-enhancing effects of embracing discomfort were observed in Woolley and Fischbach's remaining experiments across several other domains:

- When they asked participants who were writing about a difficult emotional experience to embrace discomfort, those participants felt a deeper sense of emotional growth from the exercise and were more motivated to work through challenging emotions in future.

- When they asked Republicans and Democrats to embrace discomfort while reading an opposing political viewpoint, they were more open minded and more motivated to understand the other side’s perspective.

- And when they asked participants to embrace discomfort while learning about a difficult topic—gun violence—they were more motivated to learn new information and read more deeply about the subject.

So what’s the mechanism at play here? Well, reinterpreting discomfort as growth is a form of cognitive reappraisal—the deliberate act of changing the way you think about something in order to change how you feel. Reappraisal is one of the strongest tools in your toolkit for emotional regulation: your ability to influence which emotions you feel, how long you feel them for, how intensely you feel them, and the way in which you express them.

Reappraisal works simply because your feelings about the situations, people, and subjects around you are influenced by the way you think about them. Change the way you think and you can change the way you feel.

In each of these examples, by “reappraising” discomfort as growth, people are ditching their belief that discomfort is a sign to quit, and replacing it with the belief that discomfort is a sign to lean in and press on. This new appraisal softens feelings of discomfort, facilitates emotional regulation, and thereby boosts persistence.

“Once I changed my storyline around pain, I was able to celebrate it rather than just try to survive it.”

— Courtney Dauwalter

We enter mini pain caves every day, whether it’s a tough conversation, resisting temptation, staying positive, sustaining focus, or finishing a workout. Our most valuable skills, achievements, and growth lie deep within the cave, and changing how we perceive the cave makes it that much easier to enter and lay hold of its inner treasures. The next time you find yourself faced with discomfort in pursuit of a goal, greet the cave with open arms, pull out your trusty chisel, and start digging.

(Note: Discomfort is not the same thing as extreme physical or emotional pain. Courtney does not push through any pain that she believes will cause serious long term injury. Pushing past limitations should always be done with safety in mind.)

II. Make the Here and Now Awesome

The next thing that makes Courtney so strange is that she’s happy. At least, happier than one would expect her to be given the sleep deprivation, physical agony, and hallucinations. Both on and off the trail, she is famed and admired for always having a smile on her face and maintaining a cheery disposition.

Courtney will tell herself jokes, pause to give people high fives, daydream about eating nachos on the beach, and sometimes will just simply breathe in and enjoy the scenery. She makes the experience joyful wherever and whenever possible.

“No matter how serious the training is, there’s always time for lounging and playing”.

— Courtney Dauwalter

Psychologists and behavioral economists would argue that Courtney’s playfulness gives her a competitive edge. That’s because enjoyment is a powerful but massively underrated driver of perseverance.

In 2016, another study from Kaitlin Woolley and Ayelet Fishbach found that students who were given snacks, colored pens, and music persisted with their math problems for significantly longer than a snackless, penless, musicless control group. Another study found that watching Animal Planet videos helped people brush their teeth for 30% longer than those who watched a comparatively boring video. A third found that people go to the gym more frequently when they combine their workout with an interesting audiobook.

More fun = more persistence. Why? Because it provides your brain with immediate rewards rather than it having to rely exclusively on distant rewards. Finding an activity immediately rewarding turns out to be one of the biggest determinants of perseverance that psychologists have uncovered.

Woolley and Fischbach highlighted the significance of this effect in a series of five experiments in 2016. They tracked how well people persisted with a whole host of different activities, including New Year's Resolutions, eating more vegetables, sticking to a workout routine, and studying for an exam.

Then they subjected everyone to a battery of tests to determine the degree to which people were motivated by the long-term outcome of a given activity (e.g. getting an A grade, losing weight) versus how immediately rewarding they found the activity (e.g. interested in the current subject material, enjoying the taste of healthy food).

In each of Woolley and Fischbach's experiments, immediate rewards and enjoyment were around three times better at driving persistence than distant rewards! The people who studied the longest, worked out the most, and ate the healthiest were the ones who found those activities the most intrinsically rewarding. They have reliably replicated this effect across numerous studies since.

Understanding and leveraging the power of immediate rewards is essential for sustaining long-term motivation. There are months of training and hundreds of miles between Courtney and the finish line—that distant reward by itself is not going to be enough.

The mechanism we have to thank for this is delay discounting: the phenomenon where the subjective value of a reward declines as the time until its arrival increases. Generally speaking, the further you push a reward out into the future, the less certain we are that we’ll actually get it, and the less motivating that reward becomes.

(If you’d like to read more about delay discounting, check out this great research paper or this one)

In light of such a risky time delay, your brain will often veto your long-term hopes and dreams in favor of lying on the couch. But if you can offer your brain some rewards now—like having fun or following your intrinsic curiosity—then it’s much more likely to play along. Courtney’s unique ability to find joy along the path and to use creative tactics that make the process more rewarding is undoubtedly a critical part of her superhuman endurance.

Nathan Barry, founder of ConvertKit, recently asked Andrew Gazdecki, the founder of MicroAcquire, what secret strategy he used to grow his Twitter following from 30,000 to 70,000 in six months. Andrew responded, “So, Twitter strategy… there is absolutely none, aside from having fun,” and then continued: “If you want to be great at anything, you just have to enjoy it and then if you enjoy it you’re consistent at it.”

(Andrew has since grown to over 140k followers as of writing)

Whether it’s growing on social media, eating your greens, or running a marathon, finding ways to make the pursuit immediately rewarding is the key to driving persistence:

- You’ll probably be better off learning how to make healthy food taste great instead of dreaming about the perfect body.

- You’re more likely to feel motivated by the project that piques your interest than the one you think will look good on your resume.

- Your odds of lasting in a relationship that brings you happiness is better than the one that looks good on social media.

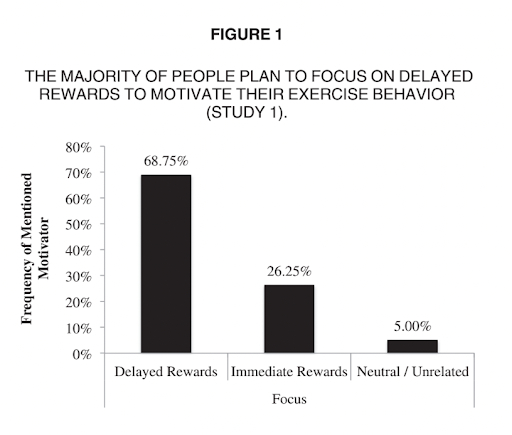

Now this is all well and good except for one slight problem: most of us seem hellbent on completely ignoring this principle. See, the professors also exposed the trap that many of us fall into—most of the study participants told Woolley and Fischbach that they believed distant rewards were a superior source of motivation! Even many of the most persistent participants (those who were deriving the highest level of immediate rewards from their activity) still said they planned to rely on distant rewards to motivate themselves moving forward:

Woolley, Kaitlin, et al. (2016)

Most of us have this natural tendency to overly obsess over the outcome—the promotion or the beach body or the big sale—and to neglect the joy of the journey, thereby undermining our ability to actually make it across the finish line. What this means is that we may have to pay extra close attention to whether we’re neglecting opportunities to make the current phase of our journey more rewarding.

Fortunately, once you start actively looking for ways to make the here and now more awesome, there are all kinds of techniques you can use to make any process or pursuit more rewarding. Here are a few examples supported by the literature:

- Temptation Bundling: Combine something you enjoy with something you find hard. For example, listen to your favorite podcast while cooking a healthy meal.

- Situational: Find a pleasurable environment. For example, work on your difficult work task at a new coffee shop.

- Social: Team up on something difficult with someone who’ll make the experience more immediately rewarding. For example, workout with a friend.

- Psychological: Reframe goals in a way that makes them more immediately rewarding. For example, break a task or activity into smaller pieces and then embrace the immediate satisfaction of hitting those targets.

Let’s not dismiss distant rewards entirely though. Even though immediate rewards are better at driving consistent action and persistent effort, distant rewards still have a valuable role to play. Woolley and Fischbach have found that having a big future goal that’s meaningful to you can increase your intention and desire to pursue it.

Distant rewards can help to set you up with strong intentions and then immediate rewards will allow you to back those intentions with consistent action. Why not give yourself the best of both worlds?

Map out a compelling five year business plan and find a way to enjoy the day to day operations. Get excited about looking and feeling great as you age and also cultivate a fun workout habit. Feel determined to cross the finish line ten hours ahead of the next competitor and stop to give people high fives.

This short-term orientation toward playfulness combined with the long-term desire to win is like rocket fuel for endurance. From the 2016 study:

“Whenever people are intrinsically motivated to pursue activities that are associated with long-term goals, they receive immediate and delayed rewards from the same action, and pursuing long term goals no longer poses a self-control conflict.”

When your day is full of actions that provide you with both delayed and immediate rewards, goal pursuit starts to feel a heck of a lot less effortful. I suspect that this is the secret behind the most hardworking, persistent, and highly-motivated individuals—they make it look easy because they’re fueled by a compelling destination and an enjoyable journey.

But wait, doesn’t having fun contradict the idea of embracing discomfort? When it comes to optimal performance, there’s a subtle balance to be struck between embracing discomfort and yet not experiencing it any sooner than necessary. Courtney knows she’ll reach the pain cave eventually, welcomes it, and has tools to navigate through it, but I imagine that by injecting fun and enjoyment along the way, she doesn’t spend any more time in there than necessary, ultimately arrives there later than her competitors, and experiences more overall stamina as a result.

It’s this combination of leading with pleasure first and then leaning into pain when it eventually arrives that will optimize your maximal endurance. So the next time you find yourself approaching your pain cave, try sprucing it up a little first! Light a fire, bring a comfy sofa, mount a 50” TV on the wall, and invite your pals around.

III. Get Some Space

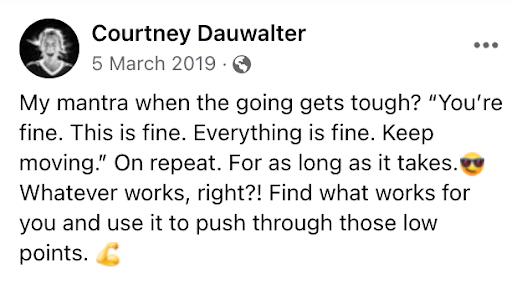

During an interview with Runner’s World, Courtney revealed the mantra she repeats when things get hard:

“You're fine, you're fine, you're doing fine, this is fine.”

There appears to be some variation but it generally involves telling herself that she’s fine on repeat.

Another runner in the comments section of the above post shared their own similar mantra: “This is easy! Just one step at the time. You just need to keep moving. No matter how slow, just keep moving!”

You may have noticed a peculiar quirk to the language used in these mantras: they all use the pronoun “you”, almost as if they’re talking to someone else. Is there a method in this madness? You bet.

Using “you” instead of “I” when talking to yourself, or calling yourself by your own name, is an example of “distanced self-talk”. A large body of evidence has been stacking up to suggest that this deceptively simple technique can help you tap into your deeper willpower reserves.

Ethan Kross is a leading expert on the power of self-talk. He breaks down this science for us in his acclaimed 2021 bestselling book Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It. In one chapter, Kross describes how he used distanced self-talk to help study participants endure heightened stress.

When participants rocked up to Kross's lab for the study, they had a bit of a shock—they were informed there and then that they were going to be doing some public speaking!

Their task was to deliver a speech about why they were qualified to land their dream job to a panel of experts. Not only would these experts be assessing their performance, the whole thing was going to be filmed. Oh, and they only had five minutes to prepare. Starting right away! Yeesh.

These participants had just been unknowingly subjected to one of the most powerful strategies that researchers have at their disposal for ethically inducing stress in humans—having to perform under social pressure with insufficient preparation. Now it was time to find out if self-talk could help people rise to the challenge.

Once the five minutes of preparation were up, participants were divided into one of two groups. One group was asked to spend several minutes thinking about their thoughts, feelings, and experiences about the upcoming performance in the first person (e.g. “I” feel nervous).

The other group was asked to think about their feelings using the pronoun “you” and their own name. For example, if your name was Jane, you might say to yourself, “Alright Jane, how are you feeling?” or… “Okay Jane, you’ve got this.” Sounds crazy, but once again, this single, simple, shift made a world of difference.

As Kross predicted, the participants who used distanced self-talk reported being much less nervous and saw the whole thing as less of a big deal. The judges, blind to which group each participant was in, rated the performances of the distanced self talkers as having superior to the “I” group. Plus, the distancers experienced less shame and embarrassment once they were done with their speeches. They dwelled on the experience less and had fewer counterproductive thoughts after the fact.

Another experiment in the same study found that people who used distancing before meeting a stranger went on to make better first impressions. Many more brilliant studies have found similarly beneficial results for all manner of endurance challenges:

- Psychological distancing strategies have been found to enhance the ability to maintain self-control in the face of temptation and stick to a healthy diet.

- Distanced self talk can help us view future stressors as challenges rather than threats, leading to a more adaptive cardiovascular stress response.

- Couples who adopt a distanced perspective stay together longer on average and have more forgiving and less blameful arguments.

And, as Courtney intuited, athletes who talk to themselves using non-first-person language perform better on tests of stamina and power.

Now, you may be wondering why this works. Fortunately, in 2017, Kross and his colleagues hooked participants up to a brain scanner to provide the answer. When people used distancing language to reflect on their feelings, the emotional activity in their brain radically dampened down.

It’s easier, on a neurological level, for you to guide yourself through tight spots when you talk to yourself as though you’re someone else—allowing you to perform better and persevere for longer than you otherwise would.

Crucially, the emotional relief happened in less than a second, proving that distanced self-talk is an excellent tool for alleviating discomfort in the heat of a moment, precisely when we need it most.

Try it out for yourself the next time you need to coach yourself through something challenging, just like Aaron—a participant in one of Kross's studies—when he was steeling himself ahead of a big date:

“Aaron, you need to slow down. It’s a date, everyone gets nervous. Oh jeez, why did you say that? You need to pull it back. Come on man, pull it together. You can do this.”

IV. Collect Your Evidence

When Courtney hits a particularly tough spot in a race, she will occasionally travel back in time. She will remind herself of a moment when she overcame a similar obstacle to the one she’s currently facing.

“I’ll remember back to when I’ve been in the same boat and got through it. Remembering the evidence that this is something you have been through before, helps you to keep pushing and know it will be fine.”

— Courtney Daulwater

This process, which Courtney refers to as “collecting evidence," is a great way of convincing yourself that you have what it takes to stare down whatever hurdle is in front of you. Thinking about your previous successes and reminding yourself that you’ve “got through worse” can put your current situation in perspective and serve as a formidable source of strength.

There’s a fascinating biological mechanism behind evidence collection which opens up the door to a host of other similarly useful tactics. It’s a mechanism which has been observed across many studies but one of the strongest demonstrations emerged from an experiment in 2021.

Conducted by Jeremy Jamieson—who runs the Social Stress Lab at the University of Rochester and whose work has informed much of what we know about the harmful and enhancing effects of stress—the study aimed to find out whether Jamieson's research could help community college students prepare for their upcoming math exams.

Students were broken into two groups and then left to complete their first of three exams without interference. But then, ahead of their second exam, Jamieson gave one group an intervention which was designed to influence the students’ mindset.

He taught this group that any signs of stress they experienced around the exams (like increased heart rate or feelings of anxiety) were actually there to help them. He explained that their stress was in fact giving them extra energy, sharpening their focus, and supplying their brains with more oxygen.

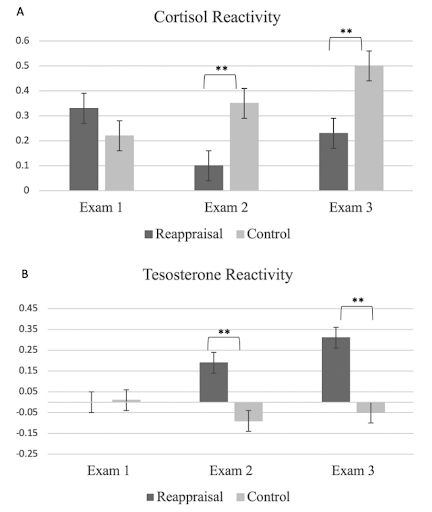

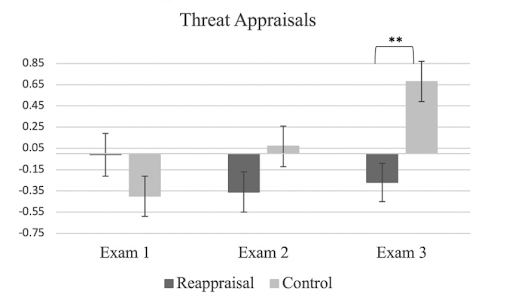

Across the next two exams, striking differences emerged between the two groups as a result of the intervention. Firstly, the two groups exhibited completely different hormone profiles in response to the exam stress:

As you can see, the group who received the mindset intervention (again, before their second exam) had substantially lower cortisol reactivity, and much higher testosterone reactivity. This drastic shift in cortisol and testosterone hints at the two fundamentally different ways that our bodies can respond to stress.

The students in the control group with higher cortisol and lower testosterone were displaying what researchers call a “threat response”. It’s well established that this biological stress response sabotages our performance and damages our health and well being. It produces a rise in “catabolic” hormones—like cortisol and cytokines—which are associated with inflammation, breakdown, and many of the long term health issues we’ve heard tied to stress.

The mindset group, meanwhile, suddenly mounted what’s known as a “challenge response”—their hormone response flipped as their cortisol reactivity cooled off and their testosterone reactivity amped up. Contrary to the threat response, our challenge response acts as a performance enhancing drug. It makes us more confident, focused, resilient, and fosters a bias for action.

Your challenge response allows you to get all the benefits of stress while protecting you from its negative consequences. It does so by producing “anabolic” hormones—including testosterone but also others like estrogen and human growth hormone—which counteract the catabolic effects of cortisol. Jeremy calls this “the biology of courage.”

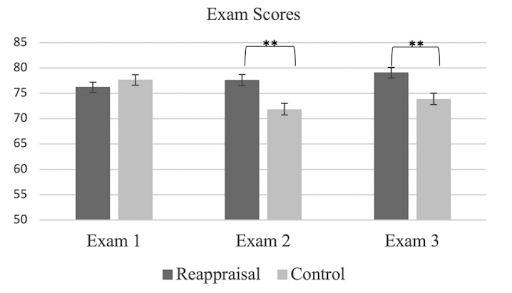

The mindset shift had caused a powerful biological change, and then that biology translated into several important real-world outcomes. Armed with their newfound challenge mindset, the students experienced a significant performance boost and scored higher on their two post-intervention exams:

They also felt better. People experiencing a threat response often report emotions including fear, anger, and self-doubt. But the challenge group felt less anxiety and were much less threatened, an effect that got even stronger over time:

It turns out that stress feels exciting and energizing when it’s experienced as a challenge, spurring us to take charge and move forward. This was reflected by the challenge group procrastinating less and having a more proactive and action-oriented approach to their studies after learning that stress was useful.

And, crucially, the challenge group were more persistent with their studies, as reflected by stronger course retention, with 90.2% of the mindset group finishing their course but only 78.8% of the control group.

Which leads us back to Courtney and her evidence. How does all of this relate?

Well, Jamieson found something interesting when he looked at why the mindset intervention was so effective. It turns out that the biggest factor which determines whether we adopt a challenge response or a threat response is all about how we perceive our situation. More specifically, how we feel about the demands of a situation relative to the internal/external resources we have to handle it.

For example, if you look at your to-do list in the morning and feel as though you’ve got what it takes to put a solid dent in it, what you’re really saying is that you believe your resources are sufficient to meet your demands. In response, you’ll feel all “I’ve totally got this," and your challenge mode will get unleashed upon your tasks.

However, if you feel as though your demands overwhelm your abilities, like when you’ve barely had any sleep the night before and your inbox is full of emails from co-workers saying things like “Any updates on this…?” then you’ll feel all “I don’t got this” and the threat response kicks in.

But here’s the most important part: your perception of your demands and resources seems to matter even more than your actual demands and resources! By teaching the students that their stress was helpful, the intervention simply nudged the students into believing that they could handle the demands of their situation. After all, they didn’t make the students any smarter or teach them some secret study technique. They just changed their perception.

Courtney’s evidence collection strategy works in the same way. By reminding yourself of previous successes, you make yourself feel as though you totally have what it takes. You stop your body from sliding into threat mode which protects you from the catabolic effects of stress and fuels perseverance.

Of course, there are times when you really can’t handle the demands put upon you, no matter which way you look at it. You need to find a way to either lighten your load, get some more support, or quit. But we can also underestimate what we’re really capable of and often have more strength available to us than we realize.

Sometimes the best way to weather a crisis, or navigate a conflict, or survive a trough of sorrow is to use techniques that remind your brain you can still handle the heat. Understanding this principle unlocks a host of evidence-based strategies that will put you into a “resources=sufficient” mindset, for instance:

- Focusing on your strengths

- Thinking about how you have prepared for a particular challenge

- Imagining the support of your team, friends, and/or loved ones (Courtney has a whole team to help with logistics and pacing, including her husband, Kevin Schmidt, who even once ran the last 30 miles of a race with her!)

- The knowledge that others are praying for you

During the period I was writing this, the first ever direct evidence that gratitude can activate a challenge response was published. When teams reminded each other of a time they were grateful for something their partners did ahead of a business pitch, they expressed the biology of challenge rather than threat.

You don’t just have to rely on your own victories when it comes to evidence collection either. Thinking about what other people have historically made it through can also work: “If Courtney can run two hundred miles then I can run five. If Thomas Edison survived his factory burning down then I can handle losing a client.”

Whenever you can do something to convince yourself that you have what it takes, you help your body respond to stress as a challenge rather than as a threat, and your performance, endurance, and health flourishes as a result.

All of this research comes together to offer a host of simple but profoundly useful questions you can ask yourself during trying times:

- How is the discomfort you’re facing right now going to help you grow?

- How can you make this experience more immediately rewarding?

- What evidence do you have that you can handle this?

- What resources do you have—strengths, preparation, or social support—that can help you rise to the demands of your current challenge?

- Have people survived this challenge or similar ones in the past? How did they respond?

(And of course you get bonus points for asking yourself those questions with some self-distancing by using the word “you” or your own name!)

The Finish Line

Your discomfort isn’t a defect. It’s usually there to help protect you from physical or emotional harm. But running away from it can hold you back from becoming your boldest and most fully-actualized self.

The next time you experience the feeling, and you probably won’t have to wait very long, remember that it’s a normal part of the process. Better yet, do what Courtney would do, pull out your chisel and see it as an opportunity for growth.

From there, remember that you have distancing tools to keep yourself in check. Try getting some space by changing your self-talk. Keep yourself in challenge mode by thinking about your previous successes, your preparation, your strengths, and the support of others.

Finally, remember to find the fun wherever possible. Actively work to make your journey enjoyable now rather than later.

According to the wisdom of modern psychology and one of the greatest endurance athletes the world has ever known, you’ll be much better equipped to run the ultramarathon of life.

This post was written by Lewis Kallow of Super Self. It was edited by Katie Parrott.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

What an insightful article! So many nuggets in here to takeaway from this. Mental models galore and biohacks that are effective in the classroom, the boardroom, on the court and in the wild. Thanks Lewis and Katie for this wonderful post!

This is a wonderful piece. Love the sentiments but also the research and science... How can this be shared on platforms like LinkedIn?