Sponsored By: AE Studio

This essay is brought to you by AE Studio, your custom software development, and AI Partner. Built for founders, AE helps you achieve rapid success with custom MVPs, drive innovation, and maximize ROI.

Three straight weeks of 110-degree temperatures in Phoenix. Deep freeze in Texas. A sweltering heat wave across nearly a third of the country. America’s power grid is under unprecedented strain from extreme weather caused by climate change—and it desperately needs modernizing.

But it’s not so simple. The electric grid is a mosaic of incredible feats of engineering—an elaborate web weaving together power from nuclear reactors, massive hydroelectric dams, and even solar farms into a network capable of powering our homes and charging our cars instantly and reliably.

And it’s easy to take for granted. When we first discovered how to use electricity, it was an open question as to how replenishing electric power should happen. One option, about which I previously wrote, involved the use of battery men who would deliver weekly supplies of electric power like milkmen once did with milk. There were even visions of giant acid battery tanks buried beneath homes that could be replenished like septic tanks.

Instead, the system that eventually won out was Thomas Edison’s. The most efficient system was one that could generate electric power as needed and transmit it instantly—no delivery men required.

It would take decades to be built out fully, but as it grew to encompass more and more of the North American continent, the model of distributing electric power from plant to home transformed society and our economy. Yet for all the transformations the electric grid wrought, it is now time for the grid itself to transform if it is going to keep pace with the rapidly changing nature of power generation and electricity usage.

Such transformation, however, poses an unprecedented challenge. The flip side of the grid’s impressive complexity is the difficulty of altering any part of it. And although the electric grid is the very system powering the U.S. economy, it is also becoming the country’s greatest bottleneck in increasing the abundance of energy.

Let’s explore the current state of the electrical grid, how it works, and its history, and its future.

Are you ready to take your business to the next level?

AE Studio can help you achieve your goals faster than the competition with our custom software and AI solutions. We work closely with founders and executives to understand your needs and create a solution that is tailored to your success. Whether you need an MVP to test your idea, or a custom AI solution to drive innovation, AE can help.

We are the world's most effective team of developers, data scientists, and designers. We have a proven track record of success, and we are committed to helping you achieve your goals.

Schedule a free scoping session today to see how AE can help you transform your business.

The electrical grid today

There’s not just one grid supplying electric power within the United States—there are four.

Source: SimpleThread

The Eastern, Western, Alaska, and Texas interconnections (i.e., grids) are collectively composed of over 11,925 power plants, 160,000 miles of high voltage lines, and many millions of miles of distribution lines that reach like tiny tendrils into even the most rural parts of the country.

Taken together, North America’s power plants have the ability to generate roughly 1.2 billion kilowatts of power at any given time. If all the plants were to run continuously for all 8,760 hours in a year, America could supply something like 10.5 trillion kilowatt hours of electric power. Although it’s not practical to have all of the plants operating around the clock since that would overload the system, this would be the hypothetical ceiling of America’s grid generation capacity.

Currently, annual consumption of electricity falls around 4 trillion kilowatt hours in the U.S—or roughly equivalent to having all of America’s power plants operating 30% of the time.

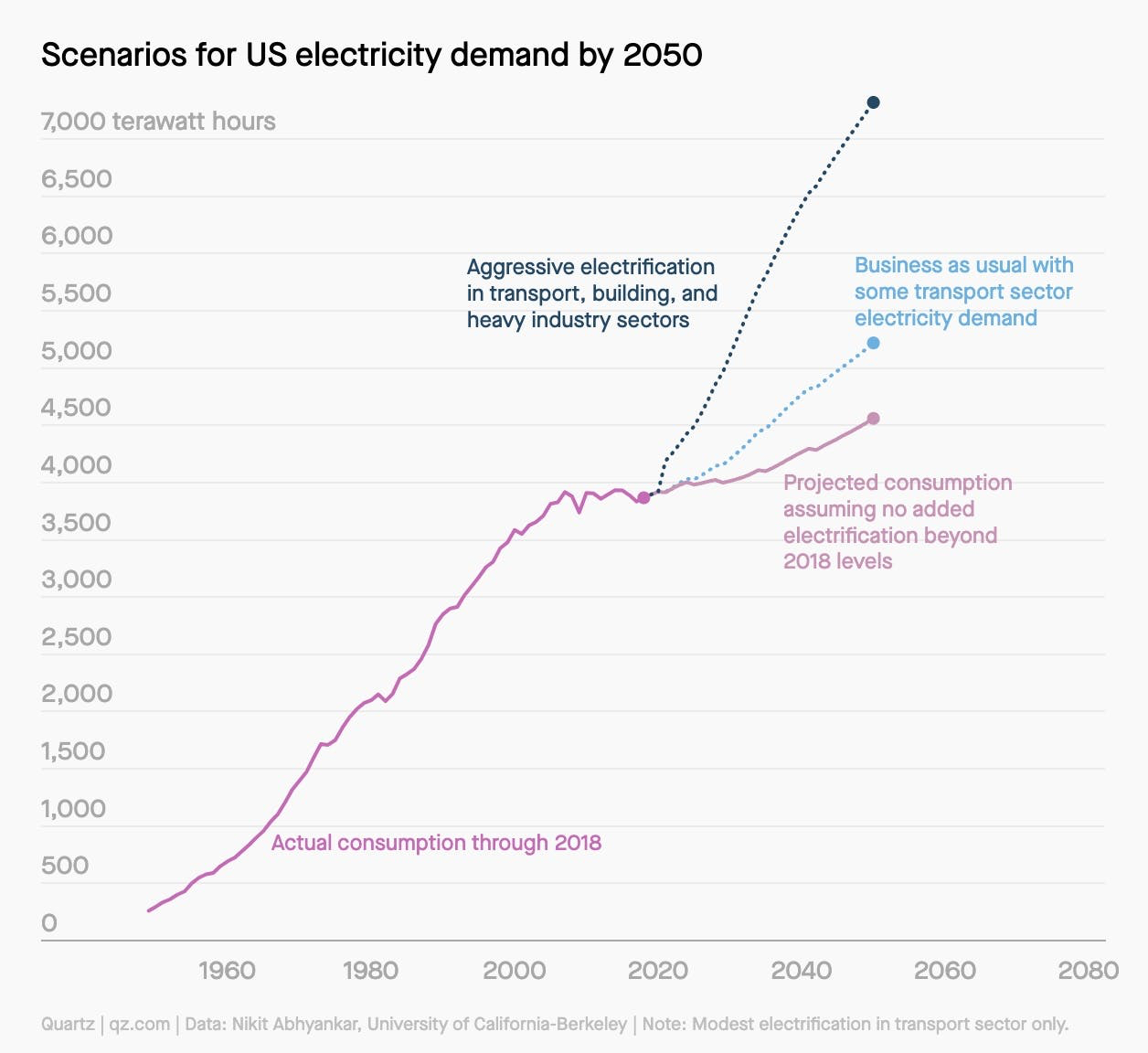

However, in the coming years, the consumption of electricity is anticipated to increase greatly, particularly due to the growing number of electric vehicles.

EVs consume a lot of electricity. An EV’s battery can store the equivalent of an average American household’s daily electric power consumption two or three times over. If EV owners charge to full from 50% each day, a household with an electric vehicle will now be consuming twice as much electricity as it did before. And as states like California have mandated that all vehicles sold in the state after 2035 must be electric, it’s becoming increasingly urgent to ensure that the grid will actually be able to supply the additional power that this will require.

Source: Quartz

There are varied estimates for exactly how much electricity consumption will grow over the next 30 years. In the event of aggressive expansion of electric vehicle use, some estimates put total U.S. energy consumption 90% higher than current levels by 2050. More conservative accounts place that figure somewhere between 15%-35%.

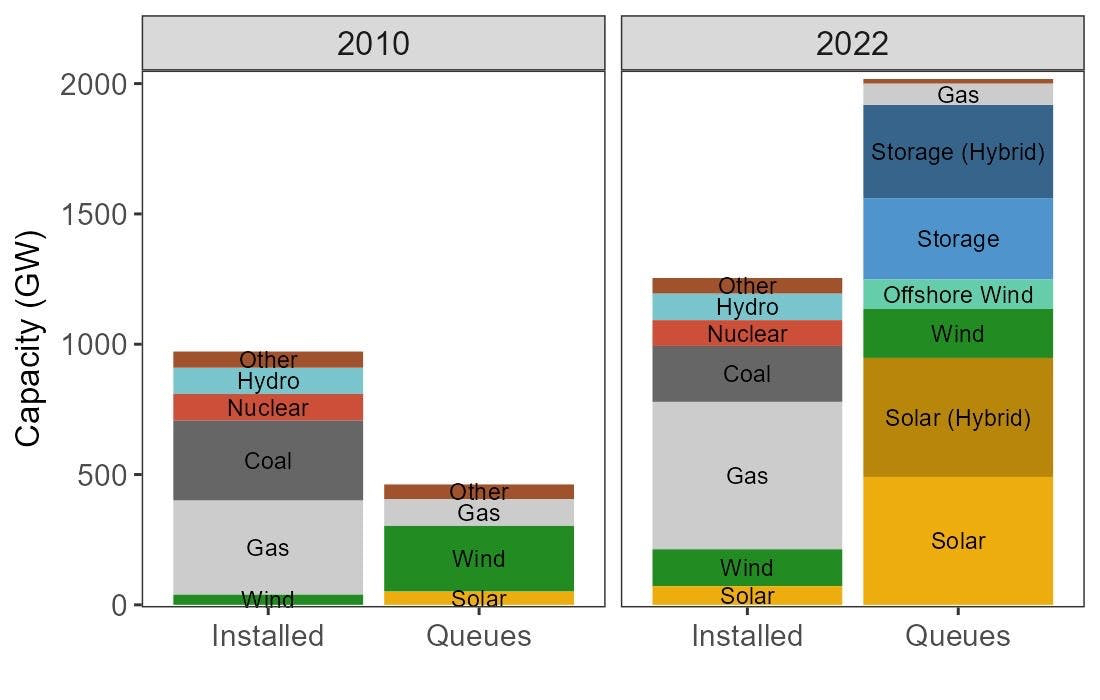

Confronting a possible 90% increase in electricity usage would require a large build-out of additional generating capacity, especially if we don’t want to overload the grid. Many will be surprised to learn, however, that there are already over two terawatts of proposed new power generation waiting to come online in interconnection queues. This delay is the result of proposed power generators needing to hear back from regulators and other stakeholders about how and when their generators could be connected to the grid, how much it would cost, and who would be able to pay.

So the only thing standing in the way of the United States producing three times as much power in the next couple of years is not the scarcity of renewable power generation, but rather the regulatory and logistical bottleneck of connecting this new power to the grid.

Source: Electricity, Markets and Policy. Berkeley

The increased demand for green power generation is also reflected in the queue of proposed projects. The vast majority of them are solar or wind plants. In fact, there’s more solar and wind generation in the queue than the total current supply of power coming from natural gas and coal. To be clear, many of the proposed projects in the queue are just that—proposed. Only a portion of them are expected to be built. For others, the cost and time required to hook them up to the grid will render many of the projects uneconomical.

But it’s not just green energy incentives contributing to a growing queue of proposed projects—it’s also growing wait times in the interconnection queue. As it stands, it can take five years to hear back from grid operators. In states like California, it often takes many more.

To be fair, solving the interconnection challenges for many of these proposed projects is a difficult challenge, requiring new designs to be drawn up and different scenarios to be investigated. Still, the growing queue and daunting wait times indicate that it’s not just building green energy generation that’s the problem—it’s connecting it to the existing grid.

Before we get into the details of grid interconnection, let’s review how the grid currently operates.

How the grid works

At its most fundamental, the grid can be broken down into three components: power generation, transmission, and distribution.

Power generation

The central nodes of all electric grids are power generators. These are the nuclear plants, coal and natural gas plants, hydroelectric dams, wind turbines, and solar farms. Jointly, they tie together not only the electric grid but also the industrial economy, supplying power for all of our daily domestic and commercial functions.

Remarkably, despite the gargantuan size of the grid itself, it’s designed to supply power instantaneously. The second you flick a switch to turn on the lights, power generated only a moment ago is now lighting your home. Until very recently, the grid didn’t have the means to store any power that it produced, which meant any excess electricity generated would go to waste. This meant the equilibrium state of the grid was for the total amount of power generated to exactly equal all the power being consumed by households and businesses.

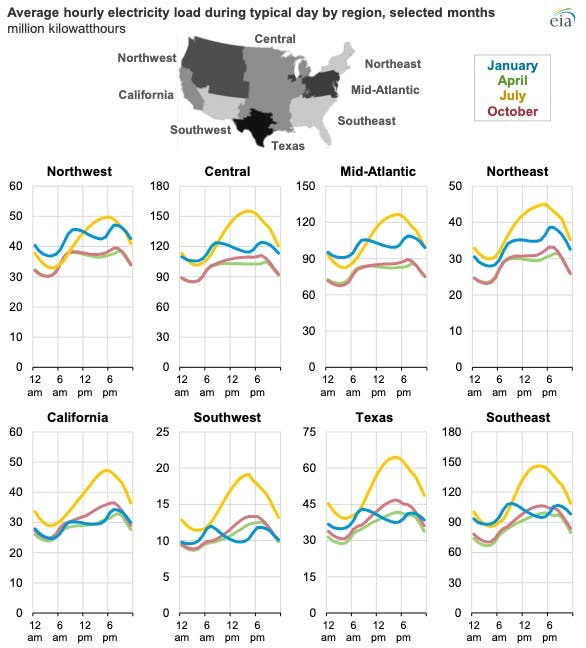

However, keeping the supply of electricity in lockstep with demand is not straightforward. Power consumption fluctuates during the day, just as it does seasonally. So, to regulate the amount of power supplied through the grid, power generation needs to be flexible. Operators need to be able to turn generators on and off to accommodate changes in demand. Doing this is easier for some generators than it is for others. For example, it takes a large amount of energy to turn a nuclear plant on, so once a nuclear power plant is producing a sustained reaction, it doesn’t make economic sense to shut it down to accommodate fluctuating demand. As a result, nuclear plants make up what’s called the “base load of power” in the United States. Coal plants are another example of baseload generators since, once the coal in a plant starts burning, it’s rather inefficient to put out the fire. Together, these plants operate constantly, supplying the minimum amount of power needed throughout the day.

Source: Energy Information Administration

Natural gas plants, however, can easily be turned on and off. It’s just a matter of turning the gas valve—hence why natural gas plants are effective at meeting fluctuating demand during the day. Natural gas can be burned in the daytime when electricity consumption rises and turned off at night when the workday is over, and everyone’s lights are off.

All of the generators mentioned above require inputs to power them—whether that’s uranium, coal, or natural gas. However, those inputs are predictable. If we know how many inputs we have, we know exactly how much power we’ll be able to generate over a given time.

On the other hand, the growing number of renewable energy sources require no inputs to generate electricity. They produce power on nature’s timetable. When there is wind, when there is sun, there is electricity—and vice versa.

Not needing any inputs to generate electricity is a great economic feature of renewables, but also makes their generation of electricity hard to predict. Integrating them into a grid requires a delicate balance between power supply and demand, which is a complicating factor for bringing renewable energy sources online. Indeed, the challenge of integrating renewables is becoming one of the biggest financial and industrial challenges of our time.

Transmission

Most people don’t realize that the generators households rely on are often extremely far from those households. A complete journey between a base load power generator, such as a nuclear or coal plant, and the end consumer could range anywhere between hundreds to thousands of miles. That’s a lot of distance, and the further electricity travels from its point of generation, the more energy is lost in transit to heat dissipation. The transmission component of the grid is one of the most important and ingenious, since it allows this massive system to work economically and efficiently.

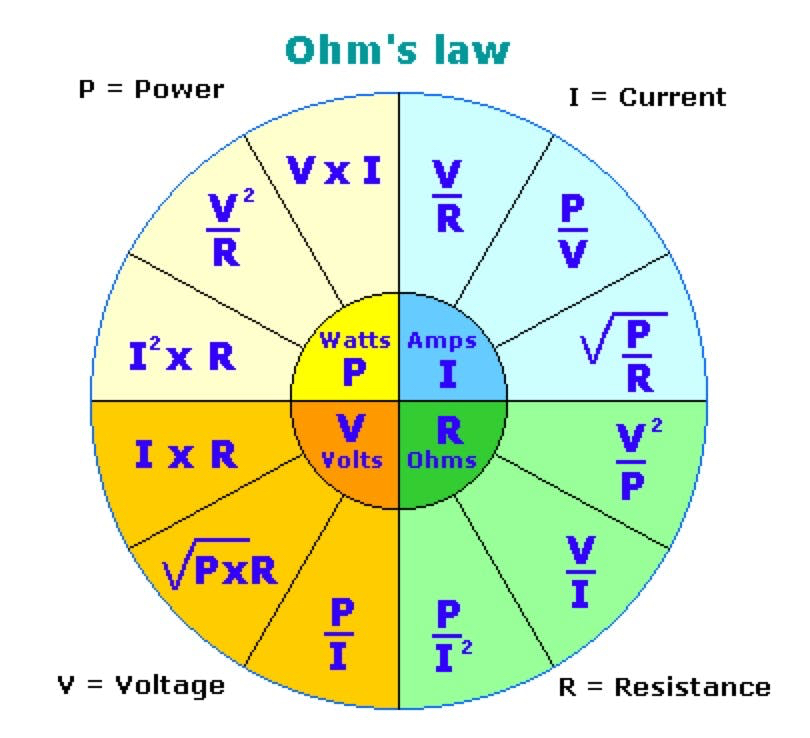

An electric plant generates a certain amount of power per unit time. That electrical power, or the amount of work that electricity can perform per some unit of time, can be represented as the current, or the rate of electron flow per unit of time, multiplied by the voltage.

P (power) = V (voltage) x I (current)

The formal definition of voltage is the difference in electric potential between two points. However, what that quantity really represents is a kind of electric pressure inducing electrons to move from an area of higher voltage to an area of lower voltage. The higher the voltage, the more the electrons want to travel. When there is voltage, or a difference in electric potential between two points, there is an electric current. When there is no voltage, there is no current.

With that said, the goal of every power generator is to maximize the amount of power delivered to the end user and minimize the power lost in transmission. The power loss formula, which states that the power lost in transmission is equal to the current squared multiplied by the resistance of the conductor, shows how such loss can be prevented.

P (power) = I^2 (current squared) x R (resistance)

Resistance is a measure of conductivity. Non-conducting materials, like wood, have high resistance, so they make for poor conductors. Metals like silver and copper are very good conductors, with little resistance. It’s worth mentioning that the quality of resistance is crucial to the use of electricity in the first place. The ability of materials to convert electricity into light or heat is entirely thanks to resistance. In fact, all devices that draw energy from a current, like appliances and machines, which convert electric energy into light or heat or mechanical motion, are all just big resistors.

Source: Electronics Tutorials

Minimizing resistance in transmission is simply a matter of choosing the right materials. The factor most important in diminishing power lost is the current. The higher the current, the worse, because a higher current means more electrons interacting with the resistance of the wire, leading to greater energy loss.

To summarize, decreasing power loss hinges on minimizing the current passing through the transmitting conductor. Going back to the electric power formula, we also see that we can still transmit the same amount of power when we lower the current by increasing the voltage.

This insight is the key behind all long-distance power transmission. In fact, it’s the insight that makes long-distance power transmission possible.

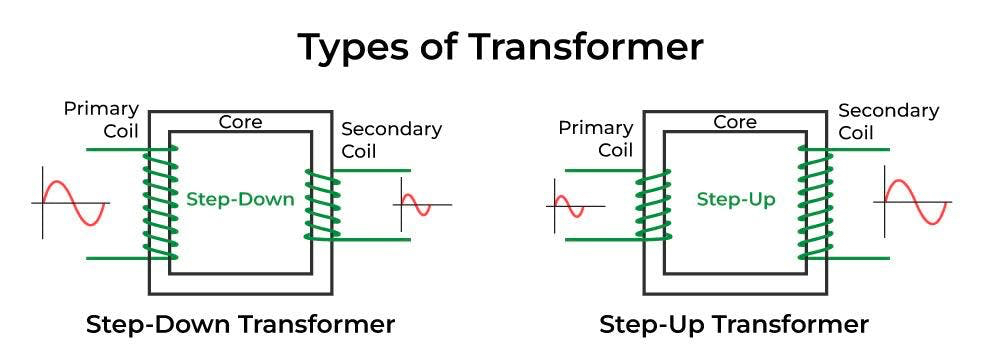

The transformer is essential to large-scale electric transmission. Transformers are clever devices that increase voltage by passing an alternating current from a primary coil to a secondary coil. The genius of this device lies in the fact that the number of coils in the windings corresponds exactly to the step-change in voltage achieved. If there are 10 times more coils in the second winding, the voltage will also increase by a factor of 10.

Source: GeeksforGeeks

Power plants typically generate electricity at a low voltage, somewhere between 10 and 30 volts. Even compared to the 120 volts that outlets produce, that’s pretty low. Before being fed into long-distance transmission lines, the generated electricity needs its voltage raised by a factor of around 100,000. In the U.S., super-high-voltage transmission lines carry a voltage anywhere between 750 kilovolts to 1200 kilovolts.

High voltages also make these wires dangerous. The electric potential in them is so great that even the air around them becomes ionized. Thankfully, air is a poor conductor of electricity, so the layer of ionized air actually acts as an insulator, like the plastic around a cable. However, that disc of ionized air is still conducting some electricity, so it needs to be kept as far away from the ground as is feasible. For this reason, high-voltage transmission lines are between 50 to 180 feet above the ground.

Given that any number of events could easily interfere with the proper operation of these wires, from falling trees to lightning strikes, the lines need to be monitored constantly. Sophisticated switches and circuit breakers are implemented throughout to isolate damaged lines.

Distribution

Once power has been ferried long distances through high-voltage channels and gets closer to the end consumer, it is routed to local substations that funnel the electric current through transformers again, this time to bring the voltage down. Due to the lower voltages, it’s practical to insulate these lines, which is why pigeons can sit on distribution lines without being electrocuted. Ultimately, the lines connect directly to service lines, which feed electricity into our homes at 120 volts.

A brief history of the grid

Building infrastructure to span the entire country and interconnecting each electric plant to each home was never an obvious design decision. Indeed, its history was fraught from the beginning with competing ideas and characters.

There were two key scientific discoveries, however, that made the concept of “electricity as a service” possible. The first was Michael Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction. In 1831, Faraday realized how to instrumentalize the relationship between electricity and magnetism. He found that by creating an alternating magnetic field, achieved simply by spinning a magnet, an electric current could be induced.

The second was Werner von Siemens’s invention of the dynamo in 1866. Faraday’s discovery was crucial to the design of the dynamo, which was a machine capable of using mechanical power (spinning a magnet) to induce a current and produce electric power. It was a crucial invention that later filled all electricity-generating plants of its time—and still does today.

All the pieces were there, but it would take another 50 years before the emergence of the first commercial power station. Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Station, a coal plant built in 1882 in the heart of New York City’s financial district, was the first of its kind. It connected via transmission wires to a set of private customers and supplied a direct current used by customers for lighting, operating telegraphs, and telephones.

Just four years after the unveiling of Edison’s power plant, a rival system reared its head. George Westinghouse, a Pennsylvanian engineer and inventor, realized the limitations of Edison’s system. Edison’s direct current (DC) electricity couldn’t travel very far, since over great distances, too much power was lost in transmission, rendering the venture uneconomical. Edison’s customers would have to be very close to the source of generated power.

Westinghouse realized that a possible solution would be to use alternating current (AC). Alternating current differs from direct current in that its electrons flow back and forth rather than unidirectionally. The alternating flow of the current creates alternating electric and magnetic fields that have many useful properties. Since the alternating current already possesses an alternating magnetic field, the alternating current itself could be used to induce electric currents in nearby devices.

Westinghouse realized that this property of AC power is essential since it meant that AC power could be used with transformers to increase or decrease voltage. Voltage could be increased to more efficiently deliver electricity to consumers, and then it could be decreased ahead of delivery.

Westinghouse’s system began delivering power to customers further and further out, threatening Edison’s designs which relied on DC power. To combat Westinghouse’s superior model of transmission, Edison launched a public smear campaign against AC power now called “the war of the currents.” He claimed high-voltage AC was dangerous and a threat to consumers. The one issue standing in Westinghouse’s way was that most devices were designed to use direct current, but that problem was resolved once Nikola Tesla invented a functional AC motor, settling the war of currents once and for all.

Over the following years, the number of independent power companies grew at a dramatic pace. Utility-scale electricity production grew over 70 times between 1902 and 1942. However, the disjointed nature of the power supply meant that electricity from utilities was not always reliable. A slowing river’s flow could impact the amount of electric power a hydroelectric dam generated, and if that dam wasn’t connected to other generators that could pick up its slack, the dam’s customers would be out of luck. The problem became increasingly acute around the time of the Second World War, when the federal government mandated interconnections between utilities to maintain resilience during wartime manufacturing.

In time, in order to expand access to electricity to all national customers, not just those who lived in dense areas, the government allowed electricity providers to have indefinite monopolies over certain geographic regions as an incentive to provide electric coverage to more rural regions. The grid went from being a high-competition private industry to a government-regulated utility. The centralized management meant that larger and more expensive capacity plants alongside longer distance high voltage transmission lines could be built.

The future of the grid

Since the days of Edison and Westinghouse, electricity generation and consumption have changed drastically. We discovered that electricity generation doesn’t need to rely on combusting fossil fuels like coal and natural gas. Dynamos can be turned by wind turbines. We even discovered that dynamos themselves aren’t always necessary, as power can be harvested directly from the sun’s rays. As renewable energy sources like solar and wind become cheaper to install, many are eager to see the share of electricity produced via fossil fuels fall, and yet the composition of America’s energy sources has stayed fixed over the past decades. This is the case even despite a growing number of businesses eager to build out solar and wind farms across the country and the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which has allocated $400 billion in federal funding for clean energy. So, what gives?

At its core, the question of integrating renewables into the grid is one of the biggest challenges of our time. A grid built on balancing power supplied with power demanded is hard-pressed to onboard renewables that generate electricity on a schedule that has no regard for the consumption habits of users. To see why this can be a problem, one simply needs to look at the example of Texas, a grid that relies heavily on unpredictable solar and wind power, which can spike in generation at times when power demand is very low. On numerous occasions, the excess of power in Texas’s grid has resulted in negative electricity prices—beneficial for consumers, but damaging for power suppliers.

In general, there are two approaches to solving these problems. The first approach simply involves moving excess energy out of areas that don’t need it to areas that do. In the event that Arizona is overproducing power from its solar farms, would it be possible to somehow transmit that power to a cold and overcast Vermont? One of the reasons that doing so is difficult is, of course, because of America’s separate grids. Though America’s Western and Eastern grids are technically connected, they’re linked together by seven transmission lines, collectively capable of transmitting only 1.3 gigawatts. Recall that the total U.S. energy capacity is about 1.2 terawatts, around 1,000times greater than this. If any meaningful amount of energy is to be shuttled from the west to the east, or vice versa, a larger build-out of high-voltage transmission lines will be needed.

However, currently, the U.S. isn’t building any new high-voltage lines. At most, it’s only replacing existing ones. It’s understandable why this is the case. Building out more and longer transmission lines is extremely expensive. By some estimates, building out enough transmission lines to efficiently shuttle all the new renewable power coming online by 2050 would require investments of $20-30 billion per year. Not to mention that the prospect of transforming our fragmented grids into a single continental grid is fraught with political snares and regulatory hurdles.

The second approach involves storing excess power generated by renewables in batteries or other clever mechanisms, like pumped hydro storage, which pumps water up to a high elevation when power is plentiful and releases it downhill in times of power shortage. As made evident by Casey Handmer, whereas transmission lines shuttle power through space, batteries shuttle power through time. This means they’re one of the few technologies capable of helping consumers achieve massive cost savings on power since users can charge the batteries when electricity is cheap, and feed it back into the grid when electricity is in high demand.

Though batteries are by no means cheap either—back-of-the-envelope math suggests that the cost of giving each American household a battery wall unit, conservatively priced at around $8,000, would cost something on the order of a trillion dollars—Casey suggests that the ability to conduct price arbitrage on power would make up for the cost of the battery in just over a year.

The proliferation of batteries is in fact already happening, although somewhat indirectly. Everyone might not be getting a dedicated wall-mounted battery, but an increasing number of households are getting electric vehicles, which are basically extremely powerful batteries on wheels. These days, top-of-the-line EVs can have a battery storage capacity of up to 100kWh, which is three times the daily average household electricity consumption. It’s possible to imagine households charging their cars at night when electricity is cheap and then drawing from car batteries to power their houses during the day.

Though this is a clever solution, it would make other planning efforts harder to achieve. As the number of private energy storage solutions increases, predicting consumer electricity demand would become much more difficult.

Large-scale improvements in battery technology will surely have a massive impact on the evolution of the grid, but innovations in cheaper and faster transmission may also have a large role to play. Imagine if someone discovered a new method to cheaply produce superconducting materials. That would certainly change the cost estimates of building long-distance transmission lines. Since the resistance in these kinds of wires would be zero, there would be no power loss, regardless of the current or voltage flowing through them. The lines would be cheaper to produce and, most importantly, safer. As of July 2023, however, the jury is still out on what it might take to achieve such materials.

The electric grid, while powering our economy, presents a significant bottleneck in modern times. The emergence of new electric power sources, from micro-nuclear to fusion reactors, holds promise, but their potential remains unrealized without seamless grid integration. Swiftly building and updating the grid to accommodate these innovations is crucial for unlocking cheaper and more abundant energy solutions.

Anna-Sofia Lesiv is a writer at venture capital firm Contrary, where she originally published this piece. She graduated from Stanford with a degree in economics and has worked at Bridgewater, Founders Fund, and 8VC.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Great article. Would like to have seen a discussion of the LCOE for generation methodologies, impact of regulatory barriers and subsidies. Liked that you touched on base load generation, one of the key issues to be solved is replacing hydrocarbon base load gen with either renewables, which requires development of new battery technology, or nuclear, which requires regulatory change. Grid connected storage could fundamentally change the peaker market. Also important to understand that there isn’t one grid, but multiple (ISO-NE, PGM, ERCOT, et al) and that cross connections are very challenging. Sorry to ramble but I’m on a train not writing a white paper!

@gabriel.galanski thanks Gabe! really glad you liked it. I've shared your comment with Anna-Sofia, I really appreciate you leaving it :)

Great article!

@boywonderdesigns glad you liked it!

Interesting

Basic information. Non political but practical.

Great article and great information. Some additional information:

Home solar has the potential for providing distributed power right where it is most needed to charge EV’s and run air conditioners during the day. It also takes a load off the step-up, high tension transmission, step down, local distribution system by bypassing it altogether. Any excess energy ends up transferring directly to neighbors. Unfortunately, PG&E in California has just rendered home solar economically non viable as of April 15, 2023. Before that homeowners received 30-40 cents per KWh for energy exported to the grid and paid the same for energy imported from the grid. Now homeowners receive 3-4 cents per KWh for exported energy while still paying 30-40 cents per KWh for imported energy. That means there is no longer any way for home owners to recover the $20k-30k costs of a home solar system installation. No rational homeowner looking past the slick presentations at the real costs would elect to install a solar system now.

Batteries are currently more expensive than PG&E. Consumer prices for batteries to store rooftop solar and power EV’s cost about $600 per KWh hardware and installation. A typical battery is capable of about 300-500 cycles. Even doubling that to 1000 cycles results in a cost of about 60 cents for each KWh stored over the life of the battery. That makes it cheaper to buy the energy from PG&E than store it. So batteries are presently only economically useful off grid. Or essential in rural areas as an insurance policy for powering the lights, refrigerators, and wells during blackouts, particularly during blackout during wildfires when water is critical to defend the home.

So using batteries for storage and arbitrage of home solar energy won’t make any sense for a long time. And home solar is installation is likely to grind to a halt in California, except for the 4 KW systems mandated by code in new construction.

Well written! What is the status of improving electrical transmission capability via replacing existing conductors with high tech designs capable of carrying more current? The designs exist, and would allow increased capacity using existing infrastructure (i.e., current rights of way, towers, etc.). This has been a tested and proven improvement but not sure why it hasn't been pursued on a large scale.

Wasn't aware of how much legislation and red tape was holding up modernizing the grid.