Adyen means “start over again." In 2006, a group of entrepreneurs, including Pieter van der Does and Arnout Schuijff, founded Adyen. They chose the name “Adyen” because the same group founded Bibit, a payment company, and after selling the company to Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), they decided to start another payments company. Why? Pieter explains in this podcast:

“Our idea was to build in-house something that connects directly to the endpoint of payment and does not make a patchwork of systems. We believed that if you could make this product of the highest quality possible, then you’d be able to sell it to the best companies in the market. So we had a very unusual market entry strategy and a very ambitious plan: we know this market, we're going to build something that outperforms, and we directly target the high-end.”

After bootstrapping the company for almost five years, Adyen’s founders raised their first VC round in 2011. Adyen also broke even in the same year, so it wasn’t like they were under any pressure, which is perhaps the perfect time to raise money. As internet companies were in the gold rush to expand globally in the last decade and half, Adyen was ready to provide them with the shovels of payments, which can be incredibly complex even though it may appear relatively simple for the end consumer. The complexity of payments helped Adyen’s team,as they had been involved with payments since the ‘90s and had very clear ideas and vision of what internet-scaled companies really need. One of their early backers labelled the founding team the “Navy Seal team of payments."

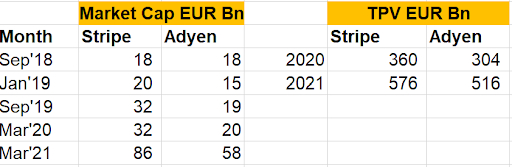

While Adyen does not receive anywhere close to the adulation Silicon Valley darling Stripe gets from the press, this Netherlands-based company processed €516 billion of payments throughout the world last year, a whopping €212 billion more than they processed in 2020.

Over the last month, I spoke with a couple of Adyen shareholders and interacted with several pseudonymous Twitter accounts. I appreciate their help very much. Here’s the outline for this deep dive:

Section 1 - Adyen’s place in the payment complex: I briefly explain the payment value chain and how Adyen fits into this chain.

Section 2 - Adyen’s value proposition and TAM: I discuss how Adyen crossed the early chasm, how it is able to take market share from legacy players, and how I estimated its TAM.

Section 3 - Competitive dynamics against legacy players and fellow disruptors: I dissect competitors in two broad segments—legacy players and fellow disruptors—and then elaborated how Adyen is positioned against them.

Section 4 - Management and capital allocation: I highlight Adyen’s approach to capital allocation and management philosophy of scaling the business.

Section 5 - Valuation and model assumptions: I discuss model/implied expectations.

Section 6 - Final Words: Concluding remarks on Adyen

Section 1: Adyen’s place in the payments complex

Let me first start with some basics of the payment value chain. Even for many seasoned investors, the whole payment value chain can seem quite complicated. Therefore, while I may not be able to elucidate every little detail of the value chain in this deep dive, I want to provide a basic framework of how payments work.

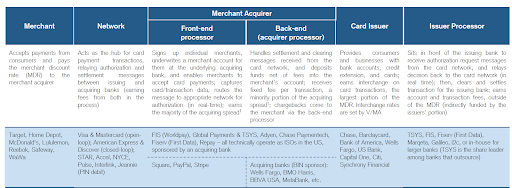

As shown below, in any payment transaction, there are quite a few parties involved: merchants, card networks, merchant acquirers, card issuers, and issuer processors (read the description of these parties if you are not quite familiar).

Source: Credit Suisse Payments Primer (2020)

Let’s start with how a $100 transaction at Target (i.e. the merchant) would work. While it may seem you just pull your credit/debit card out of your pocket at Point of Sale (PoS) and in a few seconds your payment is deemed successful, there is a dizzying amount of work being done in the background in the meantime.

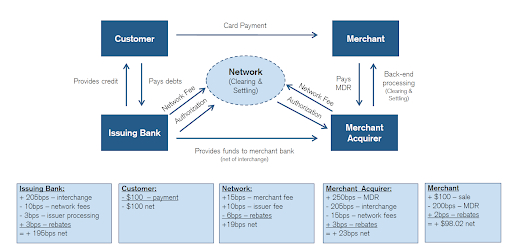

Once you insert the credit card into Target’s PoS, your card credentials and transaction data are captured. Then, the merchant acquirer, such as Adyen, sends the data to the card networks (Visa/Mastercard), who subsequently queries the customer’s issuing bank for authorization (fund availability, fraud checks, risk analysis etc. are also done here). Once green lighted by the issuing bank, the authorization flows through the card networks to the merchant acquirer (e.g. Adyen). The merchant (the retailer) receives confirmation from its merchant acquirer that the transaction is authorized, and then the sale is completed. This is called the authorization phase. Then the settlement phase starts.

To start the payment process, the credit card issuing bank provides credit on behalf of the customer to settle the transaction, which is routed through the card networks, who then passes the transaction to merchant acquirer’s back-end processor for settlement. The back-end merchant processor then settles the net outstanding balance between the card-issuing bank and the merchant-acquiring bank (where the merchant has its merchant account). The merchant bank will then credit the merchant’s account for the amount of the purchase, less fees charged (i.e. Merchant Discount Rate or MDR) for facilitating the transaction across multiple parties.

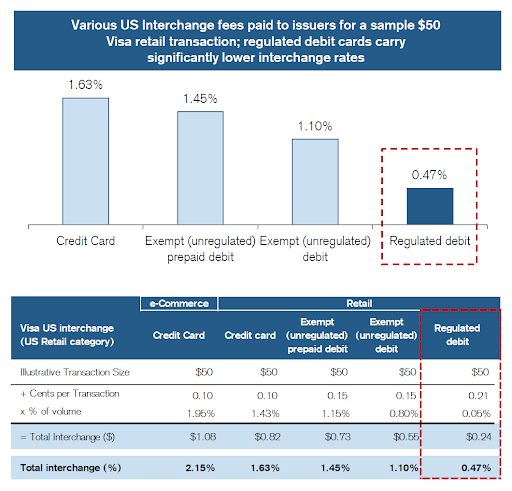

These fees can be segmented in three ways: a) interchange fees, which can range from ~150-300 basis points (bps), paid to the issuing bank, b) acquiring spread, which can vary from 10-100 bps, paid to the merchant acquirer, such as Adyen. If the front-end processor is separate from the back-end, the front-end processor gets the majority of this spread, and c) network fees of 15-20 bps goes to Visa/Mastercard (net of rebates and incentives).

When the customer receives the credit card statement, he/she either pays the bill in the full amount, or can choose to pay interest on unpaid balance. The issuing bank receives the interest in that case.

For the more visually inclined, you can see the following diagram to understand the flow of information in the payment value chain (the diagram shows a transaction in PoS terminal):

Source: Credit Suisse Payments Primer (2020)

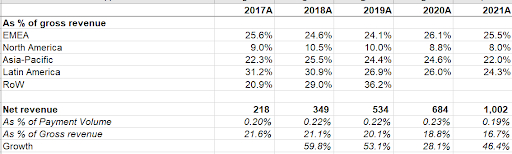

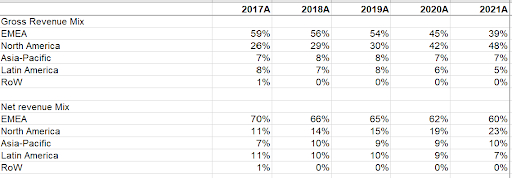

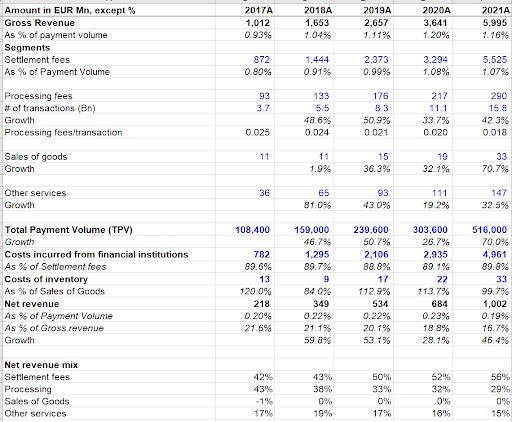

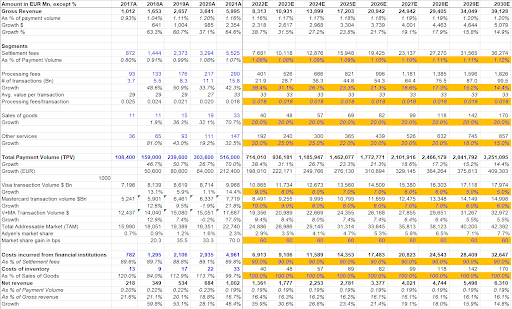

Adyen’s gross revenue is segmented in four categories: settlement fees, processing fees, sales of goods, and other services. Settlement fees is more than 90% of gross revenue (and ~56% net revenue); while processing fees is ~5% of gross revenue, it is ~29% net revenue.

For the settlement fees, Adyen follows a “interchange plus” pricing. Adyen has a transparent pricing model and charges fees to merchants based on its own incurred costs, plus a mark-up for its acquiring services as agreed between each merchant and Adyen. On average, Adyen’s take rate is ~10% of the settlement fees. Acquiring spread, or mark-up, is inversely related to merchant size, since higher volumes give larger merchants greater negotiating leverage. As we will discuss later, Adyen primarily focuses on enterprise customers who are generally considered large merchants.

Since Adyen follows interchange plus pricing for its acquiring services, its net revenue margin (net revenue/gross revenue) may wildly differ in different geographies. For example, in North America, Adyen’s net revenue margin has been ~8-10% in the last five years, whereas in all other regions around the world, it hovered around ~25-30%. The difference can be almost entirely explained by different regulations around interchange fees in the US vs. other regions in the world.

Note: Adyen used to segment geographical breakdown in five regions, but changed to four regions in 2020

While in Europe interchange fees are capped at ~20 bps for debit and ~30 bps for credit, the range is much wider (~20-110 bps) in the US because of the Durbin Amendment (Dodd-Frank Act of 2010). If the issuing bank has greater than $10 billion in assets, interchange is capped at 21 cents+5 bps of transaction value. However, there is no such cap for issuing banks with less than $10 billion in assets, which is why we see fintechs and neobanks partner with such banks to launch debit cards. Since interchange fees are the cost Adyen pays to the issuing bank and keeps the spread, revenue after interchange fees, or net revenues, is essentially Adyen’s “topline,” and gross revenue is a much less meaningful number to look at.

Source: Credit Suisse Payments Primer (2020)

Because of higher interchange rates in the US, North America has greater contribution to Adyen’s gross revenue mix, but Adyen generated 60% net revenue from Europe and 23% from North America in 2021.

Note: Adyen used to segment geographical breakdown in five regions, but changed to four regions in 2020

For processing fees, merchants pay a fixed fee per transaction (not based on transaction value). The higher the number of transactions, the more money Adyen makes in processing fees. Adyen processed 15.8 billion in transactions last year.

Adyen also has a POS terminal product, which is recorded in the “Sales of Goods” segment. This is mostly sold at cost; therefore its contribution to net revenue is almost zero.

Finally, Adyen has “other services” such as foreign exchange service fees, third-party commission, issuing services, risk, and fraud analytics etc. These value-added services to merchants allow Adyen to expand its take rates.

Since we now have an idea on where Adyen sits in the broader payment value chain and how it makes money, let me explain Adyen’s value proposition, as well as its Total Addressable Market (TAM).

Section 2: Adyen’s value proposition and TAM

After founding Adyen in 2006, Pieter and his co-founders had to deal with the chicken and egg problem in payments. In order to be relevant player for any Payments Service Provider (PSP) in the market, you need payment volume, but since a startup by definition doesn’t get to process a high volume of payments, it is very difficult to be relevant in the early years. It took Adyen five years before they finally got their first sizable merchant: Groupon. Then many other US based companies started using Adyen to process their international payments. The US market, however, was difficult to crack even though Adyen tried to make a mark in this market from the very beginning; it took Adyen more than 10 years to become a major domestic player in the US.

Why was Adyen able to cross the early chasm?

Adyen primarily targeted internet-scaled businesses with global ambitions. Generally speaking, most startups first target SMBs or some niche to build their reputation over time, so that they can eventually move up-market. Adyen took the opposite approach; the founding team had a very clear-eyed vision in terms of the problems large merchants face in payments, and how they could build one single platform to address such core and crucial needs. In many cases, many of these internet-scaled businesses have country-specific contracts with their PSPs, and hence when they would expand their operations to other countries, they could give their PSP mandate to a new company. For example, when Spotify or Uber expanded their operations in Australia, they could choose Adyen to process their payments in Australia. Over time, if Adyen outperforms in authorization rates or other performance metrics, Uber/Spotify would have a very compelling reasons to consider Adyen to process their payments in other regions as well.

Once they crossed the early chasm, Adyen was able to rapidly grow in three ways:

- Adyen’s customers themselves grew fast in the last decade or so. As the Ubers and Spotifys of the world created new markets for their services, Adyen was there to process their payments. Adyen grew exponentially because its customers themselves were conquering the world.

- Adyen followed a “land and expand” model with many merchants. If a merchant started using Adyen to process e-commerce transactions, over time the same merchant may have ended up also using Adyen’s PoS services. Adyen’s “unified commerce” blurred the need for different service providers for different channels as they became one-stop solution for all channels.

- Finally, Adyen’s share of transaction volume with its existing merchants itself increased over time. Most merchants have contracts with multiple PSPs. Over time, they can track relevant metrics, such as authorization rates, and objectively decide to give more volume to the PSP that has performed better.

Adyen mentioned more than 80% of their growth last year came from existing merchants. More importantly, volume churn has consistently remained at less than 1% in Adyen’s history. Of course, Adyen also added new merchants to their platform to grow their payment volume and net revenues. Even though Adyen had significant customer concentration in initial years, the merchant base is growing increasingly diversified over time.

Source: Adyen’s public filings

Why was Adyen able to outcompete the incumbent PSPs?

Unlike legacy incumbents, Adyen has a single integrated platform that operates across the entire value chain and offers simplicity for merchants by eliminating the need to work with a disparate group of gateways, risk management providers, processors, and acquirers. Adyen explained in its prospectus when it became a public company in 2018:

“The typical payments landscape has been characterized by a fragmented patchwork of providers and legacy systems, which Adyen believes leads to an inferior shopper experience, both explained and unexplained declined authorizations, low conversion rates and a high number of fraudulent transactions leading to administrative costs for merchants. In this context, the Adyen team set out to fundamentally change the payments industry by building a single, fully-integrated global platform which seeks to provide a high quality level of service to merchants.”

Adyen’s platform runs on open-source technology and is independent of software commercially licensed from third parties. This is a conscious decision by Adyen, and this philosophy almost permeates every decision it takes. The whole platform was built in-house and, unlike other payment/fintech companies, Adyen seems to have strong aversion to acquiring companies, as they believe patching together disparate platforms can dilute their value proposition of being a single platform. Adyen grew their business entirely in an organic way. Adyen also thinks that “managing all operations in-house helps to maintain a high level of security and performance. The end-to-end control further enables flexibility for Adyen to combine platform components in different configurations to meet the various needs of its merchants and allow for scalability.”

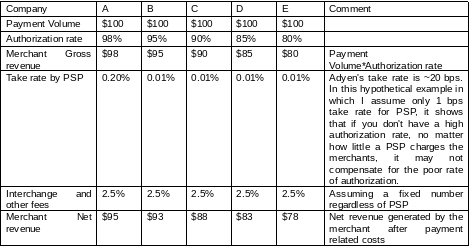

Because of the holistic view Adyen has thanks to its single integrated platform, it can provide insights into why a specific transaction is rejected by an issuer and find ways to improve authorization rates. Adyen’s focus was not on building the most cost competitive product in the market, but on building a single platform that would improve authorization rate and hence increase merchants’ revenue. If Adyen’s platform can increase authorization rate from 90% to 95%, the net revenue contribution is much larger than what a merchant might be able to save by picking the most cost competitive PSP out there. Even for MBI Deep Dives, I probably lose ~1% of my subscribers every month just due to payment failure (some of which do come back to re-subscribe/update payment information later). The prospect of higher authorization rate is much more compelling for larger merchants than choosing the lowest cost alternative. In the “Business Breakdown” episode, Michael Willar from Stenham Asset Management mentioned ~20% of all online transactions are declined (vs 5% in offline/card-present payments); therefore, there is certainly appetite for PSPs who can enhance authorization rates to boost merchants’ revenue. To drive this point home, please see the below example to understand why higher authorization rates (and not lower take rates) are more compelling from the merchants’ perspective:

Local acquiring licenses also helped Adyen in increasing authorization rates. Adyen explained, “Acquiring licenses allow Adyen to process payments domestically in all key markets, generally leading to higher authorization performance and lower processing costs. Additionally, local acquiring licenses can lead to faster merchant payouts. Lastly, local acquiring generally results in lower interchange costs and card network fees, which directly benefits the merchant in Adyen's transparent "cost-plus" pricing model."

Adyen used two types of acquiring: a) “full acquiring license,” in which Adyen performs the full acquiring process and takes full financial responsibility for chargebacks where the merchant is unable to pay, and b) “Bin sponsor license,” in which Adyen is unable to obtain a direct license from the card networks and instead 'rents' the license held by a local acquiring bank by paying a fee to the local acquiring bank. Adyen still controls the full technical stack for payment processing and takes full financial responsibility for chargebacks where the merchant is unable to pay. Because of this credit risk, Adyen is very careful in choosing industries/merchants they take the responsibility of acquiring. Merchants also demand a strong balance sheet to feel comfortable. For example, Adyen doesn’t do acquiring in the airlines industry. At the time of IPO, Adyen had full acquiring license in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Last year, Adyen also received US branch license which allows them to do full acquiring in the US. It is estimated that full acquiring may save 1-3 bps. Given the size and volume of the payments market, every bps matters for both merchants and Adyen.

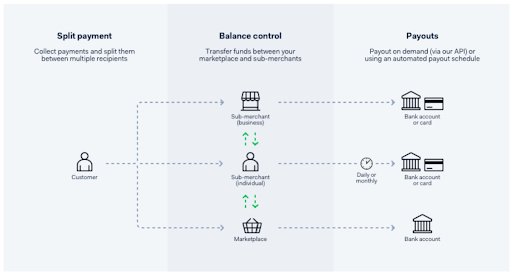

Apart from settlement and processing services, Adyen has additional products and services. One of them is Adyen Checkout, which can be used for online, mobile, and in-store payments. Adyen has also been focusing heavily on their “Adyen for Platforms” product (formerly known as Adyen MarketPay), which is an end-to-end payment solution for peer-to-peer marketplaces, on-demand services, crowdfunding platforms, and any other platform business models. McKinsey’s “2021 Global Payments Report” projected that marketplaces may enjoy 50-75% market share of digital commerce by 2025. Given the dominance of the marketplace business model, it is very intuitive that payments services for marketplace businesses attracted a lot of attention from Adyen. Marketplaces have unique challenges in payments, since they are responsible not only for integrating payments into their platform, but also for facilitating payouts of funds to their sub-merchants. Therefore, marketplaces have a much higher regulatory burden for things such as KYC and on-boarding requirements for a large number of sub-merchants.

“Adyen for Marketplace” is “an extension of the same full payments stack as the Adyen platform, and includes automated and secured onboarding of sub-merchants, the ability to automatically split payments between merchant funds and sub-merchant payouts, optimized payout facilitation, and managed compliance.”

Products such as “Adyen for marketplace” also introduce opportunities for new products down the line. One such product that Adyen is currently working on is “Capital," which would enable them to help these marketplaces provide financing to the sellers. I am not sure about how the economics will be shared between Adyen, the marketplace, and other relevant parties in this chain.

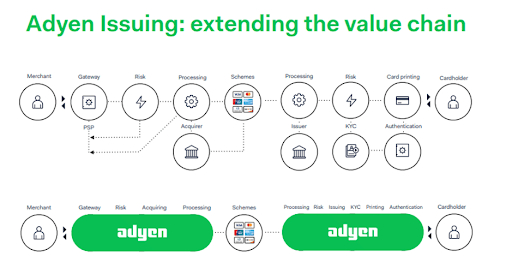

Apart from Capital, another product Adyen mentioned that may have “meaningful standalone net revenue contribution in the long term” is “Issuing,” which allows its merchants to build their card programs and create customizable virtual and physical cards from V/MA, among other things. Adyen’s issuing product is still in the “tens of millions” vs. acquiring volume of hundreds of billions.

Finally, Adyen also has several data-enabled products such as RevenueAccelerate, RevenueProtect, Shopper Insights etc. Revenues from these ancillary products are likely to be extremely high-margin business.

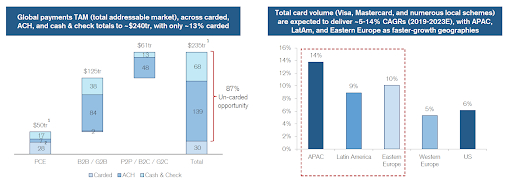

Adyen’s TAM: Payments is exceptionally large market. In fact, global payments volume was estimated to be $240 trillion, which was higher than global GDP of $85 trillion in 2019 because multiple payments are made for the same level of output. However, since Adyen does not process payments in China, we need to consider payments volume ex-China.

Source: Credit Suisse Payments Primer (2020)

Although I am not aware of reliable estimates for global payment volume ex-China over the years (there might be some behind paywall), I decided to go for a reasonable alternative.

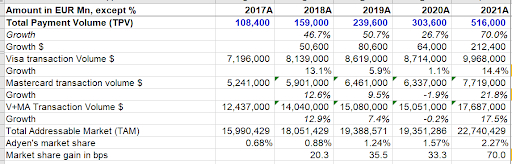

Both Visa and Mastercard publish their payments volume consistently, and given they have ~75% market share of digital payments volume in the US, adding Visa and Mastercard’s global payment volume and then dividing it by 75% would give us a rough estimate of the TAM and how it’s growing. Since their market share obviously varies from country to country, and their combined market share is likely to be less than it is in the US, I decided to divide it by 70% to estimate Adyen's relevant TAM. Of course, this is far from perfect, since Visa/Mastercard’s combined market share may also be increasing and a more correct approach would be to divide their payment volume by their market share in each year instead of dividing it by a constant 70%. Since that’s no easy task to figure out, I decided to do it in this simple framework, which I believe to be not materially off the mark.

Once we have the TAM, we can also calculate Adyen’s penetration in the TAM. Please note that since Visa and Mastercard report payment volume in USD, whereas Adyen’s numbers are in EUR, I have converted the USD numbers to EUR. As per my estimates, Adyen’s penetration was ~70 bps in 2017. But they have continued to gain market share every year and currently have ~2.3% penetration. Please note this is a very broadly defined TAM and since Adyen does not focus on the SMB space, its penetration of its actual addressable market is likely to be higher. Nonetheless, the broader inference does not change much, even after considering such nuance, and Adyen is likely to continue to grow its payment volume at a rapid pace.

Section 3: Competitive dynamics against legacy and fellow disruptors

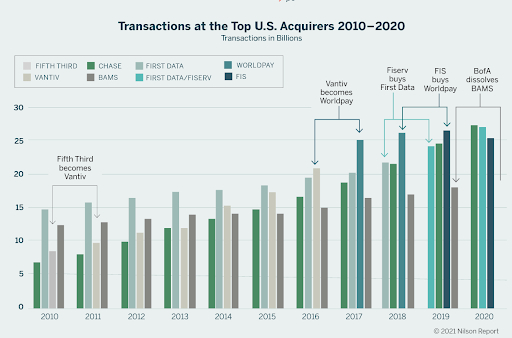

Broadly speaking, there are two sets of competitors for Adyen: legacy players and fellow disruptors. I will discuss these two broad groups separately. But before I get into that discussion, please note there has been a dizzying amount of M&A activity in this industry over the last decade.

Legacy players

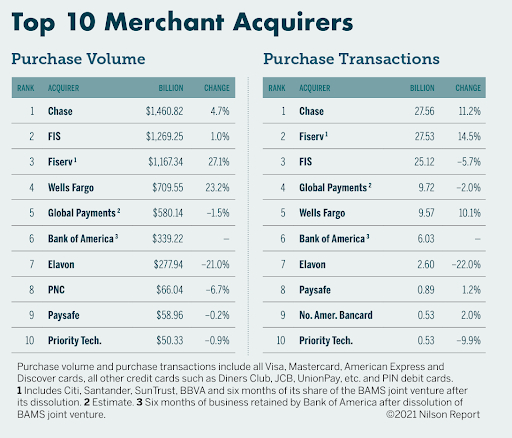

The three largest legacy players in this space are Chase Paymentech (owned by JPMorgan), Worldpay (owned by FIS), and First Data (owned by Fiserv). Each of these players processed more than a trillion dollars of payment volume in 2020 and collectively did ~$4 trillion.

One of the advantages for Chase Paymentech is its competitive pricing given JPM’s scale, as well as their ability to bundle with other payments and banking products/services. Moreover, Chase Paymentech tends to enjoy higher authorization rates for its own issued cards. This is likely to be true for other banks as well; Bank of America’s (BofA) payment business is likely to deliver a higher authorization rate for BofA-issued cards. Card issuance is somewhat concentrated in the US, as the top 5 players have ~60% market share, led by Chase. The more market share Chase has in card issuance, the more likely it is they will have a stronghold in the payments service business given their higher authorization rate in their own cards. Therefore, while Chase may perform worse than Adyen when it comes to transactions in other banks’ issued cards, it can remain a fiercely competitive player in this space for years in the future. However, apart from lower authorization rates in other bank issued cards, Chase seems to be more sluggish in responding to the ever-evolving and increasingly complex payments world, partly because of the multiple platforms, companies, and integrations that are required, and the technical debt that results over the years. For example, RH switched from Chase to Adyen in 2018, since Chase wasn’t able to handle split payments (e.g. charging customer half of the fees upfront and the rest upon delivery).

FIS and Fiserv, the second and third largest players respectively, likely have even more acute technical debt. Adyen’s current management themselves sold their prior company Bibit to RBS and RBS’ payment business, which included Bibit, was spun out during the global financial crisis to a private equity firm. Worldpay eventually became public in 2015, but then got acquired by Vantiv in 2017. Finally, Vantiv itself was acquired by FIS in 2019.

Michael Willar elaborated on the point of technical debt of legacy players in the “Business Breakdown” episode:

“If I just pick on Worldpay, they are almost an amalgamation of 18 to 20 different platforms and even more systems that have been literally glued together. And the analogy that I can give you is actually from a startup called Silverflow, which I have recently been speaking to, and they were started by ex Adyen employees. Super switched-on guys. Maybe there'll be a different podcast one day about them, but the analogy that they said, it's like gluing together different car parts from different manufacturers to make one car. You might get from point A to B, but you're bound to have a lot of issues and high maintenance costs. If it breaks down, you might not be able to find the spare parts. This is not great for a merchant for a number of reasons.

The first is that when these platforms were built, they were both in the eighties and nineties and technology was just completely different. Memory, processing power, even bandwidth was extremely expensive. And these legacy platforms were built on mainframes to be economical and use only the bare minimum of the data in a transaction given the high costs. If you fast forward today, everything that was expensive is not so expensive and the big D word in data is just mission critical to merchants. Because they want to improve the customer experience. They want to generate loyalty. They want to improve rates of fraud. They want to lower their costs. Just a plethora of reasons. A lot of the merchants that have switched to Adyen have said this to me, that having access to this data is just a total game changer. Then if you think about stitching up these multiple different old platforms, it creates a lot of headaches and costs.

If you are a global company and you are selling to 50 different markets, you don't want to be dealing with 30 different platforms. It's totally different companies, almost, with different operation teams you have to separately integrate for every single market in different channel. And this often leads to higher costs, low authorization rates, makes you slower to innovate and just complicates reconciliation. So this in essence is the key difference between Adyen and the legacy processes. Again, if you listen to what merchants say that have dealt with both Adyen and the legacy players, they will tell you how bad it is. So with Adyen, again, you deal with one platform, one contract for every merchant, every channel with transparent pricing, you get access to data, and again, higher chance of better authorization rates.”

Overall, it appears to be extremely likely that legacy players will share donors in this space over the next decade. But it is also important to note that legacy players are unlikely to go extinct either. As mentioned earlier, authorization rate can be pretty high for some of the legacy players for their own issued cards. Moreover, merchants almost always (although there can be exceptions) want to have contracts with multiple PSPs to have negotiating leverage. In most cases, merchants use one of the PSPs as their primary processor, whereas the other players are their fallback options. In this industry, the larger the merchant is, the lower the take rate a PSP enjoys for a couple of reasons:

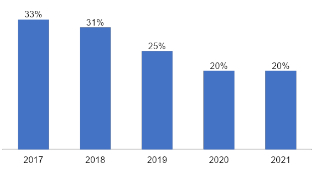

- Larger merchants enjoy volume discounts. For example, in 2017 Adyen’s top 10 customers contributed 33% of net revenue, even though the same customers generated 39% of processed volumes. Similarly, the top 120 customers contributed 69% of net revenue but 83% of processed volume in 2017. While Adyen still discloses top 10 customers contribution to net revenue (20% in 2021), it does not report their contribution to processed volume. But it is easy to infer based on past disclosure that larger merchants are likely to enjoy volume discounts. Because of the significance of processing volume for PSPs for technological, branding, and frankly perhaps valuation implications, some PSPs may even agree to process payments volume at abnormally low pricing. I have heard speculation that Stripe processes Shopify’s payments at very, very low take rates. Adyen is allegedly much stricter in pricing and generally known as the “premium” PSP in the industry. Therefore, merchants using Adyen perhaps willingly choose them over other alternatives because of the potential of higher authorization rates. Because of the multiple PSPs that most merchants choose, there is not much of a switching cost. Given their “premium” nature and lack of much of a switching cost, it is absolutely essential for Adyen to maintain the quality of their product and services. Considering how mission-critical payments is for any business and the failure rate of transactions especially online, despite the negotiating leverage large merchants are very much willing to focus on increasing authorization rates rather than saving a few bps.

- The other reason PSPs enjoy lower take rates from larger merchants is that many large merchants do a lot of data analytics and add-on services in-house rather than taking those services from Adyen or other PSPs. For example, although Uber uses Adyen (along with a few others) to process payments in many parts of the world, it does not use reporting, reconciliation, analytics and fraud tools from providers, as they do this in-house. Some Adyen shareholders I spoke with mentioned that when a merchant is interested in the full range of analytics and services, their choice of primary PSP leans more towards Adyen.

Given the three largest legacy players in aggregate still process ~8x the volume Adyen did in 2021, legacy players remain the primary competition for Adyen today and perhaps in the near to medium term. Adyen was able to take quite a few marquee merchants from some of these legacy players over the last few years. For example, these are some of the companies on which Adyen became the primary PSP over the last 5-7 years (the parentheses show the earlier primary PSP for these merchants; in many cases they are kept as fallback to primary PSP): Canada Goose (Chase), Etsy (Worldpay), Uber (Worldpay), Farfetch (Worldpay), eBay (Braintree/PayPal).

Even though legacy players remain the primary competition, there are some fellow disruptors who can also be a headache for Adyen over the long-term.

Fellow disruptors

The two companies that can be labelled as “fellow disruptors” who are also taking share from legacy players are Stripe and Checkout. Let’s start with Stripe.

Stripe is perhaps Silicon Valley’s favorite private company. The Collison brothers have so far raised $2.2 billion from VCs, and the company was valued at $95 billion in its latest funding round. In contrast, Adyen raised just $266 Mn in its history, and when it came to public market, it didn’t even raise money from the market. While there is not as much detailed disclosure available since Stripe is a private company, their recent “2021 Business Update” shared some important data points. Stripe disclosed they processed $640 Bn payments in 2021 which increased by 60% YoY. To make it more apple-to-apple comparison, I have converted the dollar amount to EUR (Adyen’s reporting currency). I have also shown below Stripe and Adyen’s valuation each time Stripe raised money from VCs over the last three years (Again, Stripe’s numbers were converted to EUR). Since Adyen has been a publicly traded company, its numbers are derived from its stock price. As you can see below, while four years ago, Stripe and Adyen had similar valuation, Stripe’s valuation was almost 50% higher than Adyen’s in March 2021. Please note Adyen’s market cap peaked at EUR 84 billion in November 2021. It is currently valued EUR 45 billion. I have read reports that indicate Fidelity recently marked down Stripe’s valuation by 23% from the March ’21 numbers. If we assume such mark as current valuation, Stripe remains worth ~50% more than Adyen, even though Stripe’s reported total payment volume (TPV) is only ~10% higher than Adyen’s.

What could be potential reasons for such valuation discrepancy? One potential reason could be that Stripe’s take rate is likely to be higher since they have much more focus and exposure to SMBs, which may allow them to enjoy higher take rates. Moreover, Stripe has built incredible developer affinity over the years; Stripe talks about supporting startups from the first lines of code through IPO and beyond. Stripe mentioned in its 2021 Business Update that 60% of the tech companies that went public in 2021 were Stripe’s customers. As explained earlier, it may be difficult to infer much from the statement; any merchant can choose “Stripe” or “Adyen” (and a few others) to process their payments, but the much more important information that’s missing here is whether Stripe is their primary PSP (Stripe probably is, but we don’t know for sure). Moreover, even if Stripe’s take rates is higher from SMB or startups, Shopify’s payment volume itself was ~13% of Stripe’s TPV (assuming 100% Shopify’s payment processed by Stripe) from which Stripe’s take rate is likely to be anemic.

Of course, even if take rates are higher for Stripe, we don’t know whether margins are similar to Adyen’s. Adyen posted ~63% EBITDA margin and ~73% incremental EBITDA margin in 2021 which is exceptionally high bar for Stripe to match. In fact, as part of Adyen’s due diligence process, I spoke with an investor who has a good idea about Stripe’s numbers. Since the information is not public, I cannot mention these in my deep dive; however, I can only mention that Stripe’s margin numbers I heard are no where close to Adyen’s numbers.

Perhaps Stripe just enjoys a massive narrative premium in its valuation compared to Adyen. I found it interesting that despite being a private company, there are perhaps more deep dives available on the internet on Stripe than there are on Adyen! Of course, it’s very much possible price discovery is simply weak in the private market these days.

As alluded to earlier, the payments market is such a large market that it may not have to be either Stripe OR Adyen debate, especially given both companies can take share from legacy players over time, and their combined payments volume is only ~25% of the largest three legacy players’ volume today. Both companies can potentially be big winners (given their valuation, they are already somewhat priced as big winners, so this isn’t a valuation comment rather a “business” comment). However, they are increasingly likely to be each other’s major competitors in the long-term.

Although Stripe focuses on startups, their Business Update makes it abundantly clear that they are also pretty serious about enterprise and international merchants, both of which are Adyen’s strongholds. Unfortunately, we don’t have enough details/data points to make a fair assessment and comparison of these two companies unless Stripe becomes public.

Checkout: Checkout is another private PSP that has garnered a lot of attention in recent times. Guillaume Pousaz, the founder and CEO of Checkout, bootstrapped the business for the first seven years before raising $1.8 Bn in just the last three years. Pousaz mentioned on a podcast (April, 2021) that they never spent a single dollar on sales or marketing before raising $230 million in Series A; it was purely word-of-mouth and product-led growth. He also mentioned the cash he raised from VCs wasn't spent; it just sits on the balance sheet as they maintain their capital discipline. While PSPs can be pretty capital-efficient businesses, they all pale in comparison with Adyen’s track record of utilizing just $266 million of external funding to create ~$50 billion worth of market cap. Based on the latest round in January this year, Checkout is currently “valued” (perhaps a word very loosely used here) at ~$40 billion which is just ~20% below the current market cap of Adyen (but was ~45% below Adyen’s market cap when the round was announced). In the funding press coverage at TechCrunch, the article mentioned that “The company processed hundreds of billions of dollars in payments in 2021 alone." Given the valuation, I assumed Checkout must have processed at least $200-300 billion of payments volume in 2021. Since this is a private company, we cannot be sure, but my channel checks tell me the actual number is very close to $100 billion, which admittedly shocked me. While I cannot be certain of the veracity of the data, I am merely mentioning the data point I have heard from some investors during my due diligence. For what it’s worth, the growth rate for payment volume is likely to be faster than Adyen and Stripe.

However, similar to Stripe, some caveats apply here as well. Checkout’s take rate is likely to be materially higher than Adyen’s. While Adyen does not exhibit much of an interest in crypto, Checkout is very much leaning to crypto. The same TechCrunch article mentioned Checkout “powers some of the payments features of several cryptocurrency companies, such as Coinbase, Crypto.com, FTX, MoonPay and Novi from Meta.” Again, my channel checks tell me crypto contributes a material amount of processing volume to Checkout, and hence the take rate is likely to be considerably higher than Adyen’s. However, EBITDA margins were nowhere close to the same universe as Adyen’s (my understanding based on conversations with investors). Given the current market environment, if Checkout were publicly traded, I think it’s not unfair to say it would probably trade at a fraction of its last funding round valuation.

An article published in December 2020 indicated that 50% of Checkout’s transactions happened in Europe, with much of the rest coming from Middle East (the CEO’s family lives in Dubai) and Asia. Unlike Adyen, Checkout doesn’t have a PoS product, which makes it difficult for them to get any retailer with physical locations. While they are yet to be a relevant player in the US, Checkout does have an ambition to grow its presence in North America.

Even though Adyen, Stripe, and Checkout can be bucketed as “fellow disruptors”, they did take different approaches to get where they are today in terms of strategy and management philosophy, which I’ll elaborate in the next section.

Section 4: Management and Capital Allocation

As mentioned earlier, Adyen has not done any acquisitions in its history. On the other hand, Stripe has done 13 acquisitions since inception, and Checkout has acquired four companies in the last two years alone. Adyen believes in organic growth. The core problem they have identified for legacy players is the maze of inevitable platform integrations-related challenges that arise from acquisitions over the years. The root of this rigid philosophy of no M&A was eloquently explained by Pieter on a podcast:

“With the first company, you build something, see it run successfully, you sell it, you celebrate it. After selling Bibit, I stayed in the company for another two years, and as a result I had to run it under the umbrella of a larger company that made all sorts of decisions that I wouldn't personally make.

So when you start again with another company, you are very keen on not selling it. This implies that the decisions you take should be very different. Building something to keep is like restoring a car. If you restore a car to sell it, the paint has to be great and the motor has to be running. But if you think you're going to do 200,000 miles yourself and you know you have a ton of problems hidden in the car, you will eventually encounter them yourself.

Similarly with Adyen, all the problems we have ever had in the business model, we encountered them ourselves at some point. So we really make sure we don’t have any problems with the business model because in seven years from today, we will still be running this company.”

Given how tempting it must be to just acquire a few companies here and there to increase take rates or expand geographical footprint, it is quite admirable how religiously committed Adyen has been with organic growth so far. There is no indication that they have any appetite for M&A going forward.

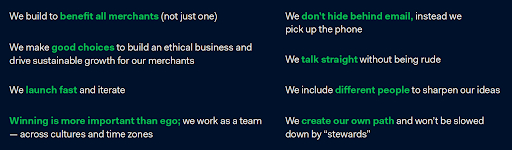

Interestingly, one of the complaints about Adyen that I came across is that they don’t do as many customizations for merchants, which is a key value proposition for Checkout. Adyen is unwilling to undertake customization efforts for on a merchant-by-merchant basis because it violates “The Adyen Formula”, as shown below. Like Amazon’s principles, these are not just feel-good words, but rather a code of belief that gets embedded deep into Adyen’s culture. The very first formula states that “We build to benefit all merchant (not just one)." Adyen organizes its projects around cross-functional teams, called "streams," which are comprised of employees from the business side and the development side of the company and built in collaboration with merchants. Each stream follows four-weekly release schedule.

Source: “The Adyen Formula” from 2021 Annual Report

Adyen guides to maintain ~5% of net revenue as capex. So, if Adyen doesn’t do M&A, is not highly capex-intensive, and generates mid-40s FCF margin, it must be buying back shares and/or paying dividends, right? No. Adyen has not paid any dividends or bought back shares. Management explained in one of their earnings calls why that is the case:

“…we have a dividend policy where we do not pay out any dividends, and we continue to have this policy given the high growth of the company.

And then the second question is like at what stage this dividend policy will be reevaluated.

We will continuously look at this. As long as we are in this high-growth trajectory, we will keep this dividend policy. So I can't give a precise timing on it right now. But as we're still in high-growth mode, it's not expected to change on the short term.”

Management reiterated the no-dividend policy in a recent call and elaborated why they prefer to have more cash on the balance sheet:

“We still have a strategy to keep this cash on the balance sheet basically for two reasons. It makes our discussions with regulators way easier, because they can see that we're a very financially stable company, which I think is important if you're applying for licenses throughout the world. So that's the first reason.

The second reason is that we're winning larger deals with larger companies as a customer. And also there, having this stable balance sheet without any debt is helping us. So at the moment, we don't have a strategy to change this, so we will continue the current no dividend policy for now.”

So, if a payments company generates gobs of free cash flow (FCF), does not pay dividend “for now” but also doesn’t repurchase shares or, the existing shareholders must be getting diluted via share based compensation (SBC) at a pretty high rate, right? No.

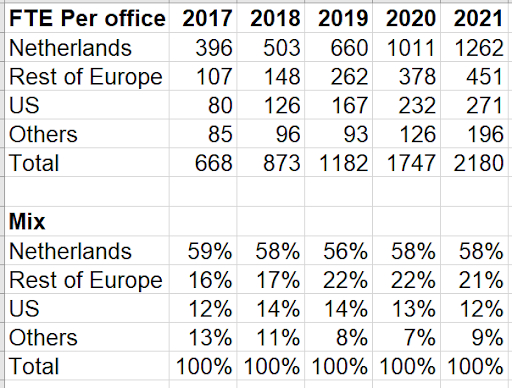

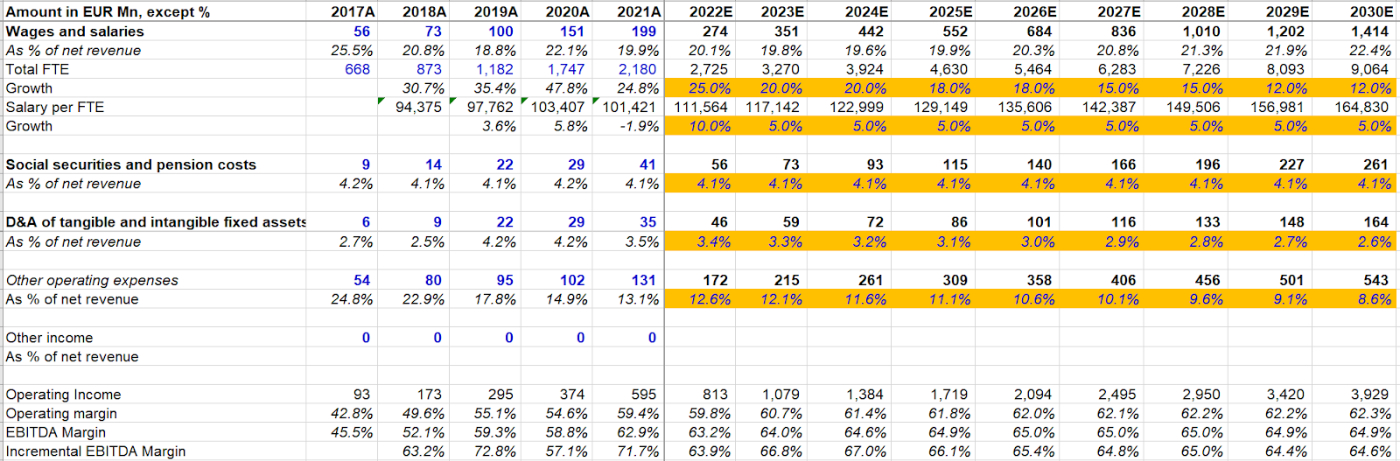

In 2021, Adyen spent just ~$6 million in SBC, which is only ~60 bps as a percentage of their net revenue. Last year, Adyen only spent ~20% of their net revenue in wages and salaries of ALL employees, which is typically just one of three divisions' (R&D, S&M, and G&A) salary in most of tech companies at similar topline these days. Since Adyen had 2,180 full-time employees (FTE), this implies an average Adyen employee made EUR 101,421 in 2021 which is perilously close to “low income limits” in San Francisco. I am not joking; US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defined $82,200 for an individual and $117,400 for a family of four in San Francisco to be low income limits in 2018.

Given the abundance of SBC that I’m used to seeing in many of the tech companies I have covered before, I had to triple check the numbers as I was quite incredulous looking at Adyen’s SBC! It turns out lack of SBC (and dilution) and the resultant sky-high margin is one of the key reasons investors adore Adyen. But why has Adyen managed to keep SBC so low and how sustainable is it really?

After speaking with several investors and doing my own due diligence, there are three reasons I could identify to explain such low SBC at a time when engineers’ compensation has skyrocketed:

1.A recurring and admittedly unsatisfying explanation that I have heard is that since Adyen is a Dutch company and the Dutch are relatively more frugal and conservative (I understand the broad-brush biases this may imply which is why I already mentioned it to be unsatisfying), Adyen hasn’t indulged in the “bubble” of engineering compensation at Silicon Valley. Even if that’s true, the question remains why (and if) Adyen was (and will be) able to attract good talent.

2.A far more cogent explanation is Dutch regulations. In Netherlands, the variable part of compensation i.e. your bonus cannot exceed 20% of fixed compensation. In the rest of EU, the regulation allows variable compensation to be maximum 100%. I am not aware of any such regulation in the US. As a result, there is potentially a massive talent arbitrage that exists in the other side of the Atlantic. Adyen took full advantage of such arbitrage.

Since almost ~60% of Adyen’s employees are from the Netherlands, the regulatory talent arbitrage helps Adyen to keep its salary expenses low. Interestingly, even though North America contributed to 23% of Adyen’s net revenue last year, only 12% of its employees are in the US.

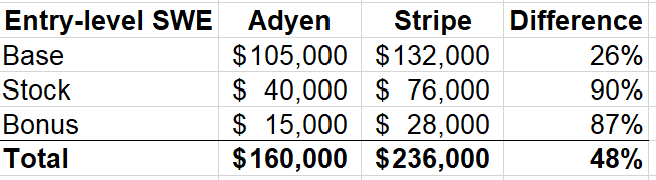

Having said that, even in the US, Adyen lags behind their peers considerably in terms of compensation. I have compared Stripe and Adyen’s salaries in levels.fyi and found ~50% differential between Stripe’s and Adyen’s offer for an entry-level software engineer (SWE). Please note I have looked at Adyen’s offer for a SWE in the US to make it a more apples-to-apples comparison with Stripe, since salaries in the Netherlands are materially lower partly because of the aforementioned regulation. When I went through posts in Blind, a forum where people anonymously share their thoughts on the companies they work for, a recurring complaint from employees at Adyen is Adyen’s below-average compensation. Perhaps there is indeed some truth to “Dutch frugality and conservatism."

Source: levels.fyi

3. Finally, some Adyen shareholders think Adyen was able to keep the compensation in check because of its unique culture. Pieter spoke about Adyen’s hiring process on this podcast, in which he mentioned that during the hiring process, every single employee at Adyen is interviewed by one of the six management board members (recently Adyen spoke about extending this group to 12 people to help them scale) to ensure the quality of human resources remains high. Please note Adyen has a two-tier board structure consisting of a management board (6 members) and supervisory board (5 members) who are independent of each other. The company speaks about great work-life balance and a no-nonsense work culture that they believe attracts pretty competent talent.

Here's the concern I have. When I think about durability of Adyen’s competitive advantage, a large part of it relies on their ability to maintain and grow the technical superiority of the platform. If they consistently lose out on hiring talent because they are paying ~50% lower than some of their peers, I wonder whether Adyen’s platform will remain cutting-edge 10 years from now. While some Adyen shareholders admit that talent retention is indeed a concern they deeply think about, one investor thought the very premise of my question/concern is flawed. He believes that engineering talent is bit of a commodity, and that the relationship between compensation and quality is not quite linear. More importantly, a lot depends on a company’s ability to extract value out of their talent regardless of the compensation. It is not obvious to this investor why Stripe’s quality of talent is inherently better than Adyen’s just because Stripe pays 50% higher. I see some merits on these push backs, and I think one might argue that given that Stripe’s (or other peers’) stock is a sizable part of total compensation which faced (or is likely to face) a severe haircut, the actual compensation difference may not be 50% anymore. Moreover, the companies with heavy SBC component in comp may have to deal with employee discontent themselves, as employees grapple with a total compensation noticeable lower than what they presumed. The fact that Adyen was able to withstand not to indulge into the “hyperinflation” of engineering compensation in the last few years perhaps speaks volumes to their commitment to build culture without relying too much on higher pay. It may not be easy to build a great company just by paying people more.

As mentioned earlier, I have read through common complaints about Adyen’s compensation on Blind. When I spoke with an Adyen shareholder, I also came to know that the shareholder spoke with a recruiter who’s been recruiting for Adyen for quite some time and has noticed material spike in attrition recently. When asked for the reason for attrition, the shareholder mentioned he spoke with former employees and they sometimes mentioned that the joy of working for a startup understandably gets diluted over time as the company gets bigger and bigger. These are, of course, anecdotal data points, and the whole tech industry itself experienced retention issues in the last couple of years, so it can be difficult to infer much from such anecdotes. Adyen was asked about talent management in a recent earnings call (February 09, 2022) and the management basically said attrition rates are similar to prior years:

“If you look at our attrition rates over the two pandemic years, they are similar to the years before. So you also see that we have a very loyal group of employees that like working here. So it's something that we are very protective of.

At the same time, we also expanded where we are with our engineering team. So we added Madrid and Chicago there to be closer to where the merchants are but also not to be just dependent on Amsterdam. So that's how we look at the strategy there.”

Despite the above discussion, I am reluctant to assume Adyen can keep paying a noticeably below market-level salary forever; at the very least the growth rate of wages and salaries per headcount is likely to be faster than their peers. I understand the investors’ current angst between the lopsided value shared between employees and shareholders in many tech companies today, but generating 60% EBITDA margin and 70% incremental EBITDA margin while paying noticeably below average market salary doesn’t appear to be good equilibrium between labor and capital either.

Section 5: Valuation and model assumptions

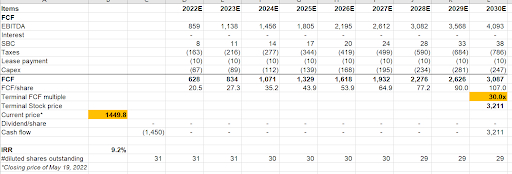

If you are reading my deep dives for the first time, I strongly encourage you to read my piece on “approach to valuation”. Please read it at least once so that you understand what I am trying to do here. I follow an “expectations investing,” or reverse DCF, approach as I try to figure out what I need to assume to generate a decent internal rate of return (IRR) from an investment, which in this case is ~9%. Then I glance through the model and ask myself how comfortable I am with these assumptions. As always, I encourage you to download the model and build your own narrative and forecast as you see fit to come to your own conclusion. None of us have the crystal ball to forecast 5-10 years down the line, but it’s always helpful to figure out what we need to assume to generate a decent return.

Revenue Model: As explained in section 1, Adyen’s revenue can be segregated in four categories: settlement fees, processing fees, sales of goods, and other services.

Settlement fees are driven by total payment volume (TPV); gross settlement fees are ~110 bps of TPV, and after paying 90% of gross settlement fees to financial institutions mostly for interchange fees, Adyen keeps the rest 10%. As explained in section 3, TAM for TPV is calculated based on sum of Visa and Mastercard’s transaction volume, dividing it by 70%, and finally converting into EUR (Adyen’s reporting currency) by multiplying it by 0.9. Since Visa and Mastercard report these numbers regularly, it will be easier to track and maintain this model going forward. For projections, I have assumed Visa and Mastercard will grow their transaction volumes by high single digits in the next five years, and then gradually reach mid-single digit growth by the end of this decade. I have assumed Adyen’s market share in this TAM will increase by 60 bps each year going forward. Historically, they gained 30-35 bps market share in 2019-2020, but really accelerated in 2021. It remains to be seen whether this acceleration is likely to sustain. Legacy players have a stronger presence in the physical world, so as the world is opening up post-Covid, it may be difficult to keep last year’s incredible growth momentum in TPV. Based on my assumptions, Adyen is expected to process EUR 3.2 trillion payments volume in 2030 which implies ~8% market share for Adyen. This doesn’t seem implausible, given that I expect Adyen to continue to take market share from legacy players due to its superior platform and/or legacy players’ growing challenges in staying relevant in the increasingly complex payments environment. Can Adyen get to 10% share? That's the vexing questions that can be hard to answer. However, if you see TPV growth in absolute EUR, Adyen will have to grow EUR 400 billion year-over-year in 2030. These are some lofty assumptions, although not quite improbable considering the size of the payments market. I want to follow and observe Adyen more before being comfortable with such assumptions.

Processing fees are based on number of transactions; the higher the number of transaction, the higher Adyen’s processing fees. Overall, Adyen’s take rate or net revenue as % of TPV is ~20 bps. I have wondered how sustainable this take rate is. There are two competing point of views at play here. On the one hand, the 20 bps take rate does not incorporate any future revenue streams such as issuing, capital, or any other products Adyen may launch going forward. On the other hand, I wonder whether the competitive dynamic that lets Stripe process Shopify’s payments at a very low take rate will be more common in the future. Of course, the merchants know how exorbitantly profitable these PSPs are, and merchants also know they have good enough alternatives. Unlike Visa and Mastercard, consumers have no real connection with Adyen or Stripe; a retailer not accepting Visa or Mastercard is a real hassle for the consumers but Adyen or Stripe is largely abstracted from the consumers. A compelling counterargument is, of course, that payments is deeply mission critical and as explained earlier, saving a few bps is not worth it at the expense of higher authorization rates. The more I have thought about it, I have come to the conclusion that if we ever reach a point where two or three PSPs reach statistically similar authorization rates, there could be tremendous pricing pressure on the PSPs. Looking through that lens, it made me appreciate Adyen’s religious commitment to one platform and focus on scalability and higher authorization rates rather than customization. Unfortunately, none of the companies in this space report their global authorization rates, which would allow us to compare and contrast how things are progressing in this industry. It appears to be a critical data point that investors don’t have access to.

Overall, my model implies net revenue CAGR of 31.0%, 27.5%, and 22.7% respectively for the next 3, 5, and 9 years. Adyen guides net revenue CAGR between the mid-20s and low-30s in the “medium” term (Adyen doesn’t define “medium” term).

Cost structure: Below the net revenue line, the major component of Adyen’s cost structure is wages and salaries which was ~20% of Adyen’s net revenue last year. While Adyen had only 2,180 full-time employees in 2021, Stripe reported more than 7,000 employees in its “2021 Business Update (LinkedIn shows 7,574 Stripe employees and 1,802 Checkout employees as of this writing). I assume Adyen’s hiring spree will continue going forward and projected a 5% increase in salary expense per FTE in 2023-2030. Based on these assumptions, Adyen will have ~9k FTE in 2030, a number Stripe will probably hit in less than couple of years. Salary per FTE can prove to be a bit lower, since Adyen is expanding in the US and even though they pay lower compared to their peers in the US, it costs 30-50% more even for Adyen to hire engineers in the US compared to engineers in Amsterdam. Overall, my model does not imply much of an operating leverage even though Adyen mentions “We aim to improve EBITDA margin, and expect this margin to benefit from our operational leverage going forward and increase to levels above 65% in the long-term.”

As per my model, EBITDA margin remains around ~65% going forward.

Valuation: To generate ~9% IRR, I had to use 30x FCF multiple in 2030. Please note I have ignored working capital dynamics in FCF calculation because cash receivable from merchants, and payables to merchants drive working capital which need to be ignored as cash coming from those dynamics are not unencumbered. Moreover, even though Adyen does not appear to be willing to pay dividend or buyback shares “for now," I have assumed 50% of FCF each year will be deployed to buy back shares. Adyen intends to beef up its cash position to provide ample comfort to regulators and merchants; I don’t know how they will quantify ample reserve to feel comfortable, or at what point Adyen may think about paying dividends or buying back shares. If Adyen does not use FCF to pay dividend or buyback shares for a long time from now (assuming incredibly low probability for M&A), the IRR assumptions may turn out to be a bit aggressive.

Section 6: Final words

While Adyen stock is down ~45% from its peak, I still think the current valuation may prove to be a bit rich. Of course, stock and business can be very different things. As per the model, Adyen’s revenue and EBITDA are assumed to be ~6-7x in 2030 from its 2021 level, and yet during the same time the stock may do a ~2x from the current price, even if these numbers prove to be true unless you assume a pretty elevated terminal value multiple. Having said that, there are certainly ways Adyen can prove my model to be “conservative” if its market share gain in global, ex-China payment volume accelerates and its new products such as issuing, capital etc. end up contributing material amounts to the top and bottom line. I will keep a close eye on market share gain and take rates to re-asses my opinion going forward.

If someone forwarded this piece to you, please consider subscribing to MBI Deep Dives. Your support is deeply appreciated. Thank you so much.

Recommended content

- Credit Suisse Payments Primer is available on the internet here

- The Scale Lab episode with Pieter van der Does

- Business Breakdown episode on Adyen

- Wharton Fintech Podcast episode with Kamran Zaki, Adyen’s COO

- 20 VC episode with Guillaume Pousaz, Checkout’s Founder and CEO

- Brosef’s substack pieces on Adyen vs Checkout and Adyen’s valuation

- In Practise interview of former VP of Adyen discussing how Adyen enters new markets

Disclaimer: All posts from “MBI Deep Dives” are for informational purposes only. This is NOT a recommendation to buy or sell the securities discussed. Please do your own work before investing your money.

Abdullah Al-Rezwan, who writes under the pseudonym "Mostly Borrowed Ideas" (MBI) on Twitter, runs MBI Deep Dives, where he publishes one deep dive every month. You can explore sample deep dives on Uber, Etsy, Lululemon, and Roku on his website. To subscribe to his work directly, go here.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!