Hey! Today we're introducing a new column at Every: No Small Plans by Casey Rosengren. It will be published bi-monthly and explore what it means to play bigger in life and work.

Casey is a founder and executive coach based in New York who's written for Every about living by your values, peer coaching, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Weaving in research from psychology, philosophy, and organizational behavior, he'll explore what it means to do work that matters and live well in the face of mortality.

If you want to make sure you get Casey's writing going forward, hit follow:

“Everyone, get back in the building. NOW!”

It was early 2021, and my partner and I were visiting my sister in Hawaii. We’d spent the afternoon having coffee at one of the fancy hotels that dot Oahu’s shoreline, enjoying the beautiful views of the ocean.

Just as we were about to leave, an officer in full SWAT gear ushered us from our car and back into the lobby.

The police didn’t tell us much about what was going on, just that there were reports of an active shooter somewhere on the premises. For the next several hours, nearly 100 of us sheltered in place in the hotel lobby.

We would find out later that we were lucky—the shooter had barricaded himself in his room, and we were never in any imminent danger. But for those first few hours, we had no idea what we were dealing with or how perilous the situation was.

Existential psychologist Irv Yalom writes that brushes with death can be clarifying, pointing toward one’s unlived life—the life we’d be living if we were honest with ourselves about what was important to us and had the courage to align our lives with that desire.

My experience that night was no exception. Reflecting that night, I felt generally good about my work, and I was grateful for my friends, family, and my partner. However, at the prospect of an untimely death, there was one place where I felt like I had unfinished business.

I wanted to write.

I’d written in fits and starts since 2020, but as life got busy and other projects took precedence, writing had fallen to the wayside.

Things didn’t change immediately; it took many months for me to fully commit to making writing a consistent part of my life. But my experience that night stayed in the back of my mind, and eventually, I made writing a priority.

How can we awaken to our unlived life outside of a near-death experience or major crisis?

One way to do this is the tombstone exercise from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

The exercise involves writing your epitaph, which is an inscription written on a tombstone summarizing what your life and behavior has been about. In this exercise, we explore both an ideal epitaph and a feared epitaph.

The ideal epitaph represents your values, encapsulating the kind of person you want to be and the life you’d like to have lived, looking back from your deathbed.

The feared epitaph is an epitaph written as if you died today, summarizing what your life and behavior has been about. As such, it can be a powerful way to shed light on your unlived life—the gap between your values and how you’re currently living.

This exercise is most powerful when you engage with the fact that you will die someday, and genuinely ask yourself how you might want others to remember you and what you were about.

To get a sense for how it works, let’s explore an example of how I’ve used it in my own life.

A real-world example

A few years ago, I was going through a career transition, trying to decide what I wanted the next phase of my life and work to be about. To get some space to explore the decision, I signed up for a self-guided retreat at a monastery in upstate New York.

I had hoped that taking some time offline in a beautiful location would help bring clarity to my question, but my first few days on retreat were actually quite stressful.

I was trying very hard to figure out what I should do next with my life—journaling, reading, and thinking through each option over and over in my head. I wasn’t enjoying my time away, and I wasn’t making any progress on my decision.

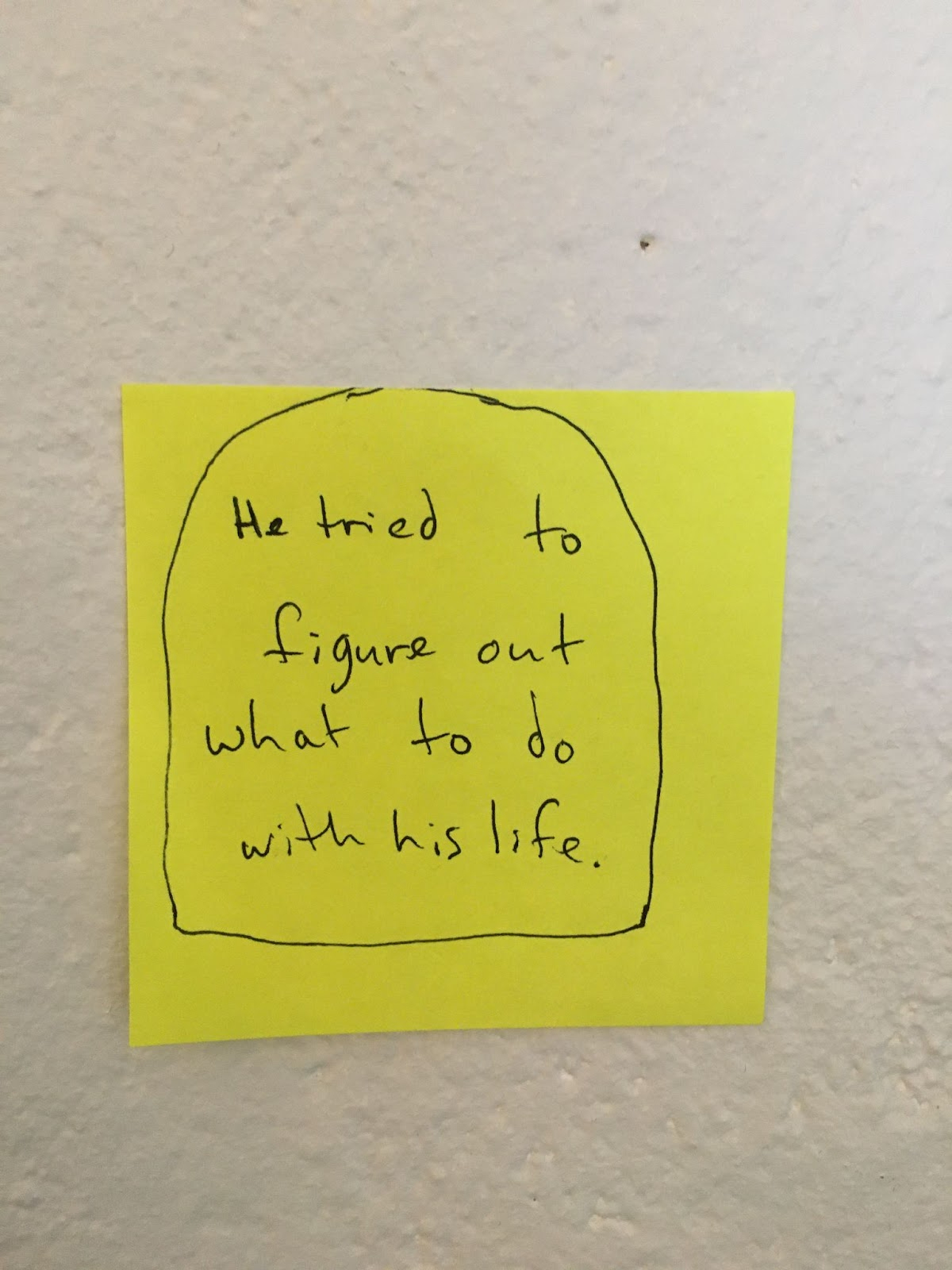

So I decided to do a tombstone exercise, starting with a feared epitaph. This is what I wrote on a post-it on my wall:

“Here lies Casey. He tried to figure out what to do with his life.”

(The actual Post-it note hanging on the monastery wall.)While the above example is a bit absurd—my life is obviously more nuanced than that—writing this feared epitaph helped me recognize how narrow my life and behavior had become.

Everything I was doing on retreat was about trying to figure it out. When put in the context of mortality, I realized that I didn’t want to spend my moments so fixated on trying to resolve the uncertainty I was feeling.

I wanted to think intentionally about the future, but in a way that allowed me to enjoy the present, knowing that answers often come in their own time.

So I wrote an ideal epitaph—one representing how I wanted to show up to the rest of my retreat.

I didn’t take a photo of this one, but it was something like:

“Here lies Casey. He thought intentionally about what he wanted in life, and still lived his moments fully, with love, play, and irreverence.”

For the rest of the retreat, I tried to notice when my behavior had fallen back into trying to figure it out, and to instead see if I could allow the uncertainty to be there and still show up fully to the natural beauty all around me.

Since the retreat, I’ve made this an ongoing practice. Whenever I’m sitting with a big decision and notice that I’m fixating on trying to find an answer, I think back to these epitaphs and remember what is meaningful for me about how I want to show up to uncertainty in my life.

Writing your feared epitaph

When trying this exercise for yourself, you can start with either the ideal or feared epitaph. I like to start with the feared epitaph when working with clients.

Again, your feared epitaph represents how it might read if you died today—what your life and behavior is currently about.

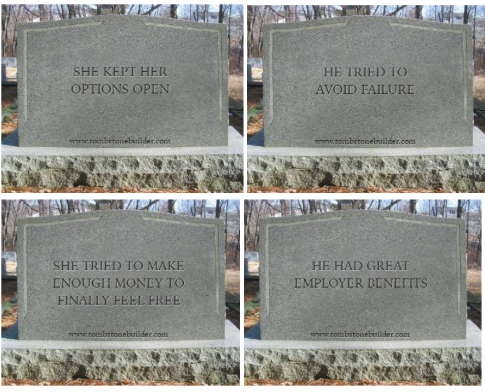

Here are some examples of feared epitaphs I’ve seen (edited onto actual tombstones):

To come up with your feared epitaph, you might ask:- What is my life and behavior about in this moment?

- What in my life am I seeking to avoid or manage?

- What small victories am I currently chasing?

- If I keep living how I’m currently living, what am I most afraid my tombstone might say?

You could choose to make this about your life more generally, or you could focus on a specific domain in your life, like work, health, or relationships.

Once you’ve written your feared epitaph, the next step is to write your ideal epitaph.

Writing your ideal epitaph

Writing your ideal epitaph can be a challenging task. How can a person sum up in a sentence or two what they truly want their life to be about?

One way to make this feel less daunting is to narrow the scope of your epitaph to a specific situation or life domain. This is what I did in my personal example above, reflecting on what I wanted to be about on retreat and in my relationship to uncertainty.

The epitaph I wrote—"He thought intentionally about what he wanted in life, and still lived his moments fully, with love, play, and irreverence"—represents an ideal around how I wanted to show up in this area of life.

You could write an ideal epitaph for almost any life domain or situation—be it health, family, relationships, work, spirituality, education, friendship, or whatever feels meaningful to you.

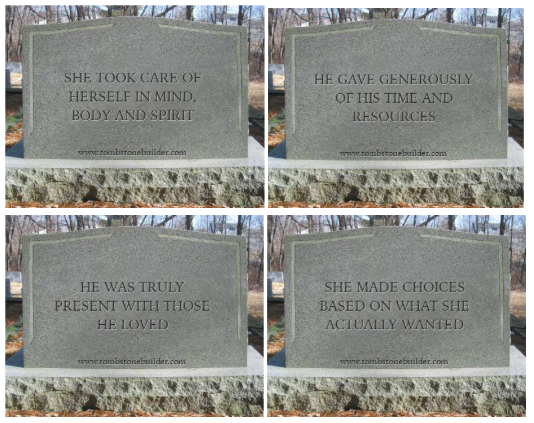

Here are some examples (again edited onto tombstones):

If you’d like to take a stab at a more general epitaph, rather than a scoped one, it can be helpful to hold whatever you come up with loosely and know that it will likely change over time.

I’ve found that my ideal epitaph often changes in response to what I’m working on and what I care most about in each season of life. Here are some general ideal epitaphs that I’ve written at different points in my life:

- He was present to his life and those he loved.

- He helped people drop the struggle with their inner experience and show up more fully to their lives.

- He walked with love and courage into the great unknown.

- He helped people connect with something larger than themselves and their problems.

Our ideal epitaphs aren’t meant to be written in stone (no pun intended). As the Zen saying goes, these are meant to be “fingers pointing at the moon,” inviting us to connect with an experiential sense of what a meaningful life might look like for each of us. The specific words don’t really matter—it’s the underlying meaning they point to that is important.

We don’t have to get it perfect, and we don’t want these to become new rules that we use to analyze our lives. If an epitaph starts to feel like an intellectual rule or a rigid standard, it may be time to let it go and start exploring new words that feel more alive to you.

Zooming out—to zoom in

Our behavior is always motivated by something, though we may not always be aware of what we’re moving toward or away from. The tombstone exercise is powerful because it sheds light on what our actions are ultimately in service of (i.e., trying to figure it out vs. living fully).

When we become aware of what our actions are about, we’re more likely to notice when our behavior isn’t in service of what really matters to us, and can choose to realign our behavior with our values.

Whether you’re new to values work or you often reflect on meaning, this is an exercise that you can come back to again and again as you move through your life. We all slip into reactivity at times, and this exercise can be a reminder of what we ultimately want our lives to be about.

If you’d like to make your epitaphs even more impactful, you might choose to hang them on the wall as an ongoing reminder of what matters to you. You could also share them with someone close to you, inviting that person to help keep you honest around how you’re doing at living out your values (and deepening your connection with that person in the process).

Reflecting on death isn’t a panacea. When we’re really stuck in unhelpful patterns of behavior, it can take consistent work over time to make real change.

Still, whatever the struggle might be, zooming the lens out and putting our challenges in the context of mortality—and what we truly want our lives to be about—can bring much-needed perspective to a difficult situation.

Casey is offering an eight-week experiential intensive course, Mindful Values, that goes deeper into values work from an ACT perspective. To learn more about the course, check out the home page above or sign up for a free intro sessions. The course starts on Feb. 21. If you’d like to learn more about ACT and values-oriented coaching, drop Casey a note.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!