Sponsored By: Sanebox

Today's essay is brought to you by SaneBox, the AI email assistant that helps you focus on crucial messages, saving you 3-4 hours every week. Sign up today and save $25 on any subscription.

We all make decisions in life that trade-off between what we do for money and how we’d spend our time if money was no object.

Even those who make a living doing something they delight in still have to contend with the money problem. For example, Lionel Messi gets paid to play the game he loves, and also spends time doing this:

The New Messi Chicken SandwichIs Lionel Messi passionate about chicken? Or American chain restaurants? I’d guess not. But even while earning over $100 million per year in compensation playing for FC Barcelona, Messi decided it was worth his time to ink a five-year deal with Hard Rock Cafe.

This may be a solid financial decision—athletes have a limited time window in which they’re a hot commodity, after which their earning power drastically drops. However, with career earnings of over $1 billion, I wonder how Messi will look back on this from his deathbed.

How much is a year of Messi’s life worth?

How about a year of yours?

This has been the core question I’ve sat with for the last decade—how to balance money and meaning on the entrepreneurial path. And there are three archetypal ways that I’ve seen people approach the question:

- The deferred life plan

- Being bivocational

- Choosing to integrate

I’ve had a front row seat to success and failure on each of these paths: I’ve pursued each of these strategies at various times and have helped hundreds of founders grapple with these questions in the communities I’ve built and in my individual coaching practice.

So how does one choose which approach to take?

In this piece, we’ll explore what each of these strategies look like when done well versus done poorly, and how you can approach the question with more intention to decide how you truly want to spend your days.

Imagine having an AI assistant sort your inbox for optimum productivity. That's SaneBox - it filters emails using smart algorithms, helping you tackle crucial messages first. Say goodbye to distractions with features like auto-reply tracking, one-click unsubscribing, and do-not-disturb mode.

SaneBox works seamlessly across devices and clients, maintaining privacy by only reading headers. Experience the true work-life balance as SaneBox users save an average of 3-4 hours weekly. Elevate your email game with SaneBox's secure and high-performing solution - perfect for Office 365, Google, and Apple Mail users. Sign up today and save $25 on any subscription.

The deferred life plan

The term “deferred life plan” was coined by the venture capitalist Randy Komisar in his book, The Monk and the Riddle. It is the choice to do something lucrative now, so you can make enough money to eventually do what you really want.

Sam Altman put it this way in a recent episode of the Y Combinator podcast:

“It’s saying some version of this sentence: My life's work is to build rockets, so I'm going to make $100 million in the next 3-4 years… with my crypto hedge fund, because I don't want to think about the money problem anymore. And then I'm gonna build rockets.”

One example of this strategy working is my friend Blake, who was an early engineer at a number of Silicon Valley startups in the 2010s. He joined each company on its way to unicorn status, and after a decade of developer salaries and two IPOs, he was able to retire in his early 30s. Now, he gets to work on whatever he wants.

But you don’t have to work in tech for this strategy to work. Another friend of mine, Douglas, was able to retire in his early forties on a salary of $36,000 per year. He lived frugally, invested well, and now spends his days writing, thinking, and working as a spiritual director.

When the deferred life plan works, it tends to be because:

- You place high-probability bets on income.

- You live frugally relative to your income.

- You enjoy your day-to-day work enough that you don’t mind doing it for a decade or more.

The most common pitfall on the deferred life plan is lifestyle creep. When you make more money, you acquire more expensive tastes, and your costs rise to meet your new level of income. This is why one third of Americans making $250,000 per year still live paycheck to paycheck.

Problems also arise when you pursue risky paths to income. When startups become your deferred life plan, you can invest years of your life into projects that never pay off. If short-term cash is your primary motivation, FAANGs and Wall Street are often a better path. Indeed, I know several founders who have transitioned into finance after a decade in startups without an exit.

Another challenge of the deferred life plan is that, even when you do reach your desired level of wealth, work may have been so all-consuming that you’ve forgotten who you are outside of it. As Randy Komisar wrote for Harvard Business Week:

“The lucky winners may… find themselves aimless, directionless. Either they never knew what they "really" wanted to do or they've spent so much time in the first step (making money) and invested so much psychic capital that they're completely lost without it.”

Finally, the biggest potential hazard on the deferred life plan is that you may not have as much time left as you think we do. A friend of a friend was just diagnosed with throat cancer in his early thirties. He’ll likely be dead within the year.

Being bivocational

Whereas the deferred life plan approaches money and meaning sequentially, the bivocational path approaches them in parallel. It is the choice to make income in a way that leaves time to pursue meaning outside of work in the form of art, hobbies, or side projects.

Author and founder Derek Sivers is a proponent of this path, saying that the happiest people he knows are the ones who have day jobs and do their art on the side. As he puts it, “Do something for love and something for money. Don’t try to make one thing satisfy your entire life.”

A prominent example of this strategy is Elizabeth Gilbert, who worked as a waitress through her first three novels and only started writing full time after Eat, Pray, Love became a bestseller. She talks more about this choice in her later book, Big Magic:

“To yell at your creativity, saying ‘You must earn money for me!’ is sort of like yelling at a cat; it has no idea what you’re talking about, and all you’re doing is scaring it away…

I held onto my day jobs for so long because I wanted to keep my creativity free and safe… In so doing, I became my own patron.”

This is the promise of the bivocational path—that by making an honest living with part of our time, we can carve out another swath to do the work we really care about.

When the bivocational path goes well, it is usually because:

- You can fully clock out of work at the end of the day

- Your income stream is consistent

- You’re willing to dive fully into your art when opportunity arises

The most common pitfall I see on the bivocational path is when work consumes so much of your time and attention that you don’t have the energy to pursue art in your spare time.

For example, when I started consulting, my intention was to do it part time and spend the rest of the week writing and working on passion projects. However, consulting is feast or famine, so when opportunities came my way, I hopped on them. I ended up taking on so much work that I hired two employees, and all of a sudden I was spending all my time building an agency with no time for the work I’d originally intended to pursue.

This doesn’t mean that consulting can’t work on the bivocational path. It simply means that you have to design your work with this strategy in mind—in my case, selling retainers and simplifying your offering so that you don’t have to spend shower time thinking about client work.

Another pitfall on the bivocational path is when you’re unwilling to take the risk to leap fully into your work when the time comes. The poet David Whyte describes this in one of his books as “rotting on the vine.”

At some point, the bivocational path can become an excuse to underinvest in the work you really want to do out of the fear of what it would take to properly pursue it. For me, this came two years into consulting—I realized I could keep doing fractional growth work for the next 10 years, and it wouldn’t get me to my long-term goals.

When the opportunity presents itself—due to your work getting traction or you saving up enough money to take a sabbatical—you need the courage to throw yourself into the work that truly matters and see where that thread leads in your life.

Choosing to integrate

Integration is about finding a way to monetize what you enjoy doing. It's epitomized by the maxim, "Do what you love and you'll never work a day in your life."

Whereas the other two approaches split money and meaning into different times and projects, integration is about holding that tension more directly and trying to balance money and meaning in the same work.

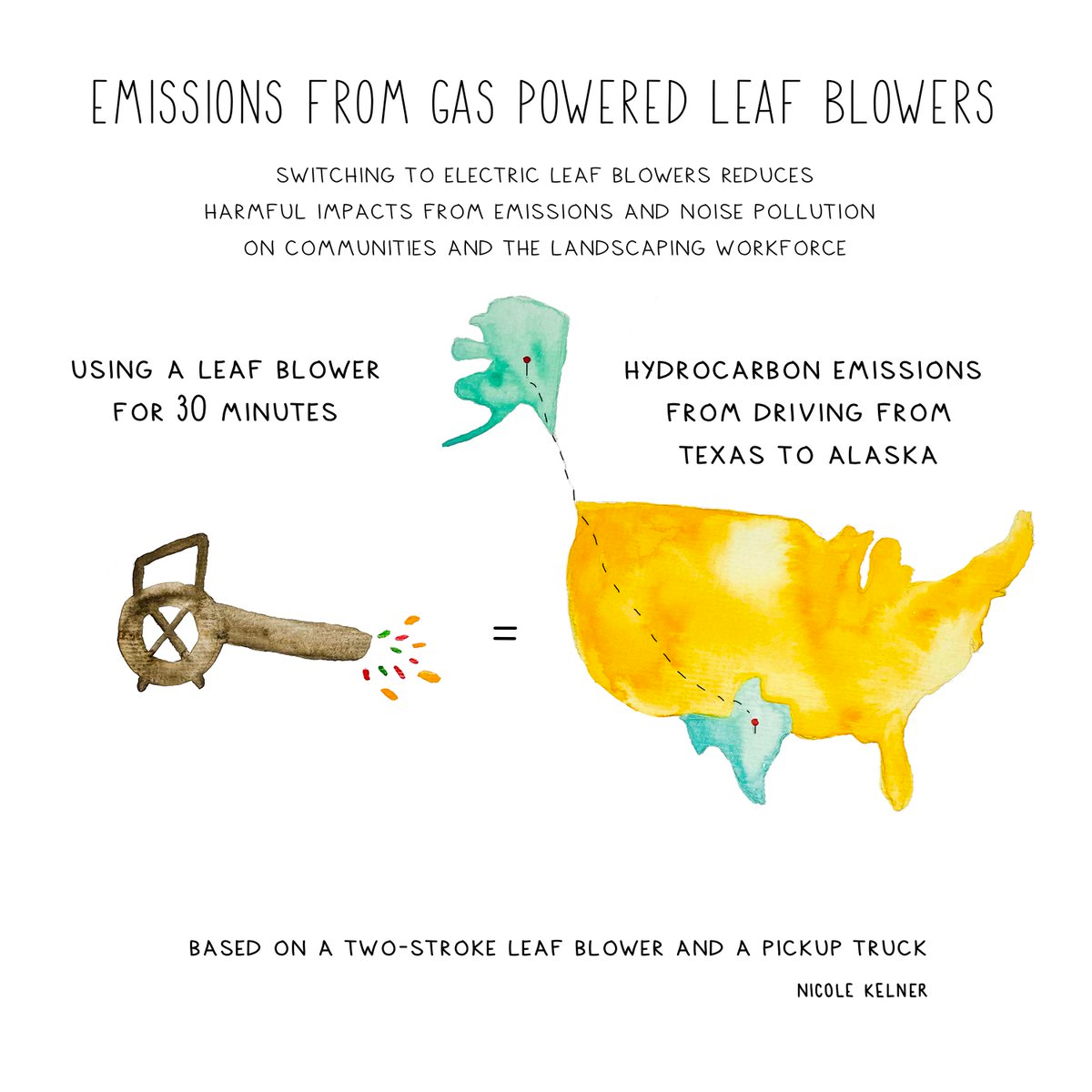

An example of this succeeding is my friend Nicole, who started making watercolor paintings about climate change for fun and sharing on social media. Her work went viral, and after four months, she decided to quit her job and go all in on art. Now, she makes a living through merch and commissioned work.

Here’s one of her more popular posts:

Image credit: Nicole KelnerA startupland example is SafetyWing, a YC company that has raised $50 million to “build a country on the Internet.” Their core business is travel insurance, and its success has allowed the company to invest in moonshot ideas—like creating a borderless passport—that win them press and allow them to attract top talent.

When this strategy works, it’s typically because either:

- The world will compensate you for the work that matters to you (i.e., the therapists I know who see their work as sacred)

- You build two connected streams of work—one that pays the bills, and another that’s pure art

The latter situation is similar to the bivocational approach, except that in integration, your income stream is part of a flywheel that includes your meaning-driven pursuit, instead of being separate. In Nicole’s case, people find her through her art on Twitter and then hire her to do commissioned work.

One common pitfall of the integration approach is what I call the “bakery trap.” It goes like this: someone likes to bake pies, so they decide to open a bakery. A year in, they realize that they’re spending all their time bookkeeping, managing staff, and trying to market the business—and don’t get to spend any time actually baking.

This was what happened to me when running Hacker Paradise. I started the company because I loved to travel and thought traveling for a living would be the greatest thing in the world. Instead, I ended up spending all my time managing logistics and stressing out over cash flow. We spent a month in Barcelona in 2015 and I never once made it to the beach.

Image credit: Benjamin Gremler on UnsplashAnother pitfall is trying to integrate money and meaning too early, before you have a solid grasp on what gives you meaning in your work. When this happens, it’s easy to start optimizing purely for money, like the clients I’ve worked with who have told me some variation of:

“I started ‘X’ business because I was passionate about it. When it didn’t get traction, we pivoted to ‘Y’ and then ‘Z.’ Though it seemed to be working, ‘Z’ was so far away from what originally excited me about the business that I ultimately chose to leave.”

It can be hard to stay connected to your values when money is pulling you in another direction. Like trying to start a fire in a strong wind, you need to protect the early sparks until you have a roaring blaze that’s durable enough to stay aflame despite the wind.

It’s the same with trying to integrate: you need to have a strong connection to what matters to you to be able to stay the course when money and status may pull you in other directions. But if you get it right, the reward is priceless: a life spent doing what you love to do.

Picking an approach

The question of how to balance money and meaning in life is a deeply personal one. There is no one right answer or path to follow. Each approach comes with its benefits, drawbacks, and potential pitfalls.

If what you love doing fits into the structure of a business or startup, then it may be easier to integrate. However, if what you want to do is not as straightforward to monetize—e.g., art, community, or non-profit work—then one of the other approaches may be more effective.

For me, after exiting my last startup, I found that the problem I was most interested in was how to meet our needs for meaning and belonging in an increasingly secular world. I wrote about that for a while and ultimately launched a project in the space.

Because a non-profit seemed like the best structure for the work I was doing, I pursued a bivocational approach. Now, I make my living in a values-aligned way (coaching and writing), while still carving out time to work on projects I care about that don’t generate income.

But that’s my path—and it may not be yours. Whichever approach you choose, it’s important to make the decision intentionally and then pursue it well.

If you’re on the deferred life plan, make high-probability bets on income. If you’re bivocational, make sure you actually carve out time to spend on your art. And if you choose to integrate, try not to lose touch with what matters to you in the face of monetary rewards.

In the end, only you can determine if you’re making this choice with integrity.

Casey Rosengren is a founder and executive coach based in New York. If you’d like to learn more about coaching, drop him a note.

For early access to retreats, workshops, and subscriber-only content, follow him on Every:

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

What’s wrong with Messi’s spending 4 hours (maximum) for a Photoshoot on a branded campaign, for which he will be paid millions? It’s not like he’s advertising tobacco or firearms…

That was a flawed example if ever saw one.

You know how will Messi look back in this deal? He’ll say, “damn they paid me millions for sitting at a restaurant for a few hours, I rock!”

@JCX thanks for commenting George! i don't think the point is necessarily that there's anythign wrong with what messi's doing. more that we all need to make decisions about how we balance our time between purpose and money—and that there are a few common ways to resolve that question.

i don't think Messi will necessarily regret making money on his death bed, but maybe the point is that it's easy to get lost in spending a lot of time making money you don't need instead of focusing on whatever you actually want to be doing. as mentioned in the article, it's not a one-time thing it's a longterm agreement.

either way, i appreciate your comment!

@danshipper and that was precisely my point.

There is a clear subtext in this paragraph, which is apparent to any reader: "Is Lionel Messi passionate about chicken? Or American chain restaurants? I’d guess not. But even while earning over $100 million per year in compensation playing for FC Barcelona, Messi decided it was worth his time to ink a five-year deal with Hard Rock Cafe."

The example actually contradicts the premise; and it comes with a veiled criticism that this individual is spending time doing what he shouldn't.

As he's leveraging his IP, this will be the LEAST amount of time he would put into "working for money". He showed up for a few pics and he will be paid for years — he's detaching time from money. The most commendable of actions to live a life of meaning.

Thank you for having taken the time to respond thoughtfully to my comment, refreshing nowadays.

@JCX this is a great point! well-reasoned thanks George. i appreciate you pointing out the subtext, you're absolutely right.

@JCX -- this is fair, but still a question we all need to answer, i.e. "How much is enough?"

I'm not necessarily saying this is a bad use of time - as I mentioned in the post, athletes may have a time-limited window where they can maximize income, after which their earnings fall off dramatically.

It's more to point toward the question of, "How much is a day / month / year of your time worth?" It may be worth it for Messi to spend a day doing a photoshoot for a few million dollars (if that's what he's being paid), but there is certainly a number at which it doesn't make sense.

There was some calculus he had to make, and we have to make these calculations all the time--though we often do it without any intentionality.

Great read!

I guess the article spikes better when the title is "The 3 ways..." instead of "3 ways...", but I wonder how long till people (always them!) engineer a new way not easily described by any current prototype.

Despite the title, I found the article itself to be a really good prototype for how to give effective advice.

@igorassisbraga - ha yes, would love to see new ways developed! And naming does turn out to be one of the few hard problems in coding / writing...

Thank you for this brilliant piece! I’ve been struggling with exiting a bivocational lifestyle (which I wasn’t even aware that’s what I was doing) to a deferred life plan and it’s been so taxing, frustrating, and even anxiety-stricken. This post helped remind me of how my best path is rooted in two income streams (one career, one money generating passion) and I am so grateful this piece came across my inbox!!! (Thanks to TL:DR newsletter)

@speakerkev - glad this was helpful! Best of luck with the transition!

@speakerkev I'm also subscribed to the TL;DR newsletter, but their crypto one. Which one(s) are you subscribed to, in which this piece showed up (eg.: marketing, startup, other)?