“When I was fundraising for the first time, I had not one but multiple venture capitalists ask me what’s going to happen to my business when death isn’t a problem anymore,” Liz Eddy, the founder and CEO of the end of life planning website Lantern, told me on the phone. I had to laugh.

“There is no signal or sign that there’s going to be any massive or even accessible change to the end of life,” Eddy explained. “Maybe there will be an opportunity for the one percent of the one percent in the future, but if there will ever be an opportunity for the masses is a very different story.”

Eddy was referring to the subset of Silicon Valley elites who moonlight as immortalists. In a piece for The New Yorker, Tad Friend divided these folks into two camps: the “Meat Puppets,” who believe we can hack our biology and stay in our bodies; and the “RoboCops,” who believe we’ll merge with technology in order to live forever. These folks find common ground in pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into anti-aging research, claiming that the purpose of technology is to eliminate mortality, and even creating companies with lofty missions that orbit around the same sentiment: “solve death.”

But with the advent of initiatives that aim to extend life, comes a parallel force; startups rethinking the existing funeral and end-of-life planning industries. If the former group is made up of immortalists, then let’s call the latter group realists.

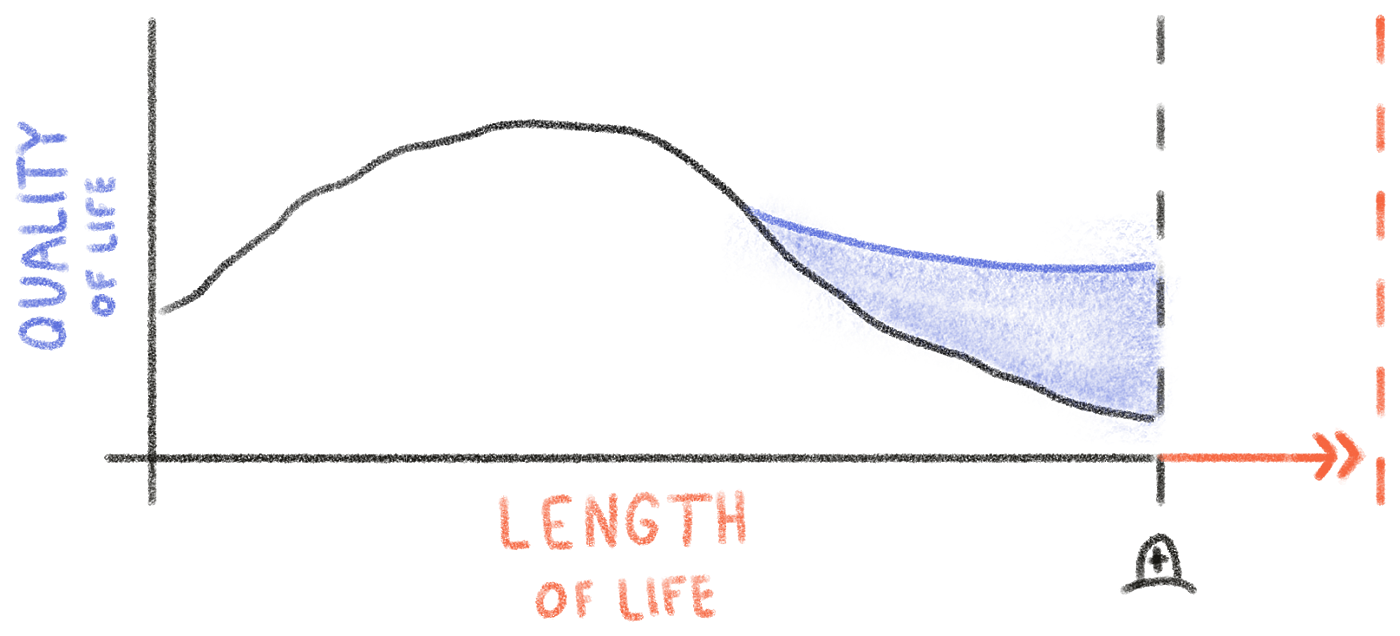

The realists are solving for death in its current iteration; they want to leverage technology to improve the quality of end-of-life care. Realists tend to be more oriented around action versus fascination; they’re talking about death openly, making funeral planning more affordable, and leading online grieving groups. Immortalists err on the side of solving for death due to the frustration that life is too short. They see technology as a means to cheat aging.

Graph: Realists want to move the needle on the y axis, while immortalists focus on extending the x axis.

The notion that death is optional has long been a particular obsession for the ultra-rich, most recently taking hold of those who have made their fortunes from technology. Jeff Bezos put millions into backing solutions to potentially halt, slow or reverse age-related diseases. Ray Kurzweil, an inventor, futurist and Director of Engineering at Google, is a sort of guru for immortalist types, perpetuating the idea that humans will eventually merge with AI to live forever. Peter Thiel’s reported interest in the blood of the young has been written about ad nauseum. Former Coinbase CTO and investor Balaji Srinivasan’s Twitter bio simply reads “it may be possible to reverse aging.”

Honestly, I get it! Not wanting to die isn’t that eccentric — it’s instinctual. The aforementioned cohort spent their careers banking on technology and science as a vehicle to solve the world’s problems — why should they stop at death? If good fortune brings access to the best things that life has to offer, why not continue living?

The immortalist viewpoint inherently lends itself to extreme affluence. The current cost of the idea of life extension is expensive; you can be cryonically preserved for about $80,000 (a whole-body preservation costs $200,000), or for $8,000, you can fill your veins with the blood of young donors. For the vast majority of people, these prices are inaccessible. Immortalist can easily be interchanged with exceptionalist.

It’s worth acknowledging that while life extension may only be accessible to those in the uppermost echelon of wealth at first, it’s assumed that those costs would go down over time and become available to the masses. But, in theory, how long would that take? And are those cost cuts actually inevitable? Not everything adheres to Moore’s law, and it’s plausible that life extension won’t become accessible to everyone anytime soon, if ever.

In a year like 2020, where at least 216,000 more people have died than usual in the U.S., the idea of life extension has been opposed by the severe reality of death. So I’m curious: Who is best equipped to “solve” death, given that — at the time of writing — we’re still all going to die?

More Accessible Deaths

Let’s circle back to the realists. If the immortalist mentality brings resources, prestige and investment to the premise of radical life extension, the realists are solving for death now. This largely entails rethinking the funeral industry, from virtual memorials to diamonds made from cremated ashes to final tweets.

A few decades ago, it was rare for anyone but men to work in the business of funerals; the stereotypical mortician conjures an image of an older man who has been running the family funeral home business for decades. But today, 65 percent of funeral service education students are women and the emerging “death positive” movement is mostly attributed to women who want to break taboos around death planning.

In the startup sphere, end-of-life executives have banded together on a Slack group called “Death & Co.,” which was born out of the frequent communication between founders in this space over the past few years. Today, the group has grown to around 100 people and is open to anyone working on innovating in the end of life field, united around a shared mission to “shift the narrative around death, dying, and grief.” According to multiple members, the group is also made up of about “90 percent women.”

“While the traditional end of life space has been very male dominated, it’s also been about how you can upsell customers and the sales pipeline — the industry was known for that,” said Noha Waibsnaider, founder and CEO of the virtual memorial service GatheringUs. “People dread the process of going to a funeral home and being sold a $10,000 casket.”

Studies have found that the funeral industry is known to use predatory marketing to exploit vulnerable customers who can be hit with cost markups as high as 1000%, a trend that parallels, say, the $200,000 price tag attached to the current process of cryonically preserving oneself. In contrast, founders in the end-of-life industry stressed to me that accessibility and affordability was often their impetus for starting companies in this “unsexy” category and that they’re more focused in taking the upsell out of death.

In the face of a global pandemic, that mission is resonating. GatheringUs’s traffic has increased 140 percent in the last six months. Lantern reported more than a 120 percent increase in users since the beginning of the pandemic. Cake, another end-of-life planning tool, sees about 25 million visitors to its site per year.

“Just in the U.S. alone, there’s normally over 300,000 deaths per month,” Ms. Waibsnaider told me. “In the best case scenario, as fast as I could possibly hire and train people, there’s no way that I could possibly meet that need. There’s so much need and so much room for so many people to start companies in this industry and we still won’t meet the demand. We have a lot of work to do to improve the previously established end-of-life model and it's going to take a lot of players to do it.”

The Last Wellness Frontier

The immortalists and realists share a common goal in that they want to fundamentally alter the way people comprehend death. For immortalists, it will only take one concrete success to shift mindsets around life extension. But since there is currently no proven method of delaying or reversing the aging process, the realists are taking a more incremental approach.

The tack that end-of-life founders are taking by banding together (in places like Slack) is to operate more quickly as a collective. Why? It will be easier to move the needle in establishing cultural norms and customer adoption in viewing a good death as part of a good life.

To that end, end-of-life care companies are often positioned around the “death positive movement.” Death positivity involves talking about death openly, accepting that dying is part of the human experience and celebrating death like we celebrate birth.

In many ways, death positivity parallels the boom we’ve seen in holistic wellness over the past few years, and some end-of-life executives are situating their companies within the larger $4.5 trillion wellness industry. While there is no other industry of its size as heavily predominated by women as the wellness industry, women also make up the bulk of both entrepreneurs and practitioners in end-of-life care.

So what would it look like if we took death wellness as seriously as we take fitness? Or nutrition? Or mental health? At the very least, we might live life more fully. At most, we could start to see death as a celebration, especially as our lifespans are expected to increase over the next few decades.

Personally, I’d rather see the inevitable and impossible path towards death less as something to hack and more as something worth improving. Am I still frustrated that life is too short? Of course! When I contemplate my own mortality, existential panic can take my breath away. But I am more bereaved by the storm of grief — and division of care — that has hung over my family since my grandmother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis ten years ago. Even though my grandmother is still alive, she can’t speak, so I often Google her as a form of coping, searching for anything (anything!) I can learn about her that my family hasn’t already told me. But her life predates the internet, and there’s no sign of an electronic ghost.

Fortunately, Suelin Chen, the founder of Cake, also thinks about this.

“There’s that quote that you die two deaths — when you actually die and the last time someone utters your name,” she told me. “I actually think that we die three deaths: the time when you die, the last time someone utters your name, and the time when the final traces of you are erased from the internet. And that will probably be a really long time for most of us because it’s the internet.”

Perhaps we’re living longer already.

Are There Consequences to Wanting To Live Forever?

Last November, Ambrosia, the young blood transfusion company, went back in business after pausing operations due to an FDA notice warning against such transfusions. Ambrosia’s CEO and founder, Jesse Karmazin, currently has no plans to conduct further studies on the efficacy of his company’s treatments. There’s no proven clinical benefit to infusing blood from young donors to prevent aging, though it could be harmful; an actual consequence in wanting to cure aging.

But for the most part, wanting to slow down aging is harmless. It’s realistic to think that we can push out the inevitable a little bit farther given future life expectancies. But if life extending, or life stopping, technologies do develop at the rate Silicon Valley elites (often men) are betting on, it’s also not difficult to imagine a future where a very small and extremely wealthy group of immortals hold more sway.

We already see this in our notoriously expensive presidential elections; Donald Trump is currently the oldest candidate to assume the presidency and Joe Biden will be the oldest U.S. president in history if he enters office. If you live forever, even if you only work sporadically, money accumulates. Isn’t that why vampires always live in mansions? Death could be the ultimate redistribution of wealth.

If awareness of our own mortality is a driver of civilization, then end-of-life founders (often women) are making an impact while they can. They’re solving for the present, not a utopia. Death is wasteful — it wipes a person’s memories and leaves heartache in its wake. To be sure, it’s a problem worth solving.

Investment Disparities

According to a recent report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, the life extension market (which they dub “techmanity”) is worth around $110 billion today and expected to grow sixfold to $610 billion by 2025. Unity Biotechnology, an anti-aging drug maker backed by Peter Thiel and Jeff Bezos, has raised more than $200 million by itself. In contrast, Crunchbase data estimates that 26 end-of-life care startups have received venture capital over the past three years, collectively raising about $117 million to date.

Perhaps this imbalance in investment is because life extension ventures are tackling the type of ambitious, society-altering challenges that Silicon Valley likes to take big bets on. Perhaps it’s because life extension, and the scientific research it demands, simply requires huge sums of upfront investment. In comparison, the small amount of investment given to end-of-life care companies may be more appropriate, except for the fact that the global death care services market is expected to reach $124.8 billion by 2023.

Does the fact that end-of-life care founders tend to be women have anything to do with this investment disparity? It’s worth calling out that some of the most funded companies in the space — services like Farewill for after death paperwork and Everydays for virtual funerals — were founded by men. Crunchbase’s report also says that funded startups in end-of-life care only offers a limited view of the field, given that many end-of-life-care companies do not appear to be venture-funded.

As venture funding for female founders is notoriously low, and dropping, should we be surprised? No. But perhaps we should take the realists a little more seriously and pause to examine why we historically haven’t. If we’re honest, we might not like what we see.

Taylor Majewski is the founder of Lemon Lab. Previously she was an EIR at Human Ventures, and her writing has been published in the New York Times, Vox, and One Zero.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Solid reading, and a very interesting space to explore.

I think most stay away from the 'end of life' niche because it has such scary connotations. But I fully agree with the author that it needs to be normalised.

If there's some major break-through on the life-extension front I think it would look way more dystopian than people imagine. I can't imagine one scenario where it's not going to turn into a chaotic rush to access the drugs or therapies that make it possible. I will be waiting for the first 'immortal billionaire' to be shot or die in a boat accident for all those forever aspirations to vanish into thin air.

Compared to that, making death and aging more manageable definitely seems like a better scenario and more predictable investment.