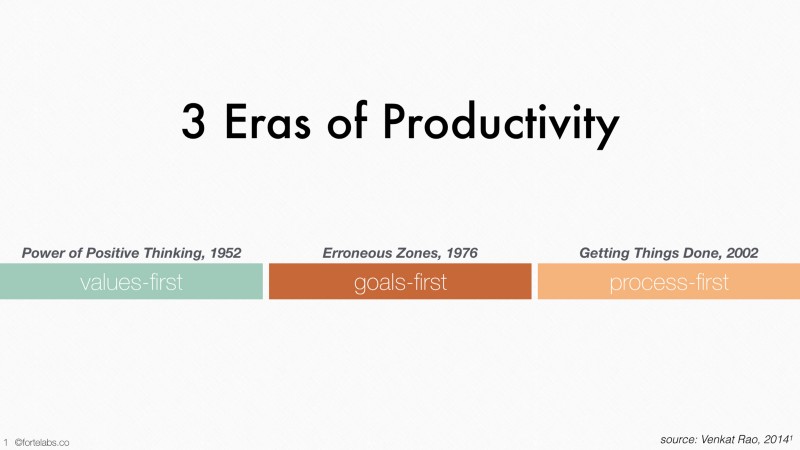

There have been 3 Eras of Productivity in modern times, each defined by a seminal book:

The Values-First Era at the dawn of corporate America told us that character was the most important thing. If you were a virtuous person, living according to principles and high ideals, you’d be successful. But then the cutthroat corporate culture of the 1980’s set in, and everyone realized they had to look out for their own interests.

The Goals-First Era came next, proclaiming that we should have clear goals to help focus our efforts. No one was going to give us a handout, so we had to ruthlessly drive toward the outcomes we wanted to happen. But goals too lost their luster. As the new millennium began and the uncertainty in the world spun seemingly out of control, we started looking for a process to follow.

We are now deep in the throes of the Process-First Era. A little over halfway through, if the average 25-year cycle holds. People march under the banner of their favorite process: Theory of Constraints, Six Sigma, Design Thinking, Agile/Scrum, Getting Things Done, Lean Startup, Habit Loop. Every aspect of modern work is being systematically distilled down to 5 steps that promise results if you’ll only follow the process

When it comes to personal productivity, the Process-First Era is most clearly manifested in our obsession with habits. Charles Duhigg’s book The Power of Habit (Amazon Affiliate Link) in 2012 kicked off a flurry of thought pieces, habit change frameworks, and products. Silicon Valley jumped on the bandwagon with a conference dedicated to creating habit-forming products. A stream of startups created wearable devices promising to help you stick to good habits.

The appeal of process-based habits is obvious: replacing a far-off outcome with a daily action makes it seem far more manageable. It gives us something immediate to focus on, in the midst of a highly uncertain environment. It distinguishes the fundamental building blocks of behavior out of which big achievements are made. The consensus is clear: goals are dangerous and unproductive — we should create habits instead.

But I think we’ve gone overboard in our love affair with habits. Discrete achievements still matter. I don’t care that I wrote X number of words per day — I care that I’ve published a book. I don’t care that I dedicated Y minutes to prospecting new clients — I care that I have a client list.

We don’t need to throw the whole concept of goals overboard in order to start making progress. We need to reinvent what goals are and how they’re formulated in a radically different environment than the one in which they were conceived.

In P.A.R.A. Part VI, I argued for the critical importance of “small-batch” projects in creating an effective Project List. I explained how tightly scoped projects with clean edges contribute directly to focus, creativity, and perspective.

In Part VII, I’ll share with you how to formulate the most important part of small-batch projects: desired outcomes. The scope and the deadline (the other two components) are easy to come up with. It is the desired outcome that defines and shapes what the project is and where it takes you.

FROM PRESCRIBING MEANS TO DESCRIBING ENDS

The key shift we need to make to formulate desired outcomes is from prescribing means to describing ends.

Traditional projects prescribe means: we will do X, then Y will happen, and then we’ll have Z. In a slow-moving environment, laying out all the steps in advance was both possible and effective. The more intermediate steps you completed, the higher the chances of success. Following the plan was actually more important than project success, because you could avoid blame if it failed.

Modern project-based work instead focuses on describing the end state of a project in vivid, exciting, yet objective detail. The purpose is to focus the efforts of a diverse group of collaborators on outcomes that are inherently, immediately valuable (instead of valuable only according to the plan, and “someday”). Many of the people working on the project may move on after it ends. They’re not going to wait around for a 5-year strategic plan to come to fruition.

Instead of “Deliver training manual” (a means), we want to ask “What will the manual improve, accelerate, enable, strengthen, accomplish, or increase?” In other words, what is the manual a means to? If it is to “accelerate employee onboarding,” that suggests multiple pathways: a live workshop? An online training? A pre-recorded video orientation? A peer mentoring program? We do need to commit to one of these for now to get started, but having these alternatives in mind will allow us to pivot quickly when new information comes to light. If the desired outcome is instead to “mitigate legal risks,” well that’s a completely different matter. In that case, you might just need some legal boilerplate and then be done with it.

Can you see how a group of collaborators discussing this project around a table are headed for trouble if they don’t agree on the criteria for success?

When we articulate these “desired ends,” just to be clear, we’re not saying they are “correct.” We’re not saying they are the ultimate, final ends. We’re not even saying they are necessarily aligned with the big picture. All we’re saying is that achieving them would be an inherently valuable, worthwhile result. Even if the only result is that we gain more learning about which direction we should be taking.

Paradoxically, the faster and sharper we want to turn, the further out we need to project our desired outcomes. Like a GPS navigation system keeping you headed for your final destination despite all the twists and turns you encounter along the way.

Most project outcomes I see people formulate don’t look further than the means. That would be fine if they at least had the end in mind. But when I ask what that is, the most common response is “Let me think about that…”

For example:

- Launch new website

- Deliver new feature set

- Finalize marketing campaign

- Finish reading book

These are outcomes, but not ones that are worthwhile in isolation. What I recommend instead is describing the success criteria. In other words, the standards or metrics by which success will be measured. For example:

Launch new website: New website is launched, with 10,000 unique visitors, $50,000 in sales, and 15% repeat customer rate by November 30, 2018.”

There is no ambiguity around this finish line. Either the website will be launched or it won’t. Either it will have 10,000 unique visitors, or it won’t. $50,000 in sales, or not. 15% repeat customer rate, or not. This will all happen by Nov. 30, or it won’t.

This outcome describes an end state. It outlines precisely “what will have happened.” It is very clear on what must be true for it to be considered successful, without prescribing any particular way of reaching it.

You’ll notice that this outcome has many ways of NOT coming true. You could even nail the first 4 metrics, but not by Nov. 30. Having more ways to fail is an important feature of project-based work: everyone wants to know as soon as possible whether a project is off track, because you’re getting paid for results, not time spent.

What tightly scoped projects with clear success criteria really do is surface assumptions. If you have a massive project taking up 80% of your time for the next 6 months, assumptions will only be revealed after the deadline has passed, and management or the client starts taking a hard look at what’s going on. By then, it’s way too late to take corrective action.

Precise outcomes are designed to reveal assumptions as quickly as possible. They are actually hypotheses — designed to be falsified. By making our projects small, we expose their inner workings to scrutiny. By writing falsifiable outcomes, our assumptions about what will happen by when become public records open to questioning.

DESIRED OUTCOMES AS HYPOTHESES

The fundamental nature of goals has changed, from forecasting an outcome to formulating a hypothesis that will yield maximum learning.

For example, one of my current goals is:

Forte Labs content is licensed to 5 people or businesses, producing $5k per month in revenue, by August 31, 2018.

This is a good outcome not just because it’s specific, but because there are many ways it could not happen, all of which will yield insights. Here are some of the questions underlying this goal:

- Once the licensing agreements are in place, how long does it take to onboard new licensees?

- Who will license my content? (“people and businesses” are vague, but I could continue to narrow these down as I gather more information)

- How much income will these licensing agreements produce? (the numbers imply $1,000 per license per month, but I really have no idea)

- How long will these contracts run for? (if I reach a $5k run rate by August, will that be easy to maintain, or require constant effort?)

- How long will it take to get licensing agreements written and approved by my lawyer? (reviewing this goal each month I’ll be able to track progress)

- What kind of support or updates will licensees require to maintain a subscription? Is it a one-time transaction or does it require building a relationship?

There are others, but this should give you an idea of how specificity surfaces questions. You can’t get specific without making assumptions. And as soon as you articulate those assumptions, you’re free to examine them.

This kind of goal is designed to be falsified, just like a scientific hypothesis. Answering any one of the questions above will require shifting the goal, which is exactly the point. I want the goal to track changes over time, getting closer and closer to reality as completion gets nearer.

This is not about trying to foretell the future or be overly rigid. The intention is to be able to look at the difference between what you aimed for and where you hit, and be able to ask and answer “why?”

There is a distinction here between precision and accuracy. In a corporate environment, they are closely linked: you had better only get precise if you know it’s going to be accurate. But when setting goals for yourself, even in a traditional corporate environment, being precise even at the expense of accuracy will yield the learnings you need to change reality to fit your intentions!

After all, the best way to predict the future is to invent it.

YOUR PROJECTS FORM A NETWORK, WITH INTERFACES DEFINED BY OUTCOMES

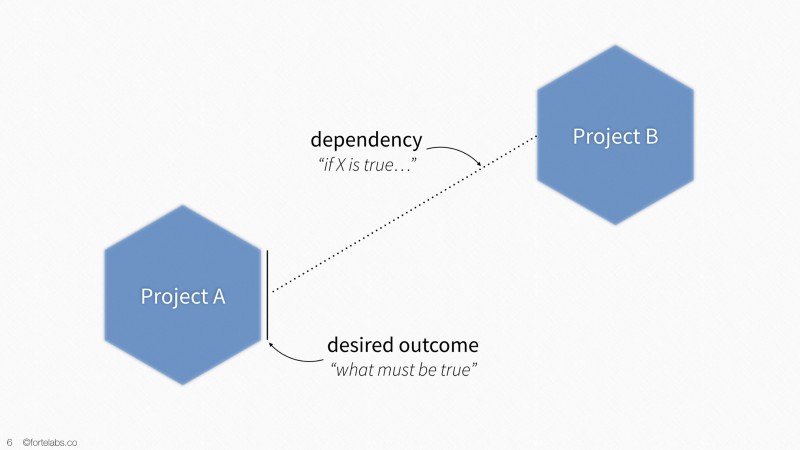

What you begin to create as you become more fluent in formulating desired outcomes is a personal productivity network. The Theory of Constraints calls this a Prerequisite Tree or a Necessary Condition Network, described briefly in this slide deck and in my upcoming articles in the TOC101 series.

This network is a map from where you are, to where you want to be. But the waypoints along that path are not “things you have to do.” That leaves you individually responsible for walking every step, expecting no help from anyone or anything.

They are “things that must be true.” And there are many ways for one of those statements to flip from “not true” to “true” that don’t require your direct effort: changes in the economy, software programs coming out with new features, shifts in the competitive landscape, new people coming into your life.

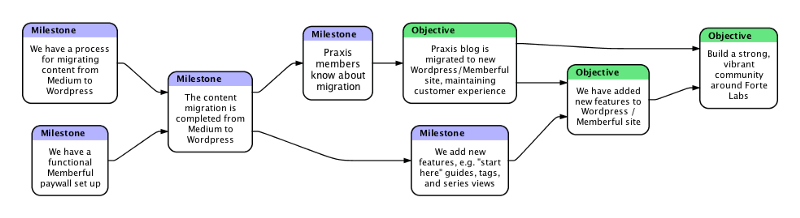

As an example, here is a prerequisite tree we created for transitioning Praxis from Medium to WordPress. It describes what must be true at each stage to proceed to the next:

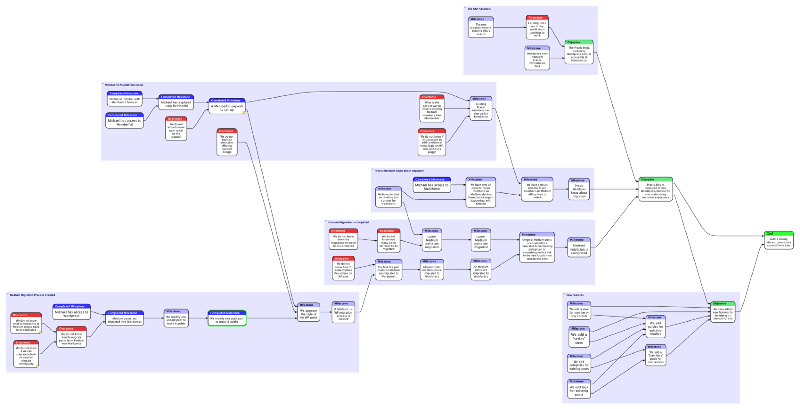

Each dependency can, of course, be broken out in more detail, revealing what must be true at a fine-grained level for these big milestones to be true. New information coming in or changes in scope can reconfigure the network, as you can see comparing the two more detailed trees below, from early in the project and late in the project:

Prerequisite Tree from early in the project, when dependencies weren’t clear

Prerequisite Tree from late in the project, as dependencies became more clear

By mapping out the network of necessary conditions for a new reality to emerge, you are opening yourself up to serendipity. You are positioning yourself to benefit from unexpected opportunities when they arrive at your doorstep. By elevating your perspective, you are moving from trying to wrangle individual nodes into submission, to managing the network effects, surges and pulses, feedback loops and bottlenecks that make networks so volatile, and powerful.

Your projects are the nodes in your personal productivity network. They are the containers into which information flows, intelligence is applied, and work is performed. Desired outcomes are the interfaces between these nodes, allowing projects to work together and become more than the sum of their parts.

All the guidelines and recommendations I’ve outlined in this article are designed to make those interfaces as clean as possible. A project could be an outstanding success on its own, but if it doesn’t have clean interfaces that can connect it to other projects, it will be a lonely beacon in the night.

Clean interfaces — clear desired outcomes — are what allow a project node to rely on its neighbors. To build upon and extend the momentum of the ones that came before. If it’s unclear where a project begins and ends, it’s like an irregularly shaped, fuzzy node. Like Legos, not having a clean edge means it can never become a piece in a beautiful new creation.

It’s worth adopting a standardized definition of “desired outcome,” even if you don’t accept mine. That’s because you have much bigger things to worry about. You are the manager of the highway system — you can’t afford to be performing safety checks on individual cars. Standardizing and semi-automating the way you formulate your projects allows you to ascend to a higher horizon: managing portfolios of projects.

Any given project on its own is trivial. But as part of a portfolio, they can change the world.

Follow us for updates on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!