ChatGPT's success caught even its creators off guard. The technology itself wasn't new—it was just packaged differently. In her latest piece for Learning Curve, Rhea Purohit explores how psychological factors, rather than technical capabilities, often drive the adoption of revolutionary technologies. Drawing parallels between ChatGPT's meteoric rise and the original Macintosh's role in popularizing personal computing, she reveals how understanding human psychology might be the key to unlocking AI's true potential.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Nearly two years ago, on November 20, 2022, ChatGPT was released.

The app went viral.

The world was excited, scared, and maybe a little skeptical.

But for the first few months, executives at OpenAI were…confused.

Why?

In purely technical terms, ChatGPT wasn’t a giant leap forward in the state of the art. In fact, it wasn’t new at all. OpenAI’s GPT models had been around since 2018, the original ChatGPT was a fine-tuned version of GPT 3.5, and most of the technology inside it had been available as an API long before its release. Even so, ChatGPT became one of the fastest growing apps on the internet, with an estimated 100 million monthly active users two months after its launch.

OpenAI executives were bemused.

Jan Leike, who at the time led OpenAI’s alignment team, which worked on making AI systems behave as per user intent, said in an interview after the chatbot’s release, “I would love to understand better what’s driving all of this—what’s driving the virality…It’s not a fundamentally more capable model than what we had previously.”

Later in the conversation, Leike answered his own question: “[W]e made it more aligned with what humans want to do with it.” He continued, “It talks to you in dialogue, it’s easily accessible in a chat interface, it tries to be helpful. That’s amazing progress, and I think that’s what people are realizing.”

ChatGPT went viral because it wrapped AI’s growing potential in a remarkably familiar interface—chat. It didn’t create new capabilities, but presented existing ones in a different way. ChatGPT redefined our relationship with AI as a culture—and what moved the needle was a change in the way we think about LLMs, not the raw power of the technology itself.

The technical barriers to advances in AI matter, but the psychological ones that hold us back from adopting them are just as important. Even the most sophisticated models might fail to deliver on the promise of AI if the average individual, for deeply human reasons, decides not to use them. Let’s take a closer look at the psychology of how we adopt new technology as a culture—and how that influences the way we build with AI, and use it in our work and lives.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes

Revolutions are sometimes grounded in shifts in perception. This is not a new idea—twelve years ago, advertising messiah of the Ogilvy Group Rory Sutherland echoed a similar world view. “The next revolution may not be technological at all, it could be psychological—a better understanding of what people value, how they behave, and how they choose could generate just as much economic value as the invention of a hovering car or some new form of electronics,” he said.

Hovering cars aren’t here just yet, but if you stop and think about the devices we use everyday, you’ll notice many are the result of a change in our thinking—not in our technology.

Take the way you’re reading this article, for example.

As you scroll through this piece, whether you’re reading on your phone, your laptop, inside the beveled edges of your inbox, or on Every’s website, you’re interacting with a computer through graphical user interfaces (GUI).

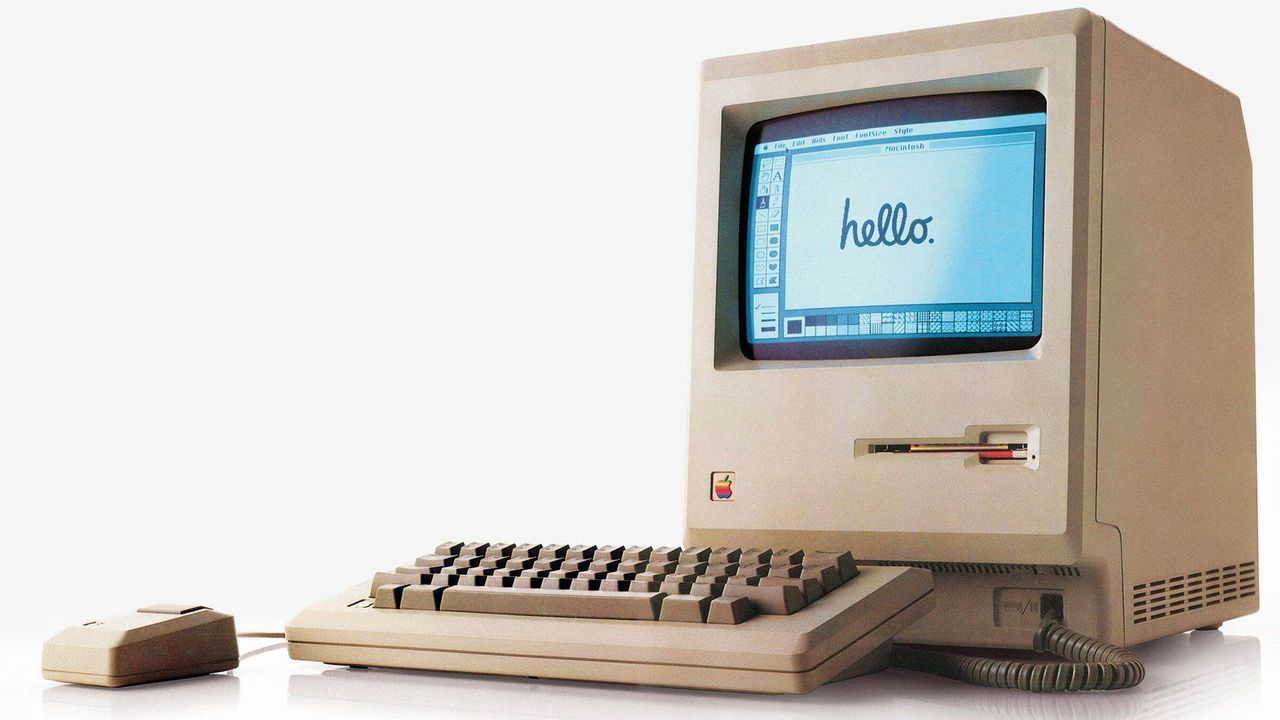

GUI is a way of interacting with computers through intuitive visual elements like buttons, icons, and menus. Before GUI, using a PC meant typing long strings of green alpha-numeric characters on a black screen. GUI—along with the mouse’s functionality to point-and-click on these visual elements—enabled the personal computing revolution. And the computer credited with popularizing this technology is the original model of the Macintosh, which was released in 1984.

However, the Macintosh wasn’t the first computer that used GUI. It doesn’t even take second or third place (the Xerox Star, and another computer manufactured by Apple, the Lisa, launched in 1981 and 1983, respectively, both had GUI and point-and-click devices). The Macintosh didn’t earn a place in history because of its technical specifications—the device is special because it popularized the idea of a “friendly” computer. This philosophy goes right down to how the Macintosh was designed to resemble a symmetrical human face.

The disk drive was shifted to the bottom right to make the machine resemble a human face. Well, a weird, oblong-shaped face. (Source: BBC.)The Macintosh didn’t earn significant revenue for Apple. It was slow, incompatible with several apps, and had a laughably small memory. Yet it led the personal computing revolution because it successfully sold the idea that everybody could—and more importantly, actually wanted to—use computers. Before the Macintosh, computers were largely confined to the backs of offices, for the select few who knew how to use them. The Macintosh brought them inside people’s living rooms, making computers—those complex, intimidating machines—far more accessible. It forever changed the way people thought about an existing technology. That’s why I believe that the next big breakthrough in AI has less to do with algorithms, data, or compute—and more to do with you. Specifically, it has to do with the way you think.

What really drives the adoption of a new technology

Each time a new version of an LLM is released, my X feed is filled with a dizzying number of posts that measure the change in the model’s technical capabilities. Predictions about how more powerful models will revolutionize human existence are scattered across the internet. We’re falling into the trap of measuring our progress solely by advances in technology, and it feels like we’re always breathlessly waiting for the next breakthrough.

AI models might get better with time, however, just like with ChatGPT and the Macintosh, the path from innovation to impact is not linear. The way we think plays a big role in whether or not we would actually use a product.

I was curious about the psychological factors that influence the adoption of a new technology, and after some back and forth in Perplexity, I found my answer in a theory known as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). UTAUT, as its name suggests, consolidates a body of research about how humans integrate new technologies into their work and lives. It was first developed in 2003 by a team that included Dr. Viswanath Venkatesh, a professor of business at Virginia Tech who researches how technologies are implemented in various settings. In their initial research, the team studied how employees adopted workplace technologies, including a proprietary accounting software and an online video conferencing platform that reduced their reliance on in-person meetings. Dr. Venkatesh later conducted an experiment that extended UTAUT to consumers buying a new technology. In 2021, he outlined a framework for studying AI adoption using the same principles. Over the years, UTAUT has become a foundational framework to understand how technology is adopted in different contexts.

UTAUT is grounded in four main variables that explain how humans think about embracing a new technology: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. Each one is a lens through which to look as we build, market, and use AI products.

Performance expectancy

When OpenAI launched the o-1 model in September 2024, the company marketed the model’s advanced reasoning capabilities by releasing a series of videos that displayed its prowess in various situations. It decoded a Korean cipher and helped a geneticist conduct research on edge case diseases. Because a large language model is a versatile tool with broad applications, these videos told users why the technology was useful. By doing so, OpenAI was influencing its users’ performance expectancy.

Performance expectancy is the degree to which the user believes the new technology will be useful to them. In a professional setting, this is typically reflected in an increase in the user’s efficiency, making this metric a measure of extrinsic motivation—behavior that’s driven by external rewards or pressures, rather than internal satisfaction or enjoyment.

Effort expectancy

Consider how AI’s mainstream success differs from crypto’s slower adoption. As one Reddit user noted, crypto is “complex, cumbersome, and requires a ton of focused knowledge to not lose money.” In contrast, the conversational chat interface of LLMs made AI accessible enough to have the technology go viral. It had a positive impact on the effort expectancy of their users.

Effort expectancy is the perceived ease associated with the use of a product. The importance of this variable peaks in the early stages of usage, trailing off with time and sustained use.

Social influence

All LLMs answer the questions you ask them, but Perplexity is on a mission to keep your sense of wonder alive. It seeps through in the abstract, thought-provoking images its CEO regularly drops on X, clean, understated designs of Perplexity merchandise (like sweatshirts and hats), and carefully chosen custom sans-serif typeface on its website. The company has built a brand around evoking a sense of curiosity.

Phi Hoang, a brand experience designer at Perplexity, described the genesis behind the company’s brand, explaining that they avoid focusing on specific AI models in their messaging because the end consumer doesn’t care about these details. Perplexity scores high on the UTAUT’s social influence scale, helping it accumulate a loyal following of niche power users.

Social influence is the extent to which a user perceives that other people—specifically those whose opinion they hold in high regard—believe that they should use the new technology. In other words: the extent to which the user thinks it’s “cool” to use it.

Facilitating conditions

Imagine you’re sitting in a cafe with your cofounder, minding your own business and coding in AI code editor Cursor. Suddenly, the app crashes. You exclaim in frustration—and just like that, someone stops by and offers to get it up and running. He does it. You realize he’s the cofounder of Cursor.

This level of customer service might not be scalable, but Cursor surely would score high on the facilitating conditions variable.

Facilitating conditions refers to the degree to which a user believes there are platforms to voice their concerns and resources to support them as they use a product.

A new way to think about technological progress

In the last two years, Jan Leike has resigned from OpenAI and started a new job at Anthropic. He’s probably not confused by the success of LLMs anymore. UTAUT is a framework that brings clarity to Leike’s questions around the viral success of ChatGPT, and academics are publishing early research about how the theory applies to the adoption of AI tools, proposing the addition of new variables like the degree to which individuals are willing to trust an autonomous, intelligent system, and their attitudes toward the risks associated with AI.

I also see the essence of the theory being applied in features that present new ways for users to interact with AI. Claude’s Computer Use, which allows the model to use the computer to actually complete tasks, like browsing the web, creating and editing files, or running code, plays to the effort expectancy of the tool. Canvas in ChatGPT, which enables users to work with the AI in a collaborative workspace, as opposed to being restricted by a chat interface, positively influences performance expectancy.

While the frontier AI companies work on pushing the boundaries of technology, we can create the next AI breakthrough for ourselves—as builders, leaders, and learners—by understanding the psychological factors that drive or inhibit user adoption. The future of AI isn’t just better algorithms, data, or compute. It’s also a better relationship with technology.

Rhea Purohit is a contributing writer for Every focused on research-driven storytelling in tech. You can follow her on X at @RheaPurohit1 and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We also build AI tools for readers like you. Automate repeat writing with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Write something great with Lex.

.11.33_PM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

The technical breakthrough itself does not quickly become popular, but rather the psychological factors triggered by the product that results from the application of technical innovation

Wonderful, thank you for this provoking and thoughtful piece.