Content Warning: Eating disorders and references to diet culture.

Noom’s literature on weight loss is full of lofty guarantees, even for a weight loss app. Get life-long results. Stop dieting. Get fit for good. Change how you think. Learn about psychology. Break bad habits. Try “The Best Diet”—this one is different. Actually, Noom is more like an “anti-diet.”

Like Weight Watchers, SlimFast, Jenny Craig, The Atkins Diet, and countless fads before it, Noom is the new solution to long-term weight loss that everyone is talking about. In 2020, the app generated $400 million in revenue (double the amount from the year before) and gained more than 50 million downloads in response to demand. (Since the pandemic began, nearly 61 percent of adults in the U.S. gained weight, averaging about 15 added pounds.) Last month, the company announced a $540 million Series F, gearing up to a potential near-future IPO with a $10 billion targeted valuation.

Noom has been around in some form since 2007; the company's founders, Saeju Joeong and Artem Petakov, started the venture by selling stationary bikes with a connected calorie-counting app. It wasn’t until 2017 when Noom was released in its current iteration: a weight loss app that employs calorie counting, a rating system that assigns colors to different foods, small group support, and behavior change techniques. These days, the company’s website says it wants to help people “live longer and experience the gift of true physical, mental, and emotional well-being” while simultaneously referring to itself as a “growth machine.”

Noom is ‘moon’ spelled backward. According to one outlet in 2017, Petakov said the name was chosen because “the moon is calm, wise, and always there for the whole world." With each Noom ad I was served over the long course of 2020—on YouTube, Google, Instagram, a million podcasts—I failed to grasp what wisdom was on offer, or what made this app worth a potential $10 billion. Could mixing the prospect of weight loss with a subscription model really be all that revolutionary? Is encouraging behavior change to achieve thinness a scientific breakthrough? Why are these thin model-types telling other people how to lose weight? The more ads I saw, the less I understood, and the more eerily familiar the language and imagery became.

Much like the moon itself, maybe Noom had a dark side.

“But it’s science!”

In its simplest form, Noom employs calorie counting and a color-coded system as its two levers to induce weight loss. Every day, “Noom Nerds” are prompted to log their meals and snacks in detail with a maximum caloric intake in mind, labeling each item with either green (all you can eat), yellow (eat in moderation), or red (eat sparingly) tags.

Noom’s color-coding system isn’t their invention; it’s called the traffic light diet, and it was designed in the 1970s for children to use as doctors began worrying about rising childhood obesity. (It is still recommended by pediatricians, though studies on the efficacy of the system have been entirely inconclusive.) Noom isn’t the first weight-loss app to use the traffic light system either; Weight Watchers launched Kurbo, a diet app for kids, back in 2019 and was immediately met with significant backlash from eating disorder researchers, therapists, dieticians, and doctors. Critics say that the traffic light diet isn’t an accurate depiction of balanced eating because many healthy foods, like avocados or nuts, are highly caloric and so relegated to the “red” (or “stop”) category. Additionally, being trained to think of foods around a ratings system can encourage anxiety and guilt around food choice, potentially leading to harmful or unnecessary restriction.

Indeed, programs like these lay out the playbook for disordered eating—the spectrum of behavior that sits between normal eating and eating disorders—and throw gasoline on the fire of our collective cultural tolerance of anti-fat bias. As Christy Harrison, a registered dietitian and author of “Anti-Diet: Reclaim Your Time, Money, Well-Being and Happiness Through Intuitive Eating,” wrote in her New York Times piece on the subject, anti-fat bias (also known as weight stigma or fatphobia) among children and adults actually poses a “greater overall health risk than what people eat, and about an equal risk as physical inactivity.” This claim isn’t mere conjecture—it’s based on a study published in Annals of Behavioral Medicine, and reflects the consensus of dozens of scientists from top hospitals and universities worldwide that anti-fat bias has real and measurable negative health impacts.

But companies tend to build where people fail and fatphobia spun into a golden currency for the diet industry. Weight Watchers famously led the charge.

Weight Watchers was founded in 1963 by Jean Nidetch, a housewife and mother who, after her own weight loss journey, found that combining the “Prudent Diet” (a one-pager distributed by the New York City Board of Health), weekly support groups, and a rewards system for weight-loss milestones was a recipe for success. Weight Watchers was primarily geared toward women from the start, and as of 2017, women still make up about 90% of the company’s core demographic.

Since the company went public in 2001, its revenue climbed almost every year, peaking in 2012 at $1.83 billion. But something in the culture was shifting. By the mid-2010s, diets were out, and body positivity messages from thin white women were in. By the fall of 2015, Weight Watchers reported 10 straight quarters of declining sales. Their mission to help women diet their way to happiness had begun to feel out of date and out of touch. The $1.5 trillion wellness era had begun, and wellness—as anyone who uses the word to sell something will tell you—is not about losing weight.

It’s about a holistic approach to health that unleashes your best self! In wellness world, vitamins are not just supplements but mission-driven companies that can change your life for the better. Earlier stereotypes of holistic health were woo-woo hippies who composted and ate granola. The modern image of wellness is sleeker, more minimalist, and Instagrammable. Self-care, a pillar of the wellness movement marked by the consumption of things like CBD bath salts and meditation apps, is now an active daily pursuit for millennials, a generation plagued by student debt, monetizable hustle, burnout, and a byzantine healthcare system that remains unaffordable or unattainable for millions.

By 2018, Weight Watchers hatched a plan to face the wellness industry head-on by rebranding to WW and adopting a new tagline: “Wellness that works.” At first, the WW rebrand was a success, bringing a rally of subscriber growth in 2018. In May 2020, the company announced it was cutting $100 million in costs and letting go of a large number of employees. But as the pandemic wore on—with folks gaining weight while stuck inside—WW’s stock started to go up, rising by 62% since January.

With parallels to Noom’s growth in the past year, it seems like 2021 is an exciting time to be a weight loss company. Noom even goes so far as to market itself as “Weight Watchers for millennials,” which makes sense from a branding perspective. Weight Watchers was the weight loss program of record (Oprah! Points! Bread!) for a long time. But what makes Noom more alluring to millennials than WW is its native use of wellness language—a vernacular that we now all speak fluently.

Though decidedly about losing weight, the centerpiece of Noom’s ads is the repeated use of terms like “lifestyle change” and “psychology,” which are scientific-sounding reassurances used to prop up wellness products. Thin, attractive people sit on couches, beaming over the number of pounds they’ve lost by thinking differently. One Noom user standing next to a rack of clothes says in one ad that “weight loss came naturally” for her by rethinking habits. “If you change up here,” she says, pointing at her head in another ad, “everything will fall into place.”

Noom’s assurances that it will “break down the sciency stuff” into “easy to understand tidbits” is a great way to tell folks they don’t need to look too closely at what’s behind those tidbits. The company claims that it is grounded in evidence-based science, and to its credit, they have published a number of peer-reviewed scientific articles. However, none of these studies support Noom’s central marketing claim: that it will help you lose weight and keep it off for life. The study they cite to support this was published in 2016 and tracked users for only 72 weeks. I reached out to Noom to find out if they’ve conducted any significant studies to gauge the long-term efficacy of their app since 2016; they did not respond for comment.

The key to helping users keep weight off in the medium- to long-term, Noom says, is its use of “goal-oriented psychotherapy treatment.” When I asked Dr. Gina Merchant, a behavioral scientist, what that term means, she told me she hadn’t heard of it before. “It’s marketing, and that’s the point,” she said. “We don’t see companies publishing [academic research] on long-term behavior change, and if that’s what they’re hedging all their bets on, it’s not sustainable,” she said.

It’s significant that Noom is claiming scientific backing and using scientific-sounding language while promising not to overwhelm users with any actual science. A 2019 study that examined 73 of the most highly ranked mental health apps found that scientific language was the most commonly used strategy for supporting claims of an app’s actual effects on health. But only about half of these apps were backed by academic evidence, and a third claimed to deliver scientific techniques for which no evidence could be found. The study is consistent with the proliferation of pseudoscientific marketing in recent years, where repeat offenders like Goop and runaway trends like natural deodorant exacerbate the popularity of fringe science when it comes to the products we use.

Here’s what science does tell us:

Studies show that people who follow popular diets like paleo or keto gain back any weight loss after about a year. They also show how yo-yo dieting (also called weight cycling) may increase risk for heart disease, particularly in women, as well as many other physical and emotional issues. Numerous studies even link crash diets to slower metabolisms and weakened immune system, elevated stress levels, and self-harming behaviors like alcohol abuse and self-induced vomiting, to name a few.

Still, I wanted to know—is Noom different?

Noom and me

For research purposes, I decided to become a Noom Nerd myself.

When I sign up, I complete some questionnaires around how much weight I want to lose and the reasons why. The app sets my target calorie intake to 1,200 calories per day, which is considered a restrictive diet and too low for some people (most food labels are based on a 2,000 calorie diet). I log everything I eat and drink with its corresponding labels (oat milk = green food; chicken taco = yellow food; roasted almonds = red food; homemade pickles = green food; pesto = red food; chickpea pasta = yellow food).

On the movement front, Noom is already tracking my steps and I’m prompted to track any additional exercise I complete. Noom then pairs me with a Goal Specialist, a human who messages me to set weekly goals and action plans. Educational content on nutrition and weight loss is also sprinkled throughout the app’s UI. Every day, I’m expected to complete a weigh-in.

After three days, I messaged my Goal Specialist to cancel my subscription. Counting calories and weighing myself every day is too triggering, as these were the exact methods I used to lose weight when I was 13 and suffering from a severe eating disorder. For me, calculation was the key to getting thin—a numerical swirl of calories in, calories burned, and the blinking red figures that stared up at me on the scale each morning was the constant, most pressing math problem in my head. I counted on my way to the bus stop (1 scoop of cereal = 300 calories). I counted during gym class (20 minutes of running = 100 calories gone). I counted during pre-algebra (300 - 100 = 200 calories).

Given that an estimated 30 million Americans experience an eating disorder at some point over their lifetime—with binge eating being twice as high, bulimia nervosa being five times as high, and anorexia nervosa being three times as high among women than men—it’s likely that many of you are familiar with some of these strategies that haunted me well into my late adolescence, and hold a spectral presence in my day-to-day even now. In fact, even as the wellness industry emerged and reached dominance with its claim that it wasn’t trying to change us, a study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that the rate of diagnosed eating disorders doubled between 2000 and 2018. I looked back at Noom’s ads promoting “lifestyle change” and “behavior change” and cringed.

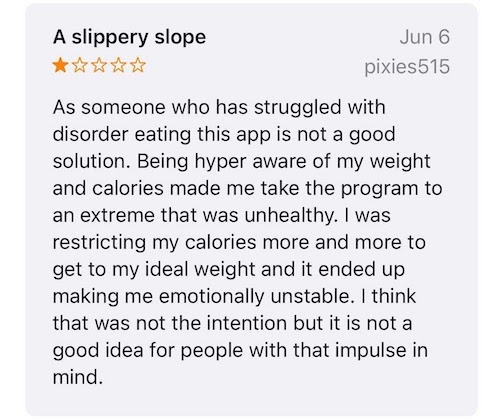

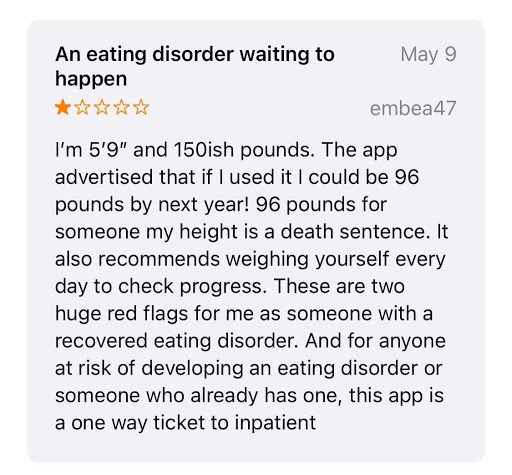

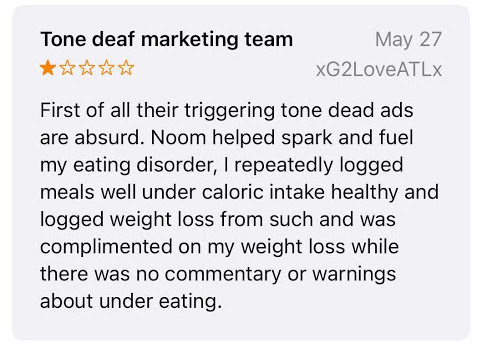

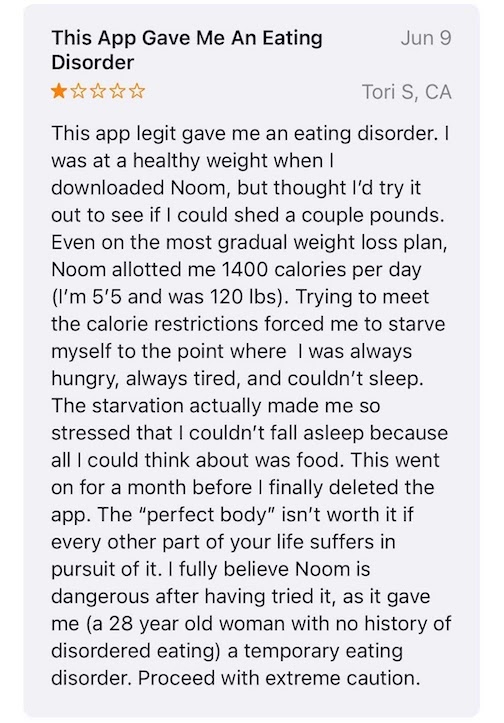

In researching this story, I found grim solace in the fact that my reaction to Noom was also experienced by others, many times over:

For an app that many have found encourages, induces, or triggers disordered eating, it’s also interesting that Noom goes so far as to bill itself as “anti-diet” in its marketing. Anti-diet as a term is commonly used by multiple movements to reject the diet industry and culture around it, such as Health at Every Size (HAES), intuitive eating, body positivity, and fat acceptance. With roots in fat, queer, feminist rebellion groups like the Fat Underground of the 1970s, the anti-diet movement promotes overall well-being rather than size reduction, as well as a weight-neutral approach to healthcare.

Noom isn’t weight-neutral—it’s an app that values thinness. That’s why Noom writes a lot about “burning belly fat” on its blog and why it uses weigh-ins as a fear-mongering tactic. It’s why Noom asks you if you have a wedding or vacation coming up in its onboarding flow, assuming that those are events that you might want to lose weight for. And it’s why I wasn’t screened for a possible history with disordered eating upon arrival, or why the app’s promise of “personalization” through a customized diet plan falls flat.

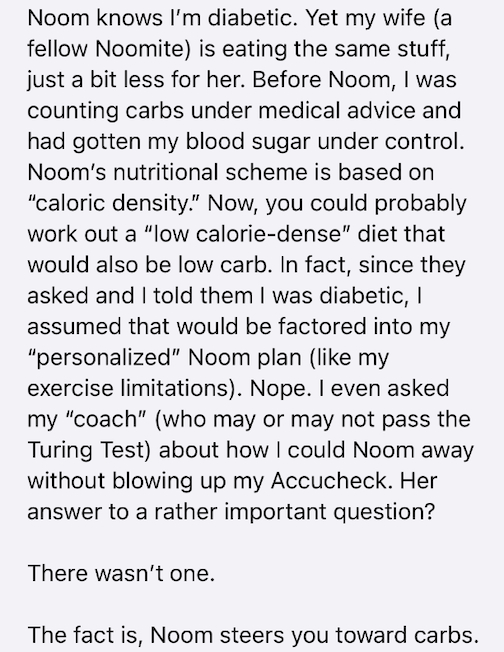

In reporting this story, I found that many folks experienced the same restrictive calorie recommendation that I did regardless of weight, height, activity, or health conditions. If you’re a nursing mother, Noom won’t recommend that you eat extra calories (which breastfeeding mothers need). If you’re a diabetic, Noom won’t carefully count your carbs to control your blood sugar levels (which people with diabetes need). Set point weight theory—evidence that our bodies have a preset weight baseline hardwired into our DNA—is thrown to the wind.

Noom does incorporate human “health coaches,” though not registered dieticians, into its programming in attempts to personalize the experience, but many people have reported slow response times, random responses to specific questions, and the general feeling that these coaches are bots instead of real people. There’s even a subreddit called r/NeglectedNoomates for people who “love Noom but feel the support group/coaches are lacking” and are seeking additional support. One redditor recently posted their first check-in with the group, writing, “I'm just a regular person that's been neglected and going through rough times. I'm still here though. Middle school has been tough with everything going on.”

The fact that Noom sells personalization but delivers largely standardized guidance is scalable as hell; Noom is even lauded in a number of marketing blogs as a growth hack darling. It’s a strategy that has similarly been used by sleep tracking apps, which have also come up short in offering personalized advice on how to solve sleep problems in recent years. Like Noom, sleep apps can trigger negative hyperfocus on one’s own metrics; as Brian X. Chen wrote in his New York Times piece on the limits of sleep tracking, using a sleep app actually has the potential to worsen insomnia by making people obsessed with achieving better sleep (a condition now called orthosomnia).

If anything, Noom is a master class in onboarding conversion—test it out, and you’ll quickly find that it’s really hard to not pay for their service. So hard not to pay, in fact, that hundreds of customers have complained to the Better Business Bureau, detailing unwanted credit card charges, a lack of refunds, and the inability to reach Noom directly about these issues. There’s also a class-action lawsuit filed against the company for its failure to obtain users’ consent before charging them with an automatic renewal program. The complaint claims that Noom has utilized the pandemic to its advantage, promising a “zero cost” trial period because many people are experiencing financial hardship.

But unsatisfied customers are a short-term risk. Noom could eventually make it easier for folks to cancel their subscriptions. They could revise their screening process to better meet the needs of people with chronic illness or a history of disordered eating. I wouldn’t bet on Noom, not because they can’t make money, but because investors should make healthier choices.

Let me be really clear: this essay is not a judgment of anyone who has tried Noom or hopes to reduce their size. Losing weight can be a great thing and is scientifically proven to garner health benefits for many kinds of people. What worries me is how a well-funded app has drawn upon the most harmful, exploitative aspects of disordered eating, fatphobia, and pseudoscience to repackage a not-new diet for millennials and make a ton of money in the process. The real danger here is the promise of fantasy bodies and fantasy lives to those who are most vulnerable—they only have to pay $59 per month for it.

My brisk experiment as a Noom Nerd happened to bump up against several other life events that stripped me down of my usual defenses, making me feel unregulated. A person close to me died suddenly the month prior, and grief started to show up both sporadically and crushingly. Freshly vaccinated, my immediate surroundings also started to change. I first wanted to rejoin the city I live in wholeheartedly, and then not at all. Loss haunted me. My routine was disturbed. My eating habits became unhinged.

I didn’t eat any food until dinner time on some days. Other days, I would bake a cake for breakfast because I woke up starving and craving a block of sugar. While I typically eat a pretty healthy diet with regularity built-in, I’ve worked hard to combat the compulsion to control the meals I eat with extreme strictness because, simply, that’s the only thing that ever helped me have a better relationship with food. But regret and shame and self-loathing started to build as my grip on the cognitive ropes I used to control the other parts of my life started to slip. I should not have eaten that cake.

In an exposed moment, Noom got in touch with me. Not directly, but through an ad on Instagram. This one prompted me to take a quiz that would reveal how long it would take to reach my ideal weight. For a moment, it felt like they had seen everything I’d been going through and saw an opportunity for conversion in my pain. Then I rolled my eyes and clicked my phone shut. I knew it wasn’t personal.

Edited by Rachel Jepsen

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!