Sponsored By: Axios HQ

Today’s newsletter is brought to you by Axios HQ, intuitive software from Axios that helps your team think more clearly, communicate more crisply, and send focused, effective updates.

Fortune 100s and startups alike use Axios HQ to craft smart updates that distill essential information in half the time—increasing transparency, boosting engagement, and building trust across the organization.

Innovative teams know communication is the key to culture, connectedness, and growth, and use HQ's intuitive platform to elevate company updates and get their teams smarter, faster.

Hey, Nathan here! Today I have a guest essay for you written by Matt Ragland, about the nascent development of a big new part of the creator economy: college athletes. I think you’ll love it. Matt is the perfect person to write about this: he was employee #5 at ConvertKit, the first customer success hire at Podia, and currently runs The Whatever Company, an agency that helps creators monetize their knowledge through courses. He lives in Nashville, TN with his wife and three boys.

Here’s Matt. Enjoy!!

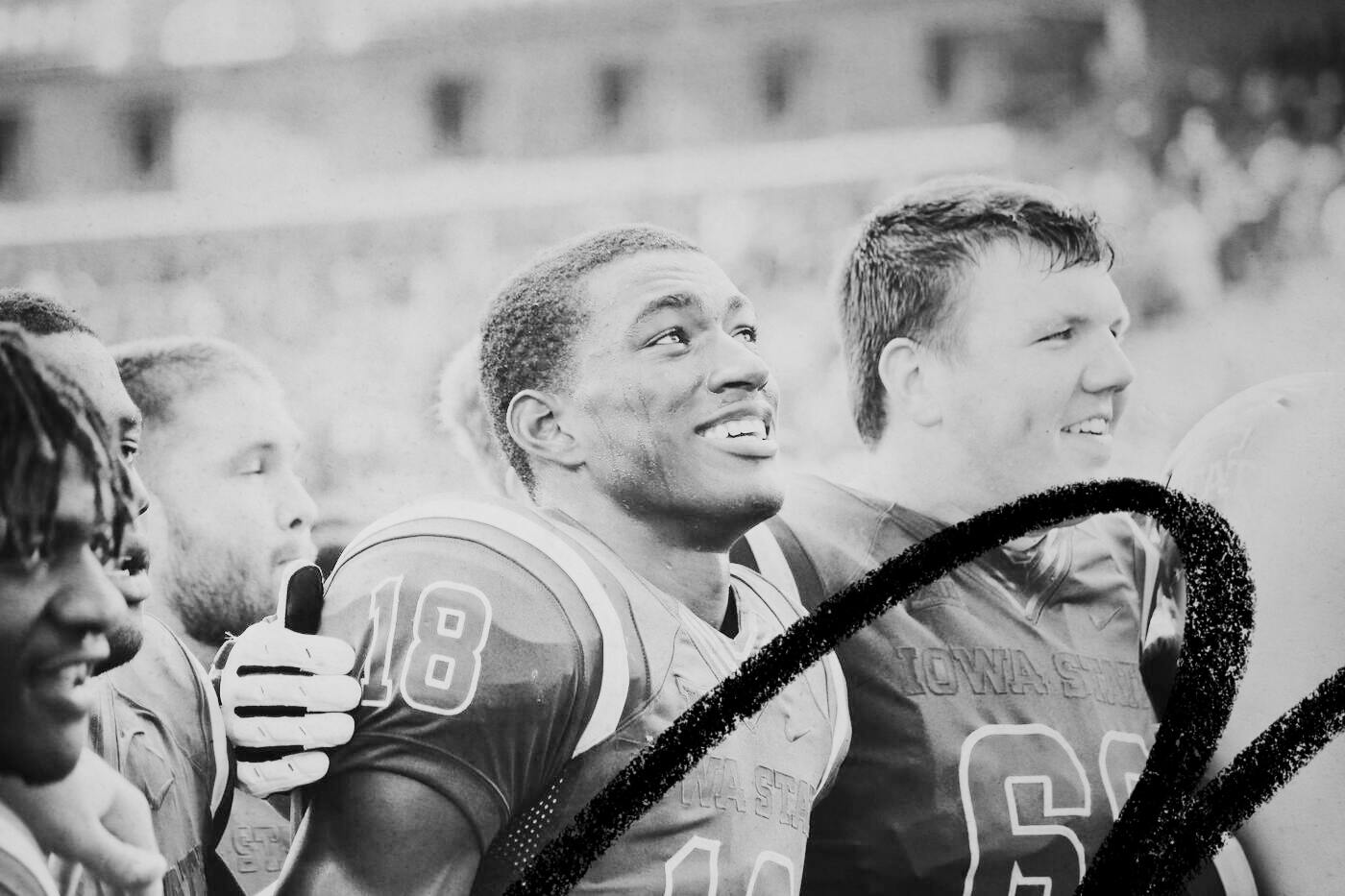

What if I told you there is a class of influencers with followers and fans numbering in the millions… but they are unable to make a single cent off their name? Until this past summer, that was exactly the case for thousands of college athletes going back decades.

Athletic departments pay millions of dollars to coaches and spend even more on facilities for athletes to train, eat, and relax in. It’s a setup that rivals the top tech companies. Great workspace, free food, a place to take a nap or play video games… but none of the employees are paid for their work. Individual athletes have huge fan bases, consistent output, and offer after offer of brand partnerships, but until recently they have been actively prohibited from making any money off of what they do. Colleges still refuse to treat athletes as employees deserving of compensation, but a change in the laws this summer has allowed athletes the chance to seek their own remuneration. Taking lessons from creators before them and adding some new twists of their own, college athletes are poised to become an important part of the creator economy, and are building a lot of wealth along the way.

After legal challenges brought by Ed O’Bannon (a former UCLA basketball player) and Lebron James began in California in 2019, other states began making moves to allow college athletes to make money. On July 1st, 2021, 41 states produced legislation that allowed an athlete to profit off their “name, image, and likeness”—referred to as “NIL.”. No state laws are exactly the same, and neither the National College Athletics Association (NCAA) or federal government appear to be in a rush to hand down broader rules that apply across athletics. (The NCAA’s existence is at risk after the Supreme Court’s decision that the NCAA effectively operates an antitrust association that exploits student-athletes.)

Let’s set aside the economics and ethics of whether schools should actually pay their athletes and the real value of athletic scholarships. What never made sense was an individual athlete’s inability to profit off their own platform and audience because of outdated ideas of amateurism.

The idea that a creator or performer should be paid in “exposure” is increasingly seen as exploitation, yet that’s essentially what’s been happening for decades under NCAA rules. Playing in college sports may seem like a great opportunity, but college athletes give up a lot, including the health of their bodies and advanced academic opportunities, with a very small chance of making it to a professional league. The fact is only 2% of college athletes have any kind of professional career, with an even lower number signing a professional contract for life-altering money. The natural time constraint of college athletics also presents a unique situation. Even “super senior” players only have six years to maximize exposure and revenue, so the clock is ticking from the moment they step on campus.

The NIL laws are seeking to change the opportunity gap in college athletics, and have led to a flurry of sponsorship deals, merch drops, and much more for college athletes across the country. Within days, agencies and apps launched to support athletes' connections with businesses and facilitate deals. College athletes are getting top dollar for their talent and audience now. As any creator knows, that is a very good thing.

This essay will explore the ways players are finally profiting off their talent and audience and how it intersects with developments in the larger creator economy. The billion dollar industry that is college athletics has just been blown wide open (and we haven’t even talked about web3 yet).

Athlete Opportunity

The rise of social media influencers and brand opportunities has made a college athlete’s audience more valuable than ever before, regardless of their sport. In the past, only the star quarterback or point guard would have the recognition necessary to command sponsorship deals. The NIL laws open up an entirely new world for gymnasts like LSU’s Olivia Dunne to ink deals with athleisure brands, Minnesota’s gold medal winning wrestler Gable Stevenson to start training with the WWE, and Marshall football player Will Ulmer to accept tips at open mic night.

Let’s take a look at the audiences top college athletes are building and the potential opportunities for revenue and monetized exposure. Dunne tops our list with 5.7M followers on TikTok and Instagram. Stevenson has 67K followers on Twitter. Fresno State basketball players Haley and Hanna Cavinder have 3.7M on TikTok with personal Instagram accounts over 300K. The Cavinders, Stevenson, and Dunne may be outliers, but any content creator pitching brand deals knows there is plenty to go around regardless of audience size. Here’s what sponsorship expert Justin Moore told me about the expanded reach of top college athletes...

Athletes can sometimes command 2-3X the rates of other digital creators with a similar following. This is due to many brands and ad agencies assigning a “halo effect” to the indirect association with the athlete’s team (even if the team has no involvement in the deal).

The most popular athletes can facilitate their own deals and name their price to brands. Alabama football coach Nick Saban made news at SEC media days when he said QB Bryce Young had signed 7-figure deals before his first start. Clemson QB DJ Uiagalelei signed a deal to appear in Dr. Pepper’s Fansville commercials. The Cavinder twins signed a deal with Boost Mobile that landed them on Times Square billboards.

It’s more than brand deals though. Athletes are creating their own logos and custom merch with a direct-to-consumer model. Here are the most common and popular examples of athletes generating revenue through NIL deals.

- Brand sponsorships. Ga'Quincy “Kool-Aid” McKinstry signs a deal with, well Kool-Aid.

- Appearance fees. Miami QB D’Eriq King signs with the Florida Panthers hockey team to appear at games and post on social media, and more in a first-of-its-kind “collaborative partnership” between a college athlete and professional team.

- Apparel. Kentucky basketball player Dontaie Allen released his own apparel.

- In-kind exchanges. Florida QB Anthony Richardson gets a new Dodge Durango or similar car from a local dealership every 3-6 months until the end of 2023 season.

- Commercials. KU football walk-on Jared Casey books an Applebee’s commercial after a game-winning catch to beat Texas.

- Autographs. Any college athlete can set up a table and charge for autographs (this is historically one that has been a “violation” in the past).

- Professional contract commitment. As mentioned, Gold Medal wrestler Gable Stevenson signs a commitment and training contract with the WWE.

- Social media shoutouts. Michigan State Kicker Matthew Coghlin gave a paid shout out to a podcast he’s never listened to… but is sure it’s not terrible.

- Art sales. Southern Methodist DB RaSun Kazadi is able to sell his art directly to fans.

- Tips. Musician Will Ulmer can accept tips at open mic night and appearance fees at music and art festivals.

- Patronage. Organizations like Gator Collective are cropping up to support athletes through paid fan memberships. I’ll talk more about this one below.

Connecting Athletes, Brands, and Fans

The first few months of the NIL rules have launched a multitude of new platforms, agencies, and connections between brands and athletes. The fastest brands to act were those with direct involvement and connections with the local team, as in the case of All-American LSU DB Derek Stingley & Walk Ons restaurant. Ohio State freshman QB Quinn Ewers even left high school and enrolled early just to sign his own NIL deals with local companies.

But star players at colleges with high-profile athletics programs were always going to have their pick of deals and brands to work with. The long tail of NIL is connecting more companies with more athletes at a range of price points and audience numbers. Matchpoint and Opendorse are platforms that connect athletes and brands by finding the best fit of payment and exposure. They’re similar to existing influencer platforms but with a niche focus on the needs and legal requirements of brokering deals for college athletes.

Another way players are going to direct to fans is through enterprising alumni-led groups like the Gator Collective. Gator Collective operates with a Patreon-style model with 800+ active members who make monthly pledges from $5.99 to $999.99, and allocates 85% of funds directly to athletes. In return, members get exclusive interviews, access to merchandise deals, raffles for autographed items, and more.

Athletes, agencies, and platforms will continue to work together to build opportunities of long-term wealth creation and ownership. There are many reasons to believe the athlete’s deals are going to follow the script of social media influencers for early opportunities and developments. The top athletes will have their own support teams and agents to find and filter the best deals. Other enterprising athletes will make a higher-than-expected profit because of their niche and positioning. Then the long tail opportunities between other athletes and companies will be facilitated at scale by apps like Opendorse and Matchpoint.

Part 3: The Future & Web3

The future of NIL can be drastically altered by Web3, giving athletes direct ownership of digital assets and currency—in fact, college athletes are already developing their own crypto tokens and NFTs. We’re seeing early glimpses with Kayvon Thibodeaux's $JREAM token and Luke Garza’s $41K (19.9 ETH) NFT sale to benefit Iowa Children’s Hospital.

It’s possible that the natural privacy of crypto payments will have an unacknowledged impact on college athletics going forward. In the past, college programs have relied on the anonymous “bag man” to illegally persuade top recruits to commit to their school. The bag man delivers the cars, cash, homes, and even jobs to family members that can sweeten a college offer—though officially none of this ever happens. Even with the new NIL rules, “buying” players by offering perks or outright cash is still against NCAA regulations. A school booster or business cannot make NIL payments or offer deals to high school recruits as a way to “encourage” commitment. The “bag man,” already a known entity in college athletics recruitment, may find a welcome loophole in non-trackable payments—who’s going to know if a young player was given BTC in a hardware wallet?

Above board, NIL and web3 can go even further than an individual athlete’s ability to build an audience and book brand deals. NFT drops and marketplaces can become a revenue driver that benefit each and every athlete. For context, NBA Top Shot’s model also pays out a percentage to all players, not just to the player featured in the highlight. Specific payouts are not public, but the 5% fee from any Top Shot sale is split between the marketplace (in this example, Dapper Labs), the NBA itself, and the Player’s Association. A similar model could create a meaningful revenue stream for all athletes—not just the stars—without affecting current university or conference budgets and live-viewing rights deals.

If I ran a major athletic department or conference, I’d be in talks with a company like Dapper Labs (the marketplace partner for NBA Top Shot and NFL All Day) or Candy Digital (Major League Baseball) to build my own white label NFT marketplace. 2021 has shown strong use cases for each of these NFT offers with many more in the coming years. Here are just a few opportunities already validated by professional leagues and marketplaces:

- Trading cards

- Replay "moments" (like Top Shot)

- Event access

- Mascot PFPs (think Bored Apes for your school)

College fans are notoriously, well, fanatical, and the opportunity to own a play like the Iron Bowl Kick Six or Christian Laettner’s buzzer-beater would bring in previously unrealized revenue streams. The revenue from athletic department-driven NFT sales could be split up by players on the team with an additional percentage going to any long-term medical care or education.

And who knows? Maybe somewhere along the way every school can figure out how to pay college athletes fairly. Until then, it’s exciting to see talented and entrepreneurial college athletes able to promote, play, design, sing, and sign their way to six and seven figure paydays. College athletics is ripe for disruption in ways that few markets are. The creator economy has been a movement to champion the talent of artists, makers, and exploited workers. NIL is just the first step in empowering young athlete entrepreneurs to leverage their talent and audience—but you can be sure it won’t be the last.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!