When I was 25 I invested in GoPro—which at the time, believe it or not, was a hot company. They IPOed that summer at $35, had an incredible run-up to $87 that fall, and then cooled off to the mid $50s that winter. A friend of mine loved GoPro, and infected me with this narrative that their hardware could avoid commoditization through content and community. So I decided to get in while the getting was good.

Turns out, a lot of times when you think you’re being greedy when others are fearful, you’re actually just being dumb when others are smart.

I bought GoPro at $52 per share, and pretty much instantly regretted it. As I watched the money leave my bank account I realized I didn’t know anything about their business, I didn’t own one of their cameras (hadn’t even used one, honestly), and the only reason I bought the stock was because a random friend liked their surfing videos. Call it “post investment clarity.”

Over the next few weeks, my investment kept shrinking. Of course it did. I didn’t want to sell for a loss, but had no faith it would rebound. I was paralyzed and avoided thinking about it, like a stack of dirty dishes, which only made the problem worse.

Then, a miracle: the stock bounced back to $52—no idea why—and I was able to sell for a small profit. I was free.

Shortly thereafter, GoPro crashed for good.

So what does this harrowing tale have to do with Peloton, you might be wondering?

Well, I’m now older and theoretically wiser, but I just bought the dip of a consumer hardware company on the theory that content and community can provide it a bulwark against commoditization.

But screw it, this time could be different!

Why I Bought $PTON

I think of Peloton as something like an angel investment—but liquid from day one, and with limited downside. Despite the fact that they are a public company with billions in revenue, an investment today is basically a “team and dream” bet. Peloton is embarking on a new journey led by a new CEO that promises to fundamentally reshape the company.

At the highest level, this is what’s happening:

- The revenue is moving from one-off hardware sales to recurring subscriptions

- The content is moving from in-house only to a more open platform (I wrote in detail about this last month)

- The fitness modality is expanding beyond spinning to all types of workouts

- The capital investment strategy is moving from mostly hardware-focused to mostly software- and content-focused

It’s a high stakes bet that will affect millions of Peloton users and determine the future of one of the largest and most interesting companies in fitness.

If you think it has a decent shot at working, as I do (we’ll go over why I feel this way in the next section), then now is probably a good time to make the bet. Thanks largely to their recent troubles and partially to an uncertain macro environment, Peloton is pretty damn cheap right now. Their current market value is $8.8 billion, but they had $4.1 billion in revenue in the past 12 months (a mere 2x multiple) and $1.2 billion in gross profit (7x multiple). It gets better. Their current valuation is just a 6.5x multiple of annualized subscription revenue alone. This is way out of range of most comparable growth-stage subscription businesses.

But just because a stock seems cheap doesn't mean it’s actually a good buy. (See GoPro above.) What interests me most about Peloton is their new strategy.

I first started sniffing around Peloton when they fired their CEO last month and hired a new one, Barry McCarthy, who previously was the CFO at Spotify and Netflix. I wrote an essay unpacking what I thought they would do based on what McCarthy was saying in interviews at the time. I wasn’t sure if it would work or not, I just wanted to understand it.

Since then, a few interesting things have happened:

- The stock kept getting cheaper

- They started to roll out pricing experiments they previously had only hinted at

- Some big equities analysts issued bullish forecasts

- The stock started climbing

This is all short term stuff. Nothing here should fundamentally change our view of what the company is capable of doing. But it did increase my confidence that McCarthy is really going to do what he said he was going to do, and it helped that people smarter than me—or who at least have much larger spreadsheets than me—also think this is a good bet. So I decided to pull the trigger.

I got in at $22.51 per share on March 15th, and bought an amount that is reasonably responsible, but still made me a little nervous. Since then I’ve earned a 22% return, which is not bad, but it doesn’t ultimately mean anything. This is a long term bet, and if the stock had gone down by 22% in the first week I wouldn’t have concluded anything meaningful from it, so I shouldn’t do the opposite just because the result happens to be in my favor.

The way I’ll actually judge performance of the investment is simple: over the next few years, does Peloton seem to be on track for making their new strategy work?

Here’s how I’m thinking about that question as of today.

Peloton’s New Strategy

In my last post about Peloton I mostly focused on how they plan on opening up their platform to 3rd party creators and developers, and why that’s so important to ensure stable, growing demand over the long run. I don’t have any significant updates to my thought process on that front, so if you haven’t read it and are interested in this plank of their plan, I’d encourage you to read it here.

In this post, I’m going to focus on their other strategy change: moving from one-off hardware sales to ongoing subscriptions. This is going to be a fascinating development to watch.

There are three problems this is meant to solve:

- Buying a Peloton is an expensive commitment, limiting their addressable market

- Once you buy a Peloton you probably won’t upgrade for a really long time, limiting their long term revenue growth

- Hardware sales are chunky, seasonal, and unpredictable, which makes it hard to plan expansion and growth initiatives. (This is exactly what bit them in the butt and got their founding CEO fired.)

By shifting to subscriptions, Peloton is essentially shifting revenue today to revenue further out in the future. Instead of getting $1,500 for a bike today and $49 each month from each subscriber, they are betting they’ll make more money if they get $0 today and $100 per month from each subscriber into perpetuity. They are betting that the increase in growth they can get by effectively lowering the price and commitment will more than offset the probable increase in churn they will see when they shift to this model.

I wanted to understand how sensitive these variables are, so I created a toy spreadsheet model to figure it out.

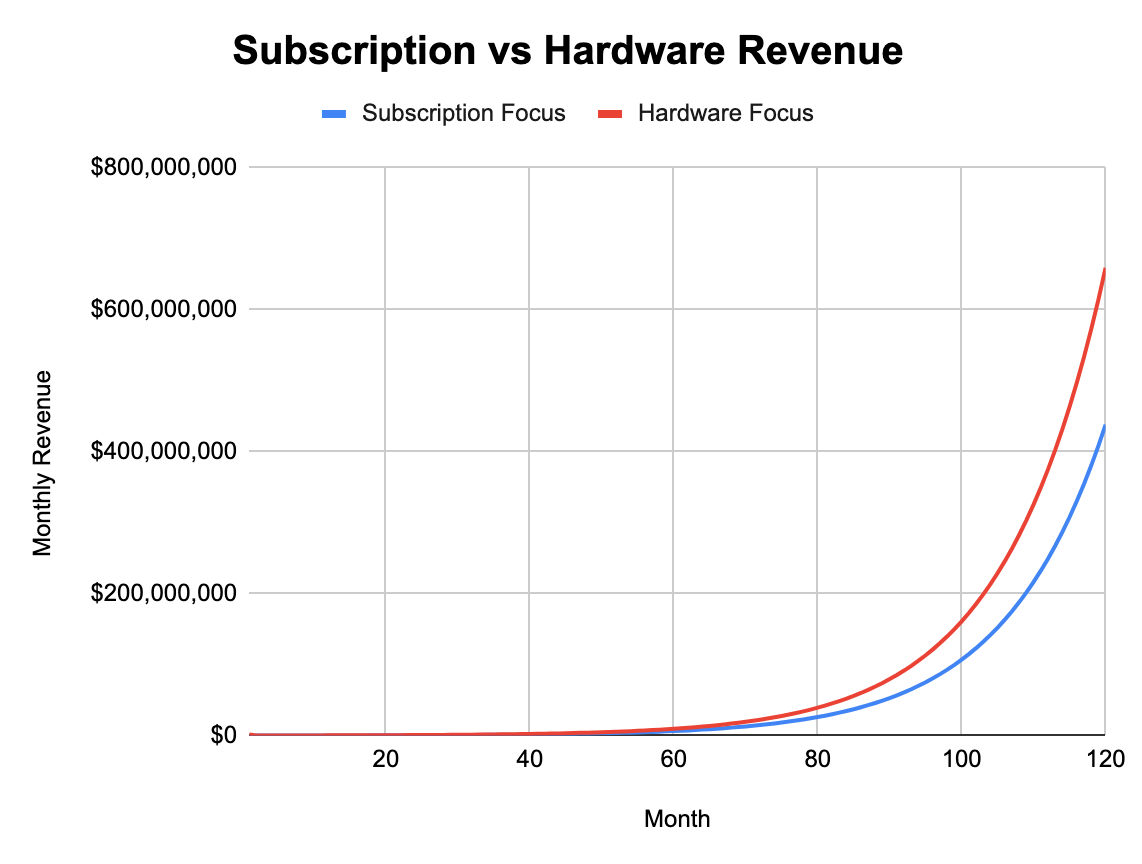

First, I wanted to compare to see how much revenue each strategy could generate assuming they had the exact same growth rate and churn.

Hardware focus:

- Bike price: $1,495

- Subscription price: $39

- Monthly churn: 0.7%

- Monthly growth: 8%

Subscription focus:

- Subscription price: $100

- Monthly churn: 0.7%

- Monthly growth: 8%

Holding growth and churn constant, the Hardware focus actually outperforms:

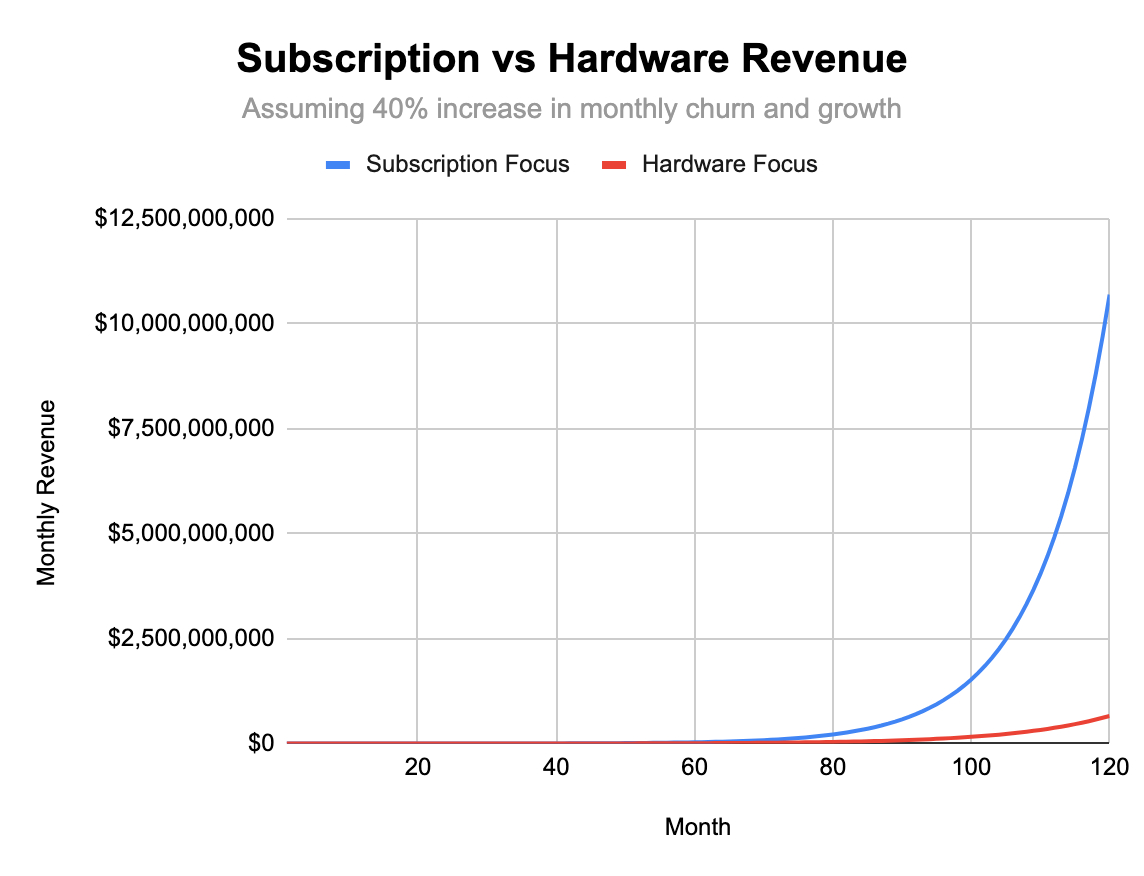

Now let’s make it a little more realistic. How much do we think churn and growth will increase by when they shift to the subscription model?

Let’s say churn increases by 40% to 0.98%, and growth also increases by 40% to 11.2%. What do you think would happen in this scenario? Should it basically even out, since monthly churn and growth are both increasing proportionally?

Not even close:

In the long run, the increase in growth massively outweighs the increase in churn. Of course, 8% monthly growth is extremely difficult to sustain over 10 years, let alone 11.2%. But the point of this model is not to forecast Peloton’s future revenue, it’s to understand the mathematical effects of increases in growth and churn when we hold everything else constant.

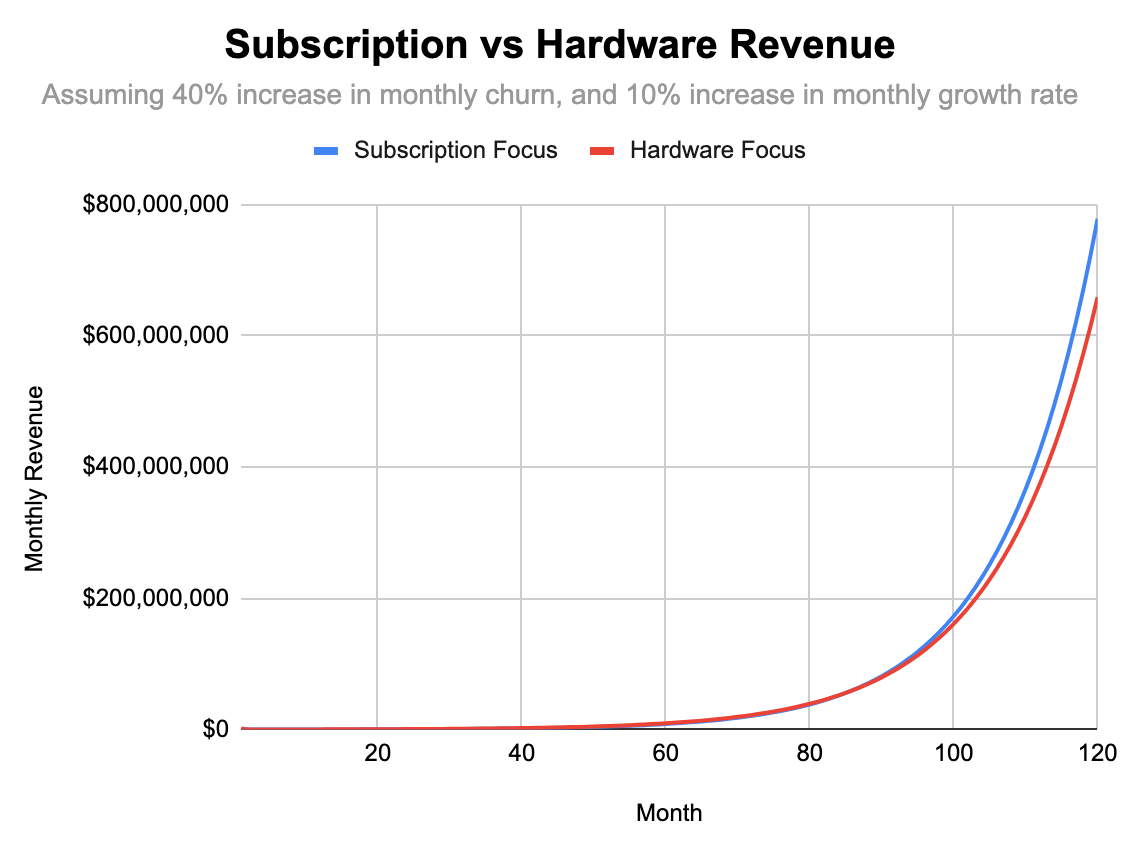

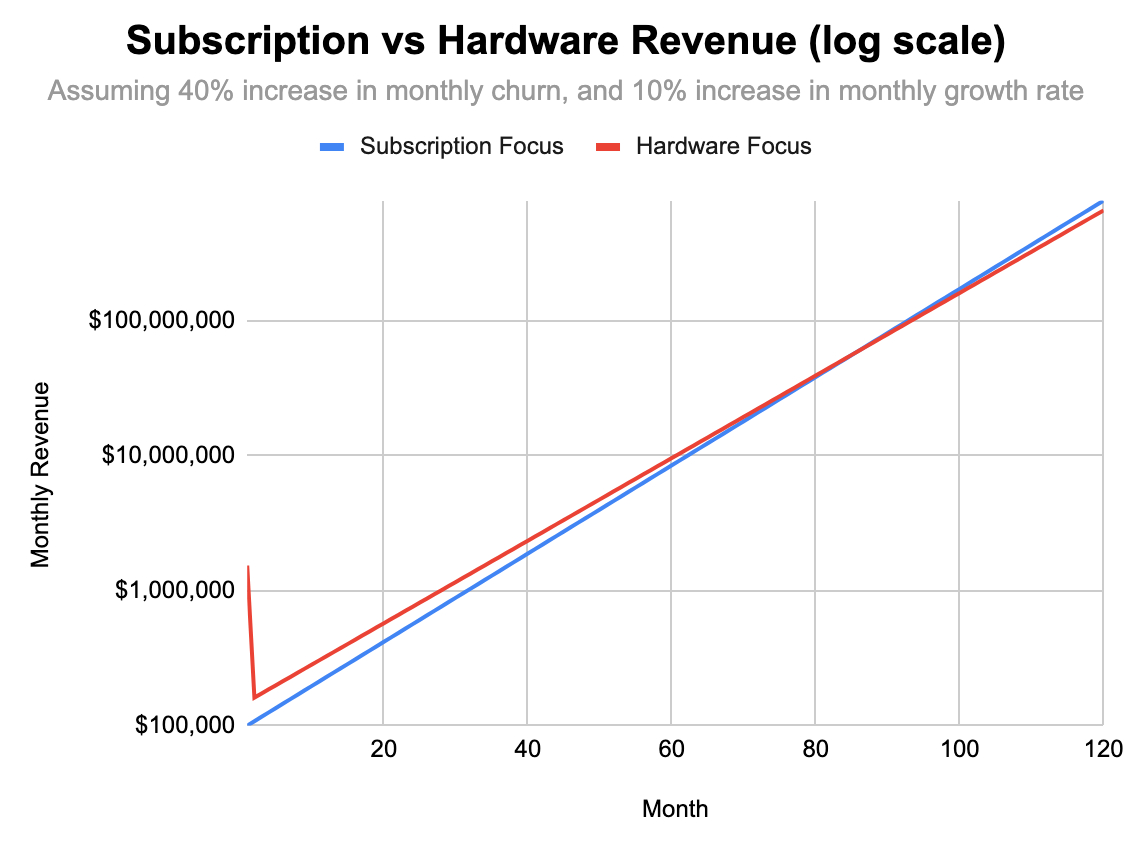

Even if you think they’ll see 40% increases in churn and mere 10% increases in monthly growth rates, the subscription-focused model still comes out ahead:

One interesting implication of this chart is that the long run effects tend to swamp everything else, since it is predicated on the idea of exponentially compounding growth over time. The early parts of the chart are hard to see, but there is something interesting going on there. Here it is again in log scale so we can see it:

What you see there is the mathematical representation of the claim I made at the beginning of this section:

“Peloton is essentially shifting revenue today to revenue further out in the future. Instead of getting $1,500 for a bike today and $49 each month from each subscriber, they are betting they’ll make more money if they get $0 today and $100 per month from each subscriber into perpetuity.”

So what does this mean? If you’re a long-term investor in Peloton, you should pay close attention to churn and subscriber growth, but less attention to top-line revenue growth over the next year or two. It’s also why Peloton is testing this strategy in the market to see what sort of increases in growth they experience, rather than debating about it internally. At the end of the day nobody knows if this is the right strategy, because it all depends on a few numbers in a growth-sensitive equation.

I like Barry McCarthy’s perspective on this from an interview in the WSJ: “There is no value in sitting around negotiating what the outcome will be. Let’s get in the market and let the customer tell us what works.”

A New Growth Market: Private Training

Of course, the growth equation McCarthy is optimizing is not only about subscriptions vs hardware. It’s also about the content people experience through that hardware, and the types of workouts possible to do on it. This is why the move to open the platform is also so important. I would actually argue it’s more important than the shift to subscriptions, but it will take much longer to execute and is more difficult to A/B test.

In my last essay I pretty thoroughly covered why I think it’s a great idea for them to shift to open up content from third party providers and creators, but there’s one important part of that which I entirely missed: private training.

My wife and I have been working with a trainer via FaceTime for six months, and it’s been incredible. We work out from home with some basic equipment, and have a real relationship with a real person. The advice and accountability he provides has been so much better than when we used to have a Peloton. It’s easy to skip a session with a famous instructor who has no idea who you are, but it’s much harder to bail on a calendar invite with a friend.

At first I thought this was a threat to Peloton, but actually I think it’s an opportunity: they can totally create an OS and a marketplace for private training. Whether 1:1 or small group, I think there are a ton of fitness influencers and personal trainers who specialize in a variety of disciplines and have a variety of vibes that people would absolutely pay for. Peloton could have a 10–20% take rate, like Substack, which would be small enough to not tempt people to move off-platform especially if they are funneling demand to trainers.

I also think this is a huge area where better core OS functionality could make a big difference in the training experience. Right now my wife and I just do basic strength training via FaceTime, but it would be amazing if our trainer could see our biometrics on his end, and see how that changes over time in response to different levels of training load. Or even see our history across other trainers or classes we might take. The social and gamification elements would be more valuable if integrated into personal training sessions as well.

This is more speculative, because as far as I know Barry McCarthy hasn’t mentioned anything about it. But when you’re talking about turning Peloton into an OS, this seems like a total no-brainer to me.

And the coolest thing is: since they own the hardware, they are one of the few subscription companies that can truly go direct to consumers without paying the Apple tax or incurring Apple’s platform risk.

That’s it

So yeah, that’s why I’m investing in Peloton. I am curious to hear what you think—where did I get it wrong? How are you thinking about the opportunity in front of the company?

Also, Barry McCarthy, if you’re reading this, email me! Would be amazing to chat and/or interview you. I’m [email protected].

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!