My recent interview with Jesse Beyroutey solidified a hunch that I’ve been nursing for awhile:

Incentive alignment is one of the most important ideas in business, but making it work in practice is incredibly tricky.

Sure, you might understand the general principle — businesses who have incentives that are aligned with their customers tend to grow faster than those who don’t — but recognizing the logic of an idea and making an idea actually pay off are totally different things.

In order to put it into practice, you have to learn what good incentive alignment actually feels like from the inside. Case studies about companies that have done it successfully always feel much cleaner, simpler, and more inevitable than any business does in real life.

In real life, there isn’t just one principle — be it “incentive alignment” or anything else — that wholly determines your success. Instead, there are many forces; many details to integrate. It’s hard to know which to pay attention to. This makes even the biggest successes feel messy on the inside.

But if good and bad businesses both feel messy, how do you know if you’re on the right track? This question is especially relevant to tiny startups that are just getting started, but every company faces questions of strategic health which are impossible to measure in any analytics dashboard.

The solution is to develop a feel for how incentive alignment plays out in practice by learning the details of how it’s happened in different industries — to use history to improve your perspective.

This essay shares history from three different industries, to illustrate three different obstacles to making incentive alignment pay off.

- DTC ecommerce —how Warby Parker cut out the middleman 10 years ago, but is still tiny compared to the “complete rip-off” incumbent, EssilorLuxottica.

- Income Share Agreements (ISAs) — how Lambda School’s model copes with the fundamental tension in their model between the interests of employers, students, and investors.

- Subscription media — Sometimes what people want isn’t what they need, and even though subscription media businesses like The New York Times and The Athletic are generally better than ad-supported businesses, it doesn’t give them a free pass.

The common thread between all these stories is they all illustrate some of the limitations of incentive alignment. Nobody is arguing that it’s a silver bullet, of course. But in order to move beyond the first step (explaining the idea and why it matters) we need to add nuance, and to complicate the narrative.

“God is in the details,” Mies van der Rohe once said. I find that it’s equally true of architecture and business.

So let’s dive in :)

What is “incentive alignment” and why is it important?

Incentive alignment is a quietly popular idea. People relate to it in a totally different way from “disruption” or “the lean startup.” There’s no buzzword on everyone’s lips. Instead, the evidence of our belief is in our behavior.

When you hear talk about DTC brands cutting out middlemen, or about ISAs being better than tuition, or about subscriptions being better than ads, the alignment hypothesis is right there. You just have to read between the lines.

The theory hasn’t been formally stated anywhere that I can find, so here’s my stab at it:

“The Alignment Hypothesis” predicts that companies that profit from doing things that are in customers’ best interest will outcompete those who profit from doing things that customers don’t like.

The idea is that customers always will choose the option that’s best for them. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll choose the cheapest option. Instead, it means the most aligned with their goals.

(For example, with luxury products, part of the goal is to signal wealth, so it actually helps that the price is high, and for the luxury brand to advertise to a wide set of consumers, not just people who can afford them.)

You want to align your business model with your customer’s interests as much as possible, because businesses tend to prioritize actions that help them make money, and ignore things that are maybe nice for their customers, but don’t seem to contribute directly to the bottom line.

What does this look like in practice? Let’s take a look at Warby Parker, for example.

Warby Parker’s long-term alignment

Warby Parker creates eyeglasses, and sells them on their website and in their retail stores.

How is this especially aligned with customers, you might ask? Because in comparison to EssilorLuxottica, the main incumbent in the eyeglass industry, Warby Parker is practically a charity:

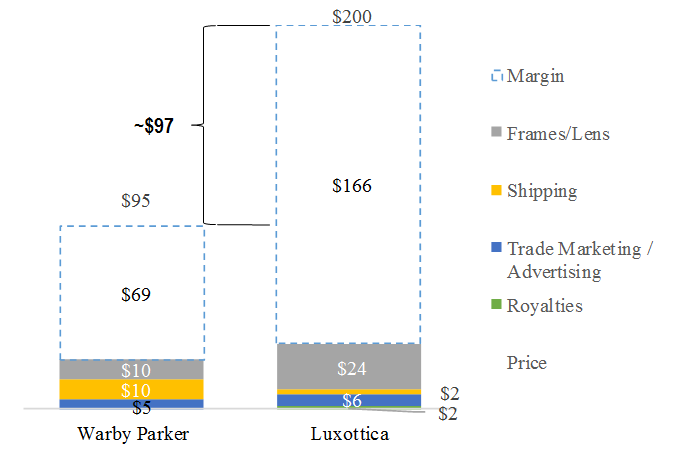

(Source: UCLA Anderson supply chain blog)

EssilorLuxottica was able to get away with such high margins because they had a near monopoly on distribution, and brand licensing with fashion labels like Prada, Coach, etc. They sell designer glasses that cost $15 to manufacture for prices as high as $800.

“I know. It’s ridiculous. It’s a complete rip-off,” said the founder of LensCrafters, which was acquired by EssilorLuxottica in 1995.

Of course, some people pay $800 for glasses because subconsciously they want you to know they paid $800 for glasses. But most consumers don’t behave this way, and just want good quality at a reasonable price.

Warby Parker saw the internet as an opportunity to offer something better for those people. They built a website that let them get around EssilorLuxottica’s distribution channels and charge a much lower price to customers. Importantly, they still had great, trendy designs and made a decent profit on each pair of glasses.

They launched in 2010, and pretty soon it was apparent that the plan was working. They grew fast, and kicked off a wave of DTC ecommerce businesses that’s still going to this day. Their last funding round in 2018 valued them at $1.75b. Any quarter now, they might go public.

This is a near perfect example of the alignment hypothesis at work. It’s a sort of corollary of the efficient markets hypothesis: you can’t offer people a bad deal for long, otherwise someone will come around and offer them a better one: lower price, higher value, etc. In this case, EssilorLuxottica failed to see that the internet enabled a new path to customers, with fundamentally different economics. The internet didn’t have to exist for too long before somebody (Warby Parker) came around and noticed the opportunity.

But obviously markets aren’t completely efficient. We do see bad deals all the time. And sometimes even startups that come along and offer better deals still take a long time to displace the incumbents.

EssilorLuxottica earned €17 billion in 2019. Warby Parker is still tiny compared to that. My rough estimate of their 2019 revenue is around $500–$600 million.*

*How I got to the $500m estimate, for the curious:

Warby is estimated to have earned $340 million in 2017, and were targeting 40% revenue growth for 2018. Let’s say they did that for 2018 and 2019. If they hit it, that’d put them at around $650m in revenue for 2019. Realistically, I bet they’re closer to $500m, because usually companies tend to decelerate growth as they scale, and especially when you’re a private company, it’s easy to set aggressive targets that are hard to hit.

If Warby Parker actually hit anywhere near those numbers, it’d represent extremely solid growth, and would likely put them on the path to make a serious dent in EssilorLuxottica’s business. But even now, 10 years after launch, even with optimistic assumptions about their growth since 2017, they’d still only be at roughly 3% of EssilorLuxottica’s current size.

In other words: they’re probably on the right track, but still have a long way to go.

So, what can we learn from this? Even in the most seemingly clear-cut of examples, where you’re offering a high quality product at a significantly lower price, taking advantage of a new distribution channel to get around an old monopoly, the world doesn’t change overnight.

In order to make a dent, you have to be patient.

The “alignment hypothesis” predicts that Warby Parker will succeed — but it doesn’t promise any particular timeline.

So, why hasn’t Warby Parker grown faster? If I had to highlight a single factor, I’d guess it’s that most people still prefer to buy glasses in a retail store where they can easily try on a lot of pairs. This is why Warby invested in their own brick and mortar stores. But, unlike with the internet, it’s going to take them a long time to build enough stores to reach as many people as EssilorLuxottica can with LensCrafters, Sunglass Hut, etc.

It makes me wonder: if timeline is one factor that complicates the alignment hypothesis, what are the others?

To answer this, let’s take a look at another great example: Lambda School.

How Lambda School balances multiple stakeholders’ incentives

Before Lambda School popularized ISAs, the main way to pay for a coding bootcamp was with cash.

For example, at General Assembly (where, full disclosure, I used to work) it currently costs $16k to take their 3-month software engineering course. In order to take the course, you’d pay in a few big installments during the course, or up front, all at once.

The problem, of course, is that students are not really paying to take a course. They’re paying to get a programming job. And the latter is a much riskier proposition. Nobody likes to pay tens of thousands of dollars when there’s a big risk that you won’t actually get what you’re after.

Enter ISAs. The theory is that by only charging students once they get a job, and by charging as a percentage of what they earn, the school’s interest is aligned more directly with students. This gives the school an immediate financial pressure to help students get a job ASAP, and to get them the biggest salaries possible.

This is the promise that Lambda School came to market with in 2016. Since then, General Assembly and most of the other coding bootcamps have also begun to offer ISAs. They’re a great innovation, and help many students afford education they couldn’t otherwise afford.

But they’re not a one-way ticket to business success.

First of all, they’ve been widely copied. It’s a financing mechanism, not a moat. If your competitors are able to align incentives in the same way as you, then you have no comparative advantage. In order to constitute a sustainable competitive advantage, there would need to be some reason why offering ISAs at scale would make the experience better or cheaper for other students.

But, in reality, education is an industry that’s averse to scale. The best brands are the most selective, and by definition can’t be the largest. The largest brands can’t be as selective, and by definition can’t be the best.

Second, no matter how aligned the school is with the student, there needs to be an employer on the other end who wants to hire junior software engineers. Unfortunately, that demand is not growing as fast as the supply is. The hard part about running a bootcamp isn’t attracting students — it’s getting them hired.

About a month ago, New York Magazine published an article claiming Lambda School’s real placement rate was 50%. That’s much worse than what their website claimed at the time, that “86% of graduates are hired within 6 months and make over $50k a year.”

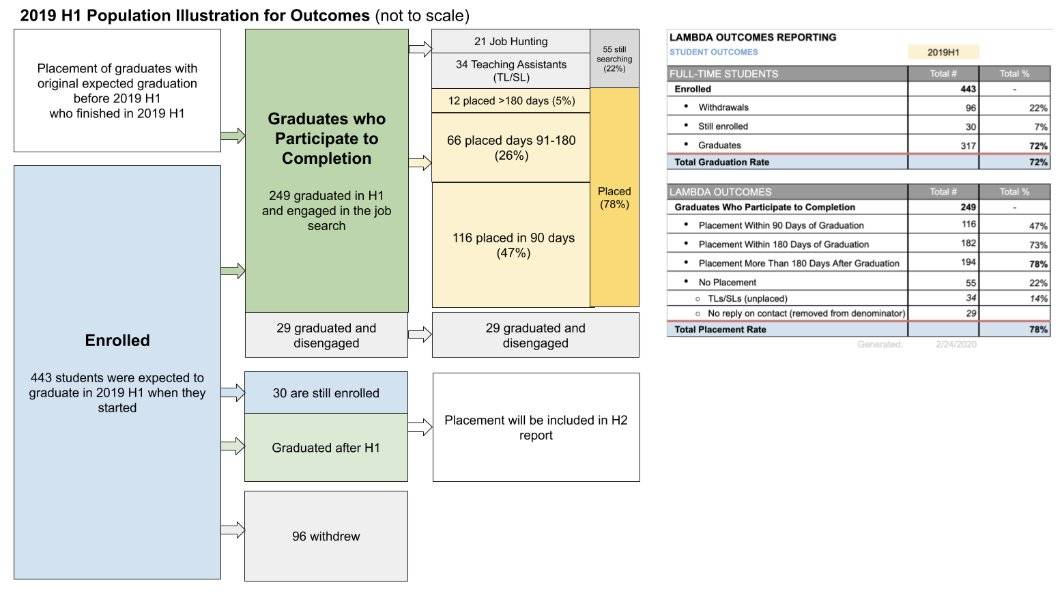

This prompted Lambda School’s CEO Austen Allred to share a graphic on Twitter, which breaks down their placement rates based on students graduating in the first half of 2019.

(If you don’t want, you don’t have to parse the whole thing. It’s complicated, and I explain the gist of it below.)

Using this graphic, they argue their real placement rate is actually 78%. The 50% number, they said, was what you get when you count all students who enrolled, not just those that made it to graduation. Many Lambda supporters took this to be a perfect refutation. Jason Calacanis recorded a podcast with Allred, and said “this was a slam piece that was ridiculous.”

The truth is not so rosy. There are a couple of badly misleading things about the 78% number.

First, it includes people who took more than 6 months to get hired. That’s not an apples-to-apples comparison with the original 86% number. If you only look at people within 6 months, you get 73%. Also, they don’t say whether “placed” includes people making less than $50k or people working in non-technical jobs. Right off the bat, it feels like they might be trying to decieve us.

Second, they’re only looking at a placement rate of “graduates who participate to completion.” Apparently 11% of people who make it all the way through a six month course and graduate aren’t counted. Lambda says they “disengaged,” but doesn’t define what that means. If they hadn’t fudged the 78% number, I’d be more inclined to trust them, but now I’m not so sure!

Third, there are several boxes in the diagram with missing numbers, and the way they’re arranged makes it impossible to calculate some important numbers. For example, if you want to know what percent of the 443 students who enrolled have gotten jobs so far, I can’t tell you. I can tell you that 194 people who graduated in H1 2019 got jobs, but Lambda is including previous cohorts in that number (the top left box). It’s definitely lower than 44% (because 194 / 443 = 43.7%) but how much lower? We do not know.

The bottom line is: despite their aligned incentive structure, less than half of students who enter Lambda school get jobs. No matter what way you slice it, that’s a big problem.

What can we learn from this?

It helps to take a broader view of the alignment hypothesis: in order to grow quickly, a business’s incentives need to be aligned with not just their customers, but all other important players in their value chain. And in Lambda School’s market, the employer is clearly the most important partner.

To be really aligned with employer’s needs would perhaps mean developing mid-level engineers into senior engineers, or turning engineers into engineering managers. These are the more pressing problems for every software company I’ve worked at, because a senior engineer is often 10-20x more productive than a junior engineer, and management is always a challenge.

But focusing on these problems would do nothing to help new/aspiring engineers. And it’s not a slam dunk as a venture-backed startup, because there’s a dramatically smaller pool of potential students. So it’s not likely that we’ll see Lambda, GA, or other venture-backed coding bootcamps focus there.

This brings us to the next complication of the alignment hypothesis: sometimes you have multiple stakeholders that want different things. (Jesse called this a “double bind” in our interview.)

Venture capitalists need Lambda School to achieve a certain type of outcome in order to consider it a “win.” This desire, however, exists in tension with what Lambda’s students and employers want. It doesn’t mean Lambda is doomed. They might be able to solve it. I hope they do! But when you’re balancing the needs of various stakeholders that don’t line up, it can be really hard to strike the right balance.

This “multiple stakeholder” complication is also what explains the recent controversy over Lambda School “selling” their ISAs to hedge funds. Many argued that this weakened their incentive to help students get jobs.

(I think this concern is a bit overstated, because they can’t sell them for long if they turn out to be worth nothing. And as it turns out, Lambda isn’t selling them outright, but instead has special terms that keep their short-term incentives fairly well aligned with students.)

But, to the extent that it’s an issue, it’s caused by the desire for fast growth. You can only admit so many students if you’re paying for their education with your own cash up front. If the cash comes from previous cohorts of students, you’re not going to be able to grow very quickly. Even though the most aligned position for students might be for Lambda to finance everything off their balance sheet, it’s certainly not the most aligned thing for Lambda’s shareholders.

The point of this section isn’t to criticize Lambda School. It’s also not to predict their imminent demise. They seem to be a good company that’s making mostly good decisions. Instead, the point is to illustrate how complicated things can get in the real world when you’re negotiating between three different parties — students, employers, and shareholders — to align everyone’s incentives.

Sometimes you have to do the best you can and fumble your way through obstacles as they arise.

Alright! So far we've covered how alignment doesn't promise fast timelines, and how alignment can get complicated when there are multiple stakeholders involved. Next, let’s look at how the trend towards alignment has transformed the media industry.

Subscriptions are better than ads, but they’re not 100% unproblematic

Sometime around the 2016 election, media commentators became increasingly focused on the ad-based business model as a source of trouble.

The idea is that advertising incentivizes publishers to get readers to merely click — rather than actually read and enjoy — an article. Subscriptions were thought to be the solution, because they required readers to part with their money. This ensures publications create content that readers truly value.

The New York Times led the shift away from ads when they announced in 2015 that their goal was to double their digital revenue by 2020 (which, by the way, they hit!), and that their main focus was subscriptions.

After that, things started happening fast.

In 2016, The Athletic launched their subscription sports writing bundle in Chicago. Patreon raised a big Series B round from Thrive Capital, and began to grow beyond its YouTube roots.

In 2017, Medium pivoted to subscriptions, and Substack (my former employer) launched with the goal of “accelerating the advent of a new golden age for publishing.” After that, platforms like Supporting Cast and Glow launched, trying to bring subscription publishing to the podcast world.

We’re still living through the subscription boom. It already seems to be a big improvement over the advertising-driven model of years past, at least in my personal experience. But it’s not a 100% pure win for consumers, let alone democracy. There are positives and negatives.

First, let’s consider the argument that subscriptions will lead to less sensationalism and more rational discourse. It makes sense at first blush, because nobody wants to pay for clickbait, but when you dig deeper you discover real problems with the argument.

People pull out their wallets for writers who help them understand topics they care deeply about. So it’s the writer’s job to get people to care deeply. Sensationalism does the trick pretty well. You just have to be better than writing a clickbait headline, and tell a soaring story that pays off in a bigger way.

Case in point: after he got kicked out of Fox News, Glenn Beck started one of the bigger independent subscription businesses on the internet.

Political content aside, subscriptions can do plenty of damage when applied to other topics, too. It’s not hard to find “get rich quick” schemes featuring shallow platitudes or scummy trading ideas. For every legitimate business publication, there are probably three to four scams.

Connecting all this back to “incentive alignment” — the general lesson here is that sometimes what customers want isn’t what they need. I’m extremely careful to tell anyone they don’t know what’s good for them, but if you zoom out and squint at society, it’s clear that all sorts of businesses exist as a sort of parasite on their customers. Food, entertainment, cigarettes, fashion, auto — there’s a good argument to be made that many businesses in these industries actually harm their customers.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that subscriptions are worse than ads. As you might expect, I actually think they’re better! The point is that reality is messy. Just because you have a subscription business instead of an ads business doesn’t automatically make a more virtuous company.

What can we learn here? Never let your enthusiasm for your model delude you into thinking you’re exempt from dealing with tough trade-offs. (I know I’m not!)

In fact, sometimes when you have a less aligned business model, and you’re super aware of it, you can actually end up in a better place than those who think their model takes care of any moral complications.

For example, I found the tension inherent in the advertising model to be a productive force during my time at Gimlet Media. Everybody knew there were problems that could come up if we didn’t keep an eye on it. And so I think we did a better job managing those problems than, say, the NYT is doing managing the potential problems with their subscription model right now. Of course, I can’t know for certain. But I don’t get the sense that there’s a lot of awareness about the tribal problems the subscription model can create. At least no one seems to be talking about it publicly.

Conclusion: why virtue matters

To recap:

- Incentive alignment is a good thing, and if your business’s incentive structure is more aligned with customers and other important players in your value chain, you’re likely to do better than a competitor that is less aligned.

- That being said, it still might take a long time. Warby Parker has been around for 10 years and is still just 3% of the size of their main competitor.

- Also, it gets hard when you have to deal with multiple stakeholders and their incentives may be irreconcilable. Lambda School is going through this now, trying to attract students, get employers to hire them, and make their shareholders happy.

- Finally, even if you do align your incentives with your customers, that doesn’t automatically give you the moral high ground. There’s often a difference between what people want and what people need. With subscription media, it’s rarely talked about, but there are many ways that it can stray from the truth and lead to even further fragmented tribalism.

So, what can you do to apply this at work tomorrow? The most important thing is to notice if you feel yourself or others slipping into a “silver bullet” mindset. There’s never just one thing that matters. Big wins come from managing a lot of complicated forces (as illustrated in the examples above) with grace.

One exercise that helps is to write out how your company’s incentives may be aligned or misaligned with customers. Then, try and complicate it. Ask yourself how long it might take for the alignment to pay off, whether there are other important participants in your value chain that you’re forgetting, and whether you’re aligned with what people want, or what they need.

Do that, and you’re in a good position to notice important details that others may miss. If you do, you’ll have a much better chance at success than before.

Before we go, one last philosophical note:

The limits of “incentive alignment” we explore here are a reflection of a more fundamental debate that’s been happening amongst political philosophers for centuries. The question: is modern liberalism good? (Here, using “liberal” in the classic meaning of democracy and capitalism, not in the modern American sense as a synonym for “progressive.”)

Democracy and capitalism are based on incentives. Our system of government is designed to check “ambition against ambition,” and our system of capitalism is designed to harness self-interest in order to create shared societal value. Does this combo produce the best possible society? On their own, I think not.

The truth is that no system of incentive alignment can ever take you all the way. At some level you have to have virtue. Individuals have to take actions that consider the well-being of a broader whole. We have to opt out of total optimization of a simple metric, in favor of more holistic human judgment.

Is it easy? No. Can you enforce it with a law? No. Culture changes more subtly, through story and belief. Ours seems to be breaking down. It feels clear that we need new stories.

That’s why I think this is worth talking about.

Did you like this? Let me know! Click the purple “Like & Comment” button.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!