If you want to get good at a game, it helps to understand a bit about the nature of that game.

Obvious, right? But in his seminal book, Competitive Strategy, Michael Porter argues the game of business is often very poorly understood—even by those in positions of great power.

Everybody gets that, at some level, the idea of business is to generate profits, and that businesses are constrained in their ability to do so by the existence of other businesses (competition.) But ask someone to go one level deeper into how the competitive process works, and you quickly descend into platitudes and confusion.

There are two main types:

The first are the “adversarialists,” who think competition is everything. They’re focused on being the best, and trouncing rivals. Remember Google+? When it launched, Mark Zuckerberg put up posters declaring “Carthago delanda est” (Carthage must be destroyed) and asked all Facebook employees to work late, and limit paid leave. This is typical of the “adversarialist” attitude towards competition. They assume business, like war, is fought in head-on battles, and in order to win, you need to be bigger, meaner, and tougher than your adversary.

The second camp subscribes to the opposite belief, and denies that competition exists at all. Let’s call them “friendlies.” They think of business as a sort of third-grade art class, where everybody’s just trying to do their best to manifest their unique potential, and can achieve excellence completely independently of each other. “Ignore your competition,” they say.

In reality, business isn’t like war or art exhibitions. It’s something in between.

Unlike war, competition doesn’t have to be head on. Plenty of managers think that’s the only option, so they act as if business were war, but Porter argues that that’s more optional than you’d think. Human needs are nuanced, and there’s almost always room to find a unique position in the market, rather than fight over one somebody else already occupies. When businesses engage in ruthless head-on competition, it tends to center on pricing, and erodes profits for everyone involved.

So business isn’t like war. (Or, at least, it doesn’t have to be!) But it’s not exactly sunshine and rainbows, either! Unlike third-grade art class, where every stick figure gets a prize, business involves both success and failure. In markets, people have limited resources, and only part with them if necessary. If somebody else is selling drawings for less, or is able to make special drawings, somehow, and charge a higher price, you could find yourself without a prize. No matter how hard you worked.

So we’ve ruled out war and art class as good metaphors to explain how competition works. But how does it work?

If you want to get good at a game, it helps to understand a bit about the nature of that game.

Obvious, right? But in his seminal book, Competitive Strategy, Michael Porter argues the game of business is often very poorly understood—even by those in positions of great power.

Everybody gets that, at some level, the idea of business is to generate profits, and that businesses are constrained in their ability to do so by the existence of other businesses (competition.) But ask someone to go one level deeper into how the competitive process works, and you quickly descend into platitudes and confusion.

There are two main types:

The first are the “adversarialists,” who think competition is everything. They’re focused on being the best, and trouncing rivals. Remember Google+? When it launched, Mark Zuckerberg put up posters declaring “Carthago delanda est” (Carthage must be destroyed) and asked all Facebook employees to work late, and limit paid leave. This is typical of the “adversarialist” attitude towards competition. They assume business, like war, is fought in head-on battles, and in order to win, you need to be bigger, meaner, and tougher than your adversary.

The second camp subscribes to the opposite belief, and denies that competition exists at all. Let’s call them “friendlies.” They think of business as a sort of third-grade art class, where everybody’s just trying to do their best to manifest their unique potential, and can achieve excellence completely independently of each other. “Ignore your competition,” they say.

In reality, business isn’t like war or art exhibitions. It’s something in between.

Unlike war, competition doesn’t have to be head on. Plenty of managers think that’s the only option, so they act as if business were war, but Porter argues that that’s more optional than you’d think. Human needs are nuanced, and there’s almost always room to find a unique position in the market, rather than fight over one somebody else already occupies. When businesses engage in ruthless head-on competition, it tends to center on pricing, and erodes profits for everyone involved.

So business isn’t like war. (Or, at least, it doesn’t have to be!) But it’s not exactly sunshine and rainbows, either! Unlike third-grade art class, where every stick figure gets a prize, business involves both success and failure. In markets, people have limited resources, and only part with them if necessary. If somebody else is selling drawings for less, or is able to make special drawings, somehow, and charge a higher price, you could find yourself without a prize. No matter how hard you worked.

So we’ve ruled out war and art class as good metaphors to explain how competition works. But how does it work?

Michael Porter defines competition in business as the struggle to attain a profitable, unique position in the market. Instead of “competing to be the best,” you should “compete to be unique.”

We don’t get a juicy metaphor like “blue ocean” (or “war,” or “art exhibition”) from Porter. His style is more academic—maybe something he learned in his Economics PhD. But I did find one from Al and Laura Ries (known for their work on Positioning) that fits perfectly: Evolution.

Markets as ecosystems

In the beginning, there were very few species on the planet. Over time, in order to adapt to diverse environments, species forked and multiplied. Life became more complex as it grew.

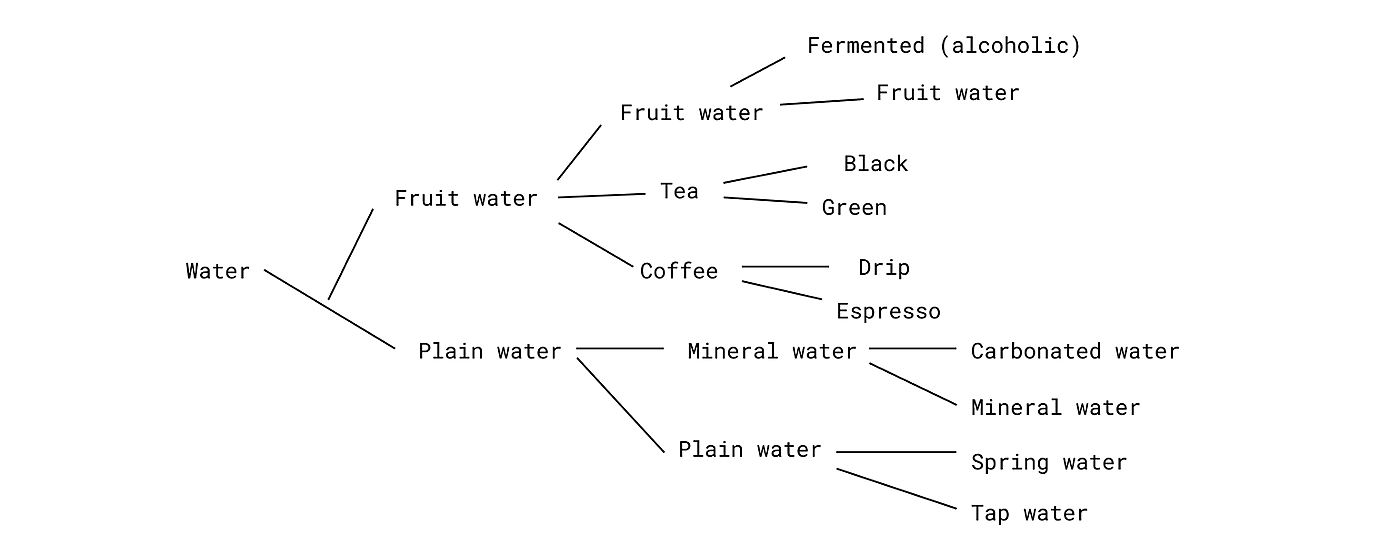

The same thing happens with products. Take the basic human need for hydration. Over time, the options have multiplied, and each option gets increasingly specific:

Now, if you take a walk down the beverage aisle of a grocery store, you’ll see hundreds of products, and there are millions more waiting for you, out there in the world.

This same thing has happened for every product category. Whether we’re talking computers, or soap, or transportation, or reading material, the pattern repeats itself over and over: the set of options grows, and each option gets more specific.

Al and Laura Ries aren’t the only people who think evolution is a good metaphor for business. Charlie Munger agrees with them, too:

"I find it quite useful to think of a free market economy—or partly free market economy—as a sort of equivalent of an ecosystem. Just as animals flourish in niches, people who specialize in some narrow niche can do very well." — Poor Charlie’s Almanack, pg 54

But wait, isn’t this obvious?

In the startup world, the idea that strategy is about creating new things that are different from what already exists sounds absurdly obvious, but when Porter first started publishing these ideas in the 70’s and 80’s, most businesses tended to flock together like sheep. And in many industries, they still do.

People put a lot of emphasis on operational effectiveness. They think if you carry out the same strategy as someone else, but with more vim and vigor, then you can win. There’s a grain of truth there: a unique strategy is worth nothing without great execution, and execution is usually the hard part. But, if your plan is to energetically pursue the same strategy as everyone else, it won’t lead to riches.

Ultimately, only one company can profitably occupy any given market position.

So, what does this mean for managers trying to understand the nature of competition? It’s pretty basic, but true, advice:

-

As a manager of an existing business, your job is to fortify your niche in the ecosystem, so that nobody is tempted to take it.

- As an entrepreneur creating a new business, your job is to create the next layer of complexity. Look for what is newly possible, or newly revealed to be possible.

Above all, recognize that competition in business doesn’t have to be like war, but it’s not as friendly like an art class, either.

Instead, competition is defined by the struggle to be unique.

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!