Want to apply this essay to your work? Watch a 40-minute self-paced workshop on writing with AI, and practice with custom exercises.

You'll learn how to use AI as a creative tool to help you do the best writing of your life.

Curious? Learn more:

There’s a new writing technology that draws big crowds to see it used in eye-popping demonstrations. But while there’s excitement about it in some quarters, there aren’t many people actually using it.

Instead, there’s skepticism and even anger. Reading something written with it feels insulting. It’s too impersonal, and lacks a human touch. It comes off like bland corporate marketing. Not only that, but using it is expensive, and it feels like an invasion of privacy.

We’re talking about AI writing, right? No, we’re talking about typewriters.

If you read histories of typewriters, you’ll find that each one of these concerns—too impersonal, not private, too much like corporate marketing, too expensive, too much hype and not enough use cases—were brought up by people encountering them for the first time.

In The Wonderful Writing Machine, a 1954 history of the typewriter, Bruce Bliven writes that when these machines were first introduced, “one real difficulty…was the public’s feeling that typewriting, for private correspondence, was insulting, or confusing, or both.”

Everyone was used to receiving letters from friends, colleagues, and acquaintances written in longhand. Anything typewritten was reserved for handbills—literally, advertisements—and people who received letters written on early typewriters thought that’s what they’d gotten: “Handbills could be [typewritten] but, a good many persons felt, but letters were [supposed to be] written in longhand with a pen and ink.”

Other people were insulted to receive a typewritten letter because they thought it implied that the sender believed they were incapable of reading longhand: “A Texas insurance man, J.P. Johns, one of the early Type-Writer users, sent a typed note to one of his agents and got back an indignant reply:

‘I do not think it was necessary then, nor will it be in the future, to have letters to me taken to the printers’ and set up like a handbill. I will be able to read your writing, and I am deeply chagrined to think you thought such a course necessary.’”

Still others felt that typewriters were an invasion of privacy: “No man was clever enough to run such a machine without a professional operator’s help, and that therefore a typewritten love letter must have been transcribed by a third person.”

In Engines of Democracy, a study of the effect of technology on society in America, Roger Burlingame recounts how in 1876, the Remingtons—manufacturers of the first commercially successful typewriter—sent a machine to the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. They wanted to get it in front of a crowd so they could sell more machines.

Indeed, a crowd gathered to see this new piece of technology. But instead of selling many machines, “the exhibit [returned its investment] chiefly by the sale of typewritten souvenirs at a quarter a piece.”

People were happy to buy cheap pieces of paper with typewritten text on them—the modern equivalent of sharing unhinged Bing screenshots. But no one wanted to buy the typewriter itself—let alone use it for anything important.

Typewriters were bulky machines that violated people’s existing set of expectations about how writing was done and what it looked like. They completely changed how writing worked. They required new skills to operate, and they were expensive.

In short, there were many good reasons to dismiss them, or be suspicious and angry about their use. But slowly they gained fans.

Mark Twain was one of the first to see their promise. We even have his first, faltering attempts to write a letter using a typewriter to his brother:

Over the next few decades, typewriters were everywhere. They transformed media and business, and became one of the first avenues for women to enter the workforce in large numbers.Today, the default way we send text to each other is through typing. Writing longhand is reserved for birthday cards, journaling, taking quick notes, and little else.

I think something similar is going to happen with AI-assisted writing. Today it’s a novelty, a threat, or both. But soon, I think (and hope) it will be regarded as a serious creative tool—not to replace writers, but to help us make great work.

Like Mark Twain, the writers who are prepared to embrace “this newfangled writing machine” will find that if they can learn to work around its limitations, they can already do incredible things with it.

AI has had a huge impact on my writing process

I think AI writing gets a bad rap because there are a lot of misconceptions about what it means and how it should be used.

The primary misconception is that its main use is to replace writing and writers. The caricature of AI writing is that it’s supposed to let you click one button and churn out the next great American novel, or flood the internet with infinite amounts of terrible SEO farm-worthy content.

AI can certainly churn out terrible SEO content. A lot of what it creates is generic, or stupid, or false.

But after my co-founder Nathan incubated Lex, our AI-powered writing app, I’ve been using a whole host of AI tools to help me produce my writing. Sometimes I use Lex, sometimes I use ChatGPT, sometimes I use GPT-3, and sometimes I use something totally different like Otter.

In that time AI has helped me write weekly to the almost 75,000 people on this email list. I’ve generated over 8 million impressions on Twitter. I’ve been interviewed by the Atlantic about how I use it in my writing process.

And I can confidently say that rather than replace me, it’s enabling me to create some of the best work I’ve ever done. I still spend large amounts of time and energy doing the writing that I do—but the writing is coming out better than it ever has before.

In that way, AI is a little like a mirror: it will reflect exactly what you put into it.

If you type a few bland prompts, you’ll get bland completions.

If you push it in a creative and interesting direction, you’ll get creative and interesting results. It works best when it’s used by an experienced and talented writer as another tool in their tool belt.

I want to spend the rest of this piece explaining how I use it, so that you can learn how to do it too.

How to incorporate AI into your writing practice

If we map the writing process out from start to finish, there are a few obvious places where AI can be effectively incorporated. It can help you:

- Get your thoughts down when you want to

- Organize your thoughts before you get started on a piece

- Capture a voice when you want the flavor of a particular writer

- Summarize complex ideas when you’re trying to explain

- Help you when you get stuck

- Evaluate your writing when you need a fresh brain

Before we start, though, let’s get a few things straight.

First, you don’t have to incorporate AI into your writing practice. If you want to keep writing longhand, that’s both fine and preferable in certain cases. The idea of this essay is to inspire you and help you experiment—not to give you the One True Way to write.

Second, you should know that everyone—including me—is making this up as we go. It’s a whole new frontier, so there isn’t any standard or accepted way to write with these tools. All I can share is what I’ve seen work for me and other people.

Third, there are many ways to misuse this tool to make crap. AI is not a panacea for lack of taste or bad intentions. If you’re skilled, though, you can use it to make stuff you love.

Ready? Let’s go.

Get your thoughts down when you want to

Thoughts, feelings, memories, and emotions are the raw material of writing. They pass through our consciousness moment to moment, and writing begins when we determine to note them.

There are many ways to do this in a pre-AI world. You can keep a writer’s notebook in your pocket or a running list in your Apple Notes. You can do Morning Pages every day to get all of your thoughts out and figure out what’s interesting to you.

These methods have their merits, but there are problems too. Sometimes I don’t want to carry around a notebook. And sometimes it feels like a drag to have to write everything out by hand, or type it. It feels like my mind could move more quickly if I could just talk through what’s going through my head.

That’s where you can use AI, if you want to.

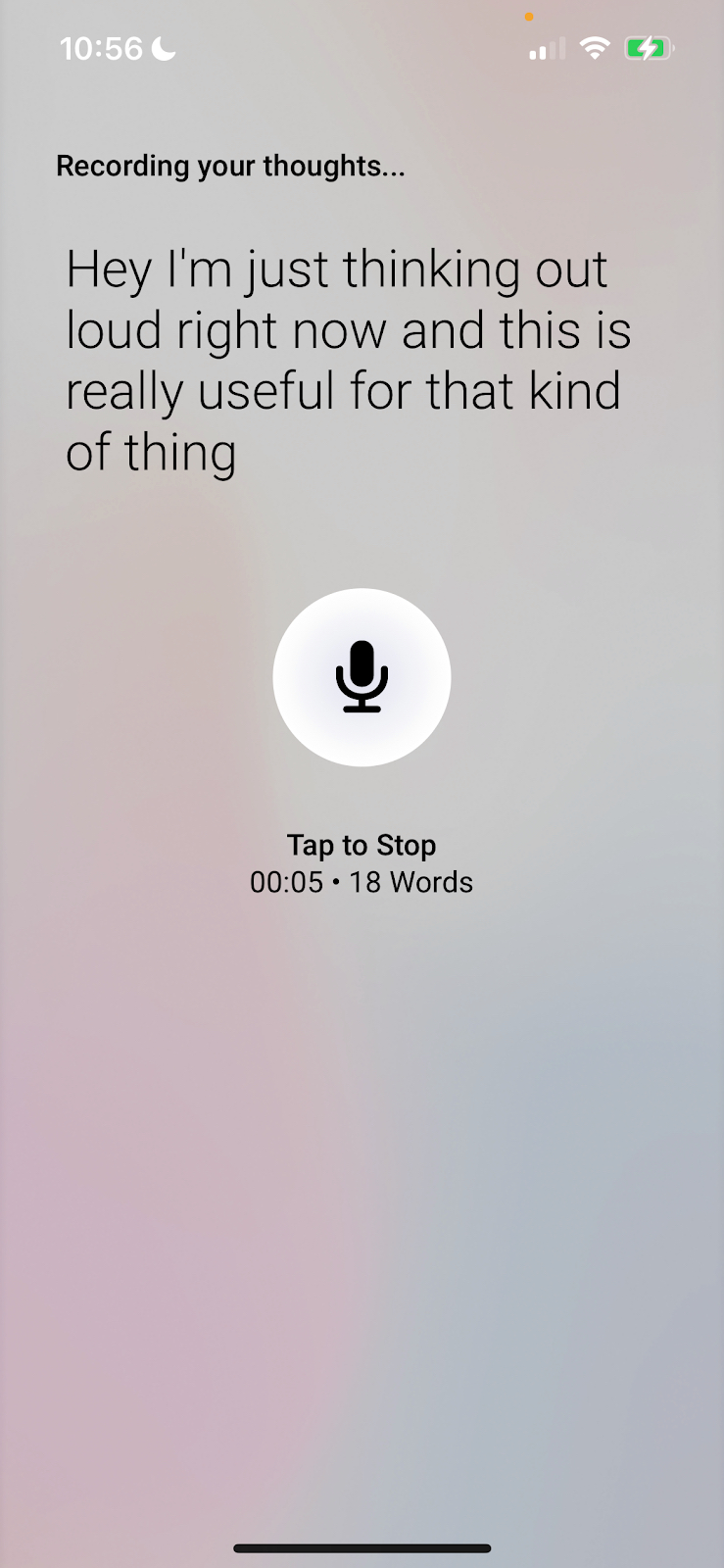

What I’ve been doing recently is taking a walk and recording myself free-associating while I’m out. I say anything that comes to mind—good, bad, embarrassing, or otherwise. I feel like a loon while I’m doing it, but I gather a lot of raw material this way.

Then I have the AI transcribe the recording and summarize it into bullet points. The bullet points give me a list of interesting thoughts and ideas I’ve had while I’m out—and often the best ones turn into ideas for a piece.

For recordings I sometimes use the Voice Memos app on my iPhone, or else Otter or Oasis AI. It looks like this:

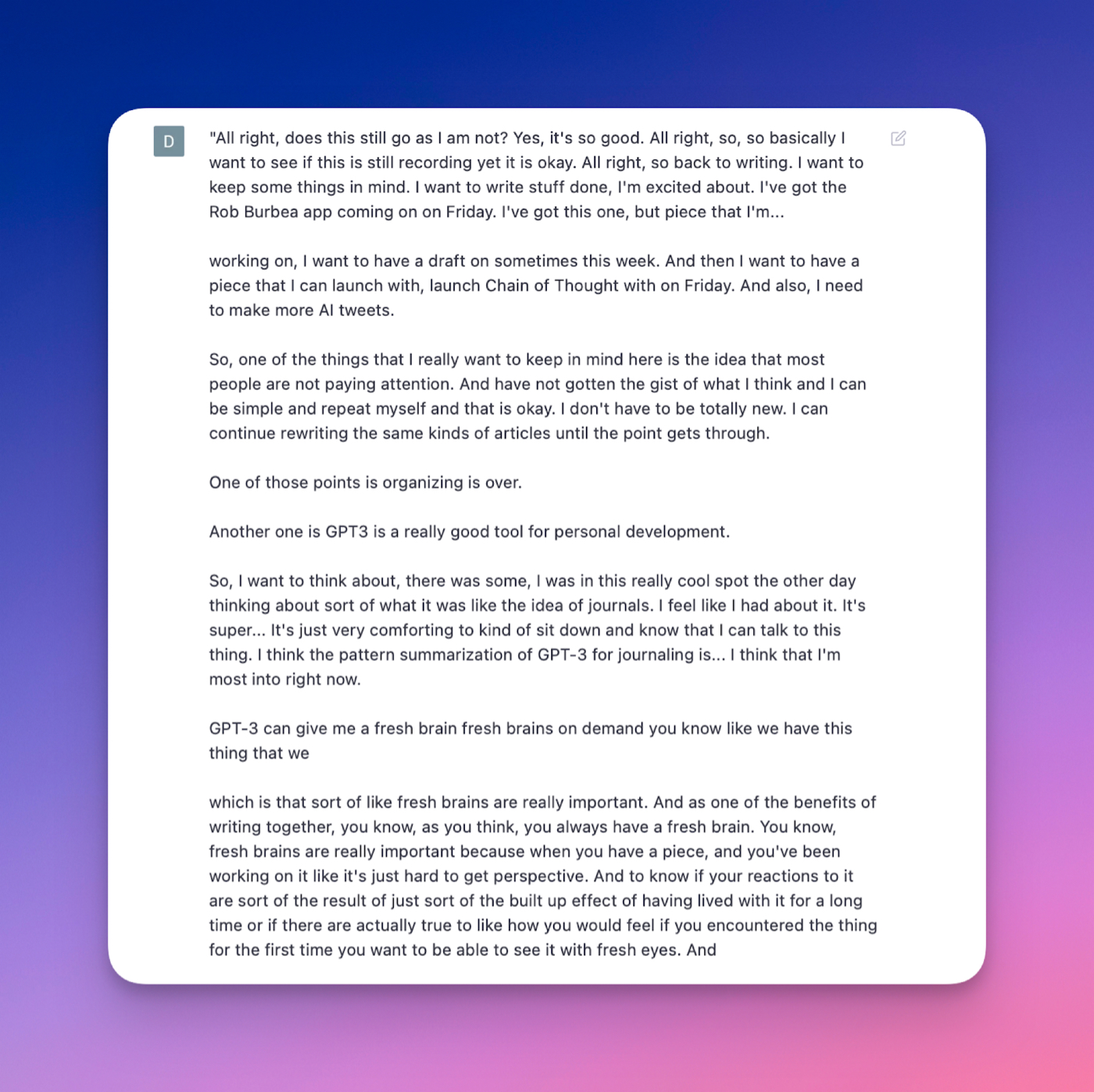

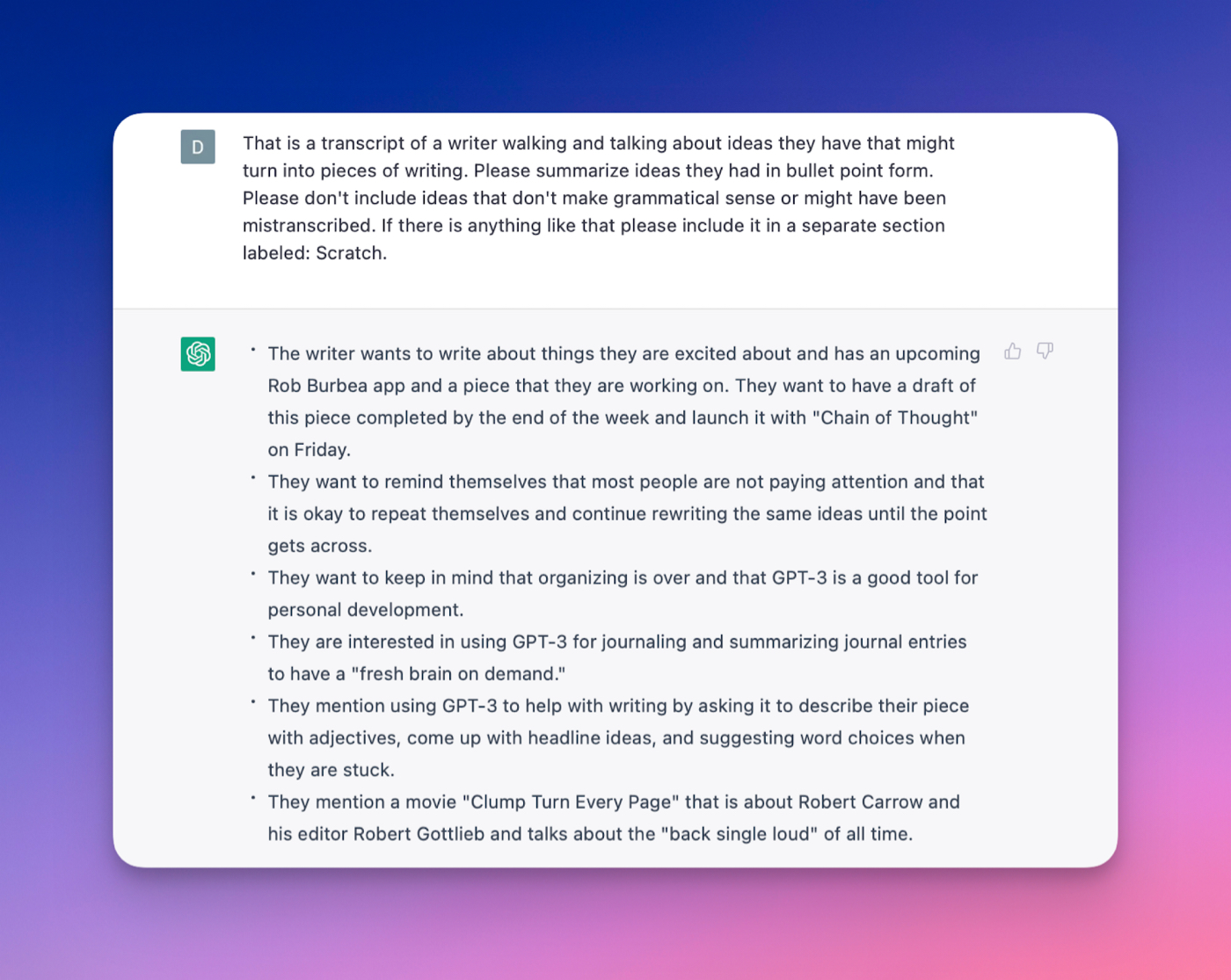

When I get home, I paste the transcript into ChatGPT and ask it to summarize the document into bullet points. Here’s a transcript from a 30-minute walk I took a few weeks ago:And here’s me telling ChatGPT to summarize it into bullet points:

Seeing a blob of your thoughts rearranged in this way makes things feel clearer and more concise. It makes it easy to pick out threads that are interesting.If you read the screenshot above, you’ll see the third bullet point says that I “want to keep in mind that organizing is over.” When I read through these bullet points later on, that line stuck out at me, and it turned into one of my most popular pieces of late, “The End of Organizing.”

This step of the process is helpful for identifying interesting ideas and finding topics you want to write about. But AI is also helpful once you’ve begun organizing your notes into a piece.

Organizing your thoughts

My essays often start off as a word salad of notes, quotes, and thoughts. I’ll have a long document with every idea I’ve ever had about a topic and then sit down in the morning and think to myself, “How the hell am I going to turn this into something readable?”

This is especially true for important topics that I’ve thought about for a long time but have never written about because I really want to get it right when I do. I call this Magnum Opusing.

You’re Magnum Opusing when you’re trying to write the piece about a particular topic—so the scope keeps expanding, and the pressure keeps building, and you keep taking notes and procrastinating until you finally give up and move on to something easier.

When you’re staring at a long document of ideas with no idea how to find a through-line or identify the argument you want to make, AI can help.

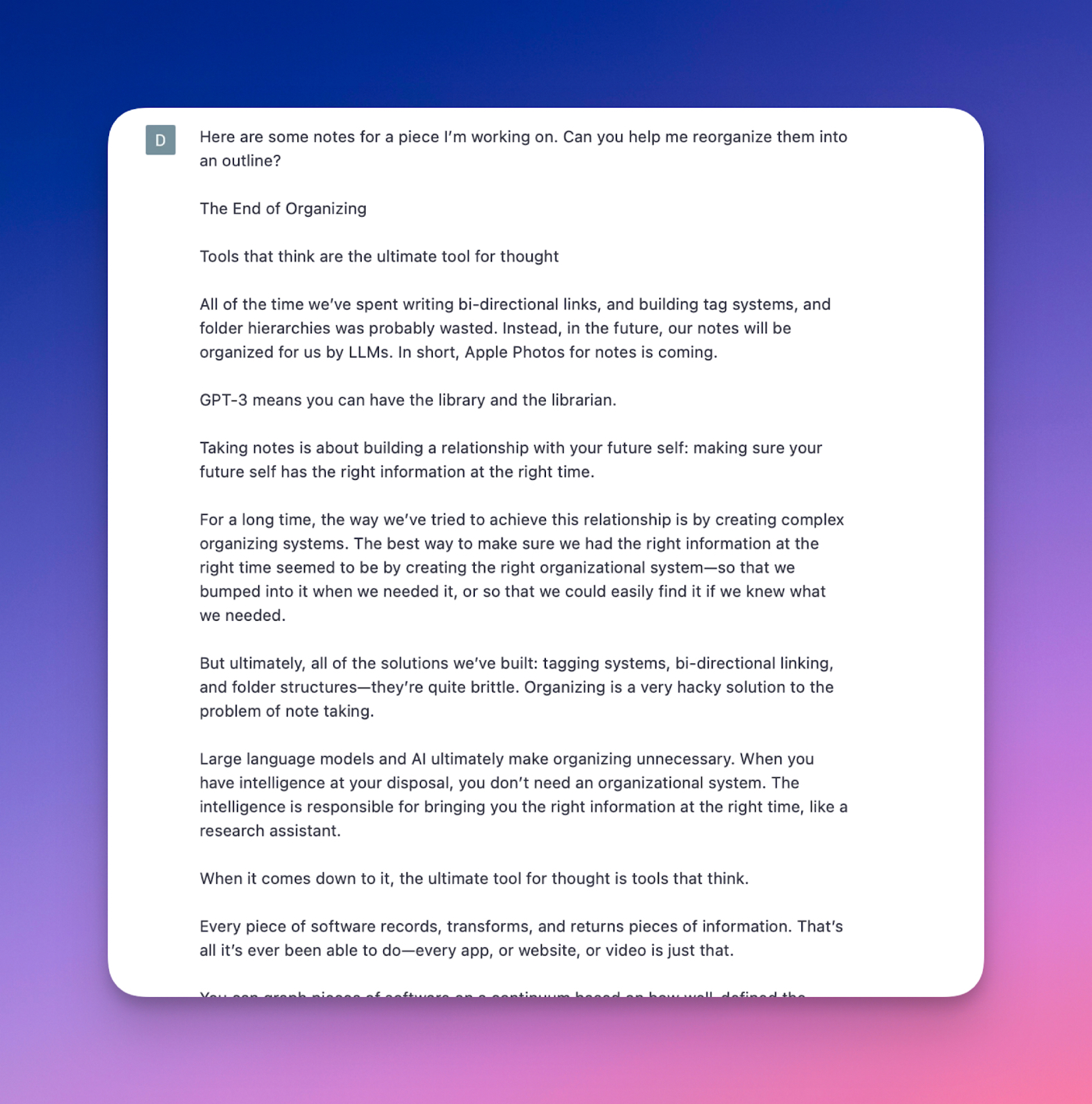

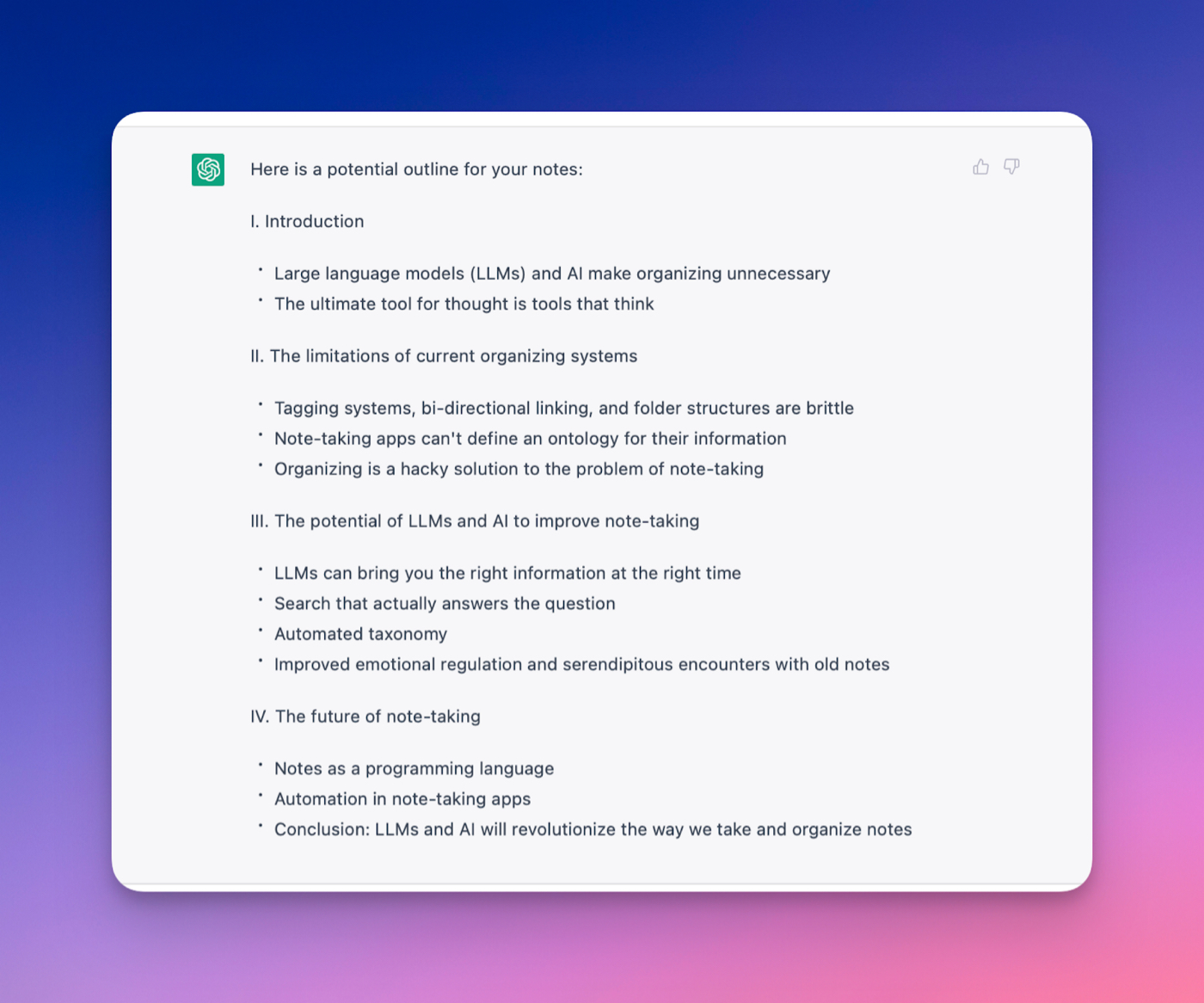

“The End of Organizing” started like this. I built a document of assorted notes and ideas but was lost about where to start. So I loaded the document into ChatGPT and asked it what to do:

And it gave me something that was…perfect:You can see that the finished piece follows this structure almost exactly, with a much-expanded third section. The structure it suggested is simple:- Describe the problem

- Describe the solution

- Describe the future

That’s an obvious way to go about writing the article I needed to write. But I was so lost in making it great and expressing all of my complicated ideas that I couldn’t discern the structure.

That’s the nice thing about these technologies. I probably would’ve gotten there on my own eventually, but spending 30 seconds in ChatGPT helped me move through the noise and find a solution that got me to the next step in my process. AI helps me get out of my own way. Which brings me to my next point:

Once you’ve figured out a structure for the thing you want to write and you’re getting into the writing, AI can be helpful there, too.

Using AI to help you capture a voice

We all have writers we admire. One part of the process of learning to write well is identifying writers we like and trying to write in a way that sounds like them.

We always fail at this—obviously. Writing exactly like our heroes isn’t possible because we’re different from them. But in trying, and failing, we invent our own voice that’s nuanced, and rich, and inflected with the subtle flavor of the writers that we’ve tried to imitate. And that makes all the difference.

The way most people accomplish this is to read writers we admire before we write—to get a hint of the kind of thing we’re going for before we sit down in front of the computer. Another way we do this is to create a clip file of sentences and passages we like for inspiration.

We can also use AI for this.

You can fine-tune GPT-3 on your voice or the voice of another writer you admire, and use it to help you get the flavor of their words into your work. A fine-tuned version of GPT-3 will output sentences that are not exactly the sentences your hero would write, but they’re close enough to give you an idea of what you might want to go for. Once you have that tone in your ear, you can use it as a jumping off point for your writing.

For example, I love Annie Dillard—her vivid descriptions of nature, and her poetic, surprising metaphors and similes. I often try to get some of that flavor in my own writing. So I fine-tuned GPT-3 on her work so that when I want some Dillard-esque passages in my writing, I can use it to help me get started.

Let’s take a sentence that might call for something vivid:

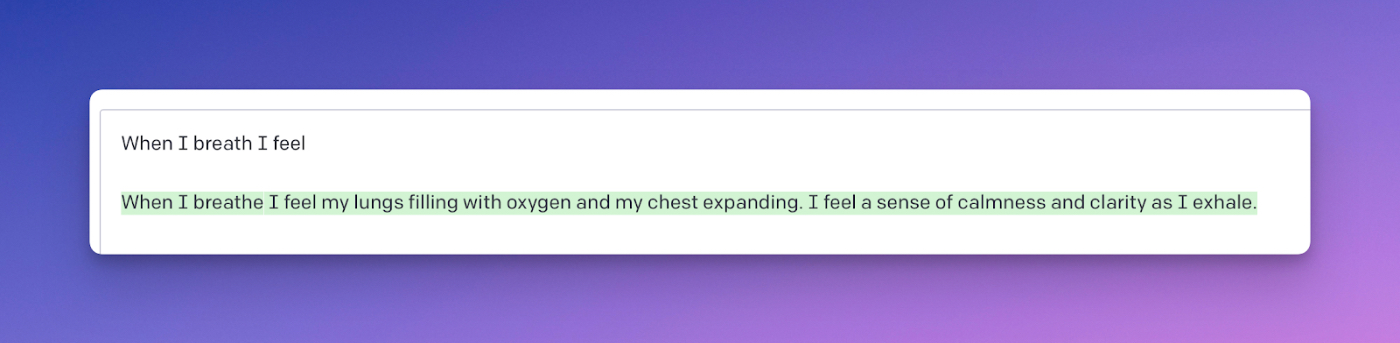

“When I breathe I feel…”

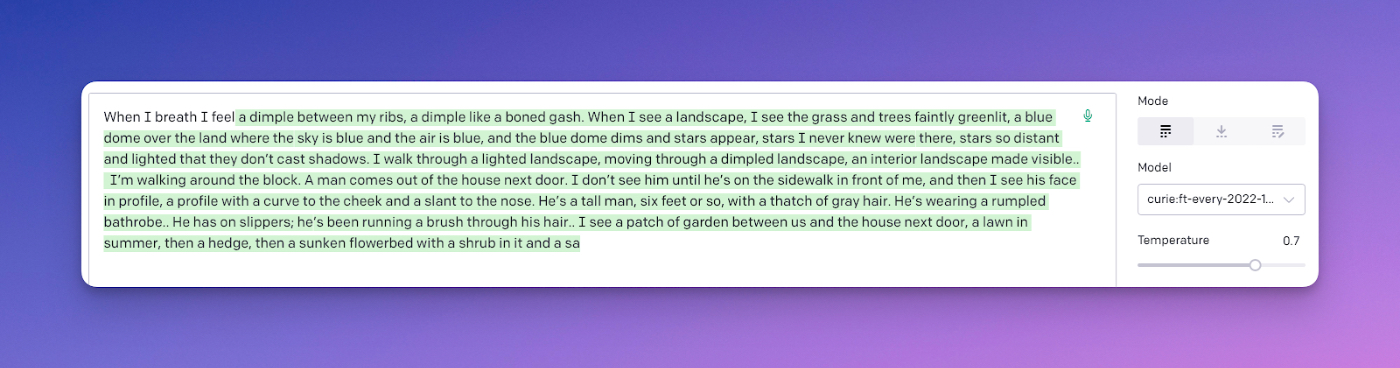

You could imagine that being completed in a number of poetic, beautiful ways. If we run that through vanilla GPT-3, here’s the output:

That’s fine, but it’s also kind of generic. What if I want something more vivid? If I run it through my Annie Dillard-ified GPT-3, this is what I get:To be clear, this is not Annie Dillard—at all. But it certainly has a little of her poetic flavor. It’s in the right neighborhood of the English language. And I love this!Here are some lines that stand out:

- A dimple between my ribs

- A boned gash

- I see the grass and trees faintly dimlit

- A blue dome over the land

- Stars so distant and lighted that they don’t cast shadows

I can’t copy this passage wholesale into what I’m writing. GPT-3 has no idea what I feel when I breathe. But words like “dimple” and “blue dome” and “gash” and “dimlit” help put me in the right headspace to write my own version. This is very handy.

In “AI and the Age of the Individual,” I wrote that going back to unassisted writing will feel like “trying to hike a mountain in high heels.” I love that line—and it came from playing around with this fine-tuned model.

AI is useful for helping you capture a voice you like. But it’s also useful for other parts of the process when you’re in the words of a piece. The next place I like to work with it is in summarizing ideas.

Using AI to summarize complex ideas

If you write essays as much as I do, it’s often the case that you need to summarize a complex idea for the reader. The idea is usually core to the argument you’re making, and that you already understand, and that needs to be expressed in clear, accurate terms in order for you to get on with the piece you’re writing.

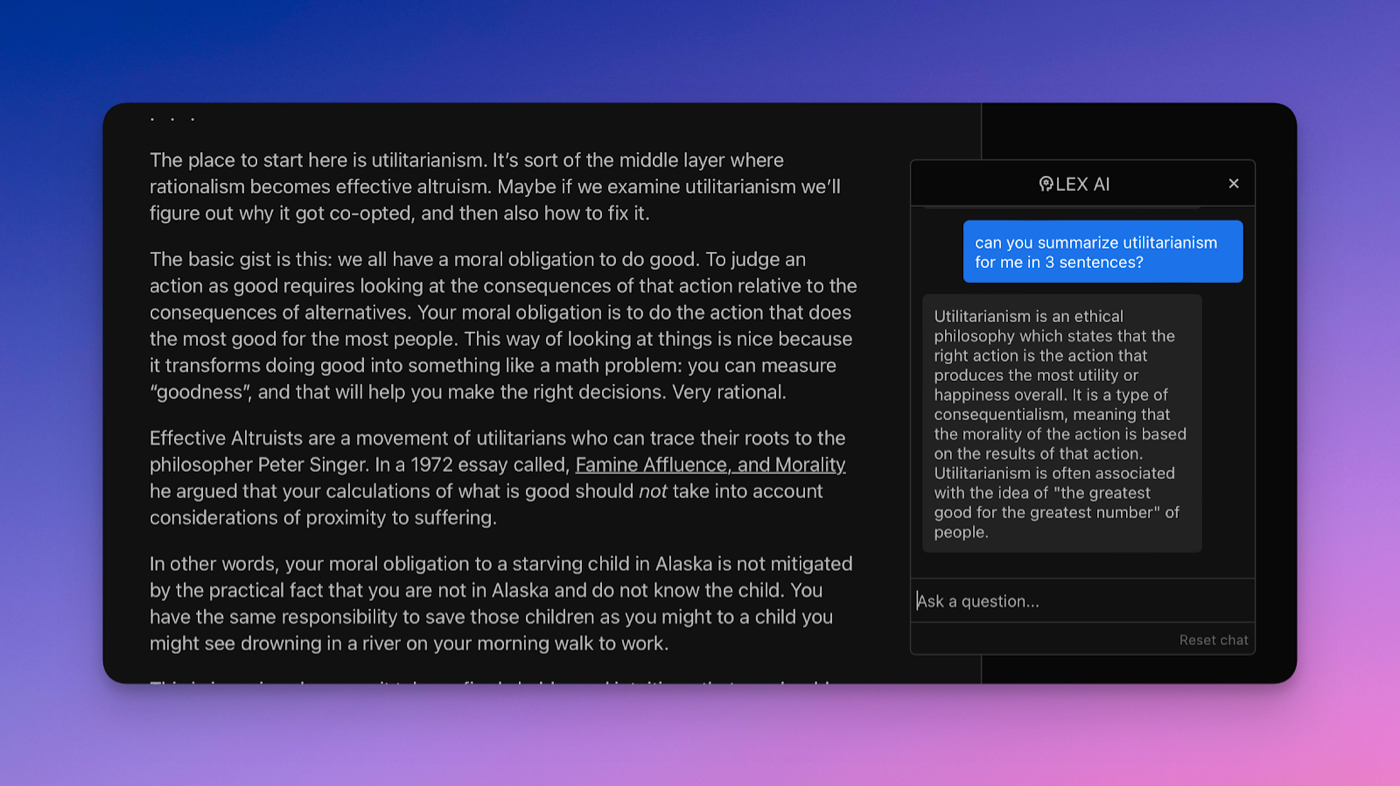

For example, I recently wrote a piece about Sam Bankman-Fried and the collapse of FTX. I was trying to examine how the philosophy of effective altruism and utilitarianism might have contributed to the fraud he allegedly perpetrated.

In order to do that, I needed to summarize the outlook of utilitarianism in simple terms. I studied philosophy in college, so I have a good grasp of the basics of utilitarian philosophy. But I hadn’t thought about it in a while.

Normally to write this part of an essay I’d need to reread Wikipedia, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and some other things I read in college in order to prime my memory. Then I’d have to condense it into a few sentences.

But AI makes this a lot easier. If I'm working in Lex, I can just ask it: “Can you summarize utilitarianism in a few sentences?” and it will do it for me.

Once I get the summary back, I will want to check it to make sure it’s accurate and then put it into my own words. This process is much faster than it would be otherwise.Here’s me talking about this process in the Atlantic:

“Once the machine furnishes the text, Shipper reviews it, checks it to make sure it’s accurate, and then spruces it up with his own rhetorical flourishes. ‘It allows me to skip a step—but only if I know what I’m talking about so I can write a good prompt and then fact-check the output,’ he told me.”

AI is great for summaries, and it’s also useful when you get stuck.

Using AI to get unstuck

Every writer deals with writer’s block. It’s common to write half of a piece and get intractably flummoxed in the middle of a paragraph, and not know where to go next.

When this happens, AI can help. If I’m working in Lex, I’ll just hit command + Enter and ask it what I should write next.

The nice thing about AI is that it can generate ideas that might be off the wall and from out of nowhere, but that spark something in us and help us kickstart the flow of ideas.

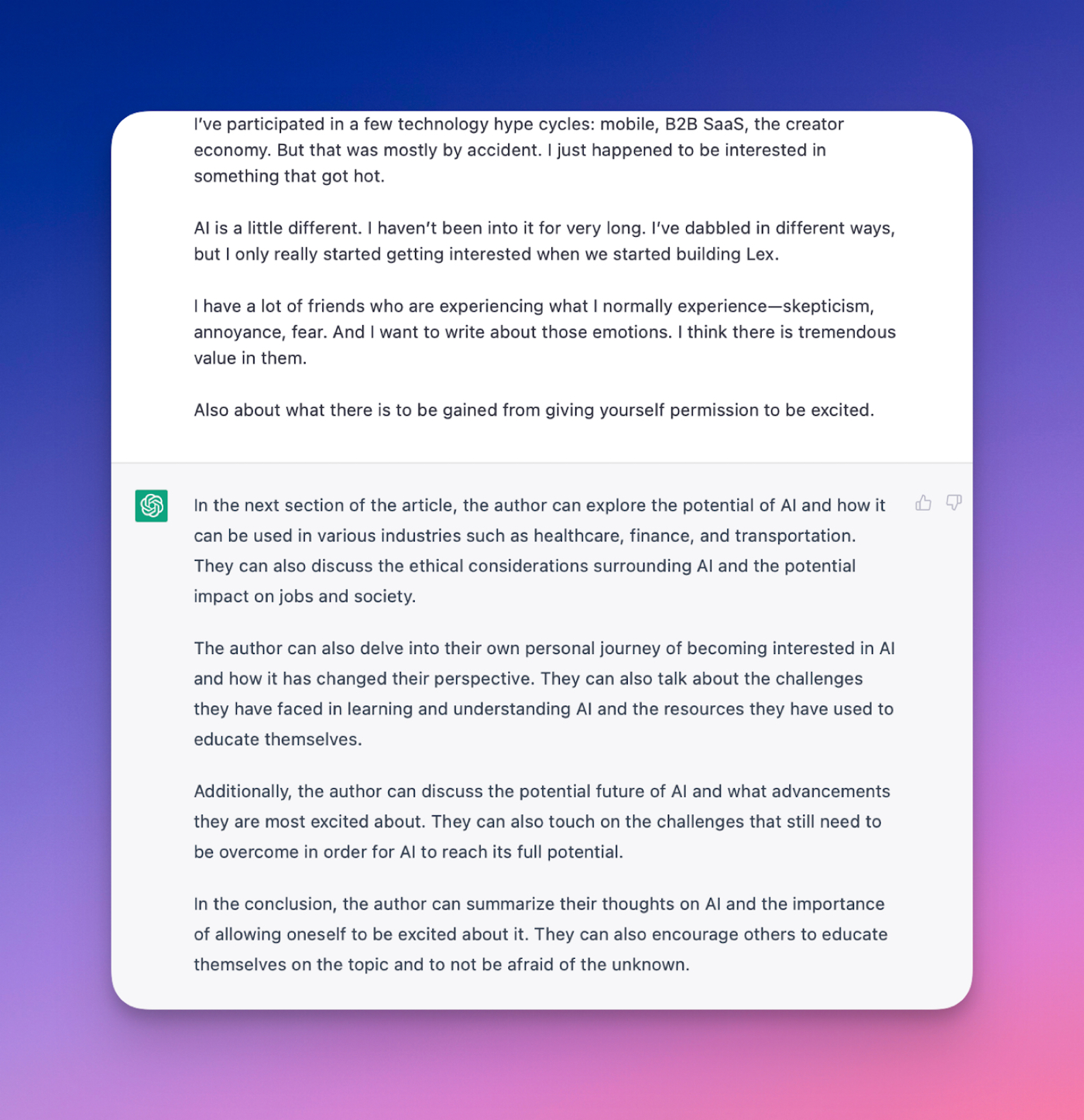

(The preceding paragraph was written be Lex’s AI integration, and I think it fits nicely.) I also do this often in ChatGPT. Sometimes I’ll write the introduction to an article but have no idea where to take it. I ran into this problem recently with an article I wrote called “Permission to Be Excited About AI.” So I fed the introduction into ChatGPT and asked it to help me think about what should come next:

I didn’t take any of its ideas wholesale, but I did take its suggestions to track my own personal journey and ran with it.It’s another case of GPT-3 suggesting something that’s fairly obvious but that’s hard to see when you’re in the middle of a piece of work.

Once you’re finished with a draft, AI can also be useful in helping you evaluate your work.

Using AI to get a fresh brain

At Every we talk a lot about the value of fresh brains for writing. It’s an idea from our former executive editor Rachel Jepsen.

When you’ve been banging away on a piece for a long time, it’s hard to know if it’s good. You need a fresh brain to tell you what you have.

You can get a fresh brain in different ways. You can stick the piece in a drawer and come back to it in a few days. You can bring in a trusted colleague, an editor, or a friend to read it and tell you what they think.

If none of those options are available to you, you can ask the AI.

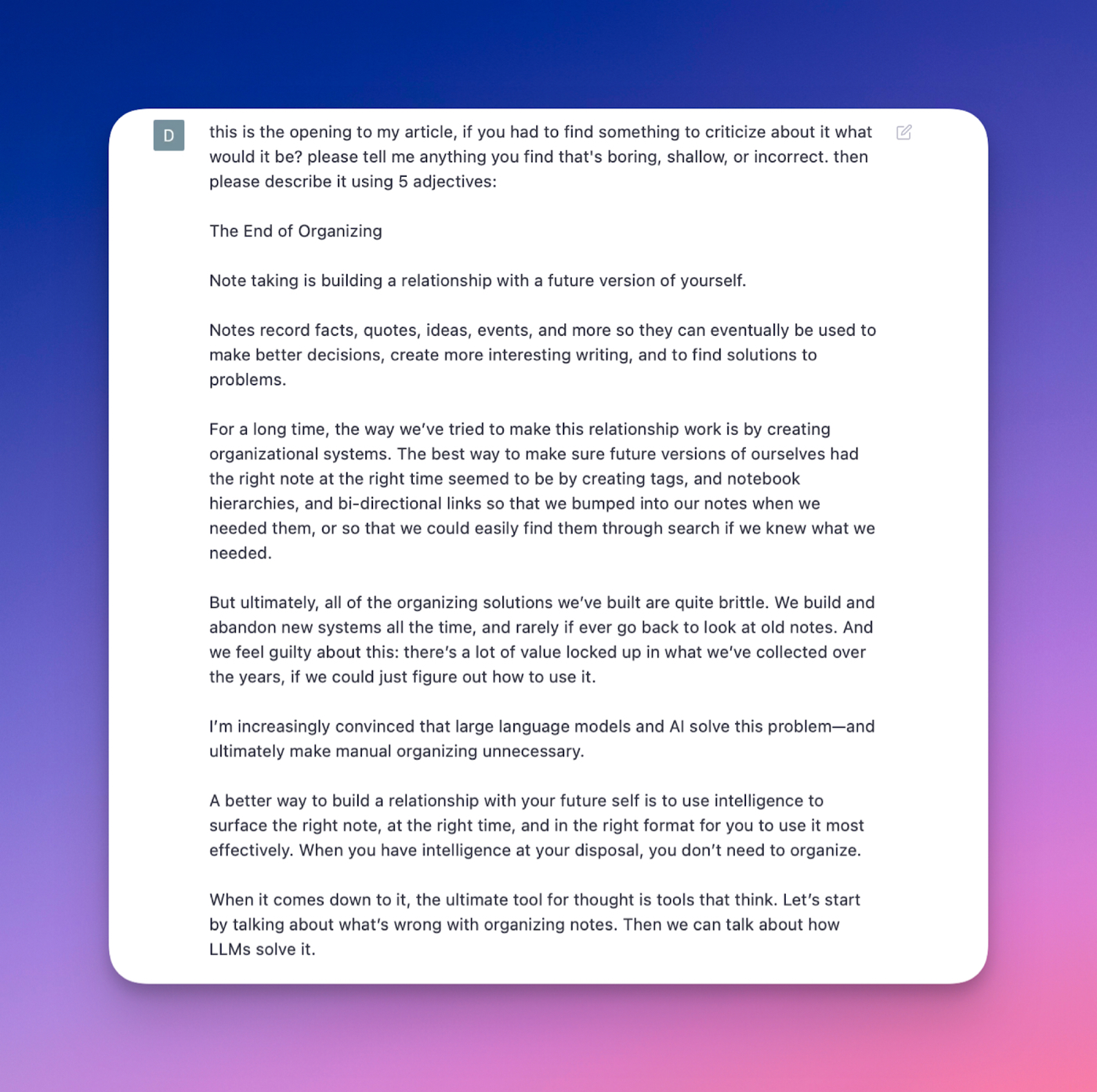

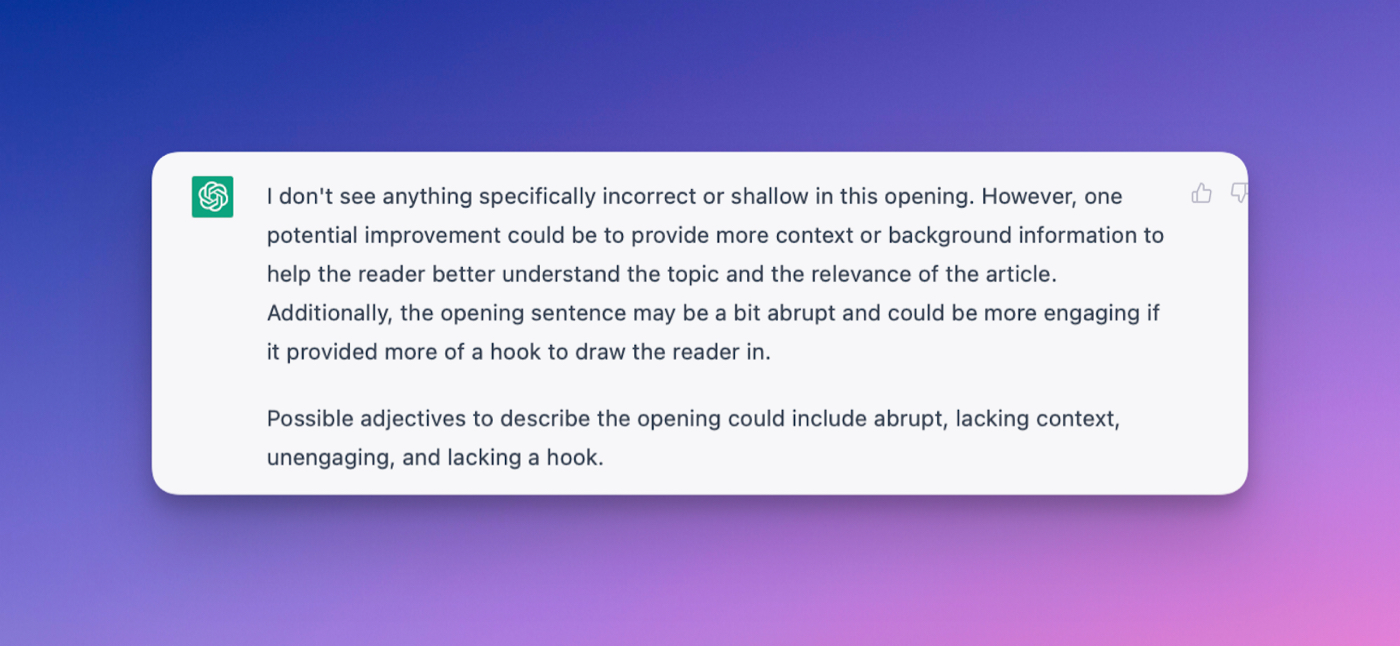

For example, when I was writing my “End of Organizing” piece, I wanted to know how well the introduction was working:

Here’s what ChatGPT had to say:It’s feedback is great: it told me that the opening sentence was a bit abrupt, and it was right.My original opening sentence to the article was: “Note-taking is building a relationship with a future version of yourself.” This is an important line, but it needs more context before you’re ready to read it. It’s not an opening line.

After I got this feedback from ChatGPT, I came up with a new opening:

“I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but all of the time we’ve spent organizing our notes was probably wasted.”

Then I moved the original opening a few sentences down, and it all worked a lot better.

Closing thoughts

In The Writing Life, Annie Dillard says, “The painter…does not fit the paints to the world. He does not fit the world to himself. He fits himself to the paint.”

Art, in other words, is the process of the artist learning to fit themselves to the tools they have to work with. Our definition of what writing is, and what the job of the writer is, comes from the tools we use to make writing.

AI changes the bundle of skills you can use to be a writer, but it doesn’t change the need for writing. Learning to master it as a creative tool is a good way to create new kinds of writing than were possible before.

And that’s a good thing for writers, and for the world.

Want to apply this essay to your work? Watch a 40-minute self-paced workshop on writing with AI, and practice with custom exercises.

You'll learn how to use AI as a creative tool to help you do the best writing of your life.

Curious? Learn more:

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Great article Dan! I loved the intro (super funny!) and the workflow. I will make good use of it :-)

To get access to Lex as a subscriber, should I still use the form that was shared back in October in "How to access Lex"?

@Alex Adamov yup! or if you want DM me on our Discord and I'll get you taken care of :)

Apparently, Lex iśnot accessible right now. It put me on a long waiting list

@oluwadiya you should have access if you're a paying subscriber! join our Discord and request it in the #lex channel and we'll get you set up :)