.png)

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

The first time I pasted a draft of an essay I’d written into the AI Every editor and it told me, “Spark is in the right place,” I practically whispered, Thank God.

After weeks of error messages and failed demos, that tiny seal of approval proved something I’d started to doubt: Maybe you really could teach a machine to spot what makes Every’s writing work.

The relief was technical—finally, a version that didn’t collapse the moment I touched it—but it was also personal. It felt almost like a pat on the head from a real-life editor. I knew exactly how the feedback was generated, based on the examples I’d chosen, the values I’d spelled out, and the rules I’d written down. Still, when the system returned its blessing, I felt proud.

Previously, I described the winding path to building Every’s AI editor from a technical perspective. This time, I want to talk about what it took to teach AI Every’s taste—collecting examples, writing down patterns, and translating our instincts into a playbook the system I set up as a Claude project could follow.

I was surprised by how clearly my own judgment came into focus once I tried to write it down for AI. When you can teach taste to a machine, you’re forced to make it legible for yourself. Some rules you already know; others only reveal themselves through explaining. The Claude project gave me the vessel, but I had to decide what belonged inside.

Before you can teach taste, you have to define it

When I first taught an AI editor, the only writer it had to worry about was me. The version I built for my column, Working Overtime, was tuned to its quirks: Start with a problem I was having, use personal stakes to frame insight, surface a bigger cultural pattern, land on a sticky phrase. If my piece is missing one of these components, my editor will call it out. These rules made sense for me, but they didn’t belong in Every’s rulebook.

In order to adapt the editor so that it worked for the team, I had to change my relationship with my own opinions. It was no longer enough to encode what I personally liked or thought was good. I had to draw a line between my own preferences and Every’s values, deciding which instincts deserved to become rules that applied to everyone. I had to collect evidence beyond my own hunches: the essays CEO Dan Shipper had flagged as canonical, the ones the data told us our audience couldn’t stop reading, the pieces we all pointed to as “this is what Every sounds like.” Then I dropped those examples into ChatGPT (I migrated to Claude after the release of Opus 4, but we’re reaching back in time) and asked the model to tell me what it saw.

The results read like an X-ray of Every’s signature moves. Strong introductions followed a rhythm: the spark of the idea on top, stakes established within 150 words, a quick zoom out, then a thesis pointing forward. Abstraction worked best when grounded in detail. Endings didn’t recap what had come before; they reframed.

Some of this we already knew. We’d been workshopping headline-subheading-introduction alignment in editorial meetings for months, reviewing each published piece and talking through how each component drew the reader into the piece (or didn’t). But seeing those judgments summarized in the chat window turned instinct into something visible, structured, and transferable.

Patterns alone don’t make a voice. To capture Every’s, I wrote in the three principles no model was going to surface on its own: optimistic realism, intellectual generosity, and conversational authority. Here, I let my own judgment creep back in. I had certain opinions about what makes Every Every, and I wanted those values to be baked into the editor’s DNA. Optimistic realism keeps us from lapsing into cynicism. Intellectual generosity makes sure we argue in a way that invites people in, not pushes them out. Conversational authority reminds us that confidence can coexist with humility. Without those anchors, the rules risked describing a style, not a voice. Style is the “how”: the choices of syntax, rhythm, and imagery that shape the prose. Voice is the “why”: the convictions that give those stylistic choices meaning.

How to boss a robot around

Patterns and values on paper were a start, but they didn’t mean much until I could teach the system how to use them. Models don’t understand a rule like “spark should be on top” unless you spell out what “spark” means, how to find it, and what to do when it’s buried. The next step was translating taste into instructions precise enough that an AI could enforce them.

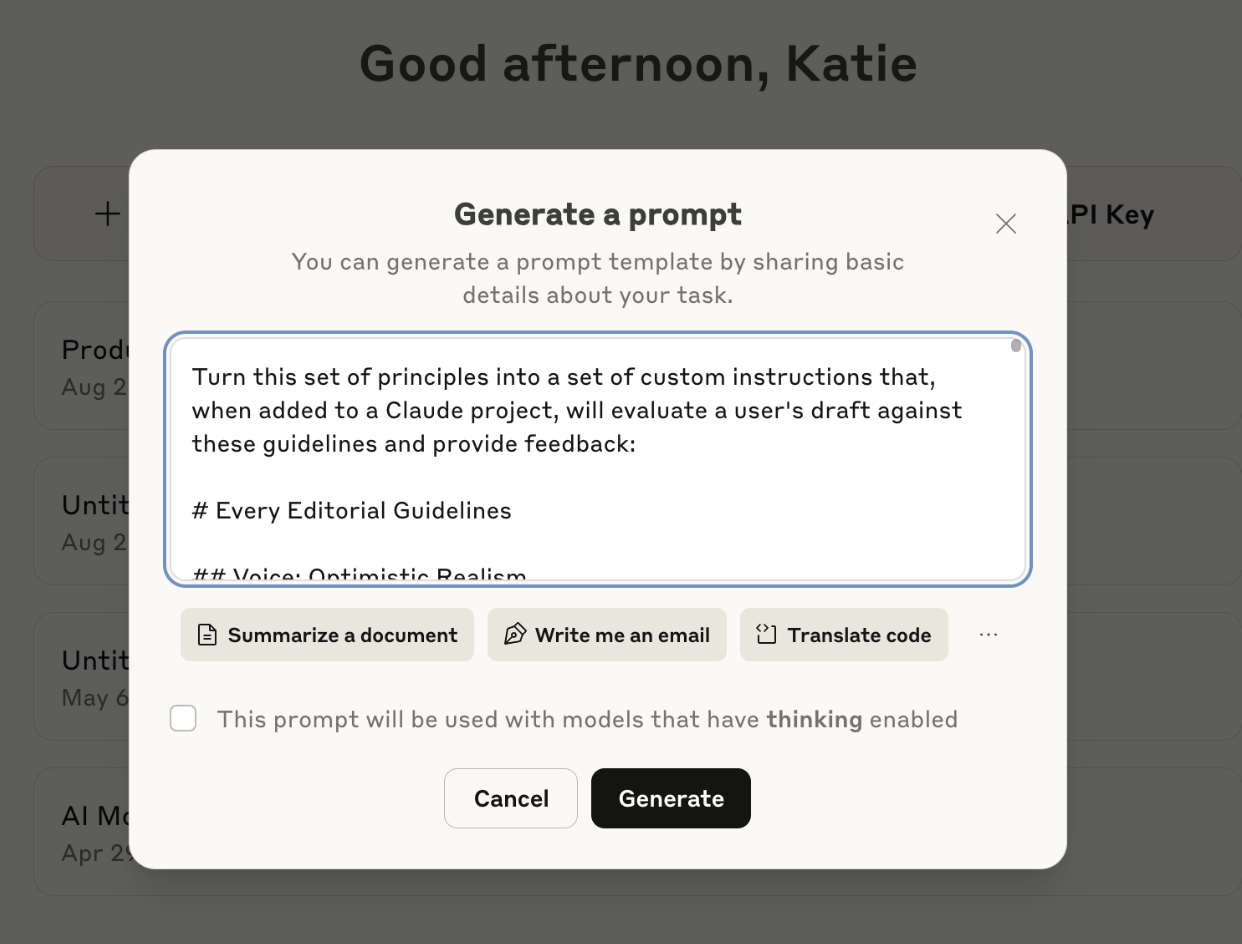

To help, I leaned on Anthropic’s prompt builder, a feature in the Anthropic Console that generates optimized prompt instructions for you based on information you give it about your goals. I pasted the list of principles and rules I’d developed with ChatGPT into the prompt builder, and it translated that content into a set of custom instructions that, when hooked up to the Claude project via project files, would act as the editor’s brain.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.png)

.53.16_AM.png)

Katie Parrott

Katie Parrott

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Hi Katie, I'm curious whether you've experimented with doing something similar via Lex? I did the Write of Passage writing course last year and have sought to codify some of the key principles I learnt there into prompts within Lex. It seems to work well for me when I'm writing, but I haven't tried is in a multi-player or third party editor kind of scenario.