Sumeet Singh has spent his career placing bets on the future—first as a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, and now as founder and managing partner of Worldbuild. After eight years of investing and conversations with hundreds of AI founders, he’s noticed a troubling pattern: Most are building specialist AI tools the same way they would have built SaaS products a decade ago. In our latest Thesis, he makes the case that this approach is a trap. Drawing on Richard Sutton‘s “bitter lesson”—the idea that scale and compute always beat specialization—Sumeet maps out the two paths he sees for founders who want to build something durable: Either build what models need to get better, or invent entirely new workflows that only AI makes possible. Read on for his breakdown of both paths, and the question every founder and investor should be asking right now.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

I’ve spent the last eight years as an investor—at Andreessen Horowitz and now at my own firm, Worldbuild—watching the same pattern repeat. Software was locked in an era of homogeneity, one dictated by a well-trodden path of fundraising instead of true innovation. It was the same unit economics, same growth curves, and same path to Series C and beyond. Founders optimized for fundraising milestones instead of for building sustainable businesses, leading to companies that raised too much capital at too high valuations.

That era has ended with the advent of generative AI and the end of easy monetary policy. As an investor, I’m excited; AI has finally opened up the potential for real innovation that’s been missing since the mobile revolution. But I see founders building specialist AI products for marketing or finance as if they were building the same subscription software tools of the last decade. Those who are playing by the old framework are about to make a big mistake.

To achieve an outcome attractive enough for venture capital investors in this era (i.e., multi-billion dollar exits), founders today need to absorb Turing Award winner and reinforcement learning pioneer Richard Sutton’s bitter lesson. Sutton’s prognostication was first proven in computer vision—an early AI field in which computers were trained to interpret information from visual images—in the early 2010s when less sophisticated but higher data volume dramatically overthrew the manual programming that had dominated the field for years. Specialization eventually loses out to simpler systems with more compute and more training data. But why is this a bitter lesson? Because it requires that we admit that our intuition that specialized human knowledge is better than scale is wrong—a hard pill to swallow.

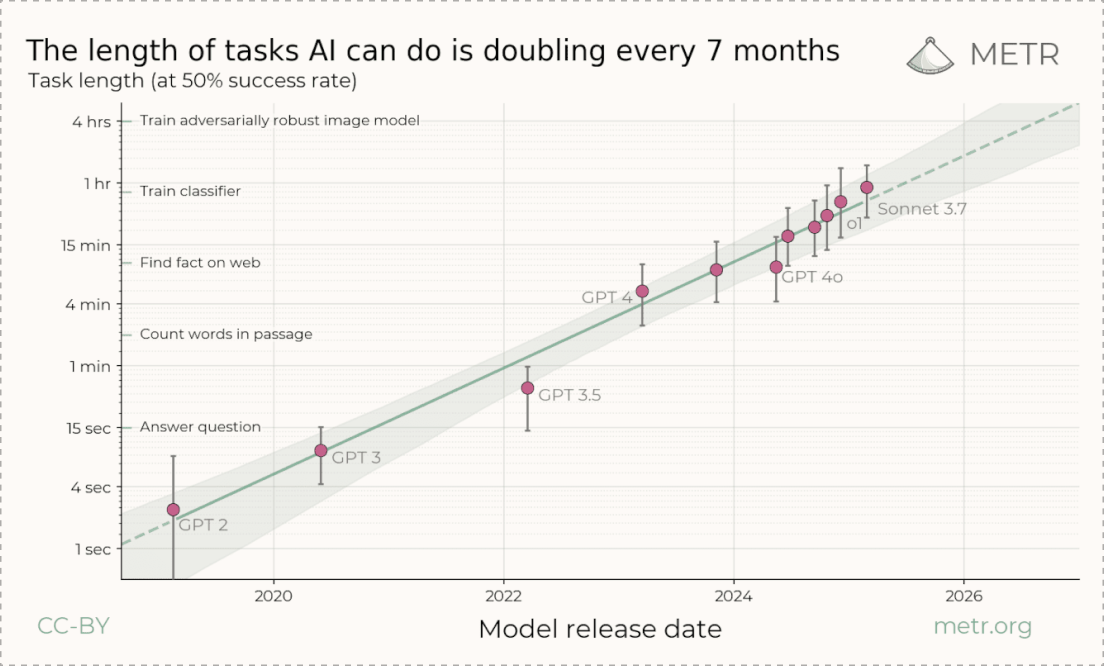

It’s already happening. It’s easy to say in hindsight that it was obvious base models would make early AI writing tools irrelevant, but this fate is coming for every specialist AI tool that bolts on AI models to some existing workflow—whether that’s in finance, legal, and even automatic code generation. Every one of these special tools believes it can create specific workflows with models to beat the base models, but the primary problem is the base models are becoming increasingly capable. The length of tasks that generalist models can achieve is doubling every seven months, as the graph below shows. Their trajectory threatens to swallow any wrapper that is built above them.

After talking to hundreds of early-stage founders building with AI, I see two paths emerging. One leads to the bitter lesson—and irrelevance in 18 months. The other leads to the defining businesses of this era. Those defining business fall into two categories: companies that build what models need to get better—compute, training data, and infrastructure—or companies that discover work that’s only possible because of AI.

Let’s dive into what each category looks like—and how to know which one you’re in.

The first path: The model economy

One way to build alongside the bitter lesson is to think about AI as both a technology to build with and one to build for. With the latter, I am referring to businesses that develop data or infrastructure that enables and enhances model capabilities, as opposed to creating applications that utilize AI as they exist today. I call this the “model economy.”

Many companies building at scale are already riding this shift by selling to labs directly. Those include Oracle, which is increasing its pipeline of contracts to supply compute to model builders to nearly half a trillion dollars. AI cloud companies CoreWeave and Crusoe have similarly been beneficiaries of this wave, pivoting from bitcoin mining to compute and data centers for AI labs, as has Scale AI, with its recent $14 billion investment from Meta to provide high-quality, annotated data for training large language models.

Four big opportunities in the model economy

There are four areas where large, sustainable model economy businesses will be built:

Compute as commodity

AI capabilities will continue scaling along an exponential curve, requiring ever more compute (chips) and energy. But in the short term, expect volatility: Hyperscalers yo-yo between a surplus of GPUs—the specialized processors that power AI—and scarcity within quarters. Microsoft, for example, went from GPU glut to shortage earlier this year. The most durable startups will prepare for both realities: the certainty that AI needs more compute, and the chaos of supply crunches and gluts. We’ve been investing in the “exchange model”—companies that match supply and demand of compute or energy, increase asset utilization (e.g., ensuring chips run at full capacity instead of half), and build mechanisms to trade these resources)—such as AI compute marketplace the San Francisco Compute Company and Fractal Power. These companies withstand volatility and even benefit from it. Meta’s venture into wholesale power trading, a move that would help the company secure flexible power for rapidly growing AI data centers, signals where this is headed. First we’ll trade the electricity that powers AI, then we’ll trade the computing power itself.

AI that lives on your devices

Some AI can’t happen in the cloud due to latency (or real-time response needs), privacy, connectivity, or cost constraints. Take, for example, a hedge fund analyst who wants a model to reason on a trading strategy for days without exposing it to anyone. In this category, specialized hardware and networks run and manage powerful AI models locally, not in someone else’s cloud. Winners will couple hardware and software tightly for AI experiences that happen on a device. Meta, with its continued investment in wearables, is one example, as is upstart Truffle, which is building a computer and operating system for AI models. This category could also include companies that create local AI networks that pool computing capacity from a variety of sources, including computers, graphics cards, gaming consoles, and even robotic fleets.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.png)

.png)

.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Brilliant Essay, Sumeet! Where can i go to find out more about how you're deploying this thesis?

This was a terrific piece Sumeet. I kept coming back to this several times in the week after i read it. The biggest takeaway for me from this piece is Richard Sutton's Bitter lesson. I love the piece you have hyperlinked and also this terrific video by Richard Sutton (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RrXibq7-W6o). Even for a non coder like me, it makes so much sense and ultimately helped me give up on every other AI tool out there and do double down on learning Claude Code.