Sponsor Every!

Every is now accepting select sponsors. We’re looking for companies who want to bring new tools, systems, and technology to our audience of 45,000+ founders, investors, and operators in tech.

Interested?

With military precision, the painter Brian Rutenberg wakes up every single workday at exactly 7:10am. Then, the ritual begins: a series of daily tasks, guided by muscle memory and the power of his immutable routine. He arises and makes his bed, then twenty minutes at the gym, followed by oatmeal and coffee at the same diner, every day.

Then he heads into his New York studio, where churns out some of the most well-regarded abstract paintings in modern art. Every day. On time. For decades.

You'd think if his output is as consistent as clockwork, his creative process would reflect that too, right? Wrong, my friend. Wait till you see the pictures of this studio of his—Oh, by The Divine Sweet International Lamp-Lighting JEEBUS.

Calling Brian Rutenberg’s studio ‘a mess’ would be generous, even fussily genteel. ‘Unholy dump’ would be closer to the mark. If Shakespeare or another of our great poets had seen it, he might have called it ‘a festering hellhole’.

Here in this festering hellhole, Rutenberg steps over greasy mounds of discarded paint and heaps of paper, garbage, and assorted shit to reach his desk, where he deals with daily to-dos by taping his notes onto a rickety old revolving lampshade. When he gets down to the actual work of painting, he snaps his paintbrushes in half—they’re ‘an extension of my fist’, he says—before he uses them to smear wads of oily paint across expanses of canvas.

And he doesn’t make ‘art’, by the way—he makes things. Because art is a lie, he says.

But art will also save the world. He says that too.

I stumbled across the fascinating bundle of contradictions that is Brian Rutenberg somewhere in the early days of the first lockdown, when a friend sent me images of his incredible paintings—the luminous and vibrant colors were soul-medicine in the drab bleakness of early Covid. The first thing I found out about him is that he is reckoned to be one of the finest American painters of his generation.

As my interest in the guy grew, I found his riveting (and hilarious) YouTube channel. Then, I got hold of his best-selling book Clear Seeing Place, too. His videos and book are a distillation of his thoughts on how to be a painter—a manifesto in poetic prose.

His work and his words started out as a welcome diversion from the pandemic and all the other anxieties available to the modern consumer—but they soon became inspirational guiding lights for me in my own privileged personal process of pandemic-induced self-reëvaluation.

The closer I looked, and the more I learned about his approach to work, the more I was able to understand both the routine he keeps, and the messes he makes. There are intense moments of accumulation and clutter and filth, yes, but surrounded by space—space for work, for reflection, and for painting.

You see, it turns out that Brian might well have thought more about the stuff we’re interested in at Superorganizers than anyone we’ve ever profiled. From how he structures a day in his life, to how he works with purpose to satisfy the rigorous demands of his relentless year-in year-out schedule of shows, to why a sense of purpose is infinitely more powerful than any amount of inspiration.

He knows what he’s doing, and why he does it—and he knows damn well how he’s going to do it, too. And, crucially, he knows how to talk about it, in fluent Rutenberg:

‘All the talent in the world is meaningless without an atomic work ethic.’

‘The only way to be a painter is to make paintings. That means not doing other stuff.’

‘Life’s only commodity is time. How will you spend yours?’

Maybe you already know who Brian Rutenberg is; hell, you might even have a Rutenberg on the wall of the bathroom where you now sit, enthroned, thumb-scrolling through these words. Or maybe you can’t tell cadmium orange from a navel orange—or couldn’t care less whether phthalocyanine is a shade of blue or the most efficient poison to eternally silence your neighbor’s yappy little dog.

Either way, join us as Brian Rutenberg invites us into his New York studio and tells us why painting is, as he says, ‘this thing that keeps calling him back—like an animal demanding to be fed.’

Be careful where you step, though, and make sure not to touch anything—honest to God, there’s crap everywhere.

Brian Rutenberg introduces himself.

Being a painter was never a choice for me.

Since I was about 10, I’ve been able to draw whatever was in front of me. I don’t mean that I could make academically polished drawings at that age, but I had an innate ability to render the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. Even then, I saw the world as shapes and colors, which made it easier to draw and paint shapes and colors. It’s also a valuable skill to have at boring dinner parties.

But in addition to representing what I saw, I could also summon imagery from my imagination, and draw it too. I somehow had the ability to tap into what’s visible and what’s invisible—and I figured out that I was good at it. While my friends were outside playing basketball, I was alone in my room doing what every young man does: making classical drawings.

Today, I describe myself as ‘a landscape painter born and raised along the coast of South Carolina, who lives in New York City.’

A schedule is the only thing a painter can rely on.

My entire philosophy of how I organize myself as a working painter can be summed up by something George Carlin said: “Just keep movin’ straight ahead. Every now and then you find yourself in a different place.”

You hear a lot in art school about how painters must continue to ‘grow’ and ‘evolve’—but I think those are such bullshit words. There is great poetry and power in repetition, in doing the same thing over, and over, and over, and over again. No one talks about that.

Day after day, decade after decade, I show up at my studio and hack away at that gigantic slow-moving iceberg that sits in the middle of the floor. If a piece breaks off, I get a painting. I think of it very much as a 9-to-5 job, not a ‘creative vocation’, and not really even as a ‘career’. It’s just sheer persistence.

Creativity is born of limitations, not freedom.

My limitations start with my routine. In the morning, I wake up at exactly the same time every day—7:10. I sit up on the bed and I don't do anything—I just sit there and wait. Every time, without any conscious intention, I stand up, go brush my teeth, and start my routine.

A painter must trust muscle memory: do first, think second.

After I get dressed, I make the bed. It’s important to start the day with some task that has a beginning, a middle, and an end. I go to the gym for twenty minutes and then I head to the diner to meet my actor buddies for oatmeal and coffee. We talk about life as artists in NYC, being parents, and whether to eat a slice of pizza flat or folded (I fold).

I get to my studio at 9:45 or 10. I usually do paperwork at my desk—I have admin work and correspondence to deal with, like any creative person. From my desk, I can see my painting wall:

I’ll look up intermittently at whatever I was working on the previous day, and that’s when it becomes clear to me what direction my work will take for the rest of the day. Just like getting out of bed, I trust my muscles to do what has to be done.

I take lunch at about the same time every day, 12:45, and it’s always the same thing for long stretches of time (lately it’s shrimp pad thai and Thai iced tea, in case you’re wondering). After that, if all is going smoothly, I’ll paint until 5:30 or 6, and then go home. I’m a family man. Weekends and evenings are for spending time with my wife and kids.

When I get blocked in my work, I just quit.

I used to think that the best thing to do when experiencing a painting block was to put my head down and try to push straight through.

Now I try to think of the word ‘block’ from a different angle. A colon gets blocked; an artist has dry spells. A dry spell is a good sign: it means you’re working. The only certainty is that you will fill up again—but you can’t force the Muses.

My advice: give up. I once read an anonymous quote that said, ‘All grumbling is tantamount to “Oh, why is a lily not an oak?”’

My mother loved the stand-up comedian Phyllis Diller who said when the audience doesn't think you're funny, quit—simply do something else. There is nothing weaker than a painting that tries too hard. Do what comes easily. When it stops being fun, you’re doomed. If a painting sucks, I quit.

I put everything down and I go take a walk, or go eat at a diner, or meet up with friends, or go to a movie or the Met—whatever. And I’ll know when it's time to go back to work. It will make itself obvious to me, and I trust that feeling.

How I keep track of everything I have to do.

For ages, I kept myself organized with Post-It notes, all crammed into my wallet or stuck onto the mirror in the bathroom. I could see everything in front of me, in a very tactile, lizard-brained way. I crumpled up each note as each task was completed.

Now I try to use my phone, but I need help with the calendar features. As my friend, the actor Richard Kind, says, “The reason I had kids was for tech support”—my kids helped me set up my notes and calendar so that I can see everything I've got to get done.

I have to set reminders to look at the reminders—but I get stuff done efficiently and punctually. As my Dad used to say, “If you're early, you’re on time; if you're on time, you're late; if you're late, it’s unforgivable.”

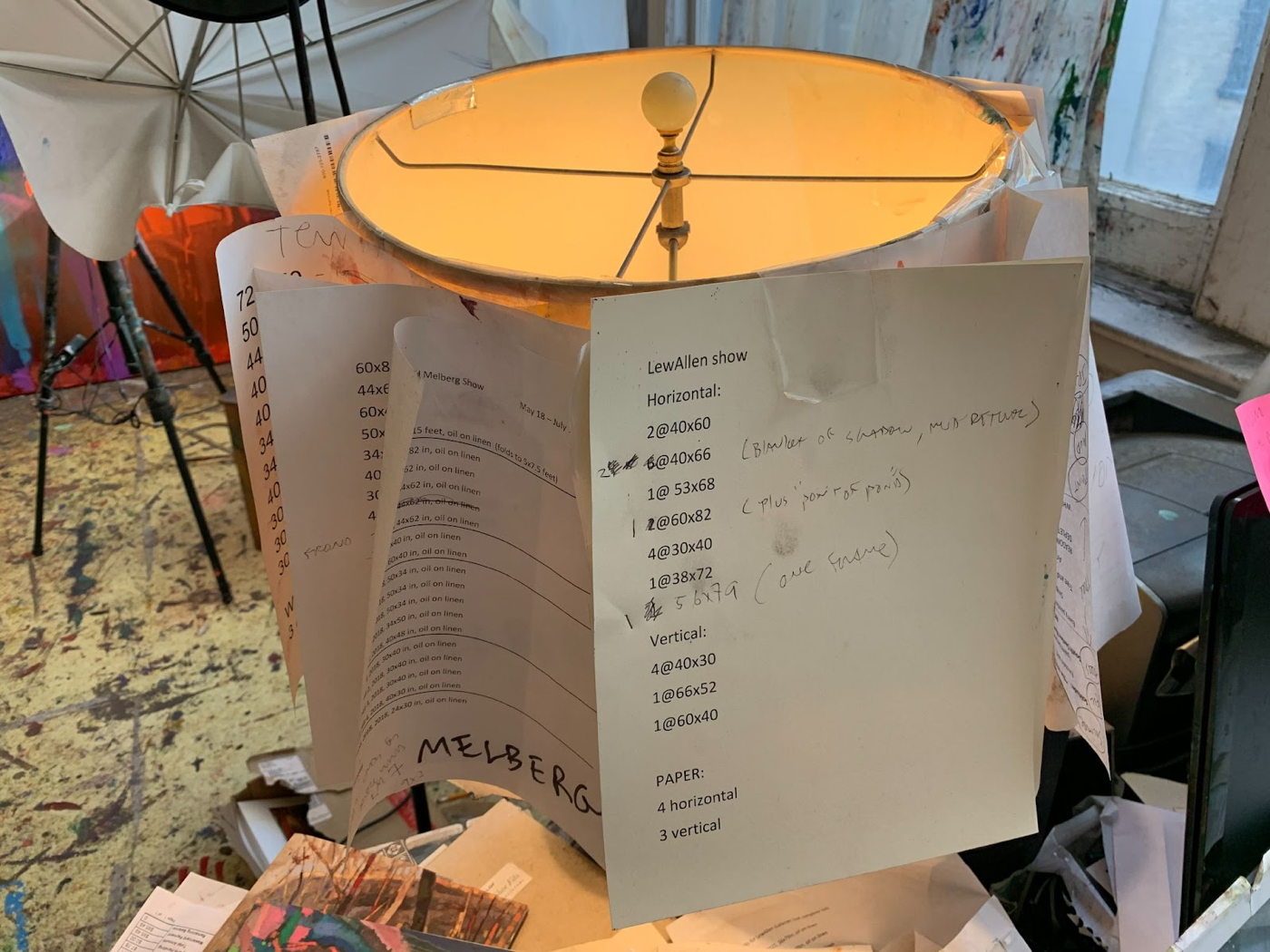

Here in my studio, my ‘system’ is a little bit more organic and handmade. In this photo, you can see a lamp with a cylindrical shade that I keep on my desk. I tack notes of the things I have to get done onto that lampshade. I can spin it around, which reminds me of the days when I worked in a restaurant back in Myrtle Beach—they had these spinning aluminum carousels where diners’ orders were posted.

The lampshade keeps the important stuff laid out in front of me. On my desk, you can see that I have a stack of papers. That’s where I jot various things down. Somehow, I know where everything is in that stack:

One last thing: I often write stuff directly on my hands, which I believe is a very old and efficient practice dating back to Aztec culture. Chances are I won’t lose my hand!

There’s a good reason my studio is a mess.

At first glance, my studio looks like an Italian air show—a disaster. But upon further inspection, you can see that there is a method to the mess.

For me, creativity isn’t born when everything is tidy and separate. It comes from cross-pollination, unexpected combinations, and head-on collisions between things that don’t necessarily go together.

When I buy a new paint brush, the first thing I do is break it into halves. A brush is not a sacred implement that makes precious marks, it is an extension of my fist. Anything precious is self-conscious, and that kills creativity. I spill everything out and fix it later. I disrespect my tools but I respect what they do. I never want to lose the sense of play.

Amidst the chaos, I run my studio like a well-oiled machine. My dealers will back me up on this: they all love working with me because I get everything done on time, even ahead of schedule.

My paintings are a direct extension of my active, sloppy workspace.

Oil paint is crushed rock, mixed with liquified fat, and smeared on cloth with a stick. Yet it can suggest light where there is no light, and space where there can be no space.

At some point you're going to have to make peace with the fact that paint is a physical material, and either a.) it’s going to work in the way that you put it down on canvas, or b.) it ain't going to work.

In that case, I scrape it off, and dump it into huge clumps on the floor.

I leave those piles there: it's both a symbolic and a practical reminder that this work is fraught with mistakes and errors. It's also a reminder that painting, and all art, is a lie.

There’s a reason the first letters of the word ‘artificial’ are ‘art’. Human beings crave deception—we need to see each other’s narratives. We make art so that we have an excuse to stare at each other.

Peering into someone else’s heart grants us a stronger purchase on our own. Art is empathy, and it will save the world.

We lie to the viewer to get them to step out of the real world, which is governed by all the natural laws we know, and step into an artificial one. That’s why all art is political. Whether you see Hamilton on Broadway or a watercolor of kittens in a basket, you are submitting to the entire political belief system of the artist. The creative act has one purpose—to obliterate the way we see the world and force a new way—the very definition of politics.

The process of bending the laws of nature to fit the laws of art is nothing new. It’s what Cézanne did, it’s what Goya did, it’s what Rembrandt did, and it’s what I will continue to do until I die in office.

There is no upside to a fear of failure.

If your intention is to ‘make art’, then maybe you’ll get a couple of good paintings. You may even get a show or two.

But I think of it this way: I don’t make art. I make things. Framing it like that keeps what I’m doing from becoming precious. And that’s a good thing, because to be precious is to be timid—and that’s bad. Creativity requires attention to detail and persistence in the face of failure: that’s why it’s called a ‘discipline’. Every painting fails before it succeeds.

If you’re afraid to go just that bit little farther and fuck the whole thing up, then you’re in trouble. You’re painting with one hand tied behind your back. My old teacher, the British painter Michael Tyzack, used to say, “Without risk, there can be no serious painting.”

Michael was my beloved second father back when I was at the College of Charleston from 1983 to 1987. He died in 2006, but there's not a day that goes by that I don't think of him. I have his palette and the template he used for inscribing his name on the back of all of his books, so he’s always here with me.

How I overcame a fear of making mistakes.

I spent a period of time where my goal was to plow through work in the cheapest and most disposable way possible. My choice was cardboard—sheets of corrugated cardboard from the streets of Manhattan.

I’d haul it up to my studio in big bundles every day, and put it all over the walls, the floor—even on the ceiling—and make imagery on it. At the end of the day, I’d pack it back up into bundles, and haul it back down to the street.

The best way to find your voice is to make a lot of work and then destroy it.

There was something really satisfying about seeing garbage come into my studio, and then seeing it go back out—as garbage. That’s how I learned to trust my gut. There are no talent scouts. You are totally on your own. No one cares if you fuck up, believe me.

I just put ideas into visual form as quickly as possible. My teachers loved it because they had a new body of work to talk about every week—as opposed to the kid next to me who spent the semester pondering whether or not to glue a penny to a canvas…

Purpose is way more powerful than inspiration.

I always think of ‘inspiration’ as an amateur word. Inspiration is being propelled to do something, or to think something, or to go somewhere, by some sort of external stimulus. And that to me is undependable.

But purpose—purpose is a white-hot fire inside of you, a self-delusion that keeps you coming back into the room to work decade after decade, knowing that you'll never get it right, but that the next day might get you a little bit closer…

The worst thing you can do is make a plan. The heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” The only thing I can rely on is a schedule. I simply show up and work within the limitations I’ve preset for myself.

Art comes from self-delusion. If you don’t believe, then how can you convince others? Don’t try to be great, just be good. Any clown can hit one out of the park once in a while, but it’s much harder to be good consistently.

How I got a career.

I used to think that just because an artist has work in a gallery or museum, they must be good. It’s not true—they’re lucky. If that same artist still has work in a gallery in twenty-five years, then they're good.

If your work is to have integrity, it must come from the inside. Everything you need to be creative you've probably possessed since you were ten years old. Just show up, regardless of the results, and scream down the well with every inch of your lungs. That’s how you get a career.

When it comes to my own career, I’m very fortunate to work with the best dealers in the business, who organize, document, transport, promote, and guide me. It is important to surround yourself with people who are better at stuff than you are. Never be the smartest person in the room. I never am.

In general, I do two solo shows a year, which are usually booked five years in advance.

For each show, I’ll do ten to twelve paintings of different sizes, depending on the gallery space. I show with seven different galleries around the country, so each gallery gets a show every three years or so.

I know exactly where I’m going to be in five years, which keeps my schedule full and predictable. And in addition to solo shows, there are group shows and art fairs. All of that keeps my studio hot and full of work, with things cooking all the time.

I started making YouTube videos as a reaction to the routine of work.

Around 2011, I started to feel that my steady daily routine of feverishly working to put together all of those shows had left me running on autopilot. I was being very productive, but something was missing.

There's a great haiku that says, ‘My eyes, having seen everything, returned to the white chrysanthemum.’ I felt like I was at the point where I really wanted to return to the center—so I started to make videos as a way to rekindle the feelings that made me an artist in the first place.

I felt that so much of the art-related content out there was either too technical or too pretentious—and I hate all the ‘artspeak’. My approach was to say, “I'm going to be your friend. Come into my studio, and I'll show you what I'm doing and how I do it.” I wanted to communicate in ways that were down-to-earth, occasionally funny, and practical—things that people could actually apply to their work lives.

In the beginning, I sat in a chair and talked straight into the camera, but it looked like a hostage video. With practice, I loosened up and now I can speak with more ease as if you and I were talking to each other over a cold beer.

I wanted to show the ins and outs, and the unglamorous underbelly of this life. I have made it, I've done well, I continue to do well, and it's OK to say that. But it takes a lot of discipline, a lot of hard work, and luck, and I wanted to show that part of it too—in order to tell people that this is possible.

The process of making videos helps me in every aspect of what I do.

I’ve been making my videos for eleven years now, and there are almost eighty of them at this point. Making them has helped me to become more articulate. Speaking about your work and writing about it in clear language helps to clarify your intentions and communicate them to others.

An artist must be two people inhabiting one body—a maker and a talker. Make something and tell the whole world about it. It’s hip to claim that your work ‘speaks for itself’, but it doesn’t. You have to help it. Write about your work, every day.

When I’m writing a script for a video, I choose a theme that will tie it all together. I try to intertwine the technical aspects of painting with philosophical musings, or reflections on my experiences—and maybe I’ll throw in a little love letter to New York City or to South Carolina for good measure.

I memorize the first part of the script, and then I sit down and start speaking into the camera. It takes me about a week of filming and editing to make each video, and I do it all myself.

The videos have other benefits: the scripts that I write for the videos eventually become my books. I’ve learned how to look and speak into a camera, which in turn helps me when I travel around giving lectures. I’m also much better at speaking clearly about what I do—which hopefully will help other people speak clearly about what they’re trying to do!

Ultimately I’m the beneficiary of all of this, because I get to feel like I’m of use to others. Isn’t that what we all want?

I’m able to help others and build community through my videos.

At first, making the videos was a reaction to how cutthroat and competitive the New York art world can be. I longed for a sense of camaraderie and community—but on my own terms.

It's become critically important to me to try to put something into the world that might help other artists. And not just artists: my goal is to help people think more creatively, or free themselves from some rigid set of expectations that might be placed upon them. I want to give a sense of permission to people who always wanted to paint, but decided to do something else for practical reasons, or just out of fear.

Life’s only commodity is time. Why waste it comparing your inside to other people's outsides?

Now I get mail from all over the world—it might be from an artist in Mumbai, or Scotland, or in Missouri, and it all says basically the same thing: thank you for being honest and for taking the time to share what you’ve learned.

I know it seems like a bit of a cliché, but I feel like I’m paying forward what I learned from all the generous teachers it was my amazing fortune to have. I am honoring them by trying to be generous, too. After all, art is a form of gratitude.

I’m simply doing what I was taught.

A book I love

My favorite book is The Three-Cornered World, by Natsume Sōseki, published in 1906. It’s a novel about an artist who goes on a retreat up a mountain to a little inn, where he falls in love with the inn-keeper’s daughter. The story is propelled by a series of sensory experiences he is immersed in—it's essentially a word-painting about being an artist.

I first read it in 1986 when I was at The College of Charleston. At the time, I realized that there was so much about it that I didn't understand.

I think there’s great value in misunderstanding when you read. I like the idea of thinking that the author meant one thing—and being totally wrong about it. Ultimately, what you get out of a book doesn’t come from what you comprehend, but from what you don’t comprehend, at least not yet.

Every five years, I go back and reread The Three-Cornered World. When I do that, I always have a new interpretation—‘Oh, wait a minute, that’s what he meant!’ I’m never the same person I was the last time I read it. Since then, I’ve had a child or lost a parent, or had some deep experience that fundamentally changed me. As the painter Willem de Kooning said, “You have to change to stay the same.”

With every re-reading, I take possession of something I’d been missing the previous time. The greatest gift is when I recognize what I’ve never seen before.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!