How Should We Take Notes?

Digging into the philosophical roots of the battle between Tiago Forte and Conor White-Sullivan

June 26, 2020 · Updated January 21, 2026

“The trail of the human serpent is thus over everything.” - William James

How should we organize our notes?

It’s the bugbear of almost every productivity nerd, and answers abound: notebooks, tags, stacks, kanbans, links, bi-directional links.

In fact, there are so many answers to this question that people in our little corner of the internet actually fight about how to organize notes.

(Tiago is, of course, the creator of the organizational system PARA and fellow Everything bundle member. Conor is the creator of Roam.)

The lines of battle have been drawn this way:

Tiago thinks notes should be organized by actionability, and that each note should go in one and only one place in the following categories: Projects, Areas, Resources, Archives.

Conor thinks that notes should go everywhere, and that there’s no single top-down structure that can encapsulate all note-taking.

They’re both extremely intelligent and thoughtful about this topic — so why do they disagree so thoroughly? And how should we decide between them?

I think if we take the time to actually examine the disagreement we’ll be surprised. I don’t think they actually disagree about as much as it may seem. Second, I think gaining a better understanding of the philosophical source of their dispute will help to make us better note takers, and importantly, better thinkers.

Ready to dive in? Let’s go.

1

Let’s start at the beginning. Why are we fighting in the first place? Why is organizing notes so hard?

That’s a good question to ask.

One obvious answer is that organizing information is just hard. But it turns out that it’s only really hard for certain types of information.

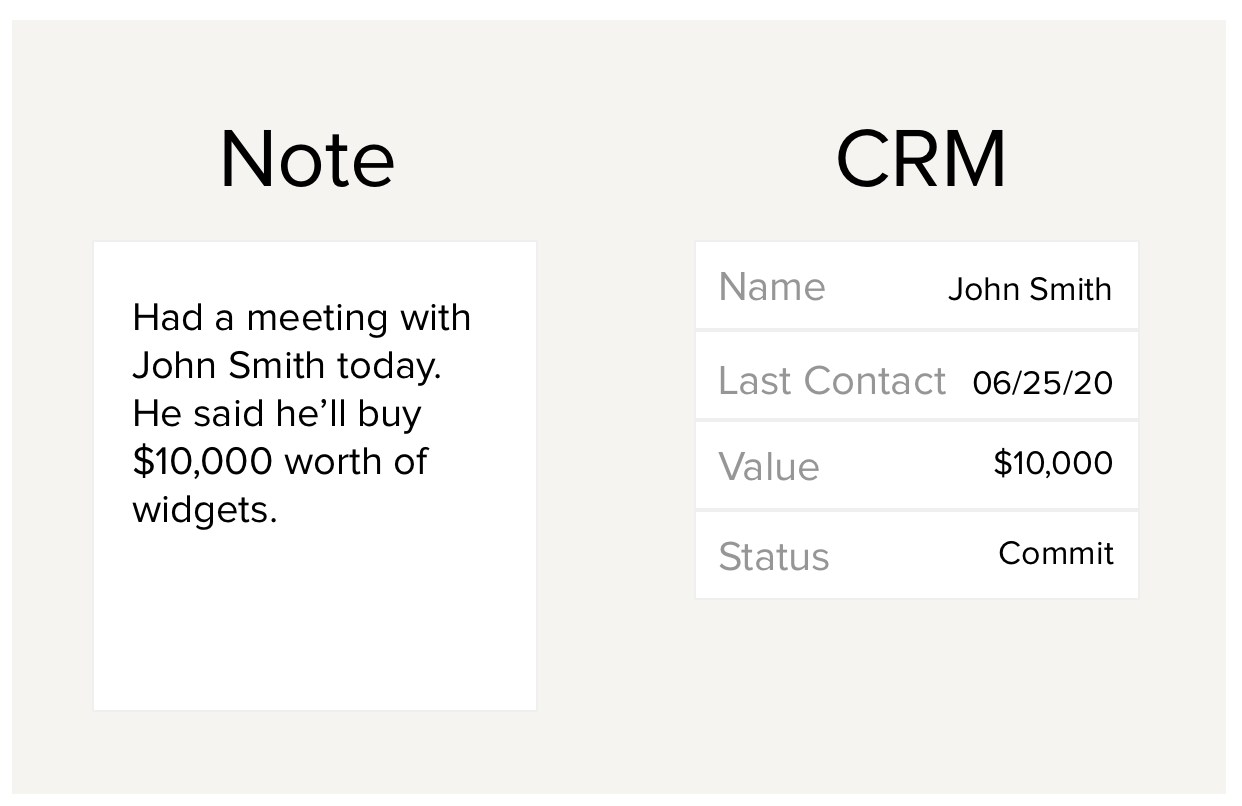

You’ll notice that there’s no great debate about the best way to organize the information inside of a CRM. It’s fairly obvious how to do that: a CRM should be a long list of customers.

If you want to get slightly more complicated with it you’d include a hierarchy. Each customer contains a list of attributes like name and address and phone number. Each customer is then contained inside of a company. Companies are contained inside of a geography.

You can see here, we just built a very basic organizational system for a CRM in a few sentences. It’s not so hard. There’s room for disagreement over details. But no one is disagreeing over the fundamentals in the same way that note-taking nerds are.

So why are notes different?

2

One way to think about knowledge management is as philosophy in action:

As we think about the best folder structures and tag hierarchies, we’re really doing philosophy. And it turns out that there’s a two-thousand-year-old debate in philosophy that’s pretty similar to the debate between Tiago and Conor.

Instead of being about how notes are organized, it’s about the way the world is organized.

The questions that this battle attempts to ask are things like:

What is the world?

What is it made up of?

How do its constituent parts relate to each other?

And how do we know?

On one side of the debate, roughly are people who believe that there is a world out there, that it is universal, objective, and accessible by the human intellect.

We’ll call these people essentialists. (Philosophers like Plato, Kant, and Descartes all fit under this label — though their philosophical stances vary widely)

Essentialists think about truth in a very specific way. They think that a statement is true when it reflects something essential about the way reality is organized. They think truth is defined as a relationship between a statement and a state of the world.

One the other side of the debate are people who choose not to answer that question directly. They believe, roughly, that there is no objective place from which to decide what is true. They believe that there are many different ways to represent and organize reality.

We’ll call these people pragmatists. (Philosophers like James, Wittgenstein, and Rorty — though their philosophical stances vary widely.)

Essentialists have a representational theory of truth. They believe that a statement is true when it represents the state of reality accurately.

Pragmatists have an instrumental theory of truth. They believe that a statement is true when it works — that the only way we can know if something is true is if, by acting according to it, the world reacts in the way we expect it to.

To a pragmatist, statements aren’t more or less true in the sense that they more or less accurately represent reality — statements are just more or less useful. The useful ones we call “true” and the not useful ones we call “false.”

Essentialists think pragmatists have a childish version of truth. They think that pragmatists are arguing that everyone can have their own personal version of the truth, which is counter to the very idea of truth.

Pragmatists think essentialists spend too much time reading books and not enough time paying attention to how life actually works.

More importantly, because of the way they think of the world, essentialists and pragmatists engage in significantly different ways of organizing it.

Essentialists have a hierarchical view of the world. Each object in the world should fit into one and only one category, and each category should nest within a well-defined hierarchy. You can see essentialist principles in many places — like the system we have for categorizing animals, Linnaean taxonomy. Each animal fits into one and only one kingdom, species, genus, etc.

For essentialists, it’s the philosopher’s job to define these categories and figure out where each thing in the world fits. Each thing has one and only one true place.

The pragmatic organizing project is very different. Pragmatists tend to have a networked, relational view of the world. They believe things are defined by their relations to other things, and that there are many different, valid ways to interpret what objects are in the world and how they relate to each other.

To a pragmatist, what we call an object and how we categorize those objects are just a matter of perspective. Objects in the world can be placed in many different categories at once — we choose which categories and relationships are most relevant based on context.

To make this more concrete think about a chessboard. In our everyday experience, it feels like a solid and self-contained object. But we also know scientifically that it is made up of billions and billions of invisible atoms.

So, is a chessboard one thing or is it billions and billions of things?

Essentialists might say that it is one thing — a chessboard. That it participates in some fundamental way with the is-ness of a chessboard. Other kinds of essentialists may say that though we call it a chessboard, that is actually just a nice shorthand for what it really is which is a collection of atoms arranged in a certain way that looks like a chessboard.

By contrast, pragmatists just shrug. They say it is both a chessboard and it is a collection of atoms. A chessboard is one way to talk about it in a particular context. A collection of atoms is another way to talk about it in other contexts. Both are useful shorthands, but they don’t indicate anything essential or deep about the chessboard itself. They’re just more or less useful descriptions.

Essentialists are trying to find the fundamental piece of reality that makes things what they really are.

Pragmatists just think there are lots of different ways to describe reality and some ways are more or less useful in certain contexts.

3

Okay so let’s go back to the original question: why do we debate how to organize our notes when we don’t debate how to organize a CRM?

To start to answer this question we need to notice something really important about software: all software does the same thing.

Software lets us record information, store it, transform it, and then retrieve it at an appropriate point in the future.

That’s what every piece of software does. Some pieces of software we call spreadsheets, some software we call CRMs, some we call Facebook, some we call Mario Kart. But they’re all fundamentally the same thing.

They’re just ways to record, store, transform, and manipulate information.

But somehow a CRM feels different than a notes app. That’s because CRMs attempt to represent the world. CRMs have all of these interesting objects inside of them. They have customers, they have companies, they have geographies. All of these things exist in a hierarchy — customers are inside of companies, companies are inside of geographies — and the hierarchies very much correspond to something true about the way the world works.

By contrast, notes apps don’t do that. You’ll find no “customer” or “book” organizational structure inside of a notes app.

Instead, we have “notebooks” or “notes” or “pages.”

This may look similar to the information structure inside of a CRM, and in a way that’s true. A CRM has customers, and a notes app has notes.

But it’s fundamentally different in an important way. In the case of a CRM the “customer” is a direct representation of something in the real world that you’re trying to record information about. When you use a “customer” record in a CRM it’s because you’re recording something about a real-life customer.

When you use a “note” in Evernote you are not writing about notes. You are writing about an undefined and infinite number of different things. “Note” is just a catch-all term for a blank page. A “note” is a box you can stick anything into.

If you’re paying attention, you’ll notice that this relates in a deep way to the essentialist vs. pragmatist debate.

A CRM is an essentialist piece of software. A CRM knows the essential objects in the world that it needs to care about: customer, company, and geography. It creates information structures to represent those objects, and then relates them together in a unified and standardized way. A CRM is creating a little model of one corner of reality.

A notes app is not essentialist in the same way. Yes, it has a notebook and note structure but those are more or less unopinionated containers. When it comes down to the actual information contained inside of those notes, it throws its hands up and says, “I don’t know the structure!” and just gives you a big blank box to throw all of the information into.

Why is that?

You might think the answer is, Ah, the people who make notes apps are pragmatists and the people who make CRMs are essentialists. But actually, no. I think this sliding scale of organization from rigid and hierarchical to flexible and networked is actually an example of pragmatism in action.

Pragmatism doesn’t preclude rigid, hierarchical organizational systems — it just tells us that there are infinitely many such systems, and some of them are useful in specific contexts.

When the context becomes more clear, it is actually useful for the organizational system to become more rigid and hierarchical — it’s not a bad thing!

I think by default, the people who design software have to be pragmatic about the way information is organized. What that means is that whether you’re building a CRM or a notes app you’re following this principle:

The more precisely we know what to use a piece of information for, the more precisely we can organize it.

In the case of a CRM you know that you’re going to use the information as part of a sales process. So in the first place, it’s got to be very important to record customers and record key details about those customers like:

- Their name

- Their address

- Where they are in the process of being sold

- The potential value of the deal

Because it’s possible to know in advance how the information is going to be used, it’s possible to create atomic objects like “customers” where we collect standardized pieces of information and then relate that information together in a uniform, universal, hierarchical way.

Notes, in the broadest sense, are not like this. They cannot be depended on to be part of a standard, well-defined process. A piece of information is a note when you have only a vague idea of how it will be used. Or, when you have one idea of how it will be used, but you think there may be many more ways it could be used down the road, too — it’s hard to predict.

Should the book note go into the notebook that tracks all book notes? Or should it go into the project that I’m currently working on that relates to it? Or should it go into a notebook that tracks all of the authors I’m reading? Or, because it’s about software design, should it go into the software design folder?

I might want to use the note in so many different contexts and places, it’s very hard to know the one precise place it should be filed. Many organizational structures might work, and it’s hard to know which one to pick.

4

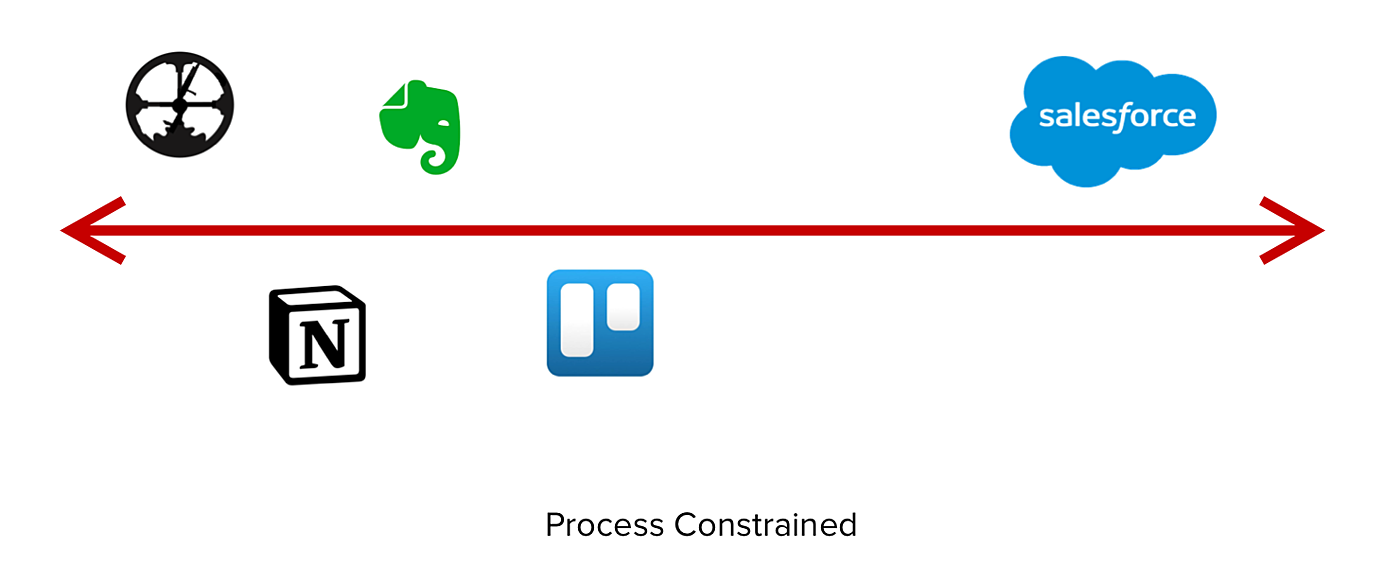

If we zoom out we can use this pragmatic insight to map every piece of software on a spectrum:

On the left hand side are notes apps — these are apps that record and process information as part of an undefined process. On the right hand side are things like CRMs — these are apps that enable their users to record and process information as part of a well-defined process.

The more well-defined the use-case the more rigid and hierarchical, the more deeply the organizational structures we use try represent the world.

The less well-defined the more flexible we get. The further to the left of the spectrum, the more we use many different types of organizational structures for the same information, and our hierarchies look more like networks than trees.

5

Now let’s get back to Tiago and Conor.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!