In the 1975 classic 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon croons:

The problem is all inside your head, she said to me

The answer is easy if you take it logically

I'd like to help you in your struggle to be free

There must be fifty ways to leave your lover

For Paul Simon there might be fifty ways to leave your lover, but, for Andrew Wilkinson, there are 50 ways to say no to meetings he doesn’t want to take.

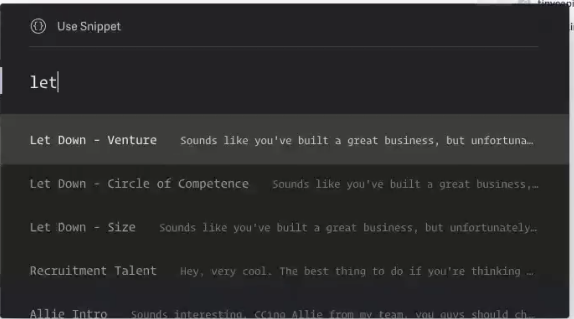

I know, because I’ve seen his templates. He calls them “Let Downs” and he has one for every occasion:

- When a person doesn’t fit into his circle of competence.

- When a person’s business isn’t large enough.

- When a person is trying to build a venture scale business.

And those are just the most common ones.

Andrew is a partner at Tiny where he starts, buys, and invests in internet businesses. Over the last few years he’s built it into a thriving collection of companies — over 30 with about 600 employees collectively.

What Andrew has built is fascinating because he’s turned himself into a people router. He takes people who arrive in his inbox, and gets to decide where in the Tiny machine to put them. If he does that job well the machine will grow — like magic.

His job is to turn people into opportunities.

But here’s the conflict: even though his job is all about people, he doesn’t like to be on phone with them too often. He only likes to do 2-3 meetings a day — which is surprisingly few for a guy with 600 employees.

That’s where the templates with a hundred different polite ways to say, “No” come from.

But this habit of saying no spreads beyond his inbox. He’s really set up his whole life by saying no. He’s said no to venture capital, he’s said no to living in Silicon Valley, and at his company he’s used delegation to say no to anything that will require him to do work that he doesn’t want to do.

In short, he’s said no to anything that doesn’t fit into his vision of success — and it’s working pretty well.

He’s the CEO of No. Which seems to leave a lot of room for the life he’s said yes to.

So, hop on the bus, Gus — let’s see how he does it.

Andrew introduces himself

For the last few years, I’ve been a partner in Tiny. We buy mostly bootstrapped and profitable internet businesses from their founders. We’re committed to holding them for the long term, maintaining their culture, and growing them sustainably.

We’re up to almost thirty businesses, and somewhere around 600 employees.

I get to wake up every morning and not have too much of a day job other than buying new businesses and talking to our CEOs — so that’s pretty cool.

I try to optimize for happiness

I’m not one of these ‘change-the-world’ entrepreneurs. I really try to keep my goals much more humble, and here's why.

For the ten years that I ran my agency MetaLab, I had the chance to get really up-close and personal with a lot of founders. I had a front-row seat for all of their successes and failures.

What did I see? Most of them were miserable. They weren’t optimizing for happiness. They weren’t enjoying their lives. They weren’t sleeping. Their marriages were suffering.

It really made me question whether I would be willing to sacrifice my home life — be a bad dad, get sick all the time, lose my marriage or my health — just to achieve something ‘huge’.

Obviously, there are incredible innovators out there, people like Elon Musk and Steve Jobs. But my view is that, at the end of the day, if I don't do the amazing paradigm-shifting things — someone else will. That's just how ideas work.

So I don't worry too much about being innovative.

What I do instead is try to structure my life around how to make myself happy, and how to make my family happy.

Now that I have enough to do that, I get to ask how I can make my employees happy, and make my community happy. That means continuing to grow the organization, because that lets us promote people and pay them more.

Ultimately, building more freedom means we can really build up a wall between ourselves and the things we don't like doing.

I’m a human router

In my job at Tiny, I’m really just a router to get opportunities to the right place. That means people come in to my life through email, and it’s my job to figure out where they fit (or if they fit.) It’s all about the power of connecting people.

My role in the business at this point is to continue to meet people and represent our brand in public, on Twitter, and through my writing. That means opportunities come in, and we have a whole machine to process them.

Those opportunities can come in the form of a client who wants to work with one of our services businesses, or it can be a business that wants to sell to us, or an executive who wants to work with us.

Seeing so many opportunities comes from how I spent the early part of my career.

The first few years of my career, I was a relentless, never-eat-alone networker. When I traveled, I made sure to go for lunch and coffee with as many interesting people as I could. I reached out to tons of people on Twitter, too.

I really enjoyed doing this. It’s partly because I’m extroverted, but I guess I’m a collector of interesting people and interesting ideas. This allowed me to get exposure to a lot of both.

For me, networking was never about asking people for anything — I was fortunate enough to have these independent, profitable businesses, so I wasn’t ever raising money, and I never needed favors. I just built friendships with people at the same time as I was building a reputation.

I built a really good Rolodex — to the point where now, if someone is looking to connect with a person at a particular company, I almost always know someone there, or how I can get in touch with them.

Email is my inbox for everything

Almost everything I do in a workday — all that routing I’m talking about — happens via email. You know, I’m on a Mac Pro right now, with the 30-inch screen, and I have no right to have this computer because at the end of the day, it’s just Superhuman and my calendar that I use for work — that's it.

Financial statements and analytics, communication with our CEOs, all of our deals and M&A — it all flies through my inbox.

My system is incredibly simple. I don’t have a to-do list, other than my inbox. The way I handle my inbox has changed a lot over the years, but I’ve settled on Superhuman.

Superhuman has been both a blessing and curse. It’s a blessing because it lets me get through my inbox without cognitive overload. I didn’t realize how slowly everything had been moving until I started using Superhuman.

On the flip side, it created some negative behaviors for me at first. I became addicted to the game of getting to inbox zero. So I’ve had to put some guideposts in place to keep me from spending all day in my inbox and achieving nothing other than sending a lot of emails.

I use Mailman as my email gatekeeper

We’ve invested in Mailman, a Gmail plug-in that has been super valuable in changing my email behavior. The key thing Mailman does is space out the delivery of my email so I only get it at designated times.

For me to be able to focus — to do that ‘deep work’ that Jason Fried talks about — I need two to three hours of time where I know there's not a bunch of email coming in. So I have Mailman set to deliver my email at 6:30am, 7:50am, 10, 12:30pm, and 2:00.

That way, if I send out a whole bunch of emails, I won’t see the responses as they’re streaming in, so I don’t check email constantly and end up staying in my inbox all day.

It’s crazy what a difference it’s made. My inbox is just so much more chill. And I probably spend one or two hours a day on email now, where I used to spend four or five.

Certain VIP emails I always want to see immediately, and I don’t ever want them filtered out or delayed — internal stuff, email from an important investor or our WeCommerce teams, anything from DocuSign or RightSignature.

Annoying stuff — emails from people I haven’t talked to before, or newsletters and spam — gets kept out of my inbox until it’s all grouped into a digest that comes once a day.

You can also set a Do Not Disturb. From 4:00-6:00am, I don’t want to get any email at all because I’m with my kids. I used to constantly check my email all night, and if someone sent me a bomb, I’d not sleep, or freak out.

Mailman has basically helped create much healthier behavior for me, and email isn’t as much of a nightmare as it used to be — I stay focused on important stuff, and don’t get bogged down in the game of getting to inbox zero.

The nuances of saying no

When I’m dealing with emails, sometimes I just have to refuse people’s requests.

At first, I’d say yes to everything — meetings are really valuable when you’re starting off. But I reached a point where I was letting myself get scheduled on six to eight hours of phone calls a day. And when I looked at them, I couldn’t identify what the positive outcomes were — and more importantly, I didn’t enjoy doing it.

If I did everything like that, I would end up sacrificing my own life for other people. And that’s just not what I want to do, so I started to say no a lot.

But saying no in all of its forms — be it refusing a request, firing somebody, cancelling something, or dealing with sunk cost fallacy — is really, really hard. It’s emotionally burdensome.

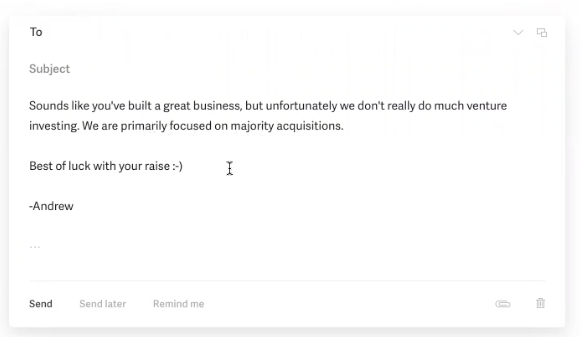

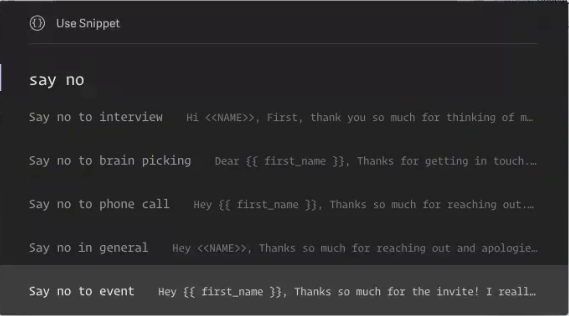

So I try to be very deliberate about how I have those difficult conversations. If somebody makes an email request that I need to say no to, I have a wide variety of response templates in Superhuman that allow me to do it in a nice, polite way.

For example, if somebody emails looking for us to invest in their startup, I have a short, friendly response template email ready to go that explains that we don't really do venture investing.

It’s short, but it's friendly.

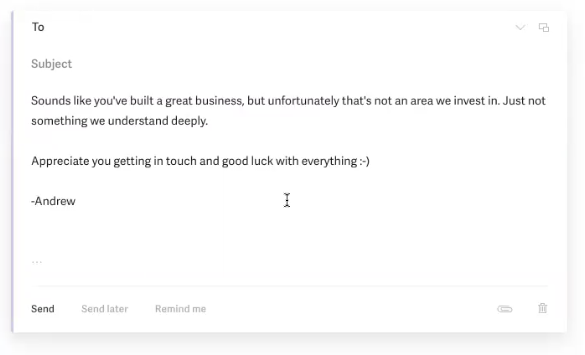

If a request falls outside of our circle of competence, the template says, “Hey, this is something I don't understand, so I can't invest in it.”

I have a bunch of these different ways to let someone down. For example, if I get a request from a business that's too small, it’s 'Sorry, your business isn't big enough'. Or from somebody wanting to pick my brain — ‘Thanks for thinking of me, I’m very flattered; can I offer some of my writing as an alternative?’.

There's actually a big library online of all the different ways to say no — they’re just gold. I’ve spent a lot of time evolving and dialing in these templates for my own use, and it’s been super useful.

I’m pretty hard to get a meeting with

For the emails that I don’t say no to myself, or route to somewhere in the organization, I’ll cc my assistant. Together, we’ve put together a coding system to mark the priority of requests that come in.

A ‘1’ is very important and urgent, while a ‘3’ might be a request for a podcast interview or something like that, which can be scheduled for a few weeks or months out.

When it comes to scheduling calls, my assistant knows that my schedule has to stay pretty clear, with a good deal of slack in it, because unexpected problems inevitably come up with one of the businesses. If that happens, my day can easily spin out of control and become horrible — and force me to cancel or reschedule calls.

Sometimes people get angry if I have to reschedule a call due to an emergency — especially if I can’t get it back on the schedule immediately — but I always ask if they really want to talk to me when I’m stressed out. It’s better for me to reschedule further out so I’m not talking to them in the middle of a bad day.

This is about protecting my own sanity, and the whole purpose is freedom and not hating my life.

If it makes it onto my calendar, it’s important

On a typical day, I try to keep my mornings clear until 11. Before then, I’ll try to get some exercise, like playing tennis.

Then I’ll do maybe thirty minutes to an hour of email, when I’ll try to clear up my inbox and address any bombs that might have come in.

I keep three calendars — Work, Leisure, and Family. My work calendar is the blue, and what’s on here are the key events — the hard landscape of things I will be in, no matter what.

Starting around 11, that’s my prime time for meetings and phone calls. But here’s the thing: I can only talk on the phone for so long before I’m brain dead. I’ve found that my limit is about two hours a day.

Any more than that, and I don’t perform as well on calls, and I’ll be irritable and tired when I get home — basically, I’m miserable. So I intentionally try to keep calls within that two-hour window.

I usually fast during the morning up until I'm done with my meetings. I started fasting as a way to deal with acid reflux, but it’s turned out to be a huge productivity hack for me — it turns out that I think a lot more clearly before I eat.

A whole bunch of studies over the last five years say that we were evolutionarily designed to fast. If you think about it, our hunter-gatherer brain probably needed us to be sharper while we were out hunting.

So I do a sixteen- or eighteen-hour fast every day. I usually eat my first meal around like 12:30 or 1, and then the afternoon is kind of a write-off, to be honest. I might do some email or go for a walk with my business partner.

How I say no to working all the time

A lot of people might be surprised by how empty my calendar is. Many CEOs seem to believe they have to wear themselves out working 9 to 9 — they torture themselves, basically — but I think you can run a large company in two to three hours a day.

Almost any CEO can get to that point, but it’s essential to have the right executive team, and it relies on an incredible amount of delegation.

The last couple of years that I was CEO of MetaLab, I didn't get on the phone with clients, and I wasn't doing a lot of sales. I wasn't focused on product delivery, and I wasn't doing hiring, other than key executives.

At the end of the day, it comes down to being a leader who sets the high level strategy, goals, and culture.

One of the mistakes that a lot of entrepreneurs make is they include themselves on the team. I think you're a coach and you should be standing on the sidelines — cheering on the team, moving the right people in and out, and changing strategy as you need to.

Personally, I think it’s a lot easier to run a company than people think — it just takes a while to figure this out. And the only way you’ll get there is by going through it. I know this because I’ve made all the mistakes!

The ultimate productivity hack

Delegation is the biggest thing that keeps my calendar relatively clear, and makes my life so much easier now.

I only make a few key decisions a month, because I’ve delegated out a lot of the day-to-day decision-making. With that went a lot of the stress.

In the early phase of running our agency, I was very motivated because I was worried about money — paying for dinner, or for rent, or payroll.

But once I finally had money, I became incredibly demotivated. It was like I was just coasting, and I didn’t care to put in the extra effort to make another million bucks.

So I hired a CEO, and I incentivized him by basing a lot of his pay on how well he grew the business. It was almost like I outsourced my motivation to someone else.

It's hard to replace yourself like that, but that person's out there.

I struggled with this a lot at first. I’m cheap, so I would hire junior talent, and then I’d manage and grow them.

But I’ve learned that the most efficient way to source talented people isn’t to hire for moxie and potential. It’s to find the person who’s done the job before, and who’s done it at double the scale.

When you hire them, they’re going to cost a lot more than the junior people, but they’re going to do the job, and do it well from the start. Pay up. The best people are always worth paying for.

And they just make your life so much less stressful.

I put my family first

I'm past the milestone of feeling proud to be an entrepreneur. I've made enough so that money has stopped being as much of a motivator as it once was.

So where does my sense of purpose come from? It all became clear to me when I had my son when I was 31. It was incredibly meaningful and it gave me a lot of clarity in my life.

I used to come home and work in the evening. I used to work on the weekends. Now, I’m so busy with kids and work that I don't even have the time to have existential crises anymore —which is very, very nice.

Sure, I miss having an open weekend schedule — reading the New Yorker and sitting in a cafe for four hours and doing whatever I want — but having kids is a million times more rewarding and I recommend it to anyone.

Now, my happiest time of the week is Saturday morning. My wife usually either sleeps in or just wants to hang out at home, so I take my oldest son and we go to the farmers’ market together.

I love watching this little person who doesn't have full consciousness yet, but who’s just so fully present — like he's a little mini-monk or something. He’s not thinking about the future, he’s not anxious — he’s just enjoying the moment.

There's nothing better than getting to relive your own childhood — and I never want to say no to that.

This post was co-written by Dan Shipper and Kieran O'Hare.

Introducing: Free Radicals!

We welcomed a new newsletter into the Everything bundle this week: Free Radicals. It’s a collaboration between our team and Sherrell Dorsey, founder of The Plug.

Free Radicals is a limited series celebrating those who embody leadership in this moment. Each edition features a conversation between Sherrell and a leader in tech, focusing on equity, advancement, and progress.

You can read it here!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This is one of the best CEO life lessons I have ever read. I keep coming back at it in the last weeks, and today I decided to scroll down to the comments. To my surprise, there was none - but I immediately grasped why. It's so much to learn here that you always finish like it was the first time you read it. Thank you very much for this one.