Hi all! Dan here. Today’s Member’s Only post is written by superorganizer-extaordinaire Adam Keesling. I served as the editor. I’m super excited to have Adam helping out around here, and I think you’ll love what he wrote. Make sure you say hi to him in the comments!

Forgetting what you read?

If you’re anything like me, you’ve experienced a progression of reading that looks something like this.

After experiencing the joy of learning for the first time — when I learned something on my own — I got addicted to knowledge. I read a bunch of books. Everything I could get my hands on.

After several weeks and several books, I looked back on the first one I read. What was it about again? I couldn’t remember anything other than the title and one or two central ideas.

“Sapiens? I loved that book. Great history of, uh, humans. Agricultural revolution was 12,000 years ago and it changed everything. I know, I know —it’s crazy.”

What to do about this? My first solution was active reading.

Active Reading

Active reading allows you to engage with the material you’re consuming at a higher level. A few common techniques:

- Annotate in the margin to summarize points or raise questions

- Highlight or underline important passages

- Compare what the author is saying to other ideas

There’s a difference between knowing about something and actually knowing something, and active reading encourages the latter. Playing with the material like this not only improves retention, but it also helps you evaluate claims better.

As Superorganizers readers, many of you already participate in some form of active reading. And you might even go one step further by keeping all of the notes you take in a database like Evernote or Notion.

This is great! But I want to challenge you: could your note-taking system be even better?

If you’re anything like me, Notion and Evernote leave something to be desired. They aren’t ineffective, but they don’t feel magical either.

First, it’s hard to find what you are looking for. Thoughts in our brain are associative and it can be hard to find what you are looking for with a keyword search. Search engines aren’t advanced enough yet to detect intention, so we have to make connections on our own.

Additionally, Notion or Evernote archives become littered with clutter pretty quickly. While writing everything down does improve your thinking, you probably don’t want to keep every miscellaneous note and clarification in your long-term notes.

Finally, it’s just hard to make connections between notes. Searching in Evernote and Notion might return all the articles that mention the word “decision making”, but that’s only partially useful. What else were you thinking about when you read that article from two years ago? Do concepts from that article connect to a different article you read a year ago? How do you nurture those connections?

Enter: Zettelkasten.

What is a Zettelkasten?

The Zettelkasten method is a better way to take notes. The basic idea is this: take notes on cards, review them, then link them together. That’s it. It’s not a complicated system, but it is powerful.

Over time, this builds an intricate network of your best ideas. As the database gets larger, it even starts to mimic a conversation partner.

The method was developed in the 1960’s by Niklas Luhmann, a prolific German sociologist.

And prolific he was.

During his lifetime Luhmann produced over 70 books and 400 research articles using over 90,000 notes that interweaved sociology with topics like biology, theology, systems theory, computer science and many others. (You can read more about his work here.)

What made the method so effective?

What Makes the Zettelkasten Method Effective

The Zettelkasten method makes two things super easy: finding an entry point to vast database of notes, and making surprising connections between notes. You always have somewhere to start and you never know where you will end up.

The Zettelkasten has an index that lists out all of your tags (and cards associated with each tag.) So if you don’t begin your research with a note in mind, you can glance at your index to find inspiration. You don’t have to brainstorm ideas from scratch and can instead depend on your previous work.

The other notable feature is that notes in the Zettelkasten are single ideas connected to each other though direct links and tags. Once you get started on a thread, the system will naturally guide you to new territory.

Creating a Zettelkasten is like creating an intellectual time machine. You enter in your current mental state and the machine carries you across time to talk to yourself in the past and future.

With this method, you can summon ideas on-demand. You actually use your notes because they are both accessible and permanent.

Instead of relying on your human brain or struggling to dig out a page from your Notion graveyard, build your own Zettelkasten.

How the Zettelkasten is Structured

There are two sections to a Zettelkasten: Inbox and Notes Archive.

The Inbox is a section for cards that are written out, but still need to be sorted. This is where you are going to put your notecards when you first create them.

Once cards have started to build up in your Inbox, you’ll set aside some time sort and organize them into your Notes Archive. The Notes Archive is the heart of the system, the intertwined network of your past thoughts.

Luhmann would move his cards every evening, but there’s no hard and fast rule for how often to tend to your Inbox.

Getting Started With Paper Notecards

To create a Zettelkasten, the only materials you need are 3x5 paper note cards, a writing utensil, and a place to store everything (a small box or file will suffice).

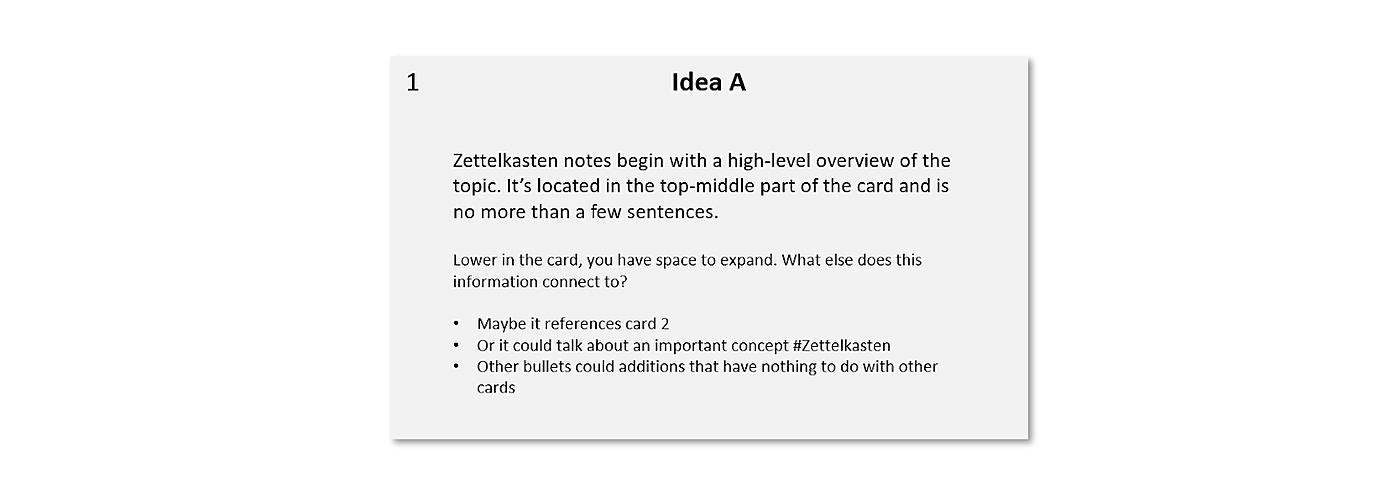

Here’s how it works: when you come across an idea, take out a notecard and write it out in your own words. Capture the essence in a few sentences and make sure there’s only one idea per notecard.

The idea can be anything and can come from anywhere. Don’t worry too much about which idea to write down either. You can write down as many as you want and organize them later — and you can even add new cards to the mix after the fact. The Zettelkasten is flexible enough to handle it.

Once your Inbox starts to fill up, it’s time to move your cards to your Notes Archive.

Inbox to Archive: Identifier

Once you have a stack of notecards filled with ideas, the next step is to organize them. At first, your card might look like this:

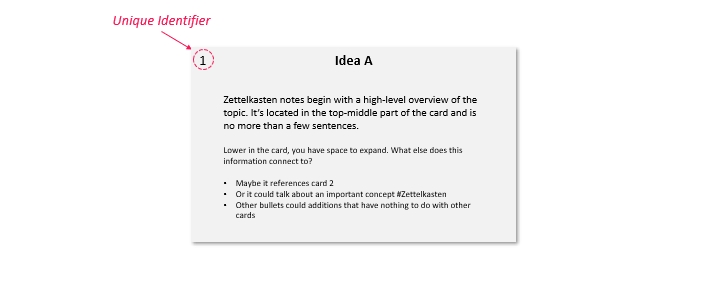

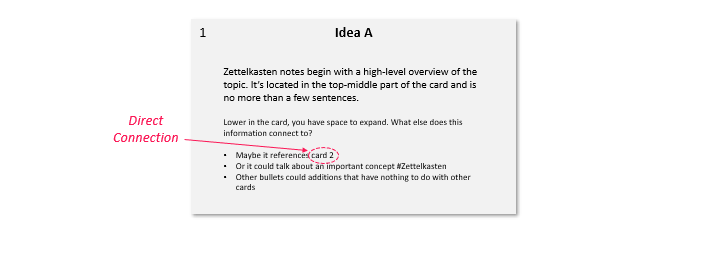

Then you’ll want to label the card so it looks something like this:

We added three important things: a unique identifier, direction connections, and tags.

Let’s start with the identifier. The only thing that is truly required for a notecard is a unique identifier — an address, if you will. Luhmann put his numbers in the top left, but consistency is more important than the exact location.

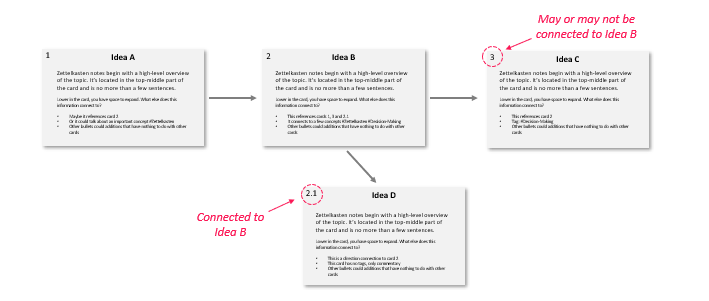

Luhmann came up with a numbering system that not only acted as the identifier, but also allowed for branched development. Let me explain.

Label your first card “1”, and then label your second card “2.” For your third card, you have the following options:

- 1.1 (if it connects to the first card)

- 2.1 (if it connects to the second card)

- 3 (if it’s a new topic, or if it connects to the second card)

This system allows you to connect lots of individual thoughts without coming up with those thoughts at the same time. Idea D was a continuation of Idea B so its number is “2.1”.

This process continues with the second-tier branches. If you number cards 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, etc., a new card might connect to 2.2 so it would be labeled as 2.2.1. This is the key feature that allows new notes to enter the Zettelkasten while still meaningfully interacting with the existing system.

(For those who are curious: the reason whole numbers might not connect to each other is because there has to be a spot to introduce completely new topics. It might be the case that 3 extends from 2, but it’s fine if 3 is completely new ground.)

In addition to numbering cards, we also have to connect and tag them together. This is where the Zettelkasten really stands out as a note-taking method.

Inbox to Archive: Connections

Direct Connections link one note to another. All you have to do is go through your existing Notes Archive and connect your new notes to existing notes.

The only (sorta) hard part is figuring out which notes to connect. A few questions that can help you decide:

- What’s the next thing you want to include if you explained this topic to someone?

- What would you include for an outline for an article or paper?

- What connections is your brain naturally making?

Returning to our original card, we see a connection to card 2:

In this example there was only one connection, but more likely than not there will be several connections (that span the entire Archive) that are built up by revisiting cards over time.

The advantage of this is that two notes may be spatially far away but topically similar, creating surprise when you go back to review them. This surprise is a key element of the system: it branches and connects in ways that you might not expect, which helps you come up with new ideas.

Inbox to Archive: Tags

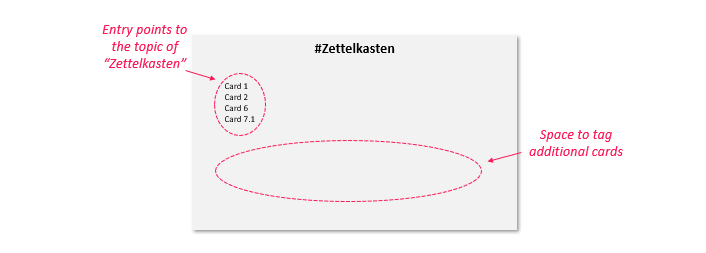

Luhmann would also create cards that were broad entry points into a topic. The cards are called “Index cards” and the topics are called “tags.”

These cards are helpful because you might have an Index card titled “Biology” that links to 25 different cards, each of which is a starting point for biology. Referencing these cards is a quick way to point at a topic without needing to connect to an individual idea. It’s an excellent solution to writer’s block.

Tactically, you should put your Index cards in the front of the Notes Archive or in a separate section altogether. If the topic was Zettelkasten, you would put that at the top of your Index card and list out any other cards that were entry points into the topic:

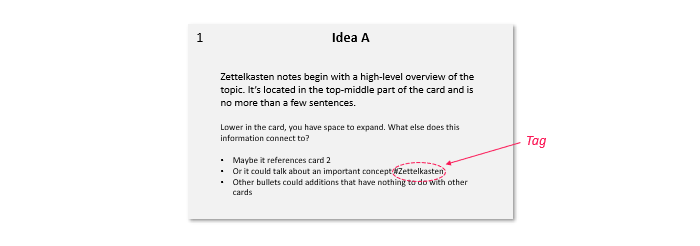

I also recommend adding the tag to the idea cards. This way, you can pop back up to the Index card if you need a new perspective:

Biggest Benefit? Better Writing

There are a lot of ways to use your Zettelkasten, but I think the best application is writing. It helps with a bunch of things:

- Creativity: connecting far-reaching notes that you wouldn’t have come up with on your own.

- Clear writing: writing notes in your own words helps you clarify your thoughts.

- Outlining: having trouble organizing your thoughts? Pick a path through the linked notes and use that as an outline.

The Zettelkasten method is fun once you get the hang of it. And the best part is that in compounds in value over time — each new note might add dozens of links over the course of its life.

Did you like this post? Are you using Zettelkasten already? Want us to cover how to build a digital Zettelkasten for yourself? Let us know in the comments!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This structure would have worked well within Lotus Agenda (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotus_Agenda) which was later incorporated into Lotus Notes. Not sure how easy Zettelkasten could have been built in Notes. Also, the indexing and associations makes me think of Jeff Hawkins work around the brain.

Wow, such a simple and beautiful guide to Zettelkasten!. Read many writings about it but no one laid the system down as simply as this.