In this installment of Playtesting, Alex Duffy shows why games might be the smartest approach to AI training right now. As the cofounder and CEO of Good Start Labs, he’s been exploring how game environments can improve AI capabilities across unexpected domains. His latest finding is surprising: Fine-tuning a model on the strategy game Diplomacy improved its performance on customer support and industrial operations benchmarks. Read on to learn why games generate the kind of data and behaviors that make AI better at the serious stuff, and what the Every team has learned from classics like StarCraft.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

It’s my job to make AI play games. One board game we’ve focused on at Good Start Labs has been Diplomacy, a World War I simulation reportedly played by John F. Kennedy and Henry Kissinger. There’s no dice and no luck. As everything shifts around you, all you can rely on are persuasion and strategy.

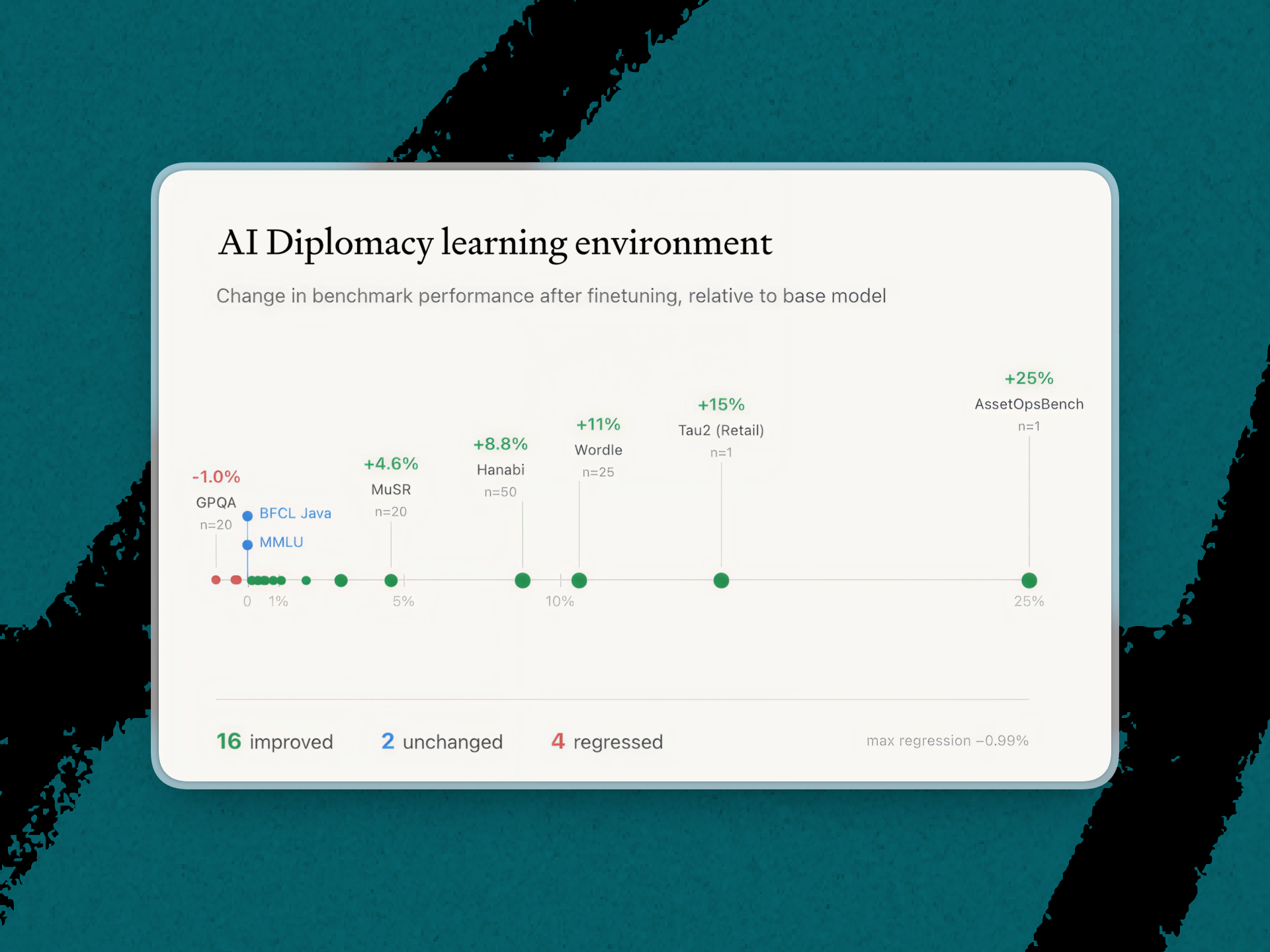

When we fine-tuned the Qwen3-235B model—an open-source model developed by the team at Chinese cloud computing company Alibaba Cloud—on thousands of rounds of Diplomacy, we found an over 10 percent improvement in performance on other games such as the card game Hanabi and word game Wordle. But we were encouraged to see that these improvements translated to other realms. The fine-tuned model also did better on Tau2, a benchmark that tests how well AI agents handle customer support conversations, and AssetOpsBench, IBM’s benchmark for industrial operations like equipment monitoring and maintenance.

It’s not a big leap to believe that improvement in one game could boost the model’s performance on others. But how does understanding WWI strategy make a model better at helping someone change their airline reservation or monitor equipment? Simple: Games reward specific behaviors. When you get good at those behaviors, they show up elsewhere.

When I asked my colleagues at Every what games had taught them, everyone had similar experiences. “StarCraft taught me how to cook,” Every’s head of platform Willie Williams tells me, recalling the high-speed chess-like game. “You have things that take different amounts of time, and you want them to land at the same time.” Our senior designer, Daniel Rodrigues, learned English from Pokémon before any classroom. AI editorial lead Katie Parrott became a more systematic thinker from board game mechanics and applied it to designing AI workflows.

This transfer of skills from games to other domains works for AI, too—and we can measure it. Diplomacy trains context-tracking, shifting priorities, and strategic communication. Customer support, where information is often incomplete and requests shift, needs the same capabilities.

We trained our model on Diplomacy in a reinforcement learning environment where you can clearly score whether the AI did something right. Labs are racing to build these kinds of environments because they do something that feeding the models static data can’t: They give models feedback on their decisions, teaching them to strategize, not just recall facts.

When you train a model on text from the internet, it learns to predict words. If you train it in an environment with goals and feedback, the model starts to develop skills that look remarkably like strategy. It’s a glimpse of where AI training is headed: less scraping the web, more learning by doing.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I'm reminded of the way animals, of many species, learn to be adults and succeed at real-world tasks, by playing. Play provides rules, guardrails, constraints, and instant feedback - whether it's an online game, or a lion cub getting cuffed and dust-rolled by its dad for biting him a little too hard. This is how biological brains are trained, too. So it's gratifying, and encouraging, to see it work for AI models. What it leads me to is, "What other real-world (human or animal) training models can be applied in some way to AI training?" What else is there - categorically different from the static data and game playing approaches? What could a quick scan of developmental psych - child development, for example - yield?

@semery this is EXACTLY the thread I'm so interested in pulling, thanks for the comment

Thinking further on this... I wonder how AI would be improved if LLMs also learned to do complex physical things, embodied through robotics. Could they learn to play the guitar? To master juggling? These also have cultural and aesthetic aspects. There is a different sort of variability and feedback from physical reality - different control needed than for words, numbers, etc. And it's the learning that is the key, not being taught. They would need feedback, certainly, like a music teacher would provide. Juggling provides its own feedback... If the AI had to iterate on the use of the robotic device to perform the difficult task - a task with finesse, what would that extend to in other spheres? And once it learns on one device, it could be challenged to learn it over with another interface, perhaps one that's even more challenging. More difficult instrument, more difficult objects to juggle, less cooperative or adjustable robotics.

Maybe much of what this teaches humans, persistence, patience, grit, isn't "learnable" by AIs, because they have seemingly infinite resources. To counteract that, maybe (as in games) there should be some artificial deadlines or goals set. The experiment might be interesting...