When I was coming up in tech, the conventional wisdom was that working at or investing in software companies was a great way to make money, while doing so with companies that took on scientific risk or produced hardware components were a wonderful way to lose every cent to your name. This has always struck me as, you know, wrong, which is why this piece by venture capitalist Leo Polovets resonated with me. He takes a data-driven approach to understanding how deep tech companies can produce superior financial returns. If you’re on the fence with your career—perhaps facing temptation to do something relatively safe in B2B SaaS—take this piece as a rational encouragement to dream bigger. —Evan

I’ve been a venture capitalist for nearly 11 years. While most of my investing career has been focused on B2B SaaS with Susa Ventures, two years ago I decided to try my hand at deep tech. So I started Humba Ventures, which leads pre-seed and seed rounds in deep tech investing—sectors like robots and manufacturing, climate and energy, and defense and security.

Historically, VCs have stayed away from deep tech because it’s considered a hard industry to build in. Deep tech startups tend to have significant science and engineering risk, and it’s not always guaranteed that the products they plan for can actually be built. Compare that to SaaS, where there is rarely a risk that a product can’t be built. Instead, the risk is whether the product is worth building, and whether anyone will pay for it.

Other factors have helped fuel the stereotype that deep tech is a difficult sector. In the past, there hasn’t been much follow-on funding for startups or successful predecessors to hire from. And a few outlier companies have created the reputation that deep tech companies burn a lot more than their peers.

But these stereotypes are wrong. In fact, now is the best time to invest in deep tech companies. There are lots of macro tailwinds fueling this phenomenon, including physical solutions that are needed to reduce climate impact, bring manufacturing back to the U.S., and defend ourselves against global threats. And as traditional startup sectors face cutthroat competition, with generative AI dropping costs of building new software products, deep tech’s higher barriers to entry can allow any team willing to surmount them to reap huge rewards.

Not all my beliefs are macro. I’m an engineer and data guy by training, so I decided to dig into some PitchBook data. And the data has said the same thing. Deep tech is the best place to invest in and build right now. In this piece, I’ll cover three misconceptions about deep tech in detail

Aren’t deep tech companies more capital intensive than traditional tech?

On average, no!

Look at every list of “most funded companies.” They are almost exclusively traditional startups, in areas like marketplaces, fintech, and social networking. These are companies like Uber, WeWork, and Oscar, which spend orders of magnitude more than most deep tech businesses.

When the barrier to entry for building a product is low, companies need to execute quickly and pay heavily for customer acquisition. This can quickly get expensive. Deep tech companies typically face less competition, so they can spend more of their resources on developing unique IP than on paying for customer attention.

Additionally, deep tech companies have access to grants and other non-dilutive funding, as well as larger contract sizes. Take the defense industry. The Department of Defense awards multiple eight-nine-figure contracts daily. Any startup that captures a few contracts of this size is basically a $1 billion-plus-valuation company.

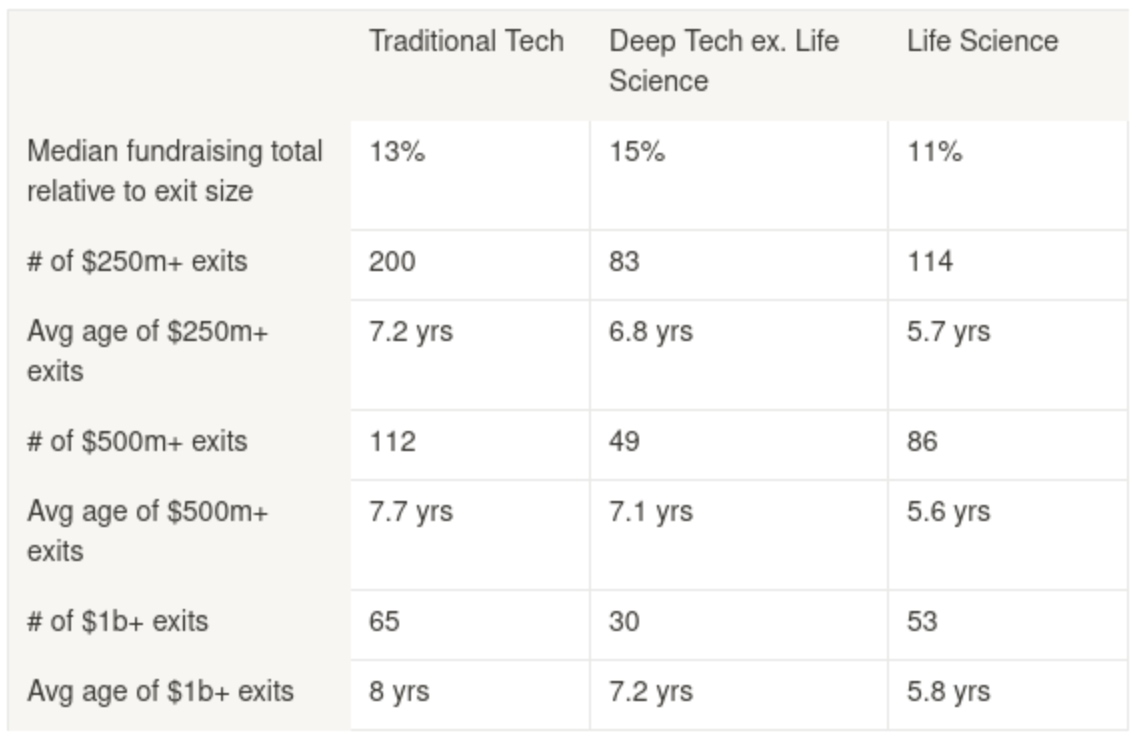

The reality is that both traditional and deep tech companies are similarly capital intensive. Here’s a summary of PitchBook data for companies founded since 2010 in the U.S. and Canada that have had exits greater than $250 million:

Source: Pitchbook.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

You produce amazing articles of interest to professionals who are in software development or financial investing in technology companies. That's such a small slice of the total industrial, and professional pie and I wonder if this is the niche Every wants to claim as their core?

Please write more about deeptech. Like new ideas, startups, technology, etc. This is article is an amazing insight into a risky but a bit untapped area of making career.