Earlier this year, Willem Van Lancker argued that productive friction—the struggle of learning through failure and critique—is what AI threatens to take away. Jack Cheng picks up that thread and pulls it further: When AI makes surface creativity easy, what becomes valuable isn’t just the struggle, but the specificity of your lived experience. Call it “thisness”—the details only you can bring to your work. As creative fields shift faster than ever, personal experience is your most durable edge.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

“The disease you have to fight in any creative field,” says the musician Jack White, is “ease of use.”

Though White asserted this in 2008, today’s AI startups and stalwarts touting creative democratization might take heed. His insight is that creativity is fluid—and aligned with difficulty. When technology changes what’s difficult, what’s creative changes too.

I first came across the quote as a young advertising copywriter in New York City. Since then, I’ve worked across a number of creative disciplines. I co-founded and led design and front-end development at a product studio whose clients included Napster co-founder Sean Parker. I launched one of the first literary fiction projects on Kickstarter and wrote two award-winning children’s novels published by Penguin Random House. In 2023, I completed a postgraduate architecture diploma, and last year I built an iOS notes app using the first wave of AI coding tools.

I’ve seen over the last 17 years what’s difficult, and thus valuable, in these creative fields. As I now watch generative AI infiltrate each of them and smooth away some of those difficulties, I’m also starting to see what might stay difficult and grow more important in the years to come.

Make your team AI‑native

Scattered tools slow teams down. Every Teams gives your whole organization full access to Every and our AI apps—Sparkle to organize files, Spiral to write well, Cora to manage email, and Monologue for smart dictation—plus our daily newsletter, subscriber‑only livestreams, Discord, and course discounts. One subscription to keep your company at the AI frontier. Trusted by 200+ AI-native companies—including The Browser Company, Portola, and Stainless.

Creativity is a metagame

One way I think about the moving target of creativity is through the lens of the competitive gaming term “meta,” short for “metagame.” The meta is the current dominant or “best” strategy among a game’s community. It’s the game around the game. As new updates roll out, characters and items are introduced or amended, and new tactics and countertactics are discovered, the meta changes.

In chess, the meta long emphasized attacking at all costs—until the late 1800s, when the first official World Chess Champion Wilhelm Steinitz reinvented the game with “positional chess,” which focused instead on collecting small advantages while your opponent attacked without purpose. Positional chess became the new meta, until eventually it gave way to even newer strategies.

Each creative field has, at any given time, its own meta. In hindsight, this appears broadly as movements or schools of practice. In Western art, realism gave way to Impressionism, which was succeeded by Post-Impressionism, then Expressionism, and so on. In the moment, though, an individual artist or group of artists might notice that a certain kind of art is becoming overdone, and respond to it by trying to make something new and different.

Here’s a writing example. At Every, we use an AI editor as extra eyes on the human-edited articles we publish. One thing this AI editor looks for is “tells” common to AI-generated writing (a poker term, if you needed any more proof of the game). If I write, “AI doesn’t make every hard thing easy; it makes some hard things even harder”—that’s what’s known as a correlative construction. Use them too much and they grow stale. It doesn’t matter if the author is a chatbot or a human being.

There was a time though, during the 2000s and 2010s, when AI tells like these could be hallmarks of effective non-fictional prose. Malcolm Gladwell’s international bestsellers The Tipping Point and Blink used a style of rhetorical questioning that mirrored a reader’s curiosity, and he deployed the phrase “it turns out” to emphasize counterintuitive findings. Gladwell wasn’t the first to do these things, but he was widely imitated, particularly in tech writing circles. When language models weighted toward this kind of technology writing then adopt it as the norm, the same rhetorical devices are no longer as effective. The “technology essay writing meta,” in other words, is actively shifting away from this style of writing.

The French essayist and poet Paul Valéry once described the future as something we enter as if rowing a boat, only able to see what’s in our past. So is good writing, a trail of em dashes and “here’s the thing”s in our wake.

The ‘Princess Bride’ dilemma

You might see the catch: If you play the meta and try to avoid these AI tells, then what you do to write around the tells might itself, if repeated enough, become the new meta—and soon after, the new cliche. So in anticipation, you try to write around those budding cliches, also anticipating that how you do so might eventually become its own cliche. Pretty soon, you’re the smart-aleck criminal Vizzini in The Princess Bride, going around in circles trying to guess which glass of wine your opponent has poisoned, thinking that you know that he knows that you know it’s not the one in front of you.

In centuries past, developing your own style was something that often required a lifetime of study. A painter might start by copying existing works by favorite artists before their own emerged as an amalgam; a trumpeter would learn to play existing songs before improvising or composing their own. As a writer, I had to have read enough books for my own writing not to come out sounding like the last author I read.

When generative AI quickens the creation of new styles, when it accelerates the meta, one strategy is to try to keep staying ahead of the game, to spin up new combinations more quickly than your competition. Having the resources to do so—more resources than your competition—is often one point of difficulty. Those with access to more capital can afford to run more of these experiments on cutting edge models.

But there are other, more durable, strategies. In The Princess Bride, the hero Wesley wins the guess-which-glass-is-poisoned not by participating in Vizzini’s mental acrobatics but by standing outside the circus. He knows what’s constant regardless of which goblet of wine is poisoned—that poison kills. So his strategy from the start is to be immune to poison.

That begs the question: What’s constant regardless of AI’s advancement? What other currently difficult things will stay difficult?

The folly of the perfect map

In the short story “On Exactitude in Science,” Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges describes an empire so bent on creating the perfect map that their attempts grow grander and grander, until the map becomes, point for point, the same size as the land it describes.

What I’ve come to realize about my own writing, and what I try to advise Masters of Fine Arts students about theirs, is that it’s better when it’s personal, when it’s a story that only you can tell, given who you are and the life you’ve lived. In the work itself, this often shows up as specificity, of a particular shade of blue, an acetate eyeglass frame smudged with finger oils, a miscommunicated longing—of what critic James Wood in How Fiction Works calls thisness, or “any detail that draws abstraction toward itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability.”

This thisness, this specificity knowable only from personal experience, is what readers pick up on, and what ends up making a story universal and relevant—not catering to what’s hot in the market at any moment. And in order for a language model to truly map this terrain, you would have to feed it your entire life’s experience, everything you’ve seen and heard and read and felt, a map as multitudinous as you.

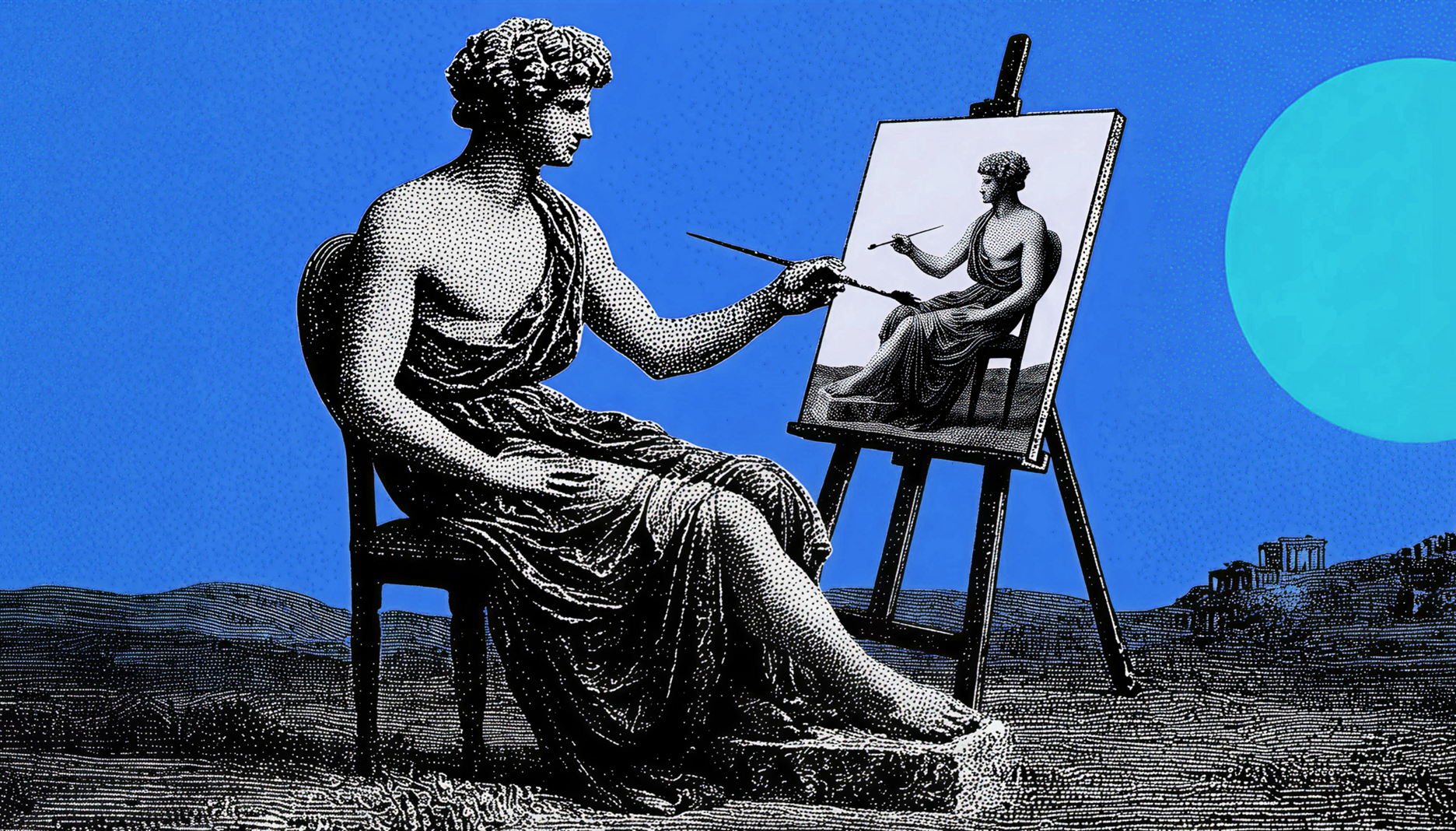

When it’s easier to mimic and create surface styles, what stays difficult—or maybe even gets more difficult—is matching surfaces with substance. Lucas Crespo’s art direction on this website, for instance, reflects our founder Dan Shipper’s deep interest in philosophy and history. The style is appropriately applied. It’s true to the context. It feels authentic—more authentic than if one simply threw similar images onto any other site simply because they looked cool.

The same goes for startups. When it’s so easy to prototype new ideas and spin up new products and businesses, and for others to do the same, I suspect more founders will find themselves asking: Why am I the right person to be building this thing? What about my personal experience do I bring to it that makes it more meaningful and true to who I am?

On knowing thyself

There’s also a way, however, in which generative AI can help make creative work even more personal. To me, the thisness described above requires a level of emotional vulnerability and safety. It requires honesty, self-awareness, and self-examination.

There are some topics and memories that are too difficult for me to face head on, because they’re embarrassing, or painful, or traumatic. I might struggle even to talk about them with a therapist because the aversion is so visceral. Sometimes the only way for me to explore them is with the distance of fiction.

In the case of my book, See You in the Cosmos, my 11-year-old character wants to launch his iPod into space, a goal that turns into an epic road trip on which he gains new insight into his late father’s experience. As I was finishing the book, I realized that I’d been asking the same questions about my own father’s experience when he first emigrated to the U.S.

Dan has been using AI with his journaling since the GPT-3 days, and I can see how this practice can be especially powerful for fiction writers. If I point my language model to a story in progress in addition to my journal, it could help me better understand the link between what I see in my imagination and the memories it was based on. The goal isn’t for the AI to write for me—that’s the fun part I want to do myself—but to sharpen my awareness of how it’s personal to me. That awareness would then let me bring even more of myself and my experiences to the story.

So if AI is even able to make this difficult thing less difficult, what’s left?

Toward a new (old) creativity

The architecture diploma program I completed in 2023 was based on the work of the late architect Christopher Alexander, who strove to create a more humane architecture that diverged from the novelty and provocativeness of his modernist peers.

While critics called him a “traditionalist,” Alexander experimented with computational modeling as early as the 1960s, and pioneered the use of residential gunnite—a form of lightweight concrete sprayed into plywood molds. But these tools and technologies were always in service of what he would later come to call wholeness—of creating beautiful spaces that first and foremost served the liveliness of their inhabitants, rather than the egos of the architects.

He was only traditional in the sense that his approach was similarly “un-self-conscious” as traditional cultures, in building not from a definite mental image of the outcome but adapting, growing, iterating, until a particular building or town or clay tea bowl felt as if it emerged to perfectly suit its context.

Students often come to the architecture program after disenchantment with standard art and architecture schools, and their emphasis on relentless novelty—whether explicit or implied. Alexander’s methods resonate to those seeking a greater purpose around their creative work, to those wanting not to chase the next new thing but instead bring about what’s needed and honest, what’s right and supportive of human life in whatever particular context.

Rather than a creativity of newness, or even difficulty, it’s a creativity of aptness. And in a world of generative AI, it feels like the future.

Jack Cheng is a contributing editor at Every. He is a creative generalist, multimedia producer, and the author of critically acclaimed fiction for young readers. He writes an occasional newsletter called Sunday.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora. Dictate effortlessly with Monologue.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

For sponsorship opportunities, reach out to [email protected].

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Love this: "Rather than a creativity of newness, or even difficulty, it’s a creativity of aptness."