By day, Tyler Okland is a head and neck surgeon at Stanford Hospital. By night, Tyler writes a Substack newsletter called The Operator about technology and business strategy. You can follow him on Twitter here.

“Should we rent or own?”

Three weeks ago my wife Jen and I hopped on a big steel bird to the Athens of the South: Nashville, Tennessee. Although I complete five years of surgical training at Stanford in June, I was lucky to be selected for a one-year fellowship in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at Vanderbilt Hospital. Hot chicken, live music, and a world-class facility — what’s not to like?

We had this lofty idea to buy a Nashville home and rent it out after the year — our first single family rental. While this was probably naïve, after burning hundreds of thousands of dollars on inconceivable Bay Area rent, we were jonesing for some equity.

So, armed with a dozen Zillow listings, a rental car, and American-dream-optimism, we set out to find Our First Home.

Almost immediately we felt the crushing weight of impossibility. Nothing was available, listings were outdated or just plain inaccurate, and when we did come across a property with promise, all-cash bidding wars meant we weren’t even in the conversation.

Since I graduated college in 2012 home prices have roughly doubled, meanwhile, the stock of affordable housing has dropped 30+%. And because I could never afford to buy, the many thousands of dollars I spent on rent never compounded, appreciated, or became a savings vehicle. Trapped in this vicious cycle and exhausted after hours of driving through every neighborhood in Nashville, Jen and I mutually resigned to the more manageable of two evils: another year of renting.

Mine is hardly an isolated incident. There are six million credit-worthy Americans who want to own a home but cannot due to affordability, inventory, competition or some combination thereof. But what if there was a third option — a financial instrument purpose-built to provide a real shot at homeownership?

Rather than rent or own, why not Divvy?

Founded in 2017 by Adena Hefets, Brian Ma and Nick Clark, Divvy offers a novel approach to homeownership.

Here’s the pitch:

A consumer selects the home of their dreams, which Divvy buys and rents back to them. A portion of every rent check is used to build consumer equity in the home, resulting in approximately 10% ownership after three years. At the three-year mark, the consumer may choose to buy the home from Divvy (using that 10% equity as a down payment) or cash out their savings.

Over the past four years Divvy has purchased thousands of homes on behalf of customers, and astonishingly one in two end up buying the home back from Divvy. Although Divvy is not active in Nashville (yet), it has operations in 16 major metropolitan markets across the U.S.

In fact, Divvy is now one of the top five acquirers of single family rentals (SFR’s) in America, competing with 800-pound silverback landlords. To bankroll this contest, Divvy is backed by a who’s who roster of venture capitalists and sports a private valuation north of $2 billion. There are even rumors of an IPO in the works.

This is a company you should keep both eyes on.

To better understand Divvy and the opportunity ahead, I sat down with co-founder and current CEO Adena Hefets. What follows is what I learned about her company — and her quest to improve the downright anachronistic instruments we use to make our largest financial transaction.

A Quick History of Mortgages

“If I go there will be trouble, an’ if I stay it will be double”

-The Clash

For almost a century, homebuyers have been wedged between two subpar options:

- Purchase with an all-cash offer, OR

- Finance with a mortgage

For most of us, this isn’t much of a choice. Unless you’re an oil baron or someone who dances really well on TikTok, you’re probably going to need to mortgage.

But mortgages are ancient financial instruments, composed of seven different fees, take 45 days to close, and are managed by multiple counterparties who each collect — and profit from — your data.

And mortgage math makes me queasy.

Here’s what the first three years of a 30-year mortgage looks like:

- First year, 78% of every monthly mortgage check is interest

- Second year, 76%

- Third year, 75%

So after 36 months of the majority of your paycheck going to a mortgage, congratulations! You’ve earned 2.5% equity in your home. And it will be another 13 years until your monthly mortgage check is more principal than interest.

This isn’t to say mortgages are inherently bad. For all their downsides, mortgages are generally a better investment than renting. What I am saying is that as consumers we deserve more choices, more innovation, more transparency in our financial transactions.

Fun fact: etymologically, “mortgage” means “death pledge.” While you might guess this implies one promises to pay until she dies, it actually refers to a Middle Age tradition of a pledge so solemn and vital, if broken, it dies. This pledge concept even makes a cameo in Shakespeare’s King Richard II (which I think we all remember).

While medieval by nature, the mortgage industry began in earnest in the 1940’s, and hasn’t changed much since. Following the Great Depression, homeownership rates in the U.S. were < 45%, and 10% of homes were in foreclosure.

In response, President Roosevelt instituted The New Deal, which included the founding of two organizations pertinent to our discussion:

- The Federal Housing Administration (FHA): Created national lending standards by extending insurance against default to lenders. Thus, the 30-year mortgage was born.

- Fannie Mae: AKA mortgage liquidity provider. Fannie Mae became the secondary market for FHA-insured loans, which could be sold as securities to the financial markets. This meant more capital for lenders to originate more loans.

The New Deal and its offspring generated a 20% rise in homeownership. Great success! More homeownership meant more citizens building wealth and paying more property taxes.

While homeownership rose above 60% by 1960, it remained at that level for the next thirty years. In an effort to push through this plateau, underwriting standards were dropped, and subprime lending commenced.

Again, great success! Not only did homeownership reach nearly 70%, but by 2007 you could get mortgages for multiple houses without even a steady job! That is, until these lending policies collapsed our economy and precipitated the Great Recession.

Amidst the fallout, underwriting requirements were significantly beefed up. In fact, average mortgage FICO scores went from 690 pre-recession to 740 post-recession, which effectively disqualifies 20% of the U.S. population for a home loan.

And the circumstances of 2021 made the mission of homeownership go from hard to impossible. Between record home price appreciation and the 30-year mortgage rate plowing through 5%, today’s average monthly mortgage payment is > 50% higher year over year. Meanwhile wages haven’t remotely kept up. When adjusting for inflation, wage growth was negative in 2021.

Still with me? There are two core takeaways from this sunny perspective:

- Mortgages are broken

- It’s never been harder to buy a home

I think this nicely sets the table for what’s ahead.

Founding Divvy

In 2017 Adena Hefets, Brian Ma and Nick Clark got together in Max Levchin’s startup studio, HVF, to found Divvy. I like to imagine the studio as a garage, but that’s not based on anything.

The team was laser-focused from the start on building an alternative to the traditional mortgage. They settled on a novel variant of the age-old rental model.

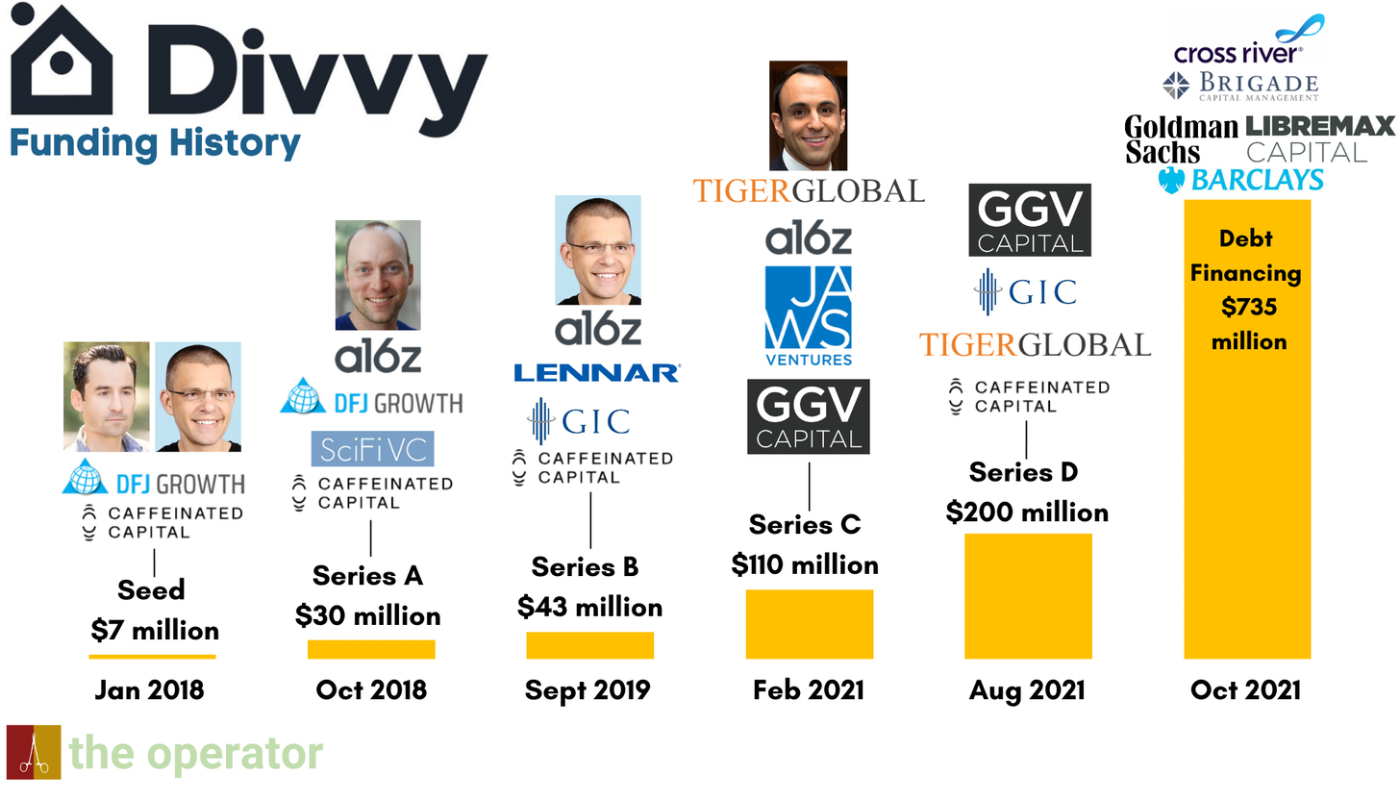

After a few months of building, the team was ready to buy houses. They raised a $7 million seed round from Caffeinated Capital, HVF and DFJ, and were off to the races.

Looking back, it was the perfect team for what Divvy set out to build, with sub-specialty expertise in real estate, capital markets and technology.

Although Brian Ma began as the company’s CEO, he moved to CPO prior to the Series A. The team quickly realized the meat and potatoes of Divvy was capital markets, and given Hefets’ history at TPG Capital, BAML and roles of PM and Capital Markets at Square Capital, it was mutually decided Hefets was the best fit for the CEO role.

With Hefets at the helm, Divvy proved out the initial model and raised an additional $30 million nine short months later. In the original pitch deck, the team highlighted the opportunity to create a new asset class of fractional homeownership using creative debt financing methods.

(I know this is a busy slide but I toiled over it)

Over the past 4 years the team has raised over $1.125 billion in debt and equity from notable backers such as Raymond Tonsing at Caffeinated Capital (who introduced me to Adena for this article 🙌), Alex Rampell at Andreessen Horowitz, and Scott Shleifer at Tiger Global.

As of the October 2021 debt raise, Divvy is now valued north of $2 billion, which makes it one of the most valuable private proptech companies on the planet — and in only four years.

This brings us to the obvious question (especially today) — how is Divvy’s solution so novel it warrants such a valuation?

A Novel Approach To Home Ownership

Here’s how Divvy works in five steps:

- Step 1: A customer applies for Divvy’s service and is prequalified for a cash budget in a few minutes.

- Step 2: With that budget, the customer shops for their dream home, using an agent of their choice or a Divvy agent.

(Note: This is a super-power of aligned incentives. Because home sellers — not home buyers — pay agent fees, it doesn’t cost Divvy anything to work with agents. Agents love Divvy, because Divvy makes their customers’ offers more competitive (all-cash), resulting in faster closing and commissions. Meanwhile customers benefit from all-cash offers, faster closing, and a realtor to guide them through the process. It’s no wonder Divvy today is partnered with 36k+ realtors. Win-win-win.)

- Step 3: Divvy purchases the home, including closing, taxes and insurance. The customer makes a down payment of 1-2%, which reflects their starting equity in the property.

- Step 4: The customer moves in and begins renting the home. A portion of each monthly rent check is deposited into a synthetic equity account, which is the customer’s ownership position.

- Step 5: After 3 years, the customer can either buy the home from Divvy using the 10% equity as a down payment, walk away with the savings, or continue renting.

Let’s double tap Steps 4 and 5, as these are the most nuanced.

Divvy’s monthly fee to the customer is composed of two portions: rent and equity.

- Rent: 70-75% of a customer’s monthly payment is what would be considered “reasonable rent” for a given home’s value (0.7 - 1.0% home value per month).

- Equity: 25-30% is used to grow the customer’s equity position.

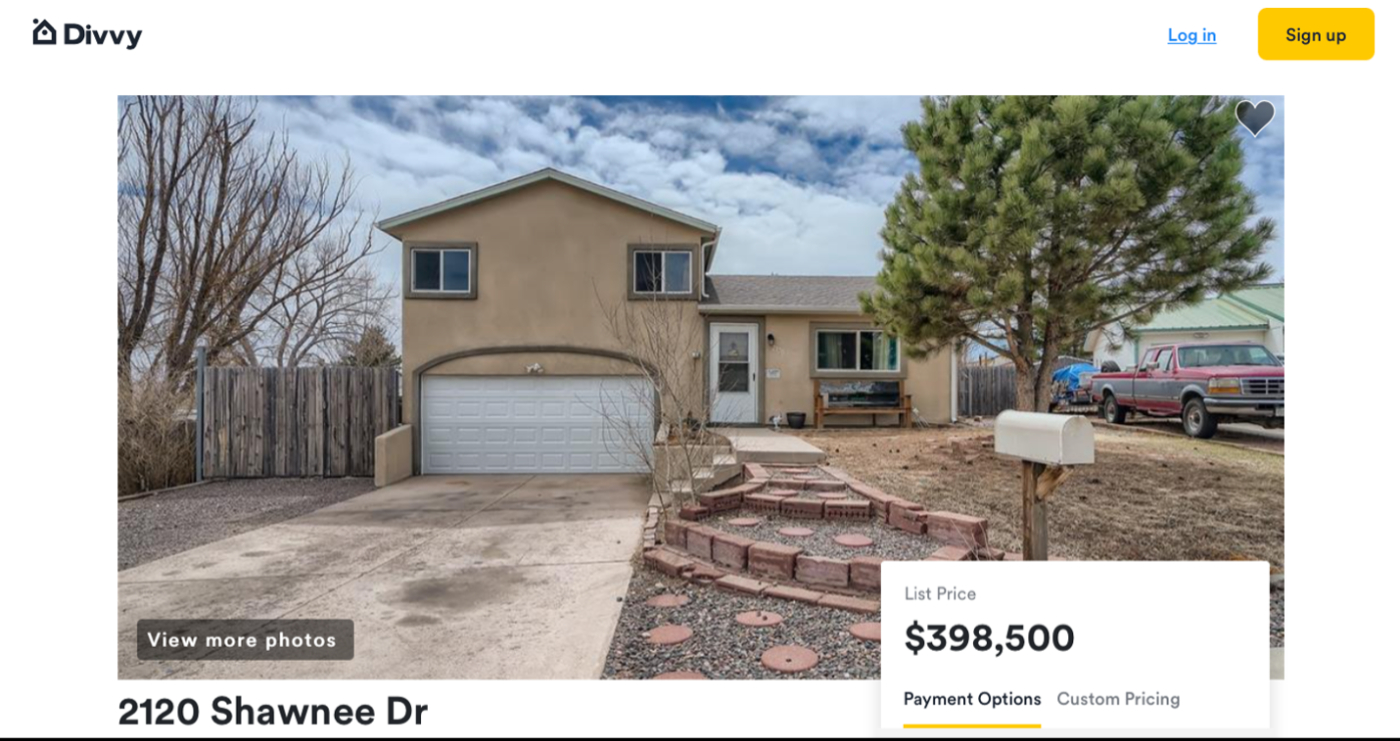

For example, the below Colorado Springs house is currently listed for $398,500.

Following a down payment of $8,000 (2%), the rental price to the customer would be $3,355/month. Of that check, $2,350 (70%) would be rent and $1,005 (30%) to build equity. Divvy manages property tax, HOA, insurance and major repairs/maintenance.

Additionally, an agreed upon “future” price of the home is included in Divvy’s initial contract, meant to accommodate three-year forward home price appreciation (HPA). Historically this has been a modest 3% increase each year (e.g., a $100k home at the end of three years would cost $110k to purchase).

Agreeing on a price three years in the future creates tremendous optionality for the customer. If the home appreciates more than the original agreement (see 2021), the customer is in the money — able to purchase the asset for less than it’s worth.

Conversely, if the home is worth less than the agreed upon price, the customer can cash out their savings and look for a different home (Note: if the customer does elect to cash out, Divvy subtracts a 2% fee to re-list the home and find a tenant).

Of course, there are downsides to this model. Renters end up paying materially higher rent than they would on equivalent properties to cover the equity portion. Additionally, because Divvy requires a 1-2% down payment (2-4X a security deposit), not all traditional renters will have the scratch to make it happen.

However, for those with savings that are willing to put more of their paychecks towards building equity, Divvy is an option worth looking into.

How To Win A Legacy Industry

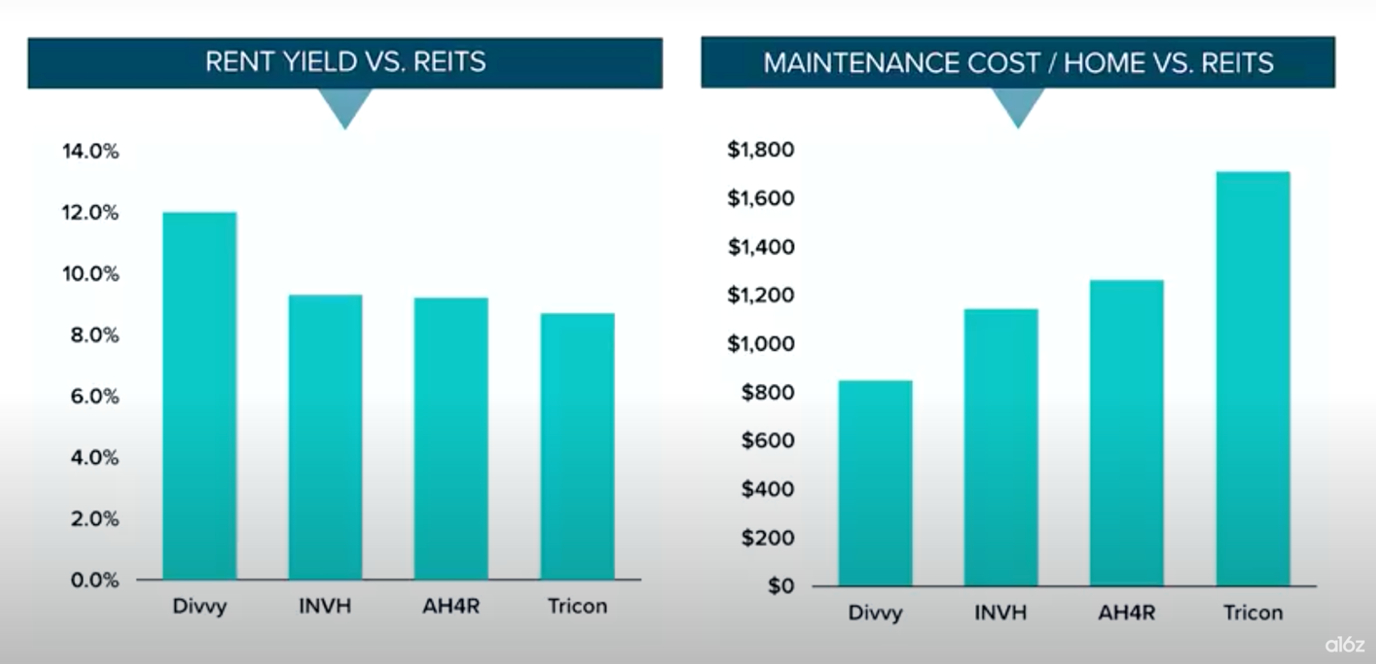

The colossal single family rental market is dominated by three powerful landlords: Invitation Homes, American Homes 4 Rent, and Tricon. These companies manage orders of magnitude more homes than Divvy and benefit from massive economies of scale.

So how does Divvy expect to take marketshare from such entrenched competitors?

Two ways: cohort editing and counter-positioning.

Cohort Editing

Read any fintech playbook and it will tell you to find an underserved cohort, provide an excellent customer experience, and use that as a wedge to move upmarket.

Divvy is not doing that.

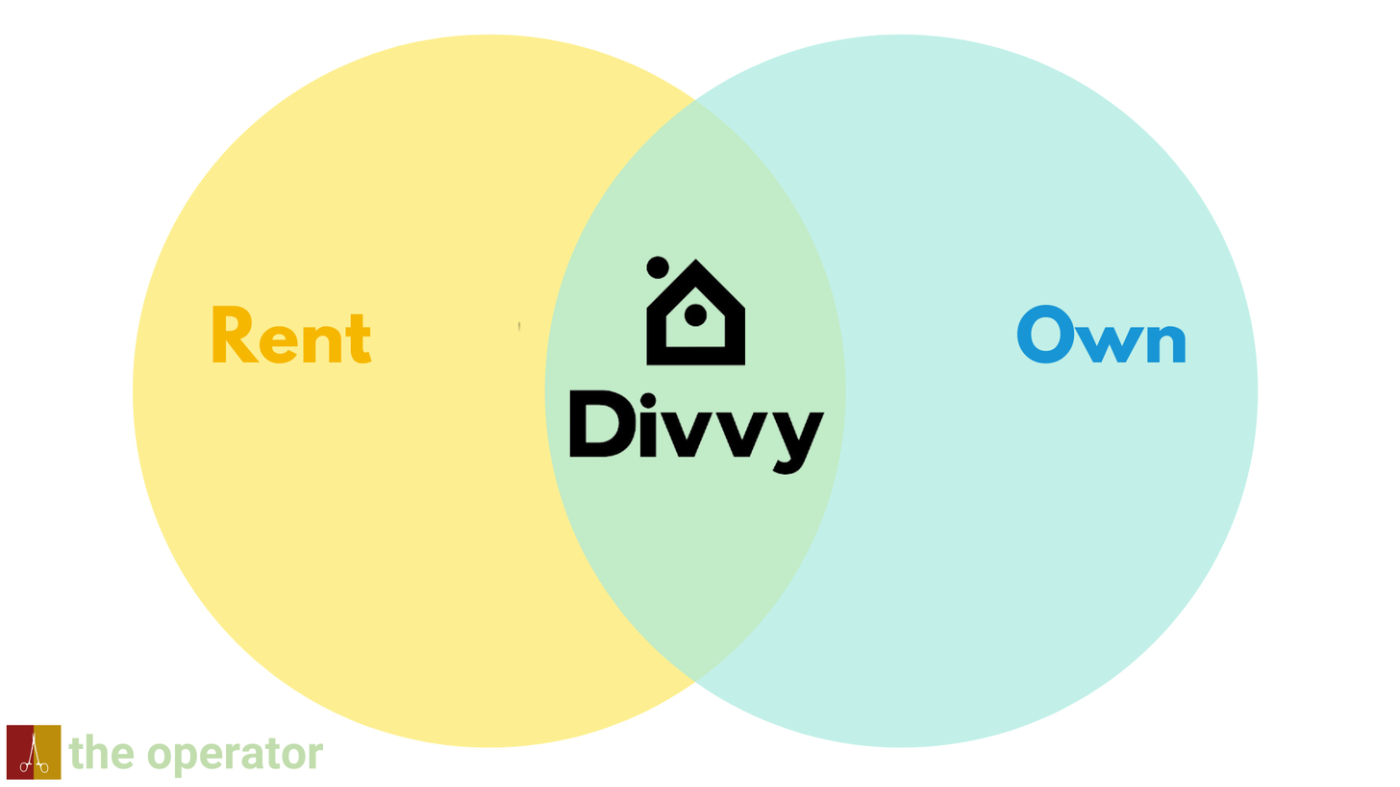

Instead, Divvy is creating an entirely new cohort of customers that neither rent nor own. They Divvy.

Of course, these customers must come from somewhere, which is the 45 million SFR tenants in America today. But because Divvy’s solution is so paradigm-changing, it results in almost unrecognizable consumer behavior and characteristics compared to the traditional tenant profile.

While renting and owning are two home transactions in parallel, Divvy runs perpendicular to both — a bridge between — an on-ramp to homeownership.

Better yet, by Venn-Diagram:

For starters, Divvy customers are more fiscally responsible than the traditional rental cohort. By requiring a 1-2% down payment, Divvy customers are pre-selected to be those with savings. And by allowing customers to both select the home of their choice, and become a partner in that home’s ownership, Divvy is betting the customer will take better care of the home. This means regular maintenance, landscaping, renovations, painting and any other investments you would never see a tenant make.

In the words of Warren Buffet, “Nobody washes a rental car.”

Counter-Positioning

One of my favorite business strategy books is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. In it, Helmer describes the seven moats a business may deploy to engender persistent differential returns. I wrote about the Seven last year in Palantir: On Building A Dynasty.

Divvy’s business model makes use of the classic upstart disruptive moat: counter-positioning:

Counter-positioning is when a newcomer adopts a novel, superior business model that the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to its existing business.

Invitation Homes’ business model has thrived by purchasing low-price or distressed single family rentals (the company purchased 48,000 homes between 2012 - 2016), sitting on inventory as it appreciates, and collecting income. There’s no material incentive for INVH to make tenants owners, or to share home price appreciation.

But that’s exactly what Divvy does, and it fuels the flywheel. By sharing home appreciation, Divvy tenants are more likely to become Divvy homeowners. In fact, roughly 1 in 2 Divvy customers end up buying the home from Divvy, which is 10X the next closest competitor.

Furthermore, because Divvy allows customers to select their choice home, the quality of Divvy’s inventory is higher than incumbents. Divvy’s customers are selecting from “for sale” stock, not “for rent,” the latter of which is always more poorly treated.

Do you remember your college dorm, or your first apartment? If it was anything like mine, the starting condition was bad and it got worse. This manifests as higher overhead — maintenance, repairs and replacement appliances.

Tricon doesn’t want to sell inventory because the result is lower monthly income and fewer tenants in the market. Divvy has created a model incumbents cannot copy or challenge without cannibalizing their own cashflows.

For Divvy, not only does selling inventory mean proof-of-model, increased home ownership and financially secure customers, it also creates ancillary fintech opportunities.

The Bull Case: Divvy’s Opportunity

Brief aside — if you’ve read The Operator before or are even vaguely aware of me on Twitter, you likely know I am an inner-circle Opendoor bull. While there are dozens of reasons to get excited about proptech investments, I ground my Opendoor thesis in two core beliefs, both of which pertain to Divvy.

1.) Hold the CAC, Please: The traditional real estate transaction involves upwards of six offline counterparties, each of whom charges its own customer acquisition cost. This means the customer is paying CAC 6+ times. If one company could internalize each of these services (home sale, mortgage, title and escrow, homeowner’s insurance, warranty), the home transaction could be ostensibly cheaper, more transparent, and more enjoyable.

This is the sweet spot in consumer finance for me — the Great White Buffalo, if you will. A solution so good that both patron and purveyor extract more value than the traditional offering. This is incredibly hard to do, and requires vertical integration, but those who can figure it out end up building huge businesses.

I find myself increasingly drawn to the impact of these types of investments. If you decrease the cost and friction of a transaction, more people can participate in that transaction. And in residential real estate, participation means wealth creation.

Shouldn’t that be the goal?

2.) Owning the Transaction: While every proptech company and their mother is gunning for the “super-app” ecosystem model, I believe only a specific flavor of company can pull it off. In particular, the company must own the very first step of the transaction, which is the customer buying the home.

If you begin with any service downstream of the transaction, swimming upstream to attach incremental services will be tough going. For example, if you are a title and escrow company like Doma, by the time a consumer arrives at your funnel they’ve already purchased the home, qualified for a mortgage, and perhaps they’ve even found a homeowner’s insurance provider.

Companies like Flyhomes, Orchard, Knock and Opendoor each offer products that grant homebuyers superpowers. All-cash offers, trade-ins and rapid closing means these companies own the transaction and can leverage consumer proximity to cross-sell ancillary services like mortgage. That’s why these companies have an inherent model advantage over Doma, Hippo, Better and even Zillow.

But Divvy is perhaps in the most advantaged position of all.

Companies like Flyhomes and Opendoor see a customer once a decade. But Divvy collaborates with its customers on a monthly basis for years. And if the customer desires to purchase the home, Divvy is the principle. No brokerage or agent fees.

As a trusted partner with a multi-year customer relationship, there may be no other company with Divvy’s leverage to cross-sell the entire transaction stack.

While Divvy does not offer ancillary services beyond buying and renting today, Hefets assures me it’s in the pipeline. Not just mortgage, but all of the above.

And that’s just the home transaction. Longer term, Divvy also has the opportunity to broaden offerings to tenants, such as renters insurance, landscaping, moving and internet/cable.

Let’s bring this all home.

Divvy’s bull case is that its lifetime value (LTV) to CAC ratio has the potential to be higher than any other company in proptech — and still offer more value to the customer.

Divvy in a Down Market

Although founded in 2017, Divvy’s coming out party — it’s Bat Mitzvah — was in 2021. A confluence of barebones home inventory, bantam-weight mortgage rates and bananas home price appreciation resulted in the hottest seller’s market we’ve ever seen. Would-be buyers like me were boxed out by competition, particularly in markets where buy-side fintech solutions don’t yet exist.

These events prompted customers to flock to Divvy’s platform, and Hefets reports the company purchased more homes in 2021 than the four preceding years combined. This makes sense — Divvy’s product-market-fit shines most brilliantly where homebuyer’s needs are greatest.

But what happens when these conditions reverse? What happens in a down market? I asked Hefets this very question. As a company holding billions of dollars worth of homes on the balance sheet, you have to wonder how Divvy would hold up in a recessionary environment.

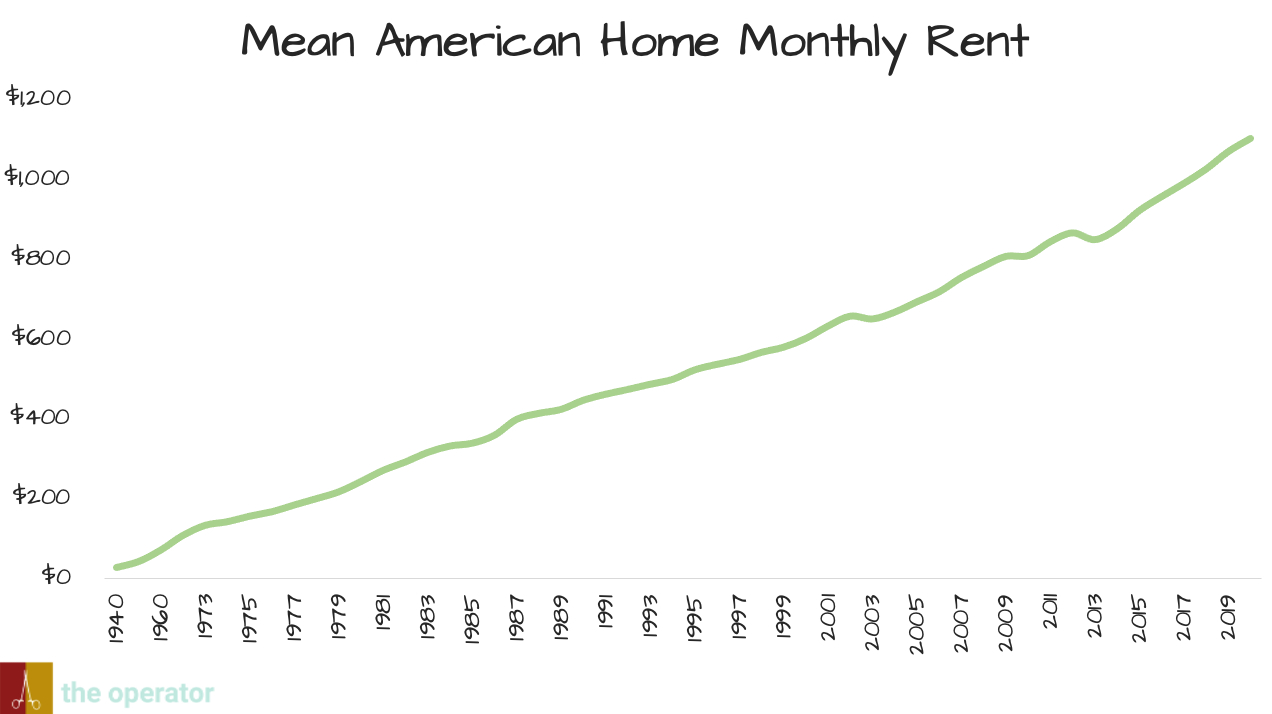

She taught me something I didn’t know – that rent prices are even more resilient than home prices. This was her response:

“The nice thing about this is that rent doesn’t actually decrease. If you Google rents going back 100 years, rents generally always increase. And in fact it’s generally counter-cyclical. Because during a recession it’s actually harder to get a mortgage, people flock to rentals, demand drives up and usually rents go up quite a bit.

So when we buy a house, for $100,000 and for easy math, call rent $1,000 dollars, that’s a 12% yield on rent, and that doesn't change. Even if the house goes down to $80,000, and my cost basis is $100,000, so long as I can keep renting the house for $1,000 a month, it doesn’t change. In fact we are quite risk mitigated because the yields are pretty steady and rents don’t decline.”

Admittedly dubious, I did exactly what Hefets told me to do and googled rent prices going back eighty years. The consistency of this slope shocked me.

Hefets was right. Even in recessionary years, it appears rent prices continued to trend higher.

Divvy’s model benefits from two cash-flow cushions that protect against dislocations: monthly rent income and customer equity. Rent is contractual and doesn’t fluctuate regardless of the housing market, which means steady, predictable, annuity-like income. Similarly, because the Divvy customer has equity savings locked up in the home, payment delinquency and/or lease breaking is strongly disincentivized.

These cushions have allowed Divvy to be flexible even in the face of unforeseeable events, such as COVID-19. In a company blog post, during the pandemic Divvy offered 100% of customers rent relief options, including flexible payments, no late fees, temporary suspension of savings portion of the monthly payment, and/or using a portion of home savings to pay rent. A testament to the financial profile of Divvy’s customers, only 28% required waived late fees.

As a final note, given our conversation around the risks of messing with mortgages, and in the context of the current volatile real estate market, it’s worth discussing whether Divvy’s model introduces excess risk. In fact, Hefets is often asked “Is Divvy the new Subprime?”

True to form, Hefets is quick to reply that 50% of the U.S. population is considered “subprime,” and that those individuals deserve housing options too. But also she emphasizes that Divvy’s model involves none of the risky lending that torpedoed our housing market back then.

“Now, the difference between Divvy and what happened during the GFC is, during the GFC you were extended debt. You were given credit; a mortgage. Divvy is very different. There is no debt. I’m not lending you anything. You are a pure renter in the home — which is what you would have been if you weren’t owning anyways.

Right? You’re an owner or you’re a renter. It’s one or the other. And you’re just buying into the equity of the property. That’s pure savings. That’s not debt.”

- Adena Hefets

There is no risky credit component to Divvy’s model. Rather, Divvy is providing a for-savings mechanism in an asset that compounds and appreciates over time. This is similar to putting money into a 401k, or the S&P 500.

The biggest difference is you can actually live in your Divvy house.

Closing Thoughts

In the 1970’s, an Israeli man found himself driving along the arid, northernmost tip of the Red Sea, near Eilat, Israel, when he saw a woman hitchhiking on the side of the road. He stopped and offered her a ride, surprised to find she was American.

They fell in love, she became pregnant, and they traveled to America to begin a life together. Soon after arriving, they began to search for their first home. And they found one — it was perfect. But without credit history and unclear earnings potential, they were unable to get approved for a mortgage. It turned out the American Dream was just that. A dream.

But the woman who lived in that home recognized the couple’s need and offered them a novel solution — seller financing. Rather than a loan, the couple could pay her in regular installments. They happily agreed, moved in, and in that house they raised four children.

To that family, the house was not just shelter; it was a savings vehicle. Through the equity they built they were able to live a comfortable life and send their children to college.

One of their daughters was particularly talented. She went on to attend Cornell, and afterwards landed impressive positions at TPG and Square Capital. She was able to use her family’s story — the kindness of a stranger who shared the opportunity of homeownership — to found Divvy Homes. She is Adena Hefets.

I love the sense of meaning the name Divvy imparts. Divvy means to share, to distribute, to allocate an even portion. Like healthcare, free speech, and personal security, I believe each of us has an inherent right to own a home. But that right is increasingly challenged, especially today.

Divvy has seen tremendous early success precisely because it confronts these challenges. I’m a believer.

As always,

Stay Convicted.

Tyler

By day, Tyler Okland is a head and neck surgeon at Stanford Hospital. By night, Tyler writes a Substack newsletter called The Operator about technology and business strategy. You can follow him on Twitter here.

If you liked this post, leave feedback below!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Tyler, is it not these companies that are responsible for low supply? They have capital to buy real estate, which they turn around and lease to prospective home buyers.

@nick.deshpande No, the primary cause of low supply is under building. We build the lowest number of homes in the past decade since the 1960's.

Divvy has purchased perhaps 3-4k homes. This is a drop in the bucket (6.9 mil home sales in 2021)