Kate here. When I worked at Medium, we shared office space in New York with a couple of other companies. Amanda Peyton was the founder and CEO of one of them (Grand St., an e-commerce site for tech hardware, which she sold to Etsy). A decade later, she had founded a consumer payments company, Braid, that didn’t work out. The story that she shares of Braid’s rise and fall is captivating, and the lessons she learned along the way are valuable for any founder, whether in fintech or not.

On the day I chose to start writing this, I went to an afternoon showing of Oldboy at the Alamo in Brooklyn. In the movie, there’s a quote that’s repeated at least three times:

Laugh, and the world laughs with you;

Weep, and you weep alone;

I’d been trying to write a pithy summary of my last four years with Braid, my consumer payments company. And here it was, served up on a giant screen.

Braid was around from 2019 to 2023. We designed and shipped a brand-new multi-user financial account called a money pool, and raised $10 million in venture capital from investors that I’d looked up to for years. It took us about two and a half years to find product-market fit, after which we grew sustainably and quickly. We’d made software that people seemed to want.

A few months later, we were dead.

The thrash happened fast and left a sea of heartbroken customers, employees, investors, and partners. The thing that broke us wasn’t a stronger blow than any of the others we’d experienced. It was simply the last one we could tolerate. The company shut down in September 2023.

That’s not the end of it, though. We ran an auction for our IP and there was a single bidder: me. You see, I believe that fintech is far from over.

Tolstoy was right: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” In my world, successful companies are all alike; every failed company fails in its own way. Failure is a cocktail of loneliness, grief, and shame, which is why these stories are not told often. But every failure is also a playbook for the next obvious success.

That’s why it’s critical to share these stories. I hope ours is helpful.

Braid’s empty office on Harrison Street in San Francisco.

Braid's timeline—and the myths I learned along the way

The road to product-market fit is littered with fraud, 2019-2021

Myth: Your early adopters are your best customers

The most concise explanation of the multi-user opportunity that we understood at Braid is this: there are financial accounts for one and two consumers, and there are financial accounts for businesses. But there is no financial account for n consumers. Joint accounts are outdated, often (but not always) capped at two, and not a product priority for most banks. A money pool could serve a customer base for which there was no existing product, only clunky workarounds.

We had an initial concept for the money pool right away. We had very few competitors, because multi-user bank accounts are difficult to build and operationalize, for reasons including limitations on what our banking partners could offer, a maze of compliance requirements, and UX challenges in introducing customers to a new banking innovation.

We iterated constantly for two and a half years. But there’s nothing like a hot market. In early 2019, neobanks like Revolut, Monzo, and N26 were taking over Europe. In the U.S., Stripe, Coinbase, Robinhood, and Chime were ripping. And we heard “yes” a lot in those years—from investors, customers, partners.

There are two types of product-market fit for a fintech company: fake PMF and real PMF. Many fintechs, including us, dupe themselves into thinking their PMF is real when it’s not. All the signs are there: enviable early traction, organic growth, and real payment volume. It’s easy to look at the numbers and say—wow, there’s real demand for what we’ve built. We’ve found our cohort of wildly passionate early adopters.

Unfortunately, we had fake PMF. We learned that a lot of our customers were criminals. They churned quickly when they got blocked. They comprised a high percentage of ACH returns, which we had to cover out of our own pockets. They had a high percentage of chargebacks.

You know who doesn’t move $500 into a brand-new app they’ve never heard of within 10 minutes of signing up? Real consumers. They need time to learn about the product, move $1 or $10 in and out, and make sure everything works.

They were early adopters because they were fraud sharks patrolling coastal waters for fresh meat. And our little payments app? Well, you can guess.

At first, fraud can feel all-consuming—because it is. We spent massive amounts of time on customer support, battling fraudulent customers who had complaints or wanted to take out frozen funds. We wrote software to combat fraud and incorporated anti-fraud thinking into every aspect of our business. I’m thankful that many great companies are working on this problem—we used Sardine, Sentilink, and Alloy. Others include Unit21 and Socure. Still, in the beginning, the fraud was crushing to handle.

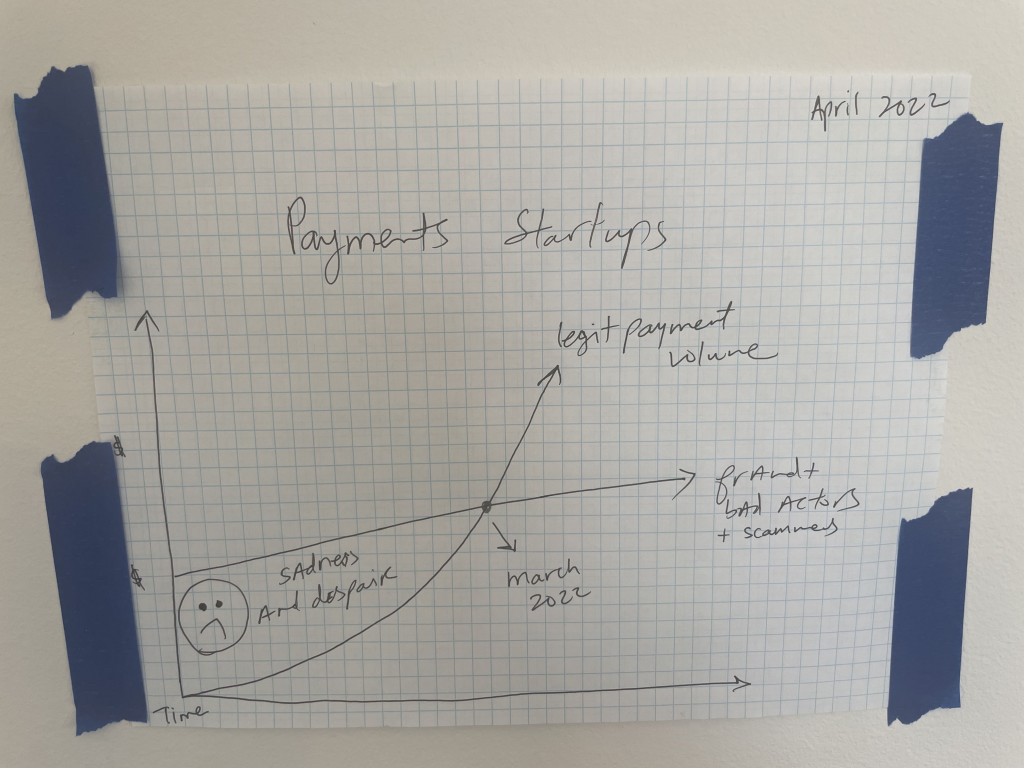

The bright side is that there are many more real consumers than there are fraudsters. If a product resonates, the ratio eventually flips. I drew this graph the day we figured this out, and it’s still up on my wall.

Then, it worked, October 2021-July 2022

Myth: You can always raise with great metrics

We finally found our groove in H1 2022. Our payment volume grew 5% a week, most weeks, for nearly 22 straight weeks. In five months, we went from processing less than $10,000 a day to having multiple $100,000-plus days. We were on track to pass $10 million in monthly volume by Q4 2022. We had figured out who our customers were, why they wanted what we’d built, and how to drop our user acquisition costs by inspiring customers to use Braid with friends and family.

We found myriad buckets of users who wanted multi-user bank accounts. A few examples from our data: co-parents, houses, art collectives, extended families who get along, teams, people who share livestock, churches, punk bands, weekend hustles, extended families who don’t get along, Wiccans, and our team’s personal favorite, firehouses.

The use cases that didn’t work well for us were short-duration social events, like group travel and bachelor parties. They had massive churn, relatively low volume, and little sustainable long-term value. Use Venmo!

I called one of our investors in early October 2021 to report what we’d figured out. He said, “Great, raise money immediately, the time is now.” This advice was correct. But I fought him.

I said, “If our numbers are great and consistent, we can always raise. Let’s wait it out a few more months.” I’d like to blame my foolhardiness on external factors—the long list of companies raising huge rounds off of zero traction, ZIRP, whatever. I’d been building software since my early twenties and felt that the rest of the world finally understood the magic of our business models.

But if I really take a hard look at that moment, it was about me and my ego. We’d processed eight figures of payments by that point. We grew consistently over the next few months. But venture capital is not for companies that are good, or even companies that are great. It’s for companies that are so excellent that they produce outsized returns at the right time, in the right market. We timed this wrong, and it hurt us.

I went to raise money in 2023, on the Monday before the Silicon Valley Bank crisis happened. There was less capital available for fintech startups and the environment was decidedly not in my favor.

Every dollar a startup can raise is a gift. For a time I lost sight of this, and I won’t make that mistake again.

The ice bath, July 2022

Myth: Ruthless dedication to compliance will save you from regulators

We’d finally found a delicate equilibrium with the many mouths we had to feed: consumers, banks, networks, regulators, employees, investors, vendors, and fraudsters.

But that balance got ripped apart when our partner bank’s behavior suddenly changed. For context, Braid relied on a handful of third-party partners to enable services like money movement. Building the technology ourselves would have required us to jump through regulatory hoops that were too expensive and time-consuming for a startup of our size.

On our own, we spent millions of dollars to build a best-in-class compliance program that sat alongside our offering. For every hour that we spent on engineering for a consumer-facing feature, we spent another hour on compliance, and a third on fraud. That meant everything took three times as long, but we didn’t see any other way.

What we didn’t understand is that even the most robust compliance program would only get us so far. We were taking on indirect risk from every fintech in our partner’s bank’s portfolio, as well as from our bank’s confidential relationship with its regulators. Fintechs sit adjacent to regulators—not directly under them. We’d hear mission-critical information through backchannel whispers and messy games of telephone.

In the summer of 2022, our partner bank stopped replying to emails and became noticeably cagey on phone calls. When they did reply, they would demand things they hadn’t asked us about in years. We’ve never heard the full story, but this bank isn’t in the fintech sponsorship business anymore—with us or with anyone. Eventually, we had to move to a new bank. We offboarded and cashed out all our customers in the summer of 2022.

It felt like a bucket of ice had been dumped over our heads. Here is a highly realistic AI-generated image of me at that moment:

In fintech, it’s easy to pit technologists and regulators against one another: fuck around on one side, find out on the other. But we knew it wasn’t that simple. Our product did not belong to any legal gray areas (like crypto). It fits within the bounds of existing law. Yet if the regulators come down on your partner bank for their relationships with other customers, there’s nothing you can do about it. A regulatory rug pull can outstrip any early traction or compliance gold stars.

As a startup, we were a tiny rivulet downstream of the ocean that is the U.S. financial system. When the dam broke, we learned quickly that no one cared about our perfect BSA—Bank Secrecy Act—audit.

As a result, my feelings about how to build fintech software have changed drastically. Initially, we thought leveraging third party software would help us move faster and focus on our core offering.

Instead, what we found was that every additional partner had the potential to break big, important parts of our stack. By the end, if there was something we could build ourselves in Retool, we did.

In addition, building mostly in-house was the only way our unit economics worked. There’s a lot of great fintech software, but if it eats your entire margin, you’ll end up dead.

We’re so done, we’re so back, we’re so done, July 2022 – April 2023

Myth: The answer is AWS for fintech

The company was effectively in a coma from July 2022 to January 2023. Without our partner bank, we couldn’t move money. It was bleak—we were a payments company processing $0 in payment volume. Eventually, we found a new partner bank that wanted to work with us. We spent six months on the migration and Braid came roaring back to life in January 2023.

We started from zero and processed over $1 million in the first 30 days of our relaunch. It felt like we’d quickly get back to where we left off. In spring 2023, we signed a term sheet for a new round of funding—although it was not as easy as it would have been in 2021.

The euphoria did not last.

Six weeks after our relaunch, SVB imploded. Right after, Hindenburg Research’s Cash App report dropped, resounding a damning bell for the reputation of fintech startups everywhere. The market worsened. Interest rates kept going up.

The nail in the coffin came soon after. A critical third-party informed us that they’d changed their mind on a key technical decision. This change was going to break all of our software. We had two decisions: rebuild from zero or shut it all down. It didn’t feel right to take additional capital knowing this, so we called off the round.

Once we decided it was over, I spent the morning sitting in my Herman Miller chair that would soon be sold, zooming from one end of the office to the other. Could I put it off, just one more hour? The dread and loneliness I felt is hard to overstate—sending out final emails to customers, laying people off, selling everything, and telling our investors.

I’ve been lucky to have started four software companies. Whether they end in a “good outcome” or “bad outcome,” it’s devastating.

Shutting down, IP sale, June-September 2023

Myth: Failure is a learning experience for everyone

The team was gone by June. I spent the summer winding everything down. The first note I wrote after we shut down said: when you win, you win together, and when you fail you fail alone. For everyone else, our failure felt like a lesson, a “case study.” For me, it was a punch in the gut. In my opinion, the best quote on failure is from Rippling’s Parker Conrad:

‘Failure is really, really, really awful…People describe it as, ‘Oh, you learn so much from failure.’ I don’t think that’s true. I think the only thing I learned was how much failure sucks and how soul destroying it is.’

It was important to write these lessons for others to learn from. But the biggest takeaway for me was that I never ever wanted to fail again.

Braid shut down almost three years after we wrote about why we think multiplayer fintech matters. To this day I believe everything I wrote—the soul of the product didn’t change much over the years that we worked on it. We swapped features, changed banks, and processed thousands, then millions, then tens of millions of dollars.

We ran an auction for the IP. In the end, there was only one bidder: me. This happens more often than people realize—there are very few bidders for software on its own. Payments software has enormous compliance, fraud, and regulatory overhead, and has little inherent value. All our major investors approved of the sale, and I’m grateful that they did. Braid’s second act is currently a Substack email list (sign up!), a GitHub repo, and a blinking cursor in a brand new Google Doc.

Will it be different next time? Yes. Absolutely. So much has changed about the product vision, market conditions, and business model. Every startup is an amalgamation of thousands of data points that are changing in real time, and no two companies are the same. The throughline is making something people want. This will never be a myth.

I’m sure that Braid’s second act will be just as tumultuous. Consumer financial needs change faster than our financial system can evolve to meet them. This is a fact. There’s an enormous opportunity to build excellent software that solves a tangible problem, and that’s why I keep going.

And I hate to lose.

Amanda Peyton was most recently the founder of Braid, a consumer payments company. Previously, she was the founder and CEO of Grand St., acquired by Etsy in 2014. She has worked at Google's Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP) lab and attended MIT Sloan and Y Combinator, and was named one of Fast Company’s “100 Most Creative People in Business.” This piece was originally published on her website.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

The decision-making through the course of the story is interesting. The events show how much is outside a founder's control. I love the term "fake PMF"!!

Thanks for your vulnerability

Great story, thank you.

I work in fintech startup for the last 7 years, what I learned is that for every critical third-party dependency you need at least two independent vendor integrations that you can substitute in relatively short period of time. This gives you leverage for pricing and safety in a case of one them goes down / changes offering or 10s other reasons that could result in broken relationship. It could apply to payment gateways, communication providers (sms, email, notifications), fraud detection, verification services, etc. It's annoying to build the same thing multiple times, but it's better than being on a verge of shutting parts of the system down and loosing customers.

Really appreciate this

A quite fascinating journey you had there Amanda. Loved the quotes you slipped in there. All the best for your new venture.

To really know failure, you have to lose your house (all of them) along with every penny you own. Then you'll never fail again.

Thank you for this transparency.

Having worked in FinTech, I understand and identify with a lot of this. As a 25-year serial startup employee, not a founder, I also hate losing... and I was part of one that fell apart, despite healthy raises and PMF indicators. I always thought there was a way through it—by making one of our partners the hero, not ourselves—but we didn't take that path. Would we have survived if we had?

There's no such thing as a sure thing with consumer fintech innovation.

Best of learning and breakthroughs in your next venture!