Sponsored By: Fraction

This essay is brought to you by Fraction. The best developers already have jobs, so why not work with them fractionally? If you are looking to scale your startup without breaking the bank, Fraction is here to help. We connect you with fully vetted, US-based senior developers at a fraction of the cost.

Last week, Omegle shut down. Founder Leif K-Brooks marked the death with an impassioned letter posted on the shuttered domain: the stranger-matching site and teenage cultural cornerstone, which launched in 2009, was no longer financially sustainable to run.

Omegle influenced some of my early beliefs about the internet—namely, that it is a boon to meet and empathize with strangers from different places, and that in understanding others, we can better understand ourselves.

In conversations on Omegle, I found new music and vented about relationships, swiping quickly past screens focused on crotches in search of connection. Once, seated with my friends around a college dorm room table, I listened to a teenage girl talk about an abusive relationship she was in. It made us cry. When she dropped the call and Omegle sent us away to another stranger, we realized that we would never know if her story was true—that Omegle was often a fiction.

Not just a fiction, but a rollercoaster of surprises and horrors. You never knew what you were going to get, but it often involved unwanted nudity. These pernicious forces were what ultimately came to define Omegle, and what eventually brought its downfall.

In 2021, a young woman sued the website for failing to protect its users, seeking $22 million in civil damages. When she was 11, the girl met a man on the website, who moved the conversation to messenger app Kik. From there, he proceeded to coerce the girl into unwilling sexual acts. Omegle settled the lawsuit off court for an undisclosed sum days before founder Leif K-Brooks shut it down.

Scale Your Startup with Experienced Fractional Developers

With Fraction, you can tap into a pool of fully vetted US-based senior developers at a fraction of the cost. We bring you the best talent without breaking the bank.

Our developers are MIT-vetted and experienced in AI and LLM. They're ready to help your business grow, whether you need assistance with coding, software development, or project management.

Forget offshore outsourcing - work with top-notch developers right here in the US. With Fraction, you can accelerate your startup's growth and stay ahead of the competition.

Ready to take your startup to new heights?

I stopped visiting the site as I grew older. My habits centralized to a few, large, well-lit corners of social media. Still, this poorly designed, poorly moderated site managed to remain popular, experiencing another surge in activity during the onset of Covid-19. A new generation spilled into its virtual seats, and guitarists, singers, and other creators became famous recording scenes from their encounters on Omegle. Omegle had 58 million visitors in September 2023, according to SimilarWeb, and less than a quarter of those users were from the U.S.

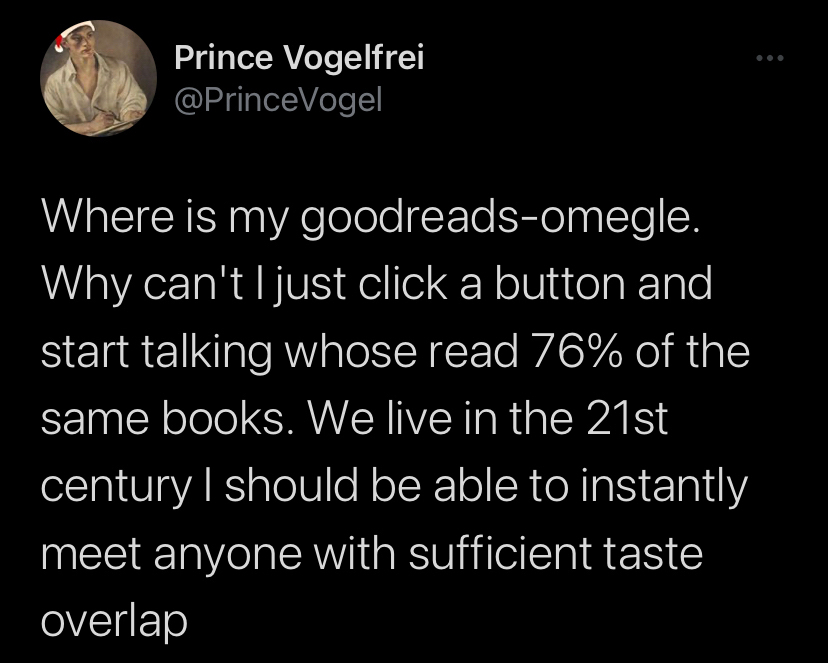

I don’t know how to mourn Omegle. How do you mourn something that was never quite what it set out to be? It is my belief that despite the site’s crass—and even dangerous—reputation, it addressed an unmet need. I still believe that it’s important to connect with strangers online, that there is beauty in sharing things with new people, and in finding common ground with people we assume are nothing like us. But Omegle never managed to pull that off successfully. And that made its death inevitable.

Leif K-Brooks was 18 years old and living with his parents in Vermont when he started Omegle. In his letter announcing the site’s demise, he detailed his own experience with sexual assault and the sense of security that the internet provided him relative to the physical world. He acknowledged that the site has been used for many things—to connect, yes, but also to commit “unspeakably heinous crimes.”

K-Brooks, who currently runs product recommendation startup Octane.AI full-time, also wrote about Omegle’s attempts at content moderation. It used “state-of-the-art AI operating in concert with wonderful human moderators.” Still, none of these methods were enough. Although the company’s methods grew sophisticated enough to track potentially hundreds of thousands of sexual assault incidents targeting minors each year, it couldn’t stymie the flood of harm on the site.

In the 2021 lawsuit, Omegle was accused of product liability, meaning that the site lacked proper warnings for what would happen once a user hit “start.” At the time it shut down, the site had only posted a warning that users needed to be 18, or 13 with parental permission, to use it. There was no requirement to certify parental consent or enter birthdates.

And yet, it’s important to keep in mind that Omegle is not the only place on the internet plagued by bad content. Nearly all of the internet is. This is where Section 230 comes in. The law, passed in 1996, absolves platforms of content posted by users, with certain exceptions including child pornography and copyright violations. All moderation outside of that is what makes a platform usable and sustainable in the long run.

But content moderation is costly work. Meta spent $5 billion on “safety and security” content moderation measures in 2022 alone, and signed a contract for at least $500 million per year with the consultancy Accenture for this purpose. Each year, Meta’s moderation engine finds more content to remove, and is presumably getting better; the number of posts removed with adult nudity and sexual activity increased from 38.6 million in the first quarter of 2023 to 51.2 million one quarter later.

Unfortunately, these are not achievable goals for smaller social media companies, let alone Omegle, whose primary source of income was display ads from those few companies willing to deal with its more unsavory aspects. It also offered a premium service offering an ad-free experience and customized profiles. Neither seems to have earned the website enough money to improve its offerings, and certainly not enough to maintain the delicate balance that K-Brooks aimed for—to both run live videos and match strangers, with no verification needed whatsoever. And what’s said and done on live video between strangers is more difficult to moderate than text, making Omegle’s responsibility a little more challenging than what your average social media company deals with.

Therein lies another question for K-Brooks, and for anyone who hopes to start a similar website. What are the ethics of leaving a site like Omegle running—with its popularity and dangerous corners—if you’re not going to turn it into something real?

In 2014, Omegle filed a law enforcement guide in Kentucky. It showed the limitations of Omegle’s attempts—the company agreed to moderate snapshots of videos at the start of sessions, and not during actual conversations, when most of the danger occurs. Despite long strides in artificial intelligence since 2014, the type of live moderation required to transform Omegle into a safe, well-oiled machine is still expensive to do at scale. And the magnitude of obscene content is so vast that scaling human moderators would be expensive—and potentially unethical for people to sift through.

We are about 20 years into the usable internet. We understand how to build things, and how to make people flock to them. Still, it seems that we have learned nothing from the past.

When we mourn the old internet—not just Omegle but Del.ici.ous, GeoCities, LiveJournal, AIM chat rooms, and various, functional forums—we must remember that we are not only mourning random dust-filled corners but also the way we once met strangers online. We mourn that we once believed that building tools to communicate better with each other—across classes, countries, devices—was a worthwhile pursuit.

Before Omegle came ChatRoulette, founded by 18-year-old Andrey Ternovskiy. In an interview with The New Yorker in 2010, Ternovskiy, a high school dropout from Moscow, says that he came up with the idea for the site while working at his father’s upscale souvenir shop, where he met people from “hundreds of different nations a day.” The following summer, he tried to recreate the feeling on the internet, and it took him three days to build a basic version. Without even trying, ChatRoulette went viral, laying the ground for Omegle’s success.

To grapple with Omegle’s legacy is to know that it failed its most vulnerable users. There are conflicting truths here, of harm and connection, of horrors and beauty. How do we allow ourselves to hold all of these different things in our minds?

I think again about the young girl in an abusive relationship whom I met with my college friends. I remember how moved I was, how we all felt closer afterwards. I think about the girl’s desire to lie and my desire to empathize with her. I’m not quite sure of the path forward, but it is hard to imagine an internet of the future without a platform like Omegle. It should—and can—exist again. But questions of monetization and content moderation will loom large, and will have to come first.

Meghna Rao is a writer and editor. She previously launched an editorial function for startup bank Mercury, was on the founding team of The Juggernaut, built research for CB Insights, and reported on tech out of Bangalore for Tech in Asia.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!