Sponsored By: Vanta

This essay is brought to you by Vanta, the leading Trust Management Platform. Need SOC-2 Type I? They can help you get it in just two weeks.

Good cogs get their performance reviews in on time. They never complain about company policy. They keep their trackers up to date and are always on time for meetings. Their managers never have to ask them twice about sending their weekly update, updating their deals in Salesforce, or closing out their Linear tasks. They’re more of the ask-for-permission than-forgiveness type and don’t give a darn about having an original idea so long as the OKR is green by end of quarter. They reach inbox zero every day, have an extensive LinkedIn bio (probably written in the third person), and love talking about Atomic Habits (although it’s entirely likely they only read the CliffsNotes).

Okay, I’m getting a bit carried away, but I find good cogs excruciating to work with. It irks me how they somehow find a way to meet all the criteria, yet never produce anything that’s actually good. They regurgitate things the company leaders say in a way that makes me uneasy. They attract the kinds of managers that business books call “B players,” who hire the “C players” that make everyone’s work life so mediocre you could scream.

Sometimes, I want to give these good cogs three knocks on the head and ask, “Is anybody home?!”

The truth is, I haven’t encountered many good cogs. I don’t think many people work at startups to work like cogs. I think people work at startups because they are ambitious, hungry, enthusiastic about challenging the status quo, and want to make real contributions to progress.

These types are similarly easy to spot because they say things like, “I understand others do it this way, but I still want to know why they do,” or, “Sure, that tiny thing is broken, but what if we’re onto something with the big idea,” or “Let’s give it one more rev, this time with some extra oomph.” They don’t have sharp elbows or point fingers, and they’re not trying to make a mess or get anyone fired. They just want to get it right more than they want to get it done. They take pride in their work. They’re alert, inquisitive, and push for things to be better. And they’re an absolute blast to work with because thinking and caring is infectious.

Do you need a SOC 2 ASAP?

Vanta, the leading Trust Management Platform, can help you get SOC 2 in two weeks. Get SOC 2 and close more deals, hit your revenue targets, and create a solid foundation for security best practices.

The promise of work environments full of people like this is deeply compelling. When Richard Feynman received a Nobel freakin’ Prize, this is what he said actually mattered: “The prize is the pleasure of finding a thing out, the kick in the discovery, the observation that other people use it—those are the real things.” These are the types we love working alongside in startup land.

I believe we all want those “real things” at work. We want to see the best we’ve got, day in and day out. We want to make our mark on this world.

It’s why startup leaders captivate us when they say things like, “Good ideas can come from anywhere,” and, “We value agency,” and, “Everyone’s an owner.” I majored in art history at a liberal arts school, and now I’m the founder of a venture-backed software company. The idea for Amazon Web Services started as a memo placed in the company suggestion box. Startup poster culture got going when a bunch of Facebook employees created an after-hours print studio. Post-It notes were born out of a product flop when its inventor accidentally created non-sticky glue. Our industry is built on the belief that anyone, anywhere can make a difference if we care enough, dream enough, and work hard enough.

But the realities of our day are not lining up with that vision. I fear our organizations have sold us a dream of autonomy, agency, and real connection to our work and our colleagues—but have set up conditions and tools that only good cogs would thrive in.

If I were a PM building tools for good cogs, I would create lots of little tasks to close and comments to resolve. I’d make confetti fly when someone finished a mundane task or cleared a queue. I’d produce a game of notification whack-a-mole that leaves players with an arm sore enough to proclaim a hard day’s work. I’d replace sending a colleague a genuine message of gratitude with a suite of silly emojis and cute icons to react with. Maybe I’d even offer a slick integration with ChatGPT so that no one ever has to write a performance review or product spec ever again.

If we want people that think, innovate, and pursue big things, why is this the way our collaboration tools actually work? And why aren’t we doing more about the havoc they are so clearly wreaking?

A product leader and thinker I admire, John Cutler, recently tweeted, “The tools used to tame messes, often reinforce messes.” Someone cheekily replied, “Conway’s Law: organizations design systems that mirror their communication structure.”

Our tools want to make good cogs of us. They’ll even say we were asking for it all along. But I honestly don’t think we intended it to be this way.

Take a look at these screenshots from Slack’s homepage over the years (courtesy of the Wayback Machine). Does this describe your experience using the tool today?

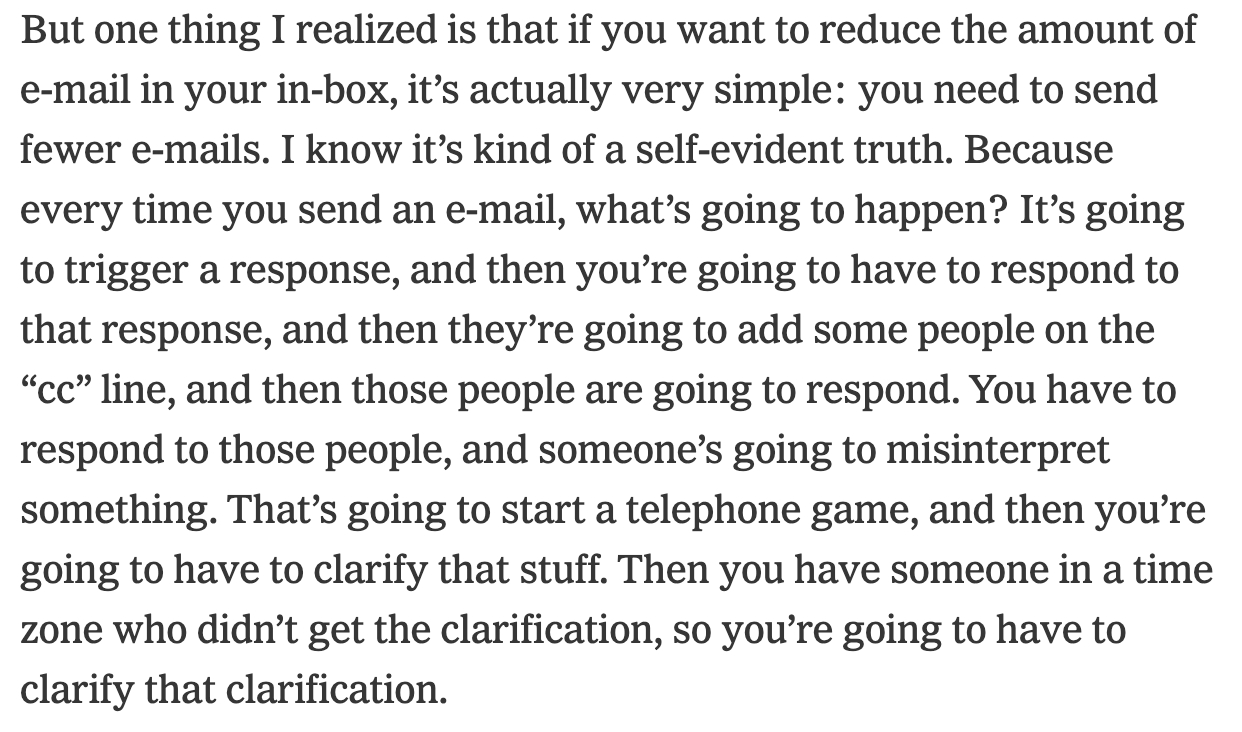

Someone recently described Notion to me as “where great docs go to die.” And here’s Jeff Weiner, former CEO of LinkedIn, on the mess one little email can make.

I don’t mean to throw shade at these objectively useful tools. There is certainly a place in organizations for this kind of communication, and we should, of course, lean on software to reduce monotony and drudgery in our work lives. Working friction-free is a salacious pitch to busy people. Multiplayer dynamics set PMs up for snazzy-looking DAU charts and founders up for peachy board meetings. But what do we lose when we work this way?

Never have I ever once sent a Slack message without editing it later for clarity or typos. I don’t feel the joy of collaboration when I’m resolving comments in a file or watching someone’s cursor move around my doc when I’m trying to think. Call me a Luddite, but I don’t see any dignity in creating or receiving a performance review written by GPT-3.

Sometimes I find myself in an infinite loop of checking all my inboxes and cannot stop for tens of minutes. Boy oh boy, do I get a dopamine rush when I reach inbox zero or close out all my tickets. The best part is, before I get a chance to ask myself if I actually got anything done, the inboxes and queues are full again. Brutal.

It seems like every time we get a tool that’s supposed to help us work better, faster, and smarter, it turns us into reactive, transactional, careless chaos monkeys. And with these tools so deeply ingrained in our workflows, have we built better, higher-performing organizations? Are employees more satisfied and productive?

We know when we’re making an impact at work. We can feel it. And this ain’t it.

I’m calling too much motion, not enough progress. Too many Slack exchanges, not enough retrospectives. Too much speed, not enough velocity. Too many inputs, not enough outcomes.

It’s time we rebuild the rhythms of our organizations around the substantive bits instead of the knee-jerk ones. What happened to virtues like discipline, contemplation, care, and reflection in our work lives?

Many of the founders I’ve been talking to lately report being happier after doing layoffs. They express relief in re-discovering simplicity and focus. They express joy in going deeper on fewer things. They describe a certain coziness at work again. There really was something to that two-pizza rule, after all. They can’t believe how chaotic it was before. I know that sounds scary for many of us thinking about the future of our careers, but I think there’s something to learn here.

If I were a betting woman, I would say that looking ahead, organizations are going to start re-prioritizing and celebrating deep thinking, focus, and connection as a critical feature of work again.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think the best work will be done with employees sitting at their desks with their head in the clouds all day. But I do think some of it should be expected for anyone that puts their hands to work on keyboards.

I am certainly biased, but I think we should be desperate for tools, norms, and processes that urge us to think, not just respond. Because that’s the place from which the enduring companies and careers will spring.

So, thinkers and tinkerers, wherever you are in your org—at the tippy top, in the messy middle, or in a random corner—I implore you to tell us what’s on your minds and in your docs. Let us know what you did and what you learned along the way. Think and care. Think and care a lot. Make your mark on your organizations. Your colleagues are waiting.

Brie Wolfson is the founder of Constellate, a home for your best work. Before that, she researched and wrote about company culture via The Kool-Aid Factory. She previously worked at Stripe (Biz Ops, Stripe Press) and Figma (Figma for Education).

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Oh man oh man. I felt that rant.

I think the worst of it all is how easy it is to get set in the coggy set of mind. Slowly lulled in a rut. Then it gets post-hoc rationalized - people will think that it's part of doing business and growing an org. That there is an inescapable reversal to the mean for any once glorious thing. And same for a product, not cared for enough your thin vision gets diluted until anything that's left is some lukewarm compromise that nobody likes. That's "crossing the chasm", "catering for new markets", or something to that effect.

That dropping of standards, the seemingly irreversible loss of a spirit, depresses me quite a bit. I'm allergic to wasted potential, efforts, and ideas; they make me mad more than anything. I remember being sad as a kid thinking about toys nobody cared about and how many people helped make them. I'm still there often.

There is another Cutler idea that I keep thinking about, people with both "sensibility to incoherence" and "willingness to fix it". I think like that too, in any org you'll always have people fight for better, more thoughtful work over the noise passing for the signal. People with the right level of agency. Just need to get enough of them around in the right position with the right support for magic.

I think it's why I'm addicted to startups, and small ones at that. You get to demonstrate that there is a better way and show undeniable results. With the added panache of beating orgs 100x the size and full of cogs. It's the positive affirmative way of being fed up with it. It doesn't get enough credit compared to the business model or tech innovations.

Thanks for the words Brie, very communicative enthusiasm as always.

Love that article.

First thing which came to my mind: Less writing and scheduling, more phoning and talking. Working in sales I learned that most of the issues/questions which often end up in our pipeline/slack channels etc. could have been solved with one easy phone call instead of another task or follow up message in any tool.